I'm driving with my 14-year-old daughter and scanning radio stations when I hear a mellow love song. "That sounds like what we used to listen to in the '80s," I say. It's the muffled electronic drums and smooth, soft R&B rhythm of the '80s, the light floaty voice like DeBarge or Switch, but an echo of someone else.

"It's a Michael Jackson song," my daughter says, rolling her eyes. "He sounds like he's choking on a peanut or something."

She leans forward to poke the button. "Don't change it," I say, listening more closely. I have never heard this particular song, but the shadow of the beat takes me back -- back to when Michael Jackson was the sexy yet innocent soul singer with Milky-Way skin and huge Afro who ruled the girls in my neighborhood.

This week, Jackson was cleared of allegations that he molested a boy in Los Angeles in the late 1980s -- but still awaits trial in Santa Barbara on charges of molestation of a child at his Neverland ranch. But we're listening to the Michael Jackson of my own youth, his voice spiraling into the car windows.

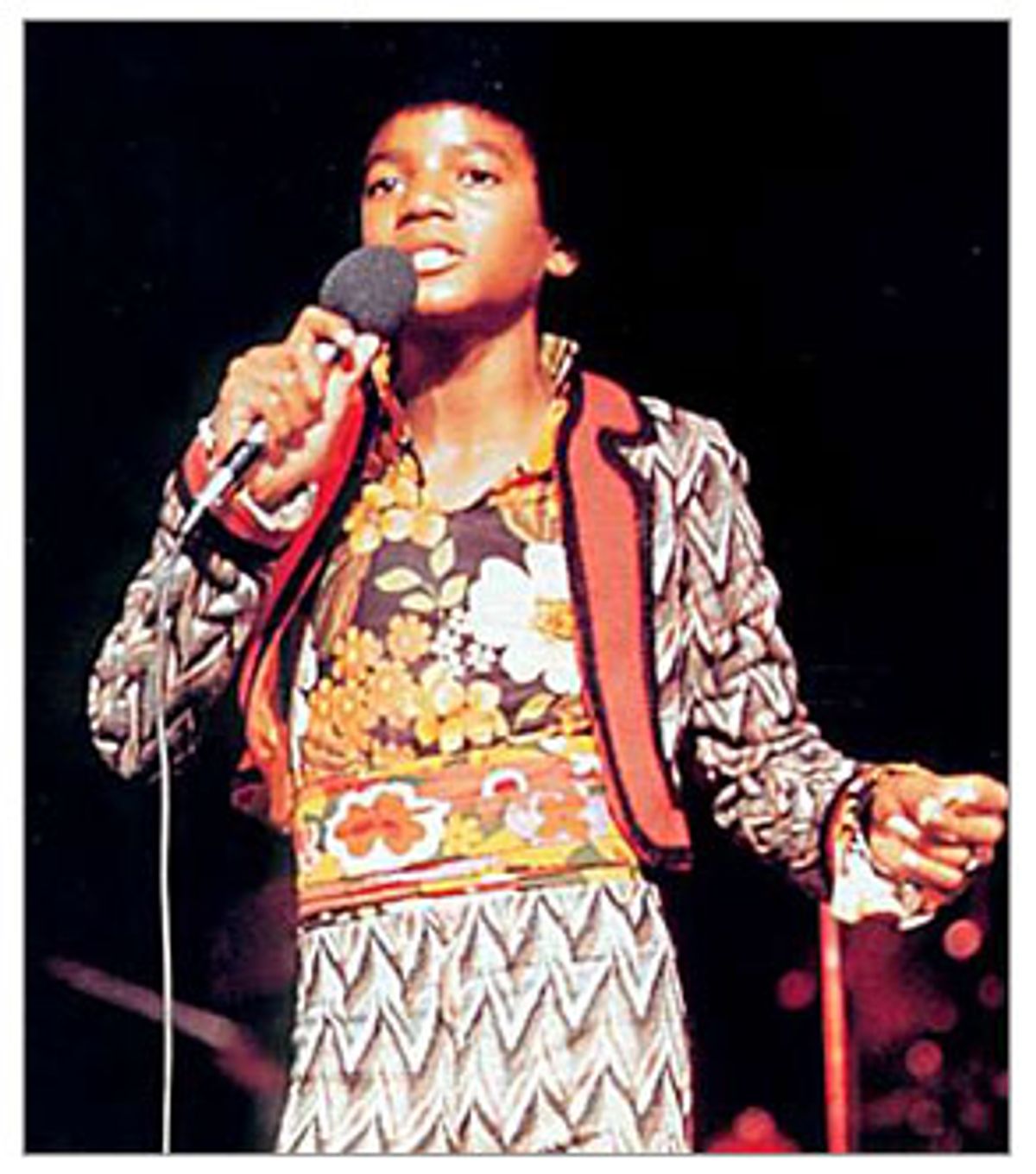

In my Southern California city, and all over America back then, in racially mixed working-class neighborhoods like mine, millions of young girls watched him on television as he clutched the microphone to his chest and bent over with the weight of his love for us, throwing out his brown fingers, pulling the air toward him and moaning, "I want you back!" Thousands of girls screamed and swooned the way others -- white girls -- did for the Beatles or the Monkees. But Michael Jackson and his brothers, as the Jackson Five, were the dreamboats of black America.

Now I look over at my daughter, my oldest, and can't figure out how to tell her that in 1978, in these orange groves we're passing just a few blocks outside my old neighborhood, her father and I used to park his sister's beat-up Pinto and kiss for hours while Michael crooned from the cheap speakers in the door. "Let me show you the way to go," Michael sang, his voice growling deep, catching with emotion. "I'll never let you down, put your hand in mine ..."

"Mom, can I change it now? I don't want to hear this." I glance over at my daughter's lovely caramel face, her long black hair resting in curls on her shoulders. Her mouth has curled in more than disgust at the whispery voice.

"This song is crap," my daughter says impatiently, "Nobody listens to anything by him." She looks out the window. "Everybody hates him."

For my younger daughters, 12 and 8, who never knew him as brown like them, as a singer and dancer who could captivate an audience of adults and children alike, he has always been a figure of shivery fear. Whenever we see the first ghostly shadows of his face on television news shows, someone turns the channel very quickly, sometimes even looking away until Michael Jackson is gone.

But my oldest daughter feels a more intense dislike, because she remembers when Michael Jackson looked something like her. Not his childhood or teen self; he resembled her in his early adult years, circa-"Off The Wall," as he started to become lighter, with long wavy hair and toast-colored skin and that sparkly jacket. My daughter liked sparkly clothes then, too; she was in preschool.

We're only a few blocks from my childhood home now, and I think about being in sixth grade, the only white girl in my dance group, as we performed on our elementary school stage to "ABC," dancing a twirling, hip-rolling routine to imitate Michael and his brothers Tito, Jermaine, Marlon and Randy.

With his wide nose, maple-syrup skin and that huge natural, he looked like a thinner version of my boyfriend, whom I met in eighth grade and went on to marry. At school dances, all our hella-tough friends did the robot and the Moonwalk; they pop-locked to "Dancin' Machine," and nobody made fun of Michael Jackson. Jermaine was the cool handsome older brother, Tito the quiet one -- but Michael was the one who sang to us. When Michael went solo -- I was a high school senior -- we listened to all his hits. He was the suave, sure voice we danced to at house parties, or while cruising. He was safe but sexy, the favorite among every black woman friend I had, the alternative to James Brown, who the guys liked better because he was rougher and more political. The guy groups like the Spinners and the O'Jays and the Stylistics were big, but if you asked my girlfriends who they wanted, it was Michael, even as he was reinventing himself with hair products and what we suspected was eyeliner. He was misunderstood, he was soft enough to understand us, he wasn't dangerous (not yet), and he was so pretty, with those huge eyes and delicate brows and sad mouth.

If someone had told us that in 20 years he would be white as a powdered ghost, that he would be repeatedly suspected of sexual behavior with children, we would not have laughed. We would have rolled our eyes and said, "Michael? The one who begs us to come back, to give him one more chance?"

But my daughter is rolling her eyes now, with real anger over my sentimental hesitancy to change the station. Michael Jackson is still singing, his voice wavering and floating thinly from the dashboard. His nose is like a sharp weapon, I was thinking, his skin pale as bleached muslin, his hair hanging in quills about his etched cheeks. She says, "Mom! Turn it off! No one wants to hear him. He's so desperate."

All these years of seeing his face stare out from newspaper photos, from magazine covers, from the television screen -- she, along with so many other African-American teens, considers this man not just someone who behaves inappropriately with children, but a scary presence.

But I remember when this same teenage daughter, at 2, begged to stay up late and watch the Michael Jackson special on TV. She was entranced by the precise dance moves and silver glove. That's what he was by then, the silver glove, the pulled-up heels and spins, but he was so cool that she drew a her-sized picture of him, glove and hat and milky-tea colored cheeks and wacky joints, and taped it to our back porch door.

Whenever I try to tell that story, she says, "Don't you ever tell anyone that I liked him or even that I listened to him sing!"

Hey, I want to tell her -- he was the scarecrow in "The Wiz," the black musical movie version of "The Wizard of Oz," and our Dorothy, played by Diana Ross, trusted Michael Jackson's shambling, cool-dancing character to lead her down the yellow brick road. He wore a Reese's candy wrapper on his nose back then, as part of his costume. A brown, crinkled cup for a nose, for the scarecrow we all loved. What could he possibly fasten onto that damaged, sharpened nose now? What costume is he wearing, as himself, a man who lives a fantasy none of us understand?

He hung there on our back door for five years, dancing on the wood, until the marker-colors of his skin and clothes faded from the sun, and the true colors of his face faded from surgery and vanity and what we can only diagnose as self-hatred. That's the unspoken reason my daughter hates him now. She says, "He hated himself so much he made himself into a white guy." And in doing so, he erased someone who bore a resemblance to her. She says, "How sick is it to not want to look like anyone else in your family? You're saying your parents really messed up."

According to teens, listeners like her, his current music represents a pathetic attempt to win over people who won't give him even two minutes; he'd be better off sticking to fans in other countries, not her and her friends, who listen to Norah Jones, Audioslave, Black-Eyed Peas, Outkast and System of a Down. My daughter and I have spent hours discussing current music, and she finds it hilarious that Justin Timberlake, as white as can be, has recreated himself as M.J., replete with glove and spins and hat. A white guy reinventing himself as a black guy who's transformed himself into a whiter guy. And my daughter, who can check seven boxes on a racial category list due to her mixed heritage, laughs when white guys try to impress her by declaring, "I listen to Eminem."

"Really?" she replies, coolly. "Why?"

Her current favorites: the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Clash.

I tell her I don't think Michael Jackson ever got to be a child himself. He was performing constantly, like many child stars who grow up to have mercilessly unhappy adult lives. I was 11 when I danced to his songs, and he was 12, already enduring long hours and road trips and endless work. Maybe that's why he made Neverland, his ranch in Santa Barbara, into a child's paradise. For the childhood he never had.

"But why would any kid want to go there?" she says. "Who would want to hang around with him?" If the charges are true, Neverland is a child's nightmare. And forever, while I remember Michael Jackson's sweet soulful voice and perfect Afro, my children will remember his face as the representation of a fearful spectre, a haunting danger clothed in sparkling military garb. We are leaving my old neighborhood now, and the song is almost over. We are cruising over an old railroad bridge and I glance at her, gold-brown arm propped on the open window, her black curls moving in the breeze, her full lips. "You used to love him, when he looked like you," I say. "Remember that picture you drew?"

"Yeah," she says, looking out the window, away from the fading voice on the radio.

Shares