As commandos go, Abu Moses was about as nice a chap as one is likely to find. Absent was the preening narcissism of so many of his ilk -- the inevitable chip on the shoulder, the puerile, self-absorbed pout. No, whether by intention or by nature, Abu Moses defied the mold: forever, among his cohort, the homeboy, the trickster, the class clown.

In retrospect, it would indeed have been far easier to imagine him some first-generation immigrant's son making his way through a sweaty, small-town Iowa evening, Brylcreem'd bangs slicked back, double-booked between some freckle-faced drugstore girl and his buddies out front revving a mint-green Buick, angry to get someplace small time.

But it was not some backwater Midwestern ville where Abu Moses dwelt; it was the city of Belgrade in the mid-1980s. During that nominally socialist era of post-Titoist sloth, just before the storm. Before the present-day Crusades; before the Berlin Wall had fallen. Before war had ravaged the land.

At the time of Abu Moses' stay in the Yugoslav capital, Marshal Josef Broz Tito had been dead a numbing seven years. Nonetheless, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (still highly esteemed throughout the Third World as the progenitor of the Movement of Non-Aligned Nations) continued to host students from member states: fresh-faced youths from such far-flung climes as the People's Republic, Nepal, Cuba and Peru, Egypt, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, and both Iran and Iraq (then at war with each other and simultaneously supplied by Yugoslav tank and munitions factories in Skoplje and Kragujevac).

During this same era, the Republic also provided what was reportedly the most generous refuge of any East European nation to the Palestine Liberation Organization (under the strict caveat, of course, that no organization-related violence would occur on domestic soil). The terms of the PLO's guest residence had been negotiated between Abu Moses, his colleagues, and the Yugoslav chief of security over mandatory gifts of customs-restricted Johnnie Walker in the bowels of Belgrade's underground police headquarters and prison (where domestic dissidents languished), known as the Cave.

And indeed, that agreement was honored: During the PLO's entire Belgrade stay (with scores of youth on PLO scholarships, many from bitterly opposing factions) only one such incident occurred: In leafy Kalamegdan, an Ottoman Turkish fortress, now Belgrade's central park, when a rank-and-file Fatah member stabbed a low-level recruit from Ahmed Jibril's PFLP-General Command. Word had it that the incident was personal, rather than political, in nature.

Though Abu Moses' given name was Ibrahim, his colleagues all called him by his nom de guerre, with its curiously comic ring: "Abu," though he had no child of his own and therefore was not, at least in civilian terms, truly entitled to a filionym, and "Moses" (rather than the Arabic "Musa"), pronounced in gum-snapping American; a name that, while not uncommon among Arab newborns, was bequeathed far more iconically to Jewish ones. The result was a slightly clownish moniker eliciting fond hilarity every time it was uttered.

"Abu Moses! Abu Moses!" his cohort would hoot affectionately at welcoming ceremonies for touring PLO dignitaries, from whom the young operatives were cordoned off on the sidelines, like stock, behind crimson velvet ribbons. Here, at the margins of the action, discipline waned, and the leather-shod PLO scholars would once again transform into village boys, with village boys' ruthless compulsion for scorching nicknames.

Why was the man called Abu Moses? Last century's end has come and gone and that small mystery was never revealed. Perhaps to commemorate the prophet of the three faiths or, more likely, some fallen comrade. Or perhaps it was a mere product of the times: the twilight years of the 1980s, when insidious, prefabricated pop music -- either American-made or a direct imitation of it -- had begun to metastasize in promising young minds from purist Scandinavia to the most obscure regions of the former Ottoman Empire.

Gone, in a fleeting generation: French as the verbal currency of European diplomacy. Vanished with it, formality, courtesy, the perfumed turns of phrase, irony as weapon -- all replaced by the boorish yet unconquerable "bottom line." Yes, it was during Abu Moses' time that the English language had begun its cultural search-and-destroy mission round the planet. And should, say -- oh, the Libyans -- decide to bomb a symbol of the West, they no longer chose a crumbling, mildewed British embassy on some sedate, 19th century boulevard, but rather a neon-thrashed Berlin discothèque blaring the mercilessly cheerful ABBA or "Thriller" -- the fading gamine Michael Jackson's jaunt through noir.

In those days, Abu Moses carried on a long-running but doomed love affair with a tawny, waiflike girl with the puffy eyes and gentle stupor of a petite drug addict. The young woman's parents (mum, a blond Muslim Kosovar from the prewar elite; father, a former Egyptian engineering student returned to his Yugoslav alma mater as diplomat) resided in the upper-class Belgrade neighborhood of Dedinje, alongside the domestic Communist nomenklatura.

The couple had forbidden their daughter to marry Abu Moses (having discovered his identity via an errant love letter) and virulently disapproved of the girl's liaison, at one point threatening to disown her should it continue. Their objections to the young man, it should be noted, were not moral ones: On the contrary, a commando was simply poor marriage material, unable to earn a salary one could boast about at embassy cocktails and unfit to provide them a suitably opulent lifestyle in their golden years. The recent (and bumbling) Achille Lauro assault, during which young Palestinian commandos hijacked a Mediterranean cruiser and killed an elderly, wheelchair-bound American tourist, coupled with those ghastly shootouts at the Rome and Vienna airports, had made a mockery of the Titoist soft spot for resistance groups and rendered dinner chats with Western diplomats unbearably awkward.

Meanwhile, the girl -- sweet, dull-witted, ever teary from the imminent breakup -- was sheathed in a sort of heroin permafrost, and headed nowhere. I was fond of her because she lacked the nasty, usurious edge of many Yugoslav girls who frequented Arab circles. Also, I never saw her in any condition but slightly drunk.

Returning to the city after travel abroad, Abu Moses would hide away at the apartment of his best friend Walid, our mutual friend, and arguably the least political Palestinian in all of Belgrade. A hulking beauty of a man with a luxuriant Afro resembling Gen. Gadhafi's, Walid owned a miniature German washing machine and kept house like a woman, replete with the broom sweeps and shooing sounds of a grandmother.

"Donkeys, donkeys! I'm cleaning!" Walid would mockingly scold, whisking breakfast crumbs over the feet of Abu Moses and the girl, who both giggled, bleary-eyed and barely lucid, having just tumbled out of bed at 2 in the afternoon. Walid's father was a devoutly religious mukhtar from a village near Jenin, blinded during an accident at the Düsseldorf chemical plant, where he labored for 20 years without returning to his homeland: The Israelis are thugs, he told Walid, but I'd rather live under their boots than the godless communists any day.

And so where Abu Moses went and what he did while away from Belgrade was never mentioned aloud. In fact, so little was said about Abu Moses' life outside that it came to seem a fiction, then to fade away from our consciousness entirely. The Balkans were a universe unto themselves, and while in those years PLO operatives were heading out on raids from ports throughout the Mediterranean -- from Athens, Tripoli, Cyprus -- it seemed unfathomable that Abu Moses could be a part of it.

Abu Moses remained Walid's opposite in every way: his ebony hair lacquered flat; prancing eyes; tight, economical movements; the quick jokes that brought to mind some wisecracking Chicago gangster, a sort of Mickey Rooney in fatigues. He was also a head shorter and a good deal more street-savvy than the rest of the cohort.

Abu Moses never claimed to be anything but moderately clever -- a notion that may have been deceptive. He did, in any case, relieve me of considerable harassment, if not worse, from bored young commandos who could not imagine why I chose to live in the dead-beat morass that was the Balkans when, as an American, I could surely be living in either a Hollywood sitcom set, a mansion, or a sprawling Colorado ranch of the type featured each week in campy reruns of "Dynasty." Over time, several had become convinced that I was a spy, if for no particular reason save my paternal grandparents' religion -- Judaism -- a faith that had, over the millennia, morphed into a sort of ethnicity, and later the stated raison d'être of an entire nation, one that had -- in the young commandos' not unreasonable view -- usurped their ancestral lands.

"Who is she and what is she doing here?" a group of them had questioned Abu Moses morosely, after finally cornering him one afternoon at his desk at the Jordanian Embassy, safe harbor for the stateless Palestinians. Spy rumors were rife, a way to pass the time. They could also have serious consequences and required a fairly solid rebuttal.

Apparently (according to Walid, who later divulged the incident), Abu Moses had, in his relaxed but unequivocal way, replied that I was a friend, the best protection that one could hope for under such circumstances. I never knew why he did it. Nor did I understand at the time just why Abu Moses' word carried such weight among his peers, but as the rumors faded, I slowly came to understand that it was final.

From time to time that year, around Walid's supper table Abu Moses would toss off bits of sober advice: When Ronald Reagan decided to bomb Libya, he warned me away from the protest marches spilling out into the streets of Belgrade.

"They won't believe you're against it," he said simply. (There were few Americans in the city then; the most visible were at the embassy compound, known to be a sort of elite social club for CIA adjuncts and their families -- and a place I'd resolved never to go near. Times were tense, however, and, as Abu Moses indicated, such distinctions between oneself and one's compatriots could not be counted upon.)

And so Abu Moses patiently described how one identified the Libyans living among us (flashy billfolds, bright-hued Mercedes). They were the one group, he warned me, that enjoyed total criminal impunity -- Libya was, at the moment, Yugoslavia's key petroleum supplier -- and as such, the Libyans were the wild card in Belgrade. It would be important to stay clear of them.

And so it was that when I was followed by a tangerine-colored Mercedes one moonless midnight walking homeward past the city's rambling New Graveyard, I knew enough to reply to the two men who had cut me off on the sidewalk and then rolled down their windows to interrogate me that I did not understand them, and was Greek.

Despite these intrigues, Abu Moses and his circle remained a side story those years in Belgrade. Our daily lives consisted of far more mundane enterprises: the constant hunt to obtain food more palatable than the interminable pork and fermented cabbage ladled up at the collective dining halls (while a single gleaming orange, shipped in from Spain and then cruelly displayed in specialty-shop windows, cost a day's stipend). The capital's phantom phone directory listed only the most established residents, and in any case, none of us had access to a phone. Contacting anyone, therefore, meant half a day's journey across the city -- on foot, or via whiplashing tram car -- with better-than-average odds that the individual sought would be absent upon one's arrival. There were the daily battles with stingy landlords over the amount of coal required to keep the frigid winter at bay and our mind on studies. At school, a corrupt professor or two might make clear that a stereo, hard cash or something rather more personal would guarantee high marks. And finally, there were the near-peasants given State desk jobs, who so relished making the city-bred beg that securing official stamps for the right to study, or rent, or work might take months of groveling.

Life went on and, as anywhere, word circulated in student circles about our classmates, including the young Palestinian operatives. They ranged from spoiled rich boys who had grown up in luxurious Libyan exile (and whose parents sent a son to join the PLO as a matter of prestige, as families elsewhere do to the monastery or priesthood) to gaunt refugees from wretched Syrian camps, dressed always in threadbare suit coats, full of the quiet rage of the disinherited, with nowhere to go but up.

Abu Moses, I now realize, spoke little about his own origins. And though he was with us for two winters and the spring and summer in between, my knowledge of his past remained as skeletal as of others with whom I'd scarcely spoken: a few late-night references to the Expulsion, a casual mention of his ancestral village, a moist-eyed, soft-cheeked yearning for the Land -- as one longs for a grandparent left behind, whom one has grown up adoring but has never met.

Piecing these fragments together, it can be said that Abu Moses' story was not an uncommon one among the ranks. In or around 1948 (the year marked by the Israelis as Independence, and by Palestinians as al Naqba, the Catastrophe) his family fled their village in Palestine, somewhere near ancient hilltop city of Safad. The occupying British, through a system of unequal reward, had managed to divide -- but not conquer -- Palestine's local Arab majority and Jewish minority, then washed their hands of the region, leaving the two groups to peck each other to pieces, like some vicious Levantine cockfight. When combat subsided, Abu Moses' ancestral village lay within the borders of the nascent Israeli state.

There was the family's life in exile, as refugees in Lebanon. Abu Moses (baby Ibrahim), born a dozen years later, dragged from camp to city slum. Recruitment as a teen into the PLO, driven by the vision of one day retaking the family home from the Israelis. Training camp somewhere along the coast, a show of promise, some distinction. The Israeli invasion and war of '82, the evacuation of Palestinian fighters from Beirut; news of the massacres. Later, a PLO scholarship to Yugoslavia, where he would ostensibly study tourism (the least-pressured course of studies and one that could provide a young commando a visa, minimal cover, and a home base for European operations).

Even now, it is with effort that I assemble the outlines of Abu Moses' tale. In Belgrade, he was simply the affable friend-of-a-friend who dropped in unexpectedly every few months, a sometimes tiresome cutup with a penchant for practical jokes, uninterested in academics, an acquaintance who had once gone out of his way to do me a good turn.

Winters were a deadly bore in Belgrade, a capital city that supported little nightlife of any kind. An exciting Saturday evening might consist of, say, selling a used sheepskin coat for a pile of wilted deutsche marks or procuring black-market airplane tickets from some Polish shark.

Days were pure drudgery. One gray January afternoon I found myself beating back the snow flurries, running through the sooty, cobbled streets of Abu Moses' Dickensian neighborhood. To escape the weather, I decided to drop in on him at home. Though our conversations had never been particularly fluid or engrossing, I was certain that we could find something about which to complain (the acknowledged national pastime). Probably it would be Walid, at whom we were both miffed since New Year's Eve, after he hopped a night train to party in Sarajevo, leaving us to drink brandy at the Hotel Slavija with some boring mafia hack.

In any case, when Abu Moses opened his apartment door that afternoon and bade me enter, he was distracted, barely registering surprise at my appearance. Normally an unfailingly polite and attentive host, now he was unsettled, jumpy, on edge -- nearly rude -- mulling around the dim, red-and-black-carpeted flat. Perched everywhere, gift flasks of men's cologne and Scotch whisky, bought in airport duty-free stores, gold-foil seals yet unbroken.

"I'm going on vacation," Abu Moses piped up, as tight-lipped and agitated as a methamphetamine freak, searching my eyes intently for a moment, then lost again in his demons. "To Cyprus," he added then, as speaking to someone who wasn't there.

I'd passed through Limassol a year before. Mention of it brought to mind dried-plum sweets from the mountainous interior. A certain grandmother that reminded me of my own. Roman mosaics of gods and centaurs paving the very shore of the Mediterranean, their edges crumbling into its ancient, lapping waves.

"Pa, odlično.That's fantastic," I said, attempting good cheer. We were all envious of anyone who could escape the blizzard-choked city, and I felt the pinch of it -- but had hopes that Abu Moses' humor would improve if we shifted to a more pleasing subject.

Instead of mellowing, however, Abu Moses only grew more restless, like someone scurrying from end to end of a steel cage. I figured that I'd come at a bad time -- problems with the girl again, or money perhaps; something that blunted his characteristic verve. Seeing that our visit was unlikely to improve, I slipped my purse across my shoulder and began moving toward the door, when I felt Abu Moses grasp my arm.

"I've got to show you something," he anxiously insisted, and then, as soon as he was sure I would remain, he cut across the living room and begin fitfully rummaging through stacks of paper propped behind a dresser. Tension-filled minutes dripped by, a half-hour nearly, until I began to find Abu Moses' angst unbearable.

"It's here, he muttered, "I know it" -- flinging more pages off the book piles lining the sides of the room. In the midst of mentally charting my departure once again, I heard a huff of recognition: The document had been found. Still, from the tension in Abu Moses' shoulders and his wet brow, it was clear its discovery had brought little relief.

"Read this!" he said urgently, sitting me down beside him on the tweed couch and pressing a set of photocopied broadsheets into my hands. I sighed, having little interest in sifting through some propagandistic tome, and no intention of staying long.

Abu Moses, however, sat erect as a grade-school pupil, flicking through pages, and underlining whole phrases with his blunt finger. I calculated how long I would need to feign interest and remain polite. Then something bizarre caught my eye: On the front page of a news sheet, clearly embossed along the top, was the masthead of the Israeli Communist Party, the text below proclaiming the rights of Palestinians to their civil liberties.

The sight of that document there in that blizzard-bound Balkan den struck me as so incongruous that I could barely assimilate it. Lost in a sort of mental blur, I sat trying to make order of the elements, when all of a sudden I felt Abu Moses catch my shoulder, spearing the headline with his finger as he cried out half-madly:

"You see? You see? They are human beings too! The Israelis. They are human beings too!" -- as if I, with cousins and friends in Haifa, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, had somehow to be convinced.

And yet this he continued to do, feverishly reading aloud each paragraph, beads of sweat flying from his face, stopping every so often to declare, "We're all the same!" like some sort of anguished challenge to an invisible adversary.

Between one jolt and another, my thinking was not particularly clear that afternoon, and I cannot recall all that happened. I do remember, just then, a sense of unwanted burden, the notion that I didn't know the man well enough to sit through his personal manias and obsessions. That I simply wanted to be somewhere else.

And so I began again to stake out a route to the front door, about to rise, and mentally preparing for the inclement weather when -- without warning -- I was pinned down by something large and round and leaden that had fallen into my lap.

For a split second, my eyesight went blank from fear, or astonishment; when I finally looked down, I saw that it was Abu Moses' head, face buried in my stomach, his torso thrown across my lap like a casualty.

The intimacy of it bewildered me: Neither lovers nor close friends, we had never so much as embraced in greeting. For a second, the notion flitted through my mind that the man was simply suffering from nervous exhaustion. A moment later, I felt the white heat of his tears seep through my woolen trousers, still cold and damp from melted snow. Under the weight of his skull the coarse weave scraped my thighs, but I remained unmoving, under the spell of some vague but pressing sense of being there for some purpose other than my own. A moment later, Abu Moses' shoulders rose and jerked in silent spasms, then gulping sobs.

What are we responsible for remembering? What is the duty of the confessor, of the witness?

Looking back now on that snowy afternoon at Abu Moses' place, the last time I would see him, it took longer than one might expect for me to comprehend what the trip to Cyprus meant. Indeed, months of denial and doubt. What I do know is that in that slim, suspended moment, time and space contracted, everything real had vanished, all that remained was a weeping man, and the act of witness.

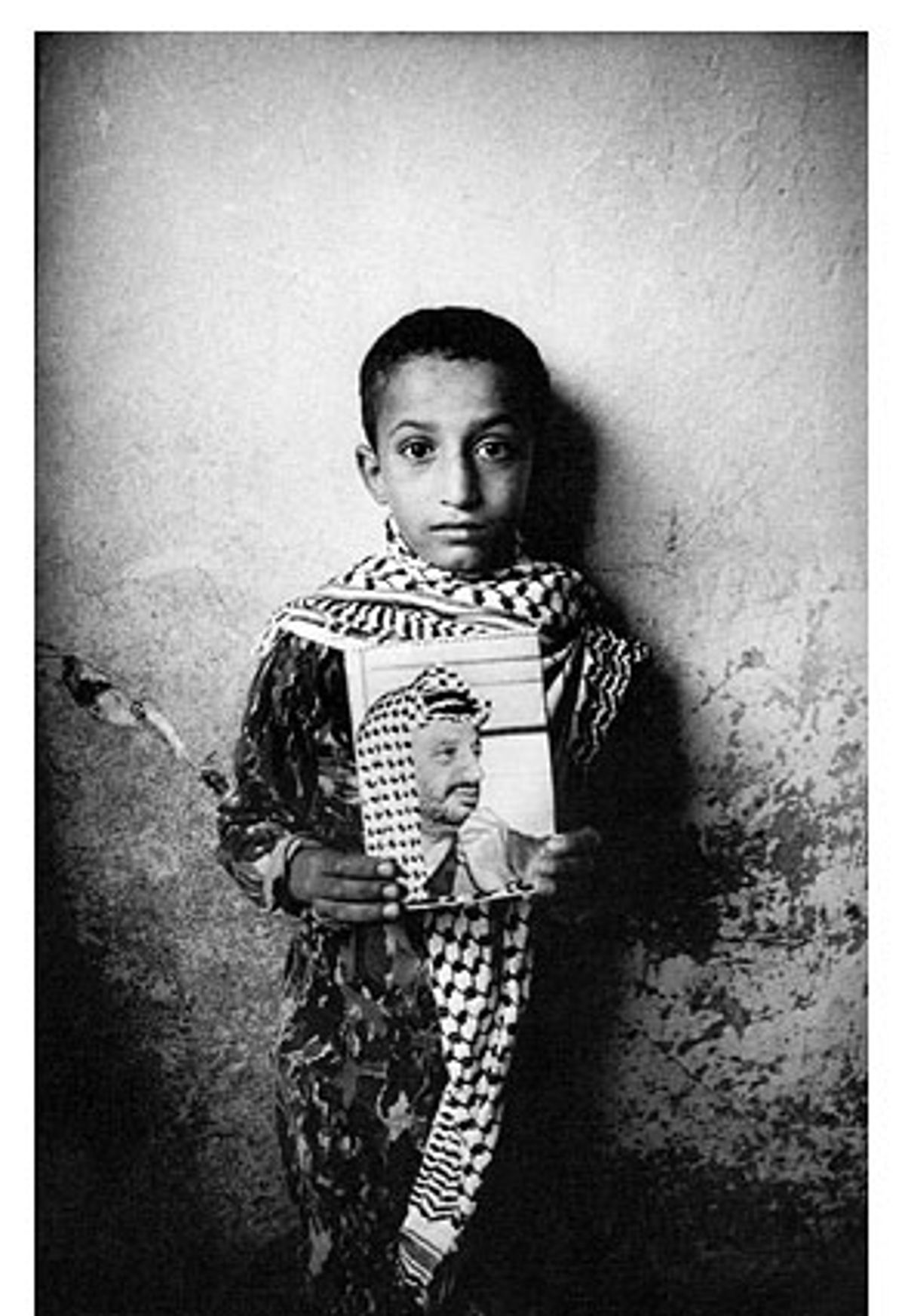

In this light, that afternoon, I recall glancing down for a split second -- from what seemed like years away -- at the bare nape of Abu Moses' neck. The brilliantined hair, the squarish skull. How closely his small, compact body resembled that of a young boy.

And how, at that very same moment, he turned a furious, tear-stained face toward me and rasped for a final time: "My God, they are also human beings!" -- glaring up at me with the wounded eyes of a betrayed child accusing his mother of the crime of having no answers. And of colluding in a world that is brutal, and senseless.

Shares