Free association: drugs.

What comes to mind?

Getting high in your dorm room after finals? John Belushi in a hotel room, slumped over from a deadly mix of coke and heroin? A drive-by in South Central Los Angeles? A messy group hug at a warehouse rave? Medical marijuana? Mandatory minimums?

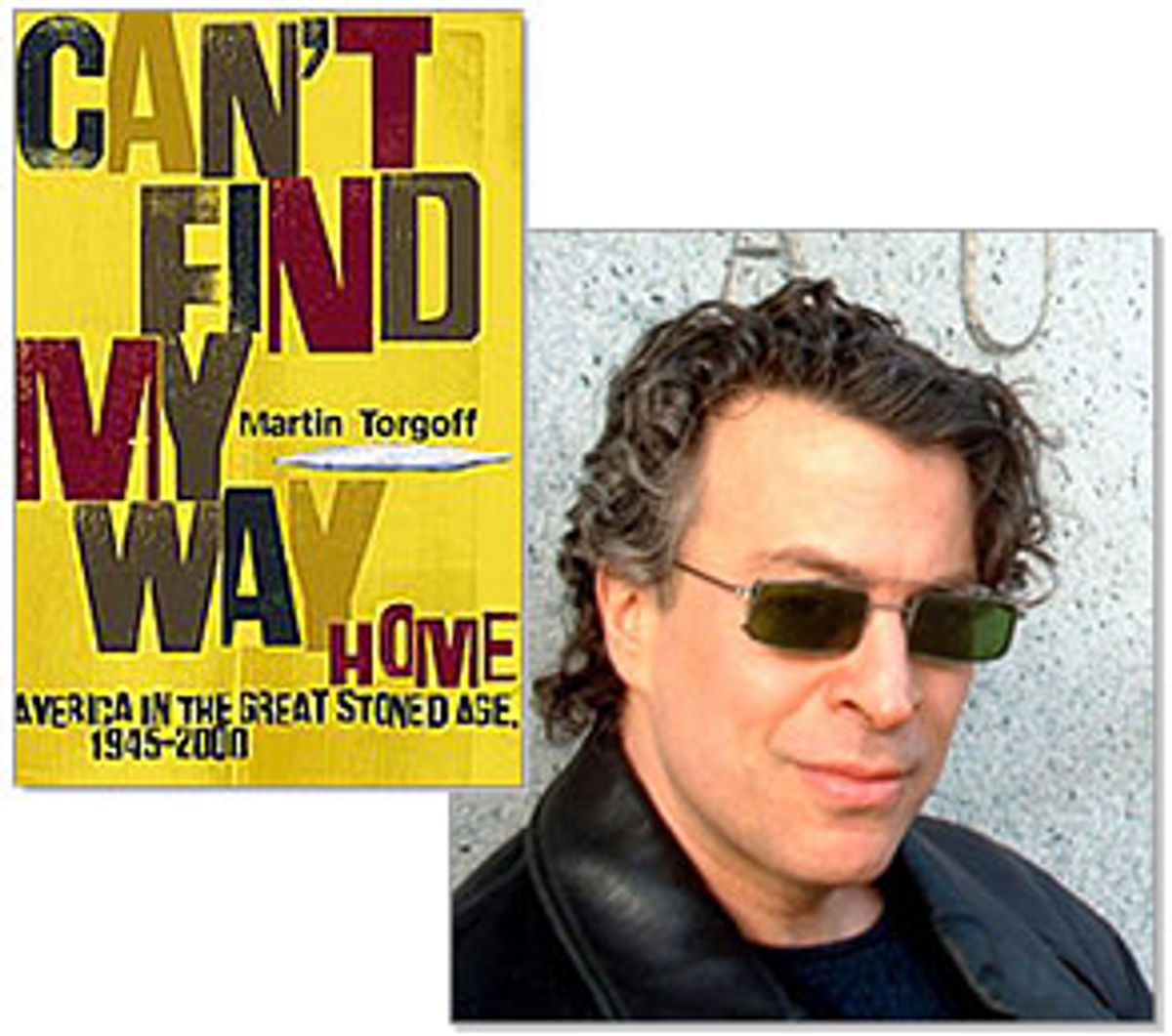

In "Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945-2000," Martin Torgoff argues that the story of drugs in America is all these images and ideas -- and much, much more. Mixing oral history, autobiography and a large dose of firsthand sources from High Times to Foreign Policy, the book moves across time and culture, starring one drug after another, from marijuana to MDMA.

Torgoff, 51, a New York journalist and biographer of Elvis and John Cougar Mellencamp, refers to his own drug use and abuse throughout the book. Now married with a baby, Torgoff started smoking pot at 16 in 1968 -- the night Nixon was elected president. "I remember because as I was getting stoned, I heard the election returns coming down through the ceiling," he says. "That was the beginning of my run." It was a run that would take him from pot to psychedelics to coke and alcohol -- and finally into recovery at 37, in 1989.

Besides using his own story, he fuels the book with a polyphonic spree of supporting characters, among them storied beats Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac; psychedelic superheroes Timothy Leary and Terence McKenna; fallen jazz great Charlie Parker; tragic rock stars Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison; cult figures Ram Dass and Wavy Gravy. The result is a sweeping epic that bounces between orgiastic nostalgia trip and cautionary tale -- and, at times, like the drugs themselves, can assault the senses.

Torgoff spoke with Salon about his own decade-long journey researching and writing "Can't Find My Way Home," the polarizing pull of drug laws, and the discoveries each generation makes by lighting up.

Drug stories aren't rare in the card catalog of America literature. Why write your book?

When my friends and I first starting doing drugs in the late '60s, we were making not just a statement about the experience of the substance, but a statement about lifestyle, politics, spiritual values, communitarian values. If you smoked marijuana, you were against the war in Vietnam, and you listened to a certain kind of music -- the psychedelic music, the Beatles. But it also had to do with a life philosophy. In the beginning it was all about opening to things -- to yourself, to the world of the senses, a kind of creative potential. It made you see and feel things differently. There was a philosophy around it of peace and brotherhood -- all the clichés.

But by 1973, suddenly the pharmacopoeia opened wide. Although most of us had tried coke before we left school, it really hit the scene by '77-'78, and followed us right into the arena of work and careers as we got older and had more discretionary income. The values it promulgated were antithetical to pot and psychedelics -- you'd never think of staying up three days in a row smoking weed. It became the preferred substance of lawyers and stockbrokers, and that pretty much sums it up. It promoted an ego-driven culture of greed, exclusion, conspicuous consumption and corruption. Perhaps the closest thing to a Republican drug of choice.

When I stopped doing drugs in 1989, I had a tangled web of feelings about them. I was uncomfortable with recreational drug use, but also equally uncomfortable with the creed of abstinence. And then I was uncomfortable with the "be smart don't start" anti-drug phenomenon. I wanted to go back to the sources to see how all the attitudes about drugs -- both for and against -- formed in this country. I wanted to know how we went from marijuana and psychedelics, drugs that opened things and appealed to your senses -- to coke and Quaaludes, drugs that numbed you and were really about ego, in which your pleasure centers lie to you and tell you that you're experiencing pleasure. I wanted to understand how all of this affected my life, my generation, and the whole culture at large.

There's a lot of wisdom accrued over generations that hasn't been passed on. I call it the "Temple of Accumulated Error" in the book, which is a phrase I ripped off directly from my friend Wavy Gravy. There are several generations now that have amassed significant life experience with illicit substances -- underground folk wisdom about what they really do, how they can help us, how they can distort and damage us. I think our culture has far more to learn from people who have actually taken drugs than from those making and enforcing the policies that prohibit them. And I'm talking about everyone from the most horrific addicts to the most responsible kind of casual users, and everything in between. To me it's a no-brainer. Bill Bennett can't teach you anything about drugs, except to tell you that you're a bad person for using them.

Your book journeys from the beats smoking dope all the way to the ravers taking Ecstasy. The transitions from one drug to the next in culture make a lot of sense. So do you buy the so-called gateway theory?

Nixon always said it: "Marijuana is a halfway house to something else." Of course, that something else was supposed to be heroin, and since the 1950s that's what parents had been telling their children. I don't think anyone would deny that there are a large number of heroin addicts who started out on marijuana, so in that sense it's true, but it's also true that a lot started out on alcohol and nobody is calling that a gateway drug. But here's the big picture of it: 60 to 70 million Americans have admitted to trying an illegal drug at one time or another, almost one in four. Given that some 20- to 30 million of them were regularly smoking pot at one time, and given that there were never any more than between 300,000 to 700,000 heroin addicts (a very high estimate) at any given time, just do the math. Even if all of those heroin addicts actually did start out uniquely with marijuana, it's a small percentage. In fact the gateway theory is a perfect example of what U.C.-Santa Cruz sociologist Craig Reinarman calls "the routinization of caricature": how we take worst-case scenarios and anecdotes about drugs and make them seem routine, part of an "epidemic."

Hence, the drug laws.

I think drug enforcement is the closest thing this country has ever come to actual fascism. When I look at the erosion of civil liberties that gained speed in the '80s, I see tremendous injustice. It's been a long time now since the actual facts mattered about drugs in this country. You tell the same lie over and over again for so many years and fewer and fewer people will be apt to stand up and say: "This is a big lie."

And that big lie is?

The big lie is that all these drugs are the same and should all be classified as one sort of evil. We have 60 million Christian conservatives in this country, the most activist wing of the conservative party, who truly believe all drugs are the tools of Satan.

If we really don't start talking about drugs honestly, we're never going to get anywhere with drug policy reform in this country. The right wing likes all drugs to be lumped into evil substances, with no differences among them.

What were the most memorable moments in the decade you spent working on "Can't Find My Way Home?"

Two moments stand out in particular: I had a wonderful conversation with Ram Dass that really brought the psychedelic experience to life. It gave me such insight into the excitement that these guys felt. They felt it could reengineer human behavior and thought and literally remake society. They thought they could use it to access mystical experience and wisdom, be used as a spiritual tool to provide conscious and tangible contact with the Godhead. They really did believe that they were on the verge of something as revolutionary as the papers of Sigmund Freud.

The other time that comes to mind is standing on the front porch of Silvia Nunn's home in South Central L.A. Sylvia Nunn blew my mind. A 30-year-old Blood deep into rock cocaine -- she was an example of a full lifetime in the gang culture. She spoke with an honesty and truth about her life that was both chilling and moving -- drugs, homicide, getting shot, suicide attempts, the deaths of family members, the vicious cycle of drugs and crime and vengeance -- and how desperate she was to escape it. She broke my heart, and it was her humanity that did it -- this wasn't some media caricature of a gang-banger but a gifted person with incredible intelligence, heart and goodness -- who was obviously trapped in the life. The whole reality of her life was brought home one night when we were chatting on the front porch of her family's home around sunset and she casually informed me that it was "drive-by time" -- her way of telling me that I could die at that very moment just by being there on the porch with her.

What parts of drug history have been well documented in the last 60 years and which haven't?

The media coverage of drugs in this country has been pitiful. The phrase I use is "sensationalized superficiality," since the coverage suffers from both of those things and has since the 1930s. Still, for every aspect of drug culture since World War II, there have been a small handful of works that have rendered it powerfully. Dizzy Gillespie's autobiography "To Be or Not to Bop" about his relationship with Charlie Parker and what was going on in the black community with drugs at that point, and Claude Brown's "Manchild in the Promised Land" were tremendous tools for me.

The psychedelic era has been the best covered. There was a time in the late '60s when some young knowledgeable journalists starting writing about both drugs and culture -- a whole crop of people at Rolling Stone who could write about drugs and culture from real experience -- David Dalton, David Felton, Joe Ezsterhas, Greil Marcus, Hunter S. Thompson. Then there have been lesser-known works like Marco Vassi's "The Stoned Apocalypse" -- it's an amazing glimpse at how the psychedelic culture evolved into a strange sexual spiritual New Age cult on the West Coast. Once you come to the end of the '60s and '70s, the cocaine and Studio 54 era, it gets spotty.

Lenny Bruce believed that pot would be legal because of all the law students smoking pot in the '60s. Law students still smoke weed, but marijuana is still illegal. What happened?

Somewhere along the line the left abandoned the drug issue. They had to, since they were so vulnerable, as it was with the right-wing critique of the welfare state and liberal approach to the Cold War. By the 1980s, with coke and crack, drug culture was getting very toxic. So the Democrats were extremely vulnerable about drugs and jettisoned the whole progressive drug policy -- they gave up on harm reduction, education and decriminalization -- and marched in lock step with Republicans in the drug war. And the right wing was able to exploit it masterfully. There's no more crystal-clear example of the revenge of the right wing for the 1960s than the drug war.

During the famous 1967 Be-In, Allen Ginsberg looked out at 30,000 tripping people and whispered to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, "What if we're all wrong?" Do you look at some of the drug cultures today and wonder the same thing?

The answer to that question probably won't become apparent for another three to five years when you guys have come out the other end and really start digesting the experiences you've gone through. For many of us who took psychedelics back in the '60s and '70s, it was like being in a whirlwind, and we didn't get real perspective into the glories and follies of our experiences until years later, when we could look back much more objectively on how they may have changed us or changed the culture.

When you first did drugs with your friends, you write, "We thought we could solve the ancient and infinitely complex mysteries of man and his place in the universe simply by lighting up a joint and listening to the Beatles." Does every generation need its own version of that scene?

Every generation wants that experience, and I don't know that that's going to stop. One of things that's the ultimate folly of the whole agenda of prohibition is this idea that drug use can be unlearned by culture -- that it can be eradicated. It's now deeply embedded in the cultural psychology of this country.

There's something to be said about how that generation in the '90s was trying to find its own identity, to write its own story when it came to drugs. There was a continuum that went from psychedelic culture of the '60s to the MDMA culture of the '90s. It had to do with mostly the different nature of the substances. LSD was a wild roller coaster ride -- like ripping your soul out and throwing it down on the kitchen table and staring at it for six hours in its bloodiest state.

Ecstasy is a totally different thing, but it had a value and power in shaping the sensibility of a generation. It was the antithesis of the self-interested cocaine culture of the '80s. For one thing, it was about being with other people and really empathizing with them. The thing that always struck me about the raves were the love-flushed faces and beatific grins, and the hugging and affirmation between people. Except for certain dimensions of the recovery self-help culture, I really hadn't seen anything like that since the be-ins and happenings of my youth. And then when I heard the tenets of the rave movement -- Peace, Love, Unity and Respect -- I began to realize that there was something going on that was much greater than just people taking drugs.

When the parts of the hip-hop community embrace marijuana as a peaceful alternative to crack, you get the feeling we've come full circle from the time of the jazz hipsters getting high.

That's why the whole cannabis aspect of hip-hop has been really interesting to see. The war on drugs was really a war on marijuana. The result was suddenly marijuana was like $200, $300, even $400 an ounce -- and that's not affordable for kids in the ghetto. If pot was decriminalized and made affordable, would people still use meth, a drug which is so fucking bad for you? Sure. But I just can't believe it would be the same problem. The question is: Are you going to allow them substances that are more benign?

Would the war on drugs have happened without Reagan?

Yes, but not in the same way. There have been anti-drug zealots since Harry Anslinger, but Reagan was a unique figurehead -- and let's not forget Nancy. He came to Washington convinced that his election gave him the mandate to roll back drug use right along with communism and the size of the federal government. And I don't think anyone was as capable as Reagan of exploiting the drug war for political gain. He likened the drug war to the American crusade of the Second World War! Think of it: equating those who smoked some pot with the evils of fascism. Reagan led the charge, but he was followed by a whole cadre of true believers, from Ed Meese to Rudy Giuliani. But it all reached an ideological crescendo with Bennett. If Reagan was the figurehead, I consider Bennett the Torquemada of the drug war -- its Grand Inquisitor. There was an element of harsh cultural vengeance in Bennett's reign as drug czar against the whole legacy of the 1960s and 1970s that was unparalleled. He was another unique character -- as singular in his own way as Kesey or Leary -- and very much a counter-reaction to them.

Ethan Nadelmann of the Drug Policy Alliance says that the War on Drugs has been founded on myths, fears, exaggerations and lies. Can it be repaired?

Unfortunately, I don't think it can in our lifetime. Drugs are still too polarized for people to look at them rationally. They need to be denuded of all of the cultural associations of the last 50 years. We really need to look at how people use them, abuse them, how they've changed the country, and what can be done. It may be that we have to wait until this generation that lived through the explosive time of the '60s and '70s -- when drugs use went from a tiny fraction of the country to one in four -- are dead to really look at this issue differently.

Any kind of reform will be marginal, incremental and certainly hard-fought. Look at how slowly the overturning of the Rockefeller laws is going. There's no one who wants to get up on the floor of Congress and say that punishing first-time, nonviolent offenders this harshly is barbaric. Nadelmann says that nothing will happen until Republicans start to see the wisdom of reform in ways that work with their sensibility. It won't be the Jerry Browns and Mario Cuomos that get the drug laws reformed. It's the George Shultzes coming out and saying he's for decriminalization and other changes that will lead to drug law reform in America.

What will you tell your son about drugs when he gets older?

I will tell him that I prefer him to not smoke pot until he's out of high school. His brain is still growing, for one, and there are aspects of marijuana and adolescent life that are problematic. I smoked pot when I was 16 for the first time and it rocked my world. So I will try to instill a sense of humility and respect for how powerful this stuff can be, which is what we sort of blithely disregarded.

Drugs can change you a lot. There are things about a change of perception that are miraculous, and that's an enormously powerful thing. I'd try to teach him that drugs have aspects that are entirely useful, but also can be extremely damaging. Will I be happy if he goes against me? No, I won't. But I won't be surprised.

I'm someone who went down the path of recovery, yet am a libertarian about drugs. I was both helped and harmed by them. I didn't want to romanticize drugs with this book, and I just as certainly didn't want to demonize them. I just wanted to tell the truth about them as clearly and as nonjudgmentally as possible.

Shares