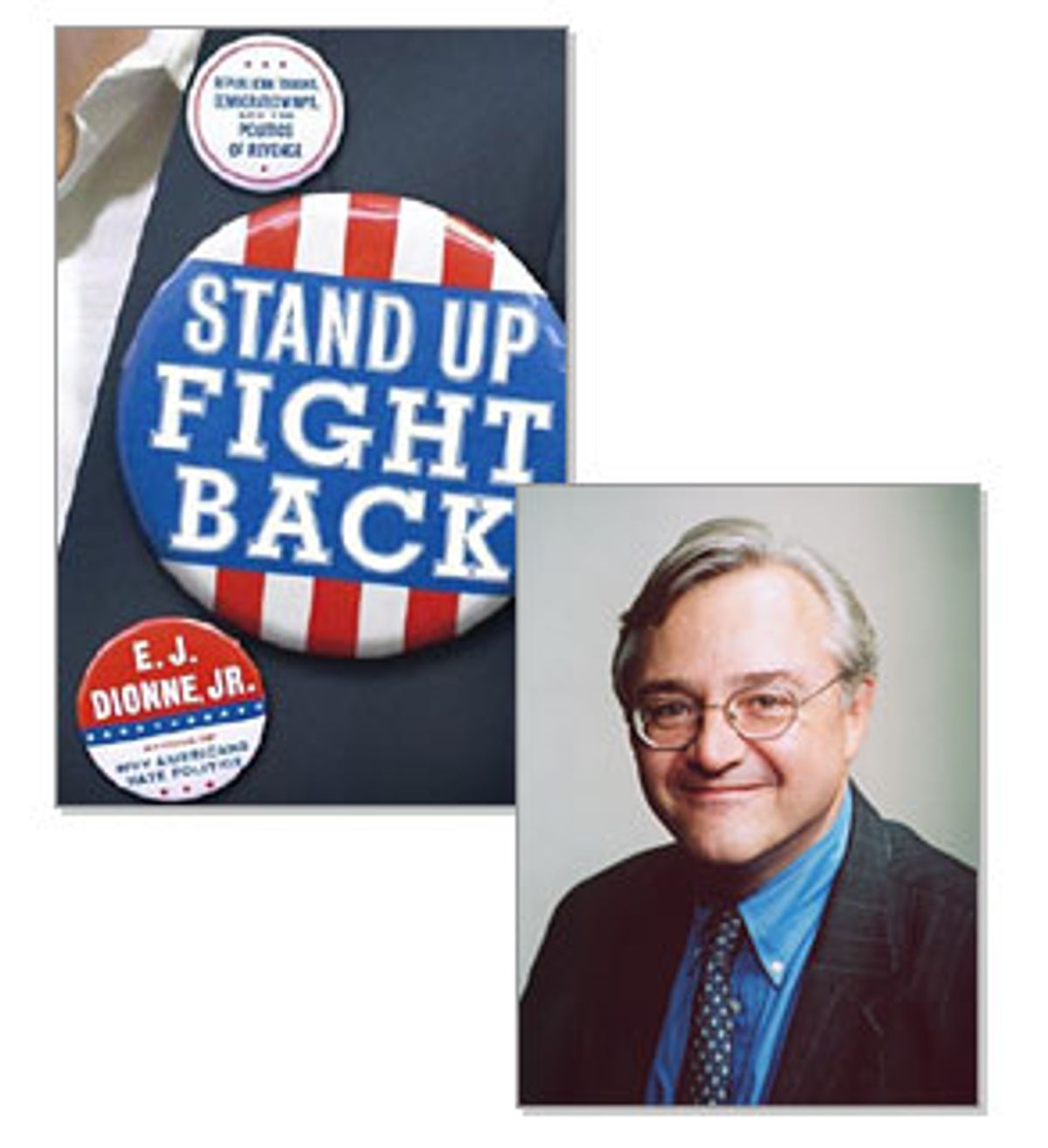

Sure, liberal Democrats are enraged by President Bush. But when independents and moderate Republicans find themselves shaking with the same sense of outrage, that's when you've got a potential political realignment on your hands, says Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne Jr. in his new book, "Stand Up, Fight Back: Republican Toughs, Democratic Wimps and the Politics of Revenge."

Dionne, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of the 1991 bestseller "Why Americans Hate Politics," contends that Bush squandered a historic opportunity to unite the country after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Americans who put aside differences to rally behind Bush after 9/11 -- and in return got an invasion of Iraq and two-fisted partisanship in the 2002 midterm elections -- now feel like suckers, Dionne says. "How," he laments in the book, "has a fundamentally middle-of-the-road country gotten a politics characterized by so much meanness and division?"

In Dionne's view, most Americans are neither far left nor far right; they are moderates who have been left bound and tied on the train tracks by an increasingly radical and all-powerful GOP. Dionne desperately wants Democrats to come to the rescue, but he fears his heroes' knees will knock: "The party that once galvanized a nation by declaring that there is nothing to fear but fear itself had become afraid," he writes. To repair the party, Democrats should "stop talking about what they are not" and instead announce what they are for: economic justice, fair play, strong communities, tolerance and public service, he writes. They must take back the language of morals and religion from Republicans. And they must fight not only harder but smarter than Republicans. Otherwise, this historic opportunity to return America to equilibrium will be lost, he argues.

Dionne, who is also a professor at Georgetown University and a regular commentator on National Public Radio, chatted with Salon recently about his thoughts on the political scene.

The title of your book is "Stand Up, Fight Back." Whom are you urging to action -- the Democratic Party, or the moderate center of the American public? Because independents and moderate Republicans are a vital part of that center.

When you ask the question that way, that is indeed the way I think of it. In the first instance, I had in mind the Democrats. But then there are also moderates and, to a large extent, that section of the Republican Party that's been frozen out of authority. I think the American people should be fighting back against a kind of divisive politics that is not serving anybody.

One of the core themes of this book is that after 9/11, President Bush was given an enormous opportunity to reunite the country and create a new kind of politics. And we were very united for a while. But I think when historians look back on this period, one of the strongest criticisms they'll make of Bush is that rather than using this moment to put aside the worst kinds of divisive politics -- he divided the country on a homeland security bill, for goodness sake -- he has pushed through more tax cuts and he pushed through the Iraq war. So I have the sense there is a reaction in the country not only to the failures [of the administration] but also to a divisive tone [that] people are subscribing more and more to the folks who currently dominate the Republican Party.

So is it useful then for Al Gore to call on Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, CIA director George Tenet and other administration officials to resign? Or is that what you mean by "standing up"?

I was trying to figure that out myself. Another important theme of the book is a frustration with Democrats, with liberals and progressives, because they seem to have lost their nerve. And to a considerable degree, I think that having other Democrats and liberals out there taking strong positions is probably more helpful [to John Kerry] than harmful. The Republicans have been very good at this division of labor. President Bush has not said the harshest things but left that to other people. I think Gore is playing the role of a kind of outrider. He'll ignite the conservative talk circuit, but I'm not sure that's very relevant, because those people won't vote against Bush anyway. A bunch of people might say [of Gore], 'Isn't that a little extreme?' But people move the debate by saying things outside the mainstream. Conservatives have been much more skillful about that over the last 30 years.

Your analysis has always been pretty measured. But this new book seems much punchier than is typical for you, more angry about the state of political discourse and frustrated with where attack-style politics has taken the country. For example, you quote Rich Lowry writing in the National Review that Clinton "forged a kind of amoral majority, consisting of Hollywood and ... pro-abortion feminists, urban secularists and a swath of straying husband and wives," and then you observe: "Now there's an astonishing take on a country that elected Clinton twice." So, how angry are you?

I am basically a liberal in my politics but a moderate by disposition. I have a lot of conservative friends I like and learn from. I don't think conservatives are evil people. So for me to feel this level of anger and alienation is surprising. I found that's true for an awful lot of people -- for people who didn't feel this when, say, the first President Bush was in power. So even though, yes, I'm a liberal, I don't think I'm that unusual in the country. Some of the things that have disturbed me have disturbed people who are not ideological liberals. I talk in the book about how after 9/11 my son and I stopped at a filling station owned by immigrants from India and they gave my son an American flag that he put on our car. That was the mood we were in in that period. I sort of ceased and desisted in my own criticisms of President Bush, and I think there are a lot of people like me now who feel burned. The thing that really bothers me is how Bush used 9/11 as a battering ram against a segment of the population that has really proved itself to be as patriotic as Republicans.

You write that by virtue of the GOP's sharp veer to the right, the Democratic Party now "carries the banner not only of the left but also of the center." Yet you also express doubt about Democrats' ability to speak to the center, to find its voice. And if the Democrats don't figure it out, you say they'll miss their "rendezvous with destiny." So how well do you think John Kerry is meeting this challenge?

Can I divide it into two parts? Into what Kerry has done right and what he has done wrong? The book argues for a patriotic progressivism. The way Kerry invoked his Vietnam service in the primaries spoke to a lot of people who are not part of the liberal base. And if you think, as I do, that there is a need to marry patriotism with progressive values, that's a good start. I also think his repeated references to John McCain are a good idea, because they appeal to those Republicans who are very uneasy with what's going on right now. What he's done wrong is perhaps looking too mechanical in moving left in the primaries to get the Dean vote and then obviously moving to the center in the general, when I think his main task is to get the election to be a referendum on Bush. The Republicans are really smart to use the flip-flop thing because it's a way of saying Kerry doesn't know who he is. They're trying to make him an unacceptable alternative to a not-very-popular president. But the flip-flop thing has its limits. People are cynical enough about politicians not to be surprised if they change positions.

At the same time, what's happening in Iraq has increased people's sense that nuance may not be such a terrible thing. But I think the attack is more about character. Kerry has got to be someone people are comfortable enough with that they'll use him to throw out President Bush. That's why I think the flip-flop attack should not be underrated.

You recap some of the harsh criticism from Republicans of Bill Clinton, including Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who once called the president a "jerk." You write: "It is astonishing that Republicans should now be shocked that Democrats might finally decide to use comparably tough words to criticize a Republican president." So what do you make of Democratic Sen. Tim Johnson of South Dakota retracting his comparison of far-right Republicans to the Taliban? He ended up abjectly apologizing.

Oh, I don't know. Probably comparing anybody to the Taliban is not a good idea. There is a sense of frustration with conservatives who ally their cause with the cause of God, and there are plenty of non-Republicans out there who are believers, and they are frustrated. But I don't like accusing anyone of being like the Taliban. Personally I think Tim Johnson is a good person and not an over-the-top guy.

You also argue there's a double standard among conservatives, who consider that "any attack on Bill Clinton was morally justified [but] any attack on George W. Bush was a sign of lunacy."

One of the problems with the public debate is that serious conservatism has been replaced by attack conservatism. But there is another style of conservatism that is not really conservative. It is -- what's the word I'm looking for? I don't want to use the word "radical" because it's a word I actually respect. It's more about public relations, making the convenient argument at the right time, and it's also about celebrity.

Far from being conservative, the right has been quite radical in manipulating American institutions in novel ways to achieve political goals, you argue. As examples you cite the impeachment of President Clinton, the Supreme Court's partisan 5-4 decision to stop the 2000 Florida recount, the recall of California Gov. Gray Davis and House Majority Leader Tom DeLay's breaking tradition to push through a mid-decade redrawing of congressional districts in Texas. Do you see a line from such "radicalism" to the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal? The Bush administration has, after all, made clear its disdain for the Geneva Conventions and international law.

The founding document of our country refers to a decent respect for mankind. That's what we were founded on, and most of these international documents were written with enormous American input and stamped with our values. So to turn your back on them because it's convenient is not only a mistake, it's simply not in the country's interest. It's decidedly un-conservative to use institutions this way. The five judges who ruled in favor of Bush had to really, really stretch their principles to get to that result. It's not good for a conservative justice to do that. Reapportioning districts in the middle of a 10-year period is very un-conservative, because tradition says you do it once a decade and you live with it until the next time. There are a lot of traditional conservatives who understand that human nature is flawed and needs to be hemmed in by rules, and they have doubts about the direction we're going. I think conservatives have been pretty good at taking on liberal inconsistencies, and sometimes the conservatives have been right. But it's now a good time to take on conservative inconsistencies as well. One of the things I find fascinating is there are a number of people in the military who are not happy about how things are going. These are people who at heart are Republicans and conservative.

Speaking of conservative inconsistencies, what about House Speaker Dennis Hastert lecturing Sen. John McCain on the meaning of sacrifice for your country? I mean, come on. McCain spent five years as a North Vietnamese POW, with two years in solitary confinement.

The question which I've been asking myself [about Republican rhetoric] is, Has the bottom completely fallen out? I don't think the bottom has completely fallen out, but there is a danger for the Republicans that it is on the verge of falling out. When Hastert says something like that, it is the kind of over-the-topness that is now getting criticized and noticed. What has happened in the last six months is that things the media and the Democrats used to let slip by aren't slipping by anymore. There's not an automatic, "He's the president. It's unpatriotic to criticize him." That view is no longer there.

Shares