"I believe in larceny. Homicide is against my principles."

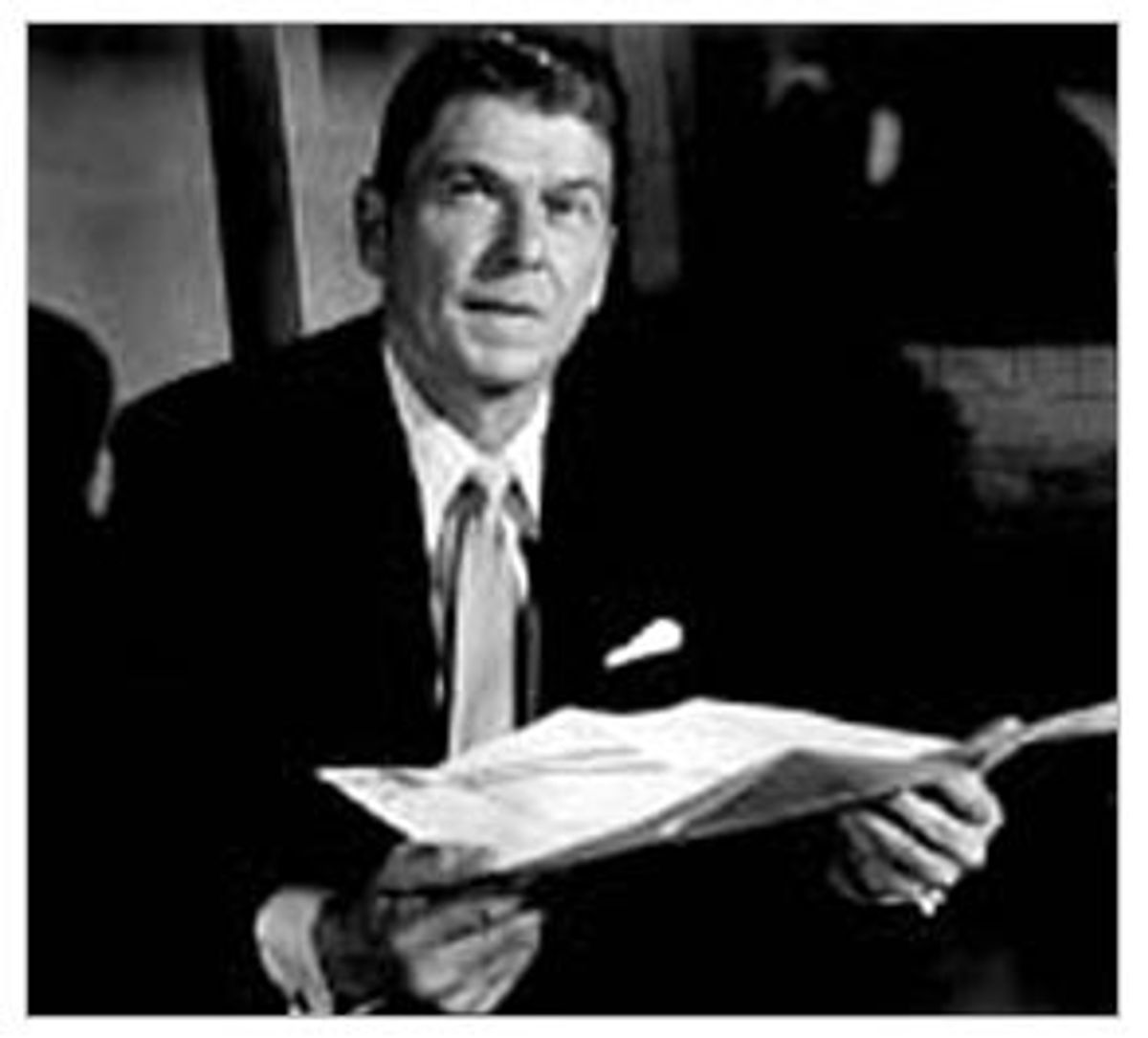

That's Ronald Reagan speaking, in his last film role as mobster Jack Browning in Don Siegel's 1964 "The Killers." It was the only time Reagan ever played a heavy, and according to costar Clu Gulager, he despised the film. "Ronnie is a nice man," Gulager quickly adds.

A nice man would despise this movie (made for NBC and then released in theaters after the network turned it down for being too violent). Cold, mean and unrelievedly brutal, "The Killers" radiates cynicism and contempt and cruddiness. It's a movie that opens with blind people being slapped around by a pair of hit men (Lee Marvin and Gulager who, in a touch that feels like a sick joke, wear dark glasses) and ends with every major character dead. Forty years later, it also works as a prophetic shadow history of Ronald Reagan's political career and the America that career brought forth. "The Killers'" window on Reagan's dark side may be the best antidote to the Reagan hagiography.

Over the course of "The Killers," the idea of watching Ronald Reagan as a brutal mob boss seems at first a thrilling act of self-desecration on Reagan's part; by the end of the movie, it seems perfectly reasonable. Throughout the movie, the familiar and predictable break free of their moorings. You feel as if you should be able to dismiss it as just another cheesy gangster movie. And yet its sordidness adds up. By the early '60s, the classical Hollywood studio filmmaking of the '30s and '40s had become mummified. Made on the cheap at Universal (as nearly everything at the studio was then), "The Killers" reeks of that calcification. There isn't a breath of fresh air or reality in "The Killers." The movie is filled with obviously phony rear projection and cardboard sets that can't convince you for a second that you're seeing real streets, hospital rooms, hotels, flophouses. No place in this movie seems like anywhere that anyone real could actually exist. And Universal's notoriously cheap color processing renders everything washed-out, sickly, flat.

In other words, its relation to the Hollywood films that had preceded it is exactly the relation of Reagan's white-picket-fence vision of America to the real thing -- a false, shallow copy stripped (thanks to Don Siegel's brutally efficient direction) to its basest motives. The movie may be shallow, but it's not dead. In fact, it's obscenely alive. Like the America Ronald Reagan would bring about, this is a place where ruthlessness is business as usual, and the line between enterprise and thuggishness has blurred. By the end of the film Reagan's Jack Browning is heading his own development corporation. Essentially, he's still in the same business. But if a Contra can become a "freedom fighter," a hood can become a respectable businessman. "Somewhere in California," is how one of Browning's flunkies answers Marvin and Gulager's hit men when bullied to reveal his boss's whereabouts. It's as if Browning had simply disappeared into the Golden State, the way the man who plays him nearly had.

The year "The Killers" came out, Ronald Reagan was a 53-year-old has-been B-movie actor, the former host of "Death Valley Days," a G.E. spokesman, and a speaker touring the country warning of government intrusion into the private sector. But like Browning, Reagan had another career waiting. In October of 1964 he made a nationally televised speech in support of Barry Goldwater. The speech didn't help Goldwater's trouncing at the hands of LBJ, but it brought Reagan to the attention of a group of conservatives who supported him for governor of California in 1966, a post he held for two terms and the platform for his entree into national politics, a stage on which he would make the extremism of Goldwater the mainstream of American politics.

Ronald Reagan, we are being told by newspapers and television and endless pundits, made America feel good about itself again; he washed away the self-loathing of Vietnam and Watergate and the "malaise" of the Carter years, and allowed Americans to stand tall once more. They never mention his divisiveness, though it was evident in a clip that somehow slipped through the network's nonstop wreath-laying last weekend. In 1967, then-Gov. Reagan tells a crowd about being picketed by a group of young people holding signs that said, "Make Love Not War." The problem, Reagan tells his listeners, is that they appeared capable of neither. This was shown as an example of Reagan's ability to charm an audience with his quick wit, even though he essentially was saying: "Those antiwar fairies can't fuck any better than they can fight."

"America is back," Reagan had said. But where had it gone? To believe in Reagan's proclamation, you had to believe that "America" had gone missing in the years preceding his ascent. You had to believe that an America that allowed for dissent -- that is to say, the very practice of democracy itself -- was not really America. And it wasn't just dissent that was un-American -- it was the regulations on corporations that Reagan had long railed against, the assumption that government had a basic responsibility to aid its citizens.

"America" under Reagan elevated to the realm of pure construct. It became a notion that floated free of not just Americans themselves, the majority of whom grew poorer while a select few grew vastly wealthier. It floated free of the effect of Reagan's policies and the meaning of his words. In his second term he said, "We must never again abuse the trust of working men and women by spending their earnings on a futile chase after the spiraling demands of a bloated federal establishment." And so the earnings of workingmen and -women were no longer spent on the very laws and programs that had allowed them job protection, health insurance, care for their elderly parents and education for their kids. Three hundred thousand people lost Social Security disability benefits in his first term alone.

And finally, Reagan's vision of America floated free of reality itself. Denying that he had exchanged arms for hostages in 1987, Reagan said, in the quote most characteristic of his presidency, "My heart and my best intentions still tell me that is true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not."

Whether you consider that a supreme calculation or the guilelessness of an amiable dunce, it demonstrates Reagan's ability to define reality not by the facts but by what he claimed his intentions were, by the image rather than the substance.

Nothing really damaged Reagan's nice guy image; nothing dirtied his hands. That's why at the end of "The Killers" it's supremely satisfying to watch Lee Marvin's blood leaking over the nice upper-middle-class California suburban home in which Reagan's Jack Browning has taken refuge. Reagan was not stained by the blood of those killed by the "freedom fighters" in Central America or the people who died of AIDS in this country because he ignored the disease.

Reagan's legacy makes it easy, watching "The Killers," to believe in the ruthlessness of his character. Jack Browning seems the dark face of the Gipper; certainly he's the true face of the politicians who followed in Reagan's footsteps -- Dick Armey, Newt Gingrich, Tom DeLay, Trent Lott, George W. Bush, et al. -- not one of whom has ever been able to sell himself believably as a likable guy. Reagan's truest legacy will be as an affable advance man for the thugs who came after him.

Shares