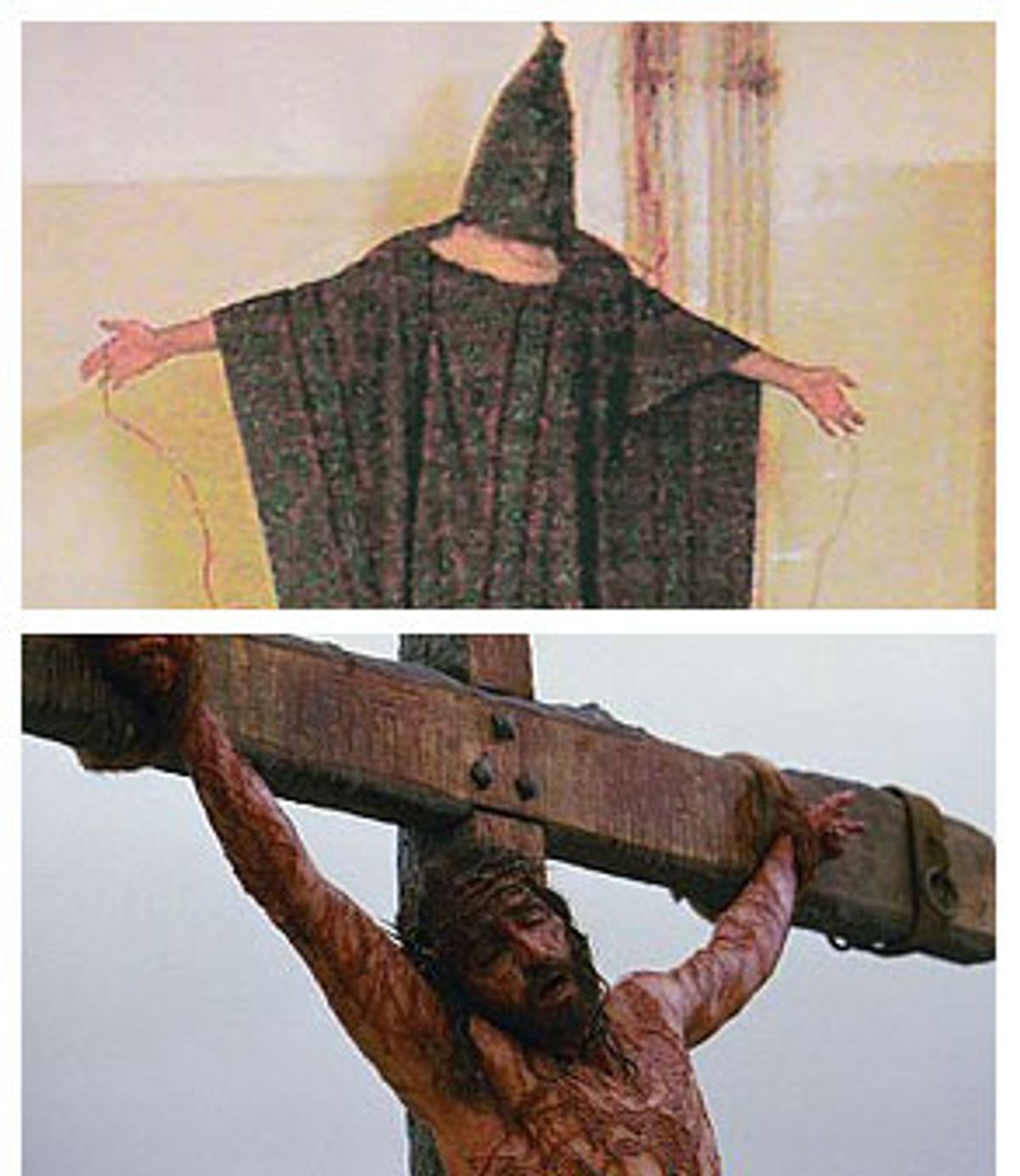

Twice in the last few months torture and its graphic representation has been at the center of public discourse. The first time had to do with "The Passion of the Christ," a film that features more violence than any big Hollywood movie before it. The second time -- now -- has to do with the events at Abu Ghraib prison. The two spectacles reveal disturbing truths about American politics, sexuality and spirituality.

It's easily observed that torture has a highly developed aesthetic dimension. Medieval instruments of torture are gathered in dedicated museums and traveling exhibits all over the world. Those very instruments, of course, were often used in public. Torture, despite its need for secrecy, also needs its own representation. It's usually meant not only to inflict pain but to instill terror. It's sometimes meant to please the torturer. Therefore, the ritualistic, fetishistic, "spectacular" aspects of torture are an integral part of the practice. As a spectacle, torture is akin to porn -- S/M being the obvious shared territory. It elicits voyeurism and a morbid fascination.

"The Passion of the Christ" was accused by many detractors of being "pornographic." The torture of Iraqi prisoners is pornography in a very direct and complete sense. It's not just violence but sexual violation -- what is more, it's sexual violation staged and captured on camera, made into a spectacle readily available for future and expanded viewing. It's sexual violation fixed into an essential symbolic image to be preserved like a trophy. Just like conventional porn, it's completely self-conscious and deliberate yet morally unimpeded.

In a recent cover story in the New York Times Magazine, Susan Sontag criticizes Bush and his administration for their initial profession of shock and disgust at the Abu Ghraib pictures, "as if the fault or horror lay in the images, not in what they depict." This is of course richly deserved criticism, yet there's another point to be made: The horror that was depicted was largely designed for the depiction itself. It was conceived and executed as pornography.

Several of the pictures we have seen show both victims and torturers posing for the camera. There's a naked man kneeling in front of another man as if performing oral sex. A naked man on a leash held by a female American soldier. Naked men in chains. Naked men stacked up in a grotesque pile, half gangbang and half mass grave. Other alleged tortures, which may be documented by the hundreds of pictures we haven't yet seen, included forced masturbation. Whether the sexual acts were performed or simulated, the prisoners were forced into the position of pornographic "actors." Significantly, the hundreds of pictures seen by Congress after the scandal erupted included not only acts of torture upon prisoners, but acts of sexual intercourse amongst the guards themselves. The soldiers who took the pictures knew that, in both instances, they were making porn (albeit in different sub-genres.) There was no other reason to record the tortures; it was, in fact, self-incriminating and stupid by all practical standards. Except that the idea of recording the acts of torture was, to a significant extent, the inspiration to commit them.

You can sense the sexual disturbance in the minds of the soldiers responsible for this. It's a disturbance exacerbated by the months away from home, but created by a lifelong familiarity with porn -- its cynical humor, cheap patriotism, crude vocabulary of submission and prevarication. The president and his inner circle said, "This is not the America that we know." But it is. The pictures from Abu Ghraib are American "gonzo porn." They reek of frat-house hazing and gang initiation rituals, of "Jackass" and "Bumfights." They encode racial hatred and fetishistic allusions to slavery.

New York Times columnist Frank Rich points out that the right is using the "pornography made them do it" excuse to scapegoat liberal attitudes, invoke censorship and exonerate the Bush administration. This may be true, but it's no reason to gloss over the sexual nature of the torture. The torturers were enabled by specific political decisions. They were also inspired by broad cultural influences.

The torture/pornography connection is deep and inescapable. Mark Bowden, of "Black Hawk Down" fame, wrote a well-informed, compellingly readable article in October's Atlantic Monthly about "the dark art of interrogation" (which was promptly optioned for movie development.) He makes a strong case for the effectiveness of torture as a means for acquiring intelligence -- which of course is not an unchallenged notion, and not necessarily a justification. But torture is not the mere application of pain to the task of extracting information. Much of what we identify as torture is actually gratuitous, like the ear-severing in the film "Reservoir Dogs." "I believe you," says Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen), "but I'm gonna torture you anyway." This is, arguably, the real "point" of torture -- the assertion of power over the law, over pity, over logic. I'll torture because I can. I don't need a reason, I don't need a goal -- the arbitrary nature of the act is in fact its very essence. You cannot understand it except by internalizing the absolute fact that I have all the power and you have none, and our very identity as human beings is defined by this fact. You can conclude that I am not human because I lack pity. But that's an abstraction. The concrete reality of the situation is that you are not human because you lack all freedom and all dignity.

The torturers of Abu Ghraib had both a reason and a political sanction to do what they did. Yet the nature of the tortures and their recording suggests a casual licentiousness, the arbitrary indulgence of mean appetites. The two aspects -- rational justification and gratuitous sadism -- are superficially at odds but deeply inextricable from one another. I must inflict pain on you because you and your associates are terrorists, evildoers to be stopped for the greater good of mankind. But because you are an evildoer, enemy of mankind, I can also abandon myself to the pornographic voluptuousness of total control. In fact, not only can I, I must. In order to torture you, it is important that I see you as less than human, and so I will use torture to reinforce that image.

When power is exercised in such an extreme, absolute form as torture, it literally dehumanizes those it's exercised upon. And they know it. Stripped of rights, of the ability to trust a fellow human being, and most importantly, of self-respect, they lose the very sense of who they are. The identity of the torture victim can never be the same again. That's why sexual torture is central to the experience. The emasculation of men, the degradation of women, turns them into something they no longer recognize as themselves. Torture is largely the business of creating shame, indelible memories of one's own impotence which serve as warnings to a whole society. An instinctive understanding of this task can be evinced by the acts of the American torturers. They were aiming to hurt the Arab man where it counts the most -- in his masculine pride. There was hardly a more explicit way to do it than to strip him naked and capture him in effigy as the perverse negation of his own self -- as a pathetic loser, writhing on the floor or engaging in simulated sexual acts on command, while American men and women pose next to him with a grin and a thumbs-up. This instinctive understanding was further refined by the superior education in pornography that is typical of the contemporary American man (and to some lesser extent, woman.)

Pornography shares with torture an inherent ability to dehumanize. It reduces the individual to a sexual function, flattens identity to a physical act performed for somebody else's ultimate pleasure. As a performer of pornography, you relinquish your dignity going in. You adopt a vulgar, ludicrous stage name and sell yourself by the pound -- or more to the point, by the orifice. Pornography records acts of degradation to be perused, collected, lusted over by anonymous customers. A pornographic image is a trophy: the record of somebody's submission to the base needs of a customer, exercised as "power" through the laws of the market.

It is noteworthy, of course, that at least three of the alleged torturers are women. This inspires two opposite conclusions: One, that extreme situations such as war produce aberrant behavior, and a woman may occasionally go against her feminine nature and behave like the worst of men (still, that being the exception that proves the rule). Two, the participation of several women in the tortures is consistent with larger social trends, and therefore it belies the idea that pornography, rape and sexually predatory behavior are the exclusive domain of men. If we follow this hypothesis, we may conclude that porn has so deeply corrupted the female psyche that women have become willing to endorse an enterprise that is largely directed at their own degradation.

There is ample evidence in our culture to corroborate this second scenario. Women have been co-opted into watching porn, shopping at the Hustler store, patronizing strip bars. "Porn star" is a label of cool. It's routine to see actresses and singers showing every allowed inch of skin (and "suggesting" the rest) on the cover of mainstream magazines. Fashion dictates that thongs must peek out of low-rider jeans. Pamela Anderson and Paris Hilton illustrate the willingness of a generation of women to ply themselves into camera-friendly sex objects. Much too much scandal was made out of the Janet Jackson Super Bowl exploit, but few people seemed to object to its most insidious aspect -- not the baring of a nipple, but the pantomime of sexual aggression without reprisal: a man rips off a woman's clothes, she pulls a funny face and keeps on singing. And as far as violence goes, it's interesting that women are now victimized not only by men but, with statistically increased frequency, by other women. The Glenbrook North High School hazing incident, featuring junior-class girls forced to sit while drunken senior girls doused them in feces, urine, paint, animal guts and blood, followed by punching and kicking -- much of which captured in yet another infamous video -- was a chilling example of this trend.

This is the sad state of affairs that is, to the Islamic mind, the dark side of our much-touted freedom. And it is exactly this dark side that we are rubbing their nose in. The torture at Abu Ghraib says: Our pornography will conquer you.

In contrast, Islamic terrorists divulged the recording of a bloody execution. The victim, an American civilian: a sacrificial lamb whose blood was spilled with the declared intention to restore Arab pride. This is, as much as ever, a war of symbols, and the symbol of Arab emasculation couldn't but inspire somebody to create a symbol of absolute and terrifying Arab supremacy over a Western man. The American government reacted with proclamations of horror for such barbarity. But such barbarity is a direct reflection of our own dehumanizing ways. A beheading (a 40-second beheading with a knife) undoubtedly represents a more extreme form of cruelty than to strip somebody naked, beat him, sexually humiliate him and put him on a leash. Yet one has to wonder how much further the American soldiers would have gone if not for fear of disciplinary consequences -- something the terrorists don't have to worry about. If you ever saw "Salo," Pasolini's allegory about the last days of fascism in Italy, you know his thesis that separating the exercise of power from the fear of consequences -- whether because of granted impunity, or because of already certain doom -- is the true test of one's nature. The power of an individual over another will naturally tend to speak the language of sexual sadism, a language that articulates and celebrates it. Sadism will be implicit in every situation of captivity. It will be explicit in situations where the fear of consequences is reduced. It may become extreme where such fear is removed altogether.

It may seem ironic that a war fought in the name of principles and imbued with religious ardor should degenerate to such sordid lows. While in America people flock to see Christ tortured, in Iraq we torture our own prisoners -- for information, for deterrence, but also -- as the pictures document -- for the sheer fun of it. And yet, perhaps "irony" is not quite the right concept. Perhaps the relationship between a U.S.-made blockbuster about Christ's pain and the pain inflicted by our soldiers abroad is closer and more inevitable that the notion of "irony" would suggest, because many of the torturers are no doubt heartland Americans, many of them surely devout Christians -- the core audience of "The Passion of Christ." They are the people Bush directly addressed when he characterized the war as a crusade, a fight against evil in the name of the God. The aptitude of Christians for delivering pain draws on a rich, millennial tradition -- a tradition built on certainty and a Manichean worldview. The ability to torture somebody both requires and confirms this certainty; the torturer's exhilarating privilege is to feel right by God while doing what is normally forbidden.

"The Passion of the Christ" is, not unlike an exploitation movie from the '70s, saturated with ultra-violence to the point of ridiculousness. Yet the representation of this violence is unobjectionable to the audience because the violence is inflicted upon the Christ. There seems to be no limit to the amount of violence you could show in this context (provided you could root it in the Scriptures). The torturers themselves are not the ultimate culprits: those are the Jews, as architects of the deicide. By assigning blame to "them," we can watch an hour of torture entirely guilt-free. In fact, the more severe the torture, the more godlike and awesome Christ's endurance. Which means we have a moral incentive to welcome the sight of torture, to wish for more and more punishment to be administered and exhibited on screen. The amount of butchery is directly proportional evidence of our own worth: look what Jesus, the extreme athlete of pain, chose to endure in order to save us! This is the fundamental perversion of the movie -- that it encourages us to fetishize and get high on the horror of the martyrdom.

Sacrifice is perhaps the most ancient form of religious devotion. It goes back to pagan times, when it was meant to placate the gods. It is at the heart of our notion of justice, which focuses its previously random nature onto a "culprit" whose death will placate the aggrieved party. Christian sacrifice is rather meant to educate. It comes as the culminating point of a vast body of teachings. By choosing to emphasize the sacrifice outside the context of those teachings, Christianity (Mel Gibson's version of it) harks back to the most primitive, bloodiest aspect of religiosity. "The Passion of the Christ" repositions pain, blood, sacrifice, at the heart of the religious experience.

Why is this exercise so relevant and so powerful right now? The answer takes us straight to 9/11. As much as we loathed the terrorists, we couldn't help being affected by their conviction. When Bill Maher disputed the assertion that they were cowards, the hysterical outrage that met his remark was a symptom of a raw nerve being tweaked. Because this kind of conviction is precisely what we couldn't be further from. The question is not whether their conviction justifies their action -- it doesn't (and I tend to believe a case for the fundamental cowardice of attacking any defenseless person, regardless of whether or not one commits suicide in the process, could be convincingly made.) The question is how we respond to the sheer intensity of the conviction. Because as much as this intensity horrifies us, it may also be something that, in some dark recesses of our psyche, we (some of us, anyway) envy. And so we may want to remind ourselves that our own God performed the ultimate act of self-abnegation, exonerating us from doing the same as long as we maintain and worship the memory of it. You can fly into the building in the name of Allah? We can reenact the torture and crucifixion of Jesus Christ in the name of our own God. The effort to distill every ounce of sacrificial pain from this representation, and the uplift that the audience gets from it, can be read as a response to the suicidal fury of the 9/11 terrorists. Our guy's sacrifice was not only purer, because he didn't bring any innocents along for the death trip, but it was also more painful. We can reach back into our spiritual history and find our own, superior certitude .

It's not simply demagogy that the war against terrorism, or against Iraq, has been cast in religious terms, as a crusade, a fight against evil and for God-given freedom. Sept. 11 shook us to the core because if an act like that can be executed not in the name of profit, power or the traditional motivations we understand, but in the name of religious ideals (however aberrant), our own beliefs -- or lack of them -- are called into question. We suddenly realize we live in a spiritual vacuum, where no comparable degree of conviction can be easily summoned forth.

"The Passion" came to fill this profound need. Paradoxically, the fervor it inspires is directly proportional to the distance we have accrued from any kind of spiritual authenticity in our life. The more our culture obsesses about fad diets, plastic surgery, Paris Hilton's sex video, Donald Trump's hair or Jennifer Lopez's butt, the more fervent our response to "The Passion" has to be.

And so we come full circle. While frivolousness and pornography saturate our culture, "The Passion" offers us redemption, all the more effectively for pushing the limits of graphic representation that porn itself has irrevocably stretched. And while at home we feast our eyes on the torture inflicted upon the Christ, abroad we vindicate ourselves by torturing the infidel with the same righteous abandon, in the way we know best -- a pornographic way. Two faces of torture. Two faces of porn.

Shares