Last September, Paul Wolfowitz was the special guest at a memorial service in Arlington, Va., for an influential Shiite cleric killed in a car bombing in Najaf, Iraq. The deputy defense secretary hailed Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim as a "true Iraqi patriot," and he quoted from the Gettysburg Address as he likened the slain leader to the Union soldiers who had died to preserve their country. It was a eulogy that al-Hakim undoubtedly would have found jarring. His Islamist political party, the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, and its 15,000-man militia had been funded by Iran, a member of President Bush's "axis of evil." And al-Hakim himself had long been wary of perceived American imperialism in the Middle East, even as his party, known as SCIRI (pronounced "SEA-ree"), cooperated with the Coalition Provisional Authority on the transfer to Iraqi sovereignty -- the likely reason he was targeted for assassination.

As symbolism goes, the memorial service served to highlight the tangled politics in post-Saddam Iraq, where idealized notions of "friend" and "foe" have dissolved into a murkier reality. Once, Pentagon war planners like Wolfowitz envisioned the toppling of Saddam Hussein with clarity, predicting that the long-suppressed Shiite majority in Iraq would greet Americans as liberators and that democracy would naturally flower. But clarity has been washed away by images of charred American bodies swinging from bridges and naked Iraqi prisoners on dog leashes. Yet to emerge is a clear outline of a new Iraq, which has been tugged in opposite directions by official enemies -- Iran and the United States -- that happen to have shared a common interest in Saddam's removal.

As the largest mainstream Shiite party, SCIRI is an important player in Iraq's future, but one with an ambivalent history with the United States. It was one of the opposition groups that the United States counted on to help bring down Saddam. Yet SCIRI is also a vehicle in which Iran has invested heavily in a bid for influence in post-Saddam Iraq. And so despite Wolfowitz's hailing of the slain Ayatollah al-Hakim as a kind of Shiite Abraham Lincoln, it is far from clear that his Islamist party, which supports an Iraqi government run according to Islamic principles, will help build the kind of secular democracy that the United States said it hoped to leave behind in Iraq. It is likely that the new Iraqi constitution will be influenced in some manner by Islamic principles, but it's anybody's guess whether a sovereign Iraq -- assuming it stays united -- will look more like a secular Turkey, a cleric-run Iran or something in between. There are too many competing motives and agendas to predict any outcome with certainty, no matter what face U.S. policymakers put on it.

The blurring of Iranian, American and Iraqi interests came into sharp relief last month when Iraqi and American forces raided the Baghdad home and offices of Iraqi National Congress leader Ahmad Chalabi on suspicion that the one-time Pentagon favorite had betrayed U.S. secrets to Iran. It was a confusing turn of events, made even more perplexing by the fact that Chalabi, a Shiite, had worked openly with Iranians for many years, most prominently through his contacts with SCIRI, which was known to be an arm of Iranian intelligence. In fact, SCIRI was active in Chalabi's INC from 1992 through 1996 and was named in the 1998 Iraqi Liberation Act, signed into law by President Clinton, as one of the opposition groups that the United States should work with to topple Saddam.

It was thus no secret that Chalabi had a relationship with Iranian intelligence. But the salient question quickly became: Which American official was so stupid as to tell the INC leader that the United States had broken Iran's secret communications code, information that U.S. intelligence said Chalabi then passed on to Iran? Chalabi had long been an informal conduit between the United States and Iran, which have not had formal diplomatic relations since American hostages were seized in the 1979 Islamic revolution. Through SCIRI, the United States kept a back door to Tehran propped open. Had that game now gone awry?

SCIRI was founded in 1980, at the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war, by Iraqi Shiite clerics who sought a haven from oppression by Saddam with fellow Shiites in neighboring Iran. But the relationship was controversial from the beginning, according to Imam Mustafa al-Qazwini, an Iraqi-born Shiite in Los Angeles whose father was a founder of SCIRI.

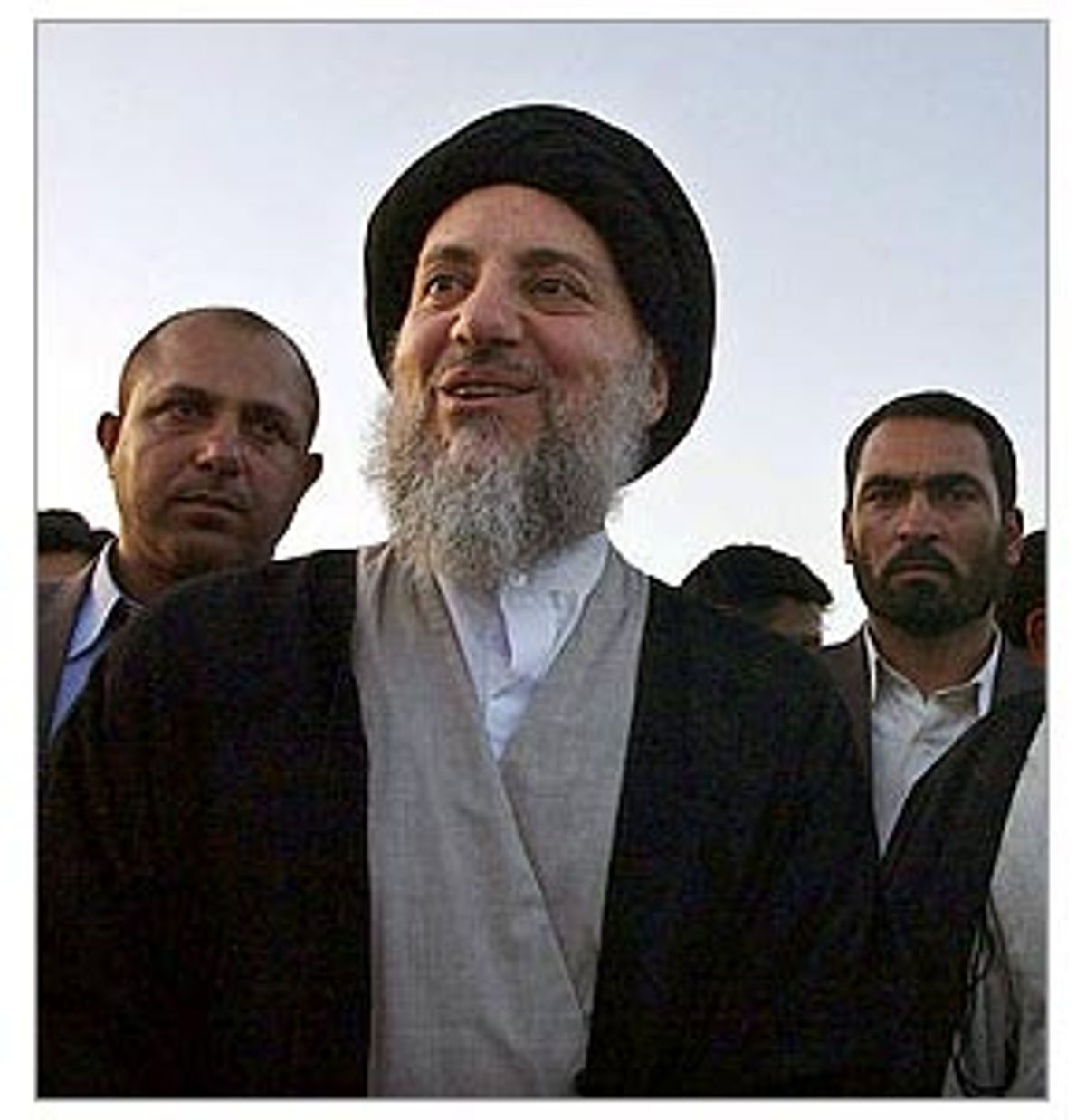

A handsome 42-year-old with a neatly trimmed, graying beard, al-Qazwini wears a black turban, symbolizing his family's descent from the prophet Mohammed. A naturalized U.S. citizen, he speaks fluent, colloquial English. We met earlier this month at a Washington conference of the Universal Muslim Association of America, an organization of politically active American Shiite Muslims.

His father, Ayatollah Mortada al-Qazwini, broke with SCIRI's al-Hakim soon after the group's founding amid a dispute about its alliance with Iran, al-Qazwini told me. His father believed that Iraqi Shiites would be better served by leaders who remained independent of foreign governments -- Iranian or American. In the mid-1980s, the Qazwini clan left Iran for the United States and its open political system. The elder al-Qazwini returned to Iraq last year, settling in Karbala, and, in the model of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, remains aloof from politics in the belief that clergy should not play a direct role in governance, his son told me.

Al-Qazwini said that he and his father have rebuffed overtures from the U.S. State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency over the years because they did not want to align themselves with any foreign governments. "I always feel, if you can work freely from these governments you should," al-Qazwini said. "Generally Iraqis don't like the idea of dependence. Once someone is seen as collaborating with a foreign government, they might not be as trusted." That has been a problem to varying degrees for both Chalabi and SCIRI in Iraq, he added.

Still, SCIRI, now led by Ayatollah al-Hakim's younger brother, Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, retains significant clout as the best organized Shiite party, in part because of the support it had from Iran. SCIRI is believed to have taken from Iran an amount similar to the more than $30 million Chalabi's INC accepted in U.S. funding before being abruptly cut off last month. And despite its quasi-official relationship with the United States, SCIRI mostly kept the Great Satan at arm's length. Until 2002, most contacts with the United States were made informally through Chalabi and Kurdish representatives, according to SCIRI's U.S.-based representative, Karim Khutar al-Musawi, who told me about the group over coffee recently in Washington's Mayflower Hotel.

Aside from acting as a kind of liaison between the United States and Iran, in the mid-'90s SCIRI agents also worked openly with Chalabi in northern Iraq on operations to undermine Saddam. Chalabi was then working for the CIA, whose small team in northern Iraq was headed by former CIA operative Bob Baer. "SCIRI was never under any sort of Western supervision or control. They did exactly what they wanted. And they reported to Tehran," Baer told me.

As an American agent, Baer was keen to learn all he could about Iran. Chalabi invited him to meet his contacts in Tehran, but Baer had to decline. "I would have been happy to, but that was a firing offense. The State Department would have gone nuts," he said. But there was no restriction on meeting with SCIRI, which, after all, was part of the American-backed Iraqi National Congress. So, Baer said, he talked often with SCIRI agents in northern Iraq, where the Americans and Iranians shared a common enemy in Saddam Hussein.

A master manipulator, Chalabi frequently played Iranian and American intelligence off each other, Baer said. The most serious stunt occurred in February 1995, when Chalabi was gathering support for an uprising against Saddam. The Americans were noncommittal and, among other moves, the INC leader went fishing for Iranian support. He forged a letter from America's National Security Council that appeared to direct him to assassinate Saddam, then left it on his desk for Iranian intelligence agents to read, hoping the disinformation would convince the Iranians that the United States was serious about toppling Saddam, Baer said. "He was being very practical about this. He needed the Iranians to think the plan would go through so they would let loose with the Badr Brigades," the armed wing of SCIRI.

Chalabi's uprising, and a parallel coup planned by Sunni Iraqi military officers inside Iraq, collapsed amid betrayals by the Kurds and continued ambivalence from Washington. The debacle caused both the CIA and SCIRI to part ways with Chalabi in 1996. But by 2002, when it looked as if President Bush was serious about toppling Saddam, SCIRI began sniffing around again. Its representative, al-Musawi, set up shop in Washington. And in August 2002, SCIRI logged its first formal contact with the United States when Ayatollah al-Hakim's younger brother, Abdul, traveled to Washington as its representative for a pre-war round of meetings with Bush administration officials.

Al-Hakim and other Iraqi opposition figures met with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of State Colin Powell and (via satellite hookup) Vice President Dick Cheney, al-Musawi said. Also at the 2002 meetings were Chalabi, Iyad Allawi -- the recently named interim prime minister of Iraq, who has longtime ties to the CIA -- and two Kurdish representatives, Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani.

"This was the first official contact for SCIRI, because before we did not automatically believe in the American direction -- whether they meant it or not," al-Musawi said, referring to the United States' historical ambivalence toward removing Saddam, most prominently its failure to support Kurds and Shiites in their revolt after the Persian Gulf War, which Saddam brutally suppressed.

Graham Fuller, former vice chairman of the National Intelligence Council at the CIA and an expert on Islam, said that the United States must deal with SCIRI, despite America's preference that Iraq have a strictly secular government. Although SCIRI wants Iraq's government to be run according to Islamic principles, that probably does not mean an Iranian-style theocracy, Fuller said. SCIRI's al-Musawi confirmed that view, explaining that the party wants a "kind of separation of church and state" in which clergy would not become politicians or government officials.

Added Fuller of SCIRI: "They are uncomfortable with American goals in the region, and they would see the American policy as hostile, rightly or wrongly, to any Islamic state, however you interpret that ... They're wary of American imperialism in general. But that doesn't mean they weren't willing to cooperate in furthering the greater goal of removing Saddam."

Abdul Aziz al-Hakim became SCIRI's representative on the United States' handpicked Iraqi Governing Council after the March 2003 invasion of Iraq. But when his brother was killed in the car bombing at the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf last August, al-Hakim blamed the United States for creating instability and demanded an end to the occupation. Such positions are part of SCIRI's balancing act, Fuller said. "As the majority, the Shiites are the beneficiary of [any] democracy, so they're willing to cut the United States a lot of slack as long as the U.S. is bringing about the goal of democracy. But once they get to democracy, they want the United States to please leave," he said.

A SCIRI member, Adel Abdul Mahdi, will serve as Iraq's finance minister in the interim government that takes power in Iraq June 30. Mahdi recently declared that the majority Shiites would not stand for limited Kurdish self-rule in the north, setting the stage for a showdown with the Kurds, who have said they will secede from the central government without some guarantee of autonomy.

Shiites, meanwhile, believe that radical Sunni Muslims -- both Iraqis and those newly arrived from other countries -- are targeting their leaders for assassination with suicide bombings in an attempt to drive a wedge between the two sects. What's more, "Al-Qaida is trying to make a war between the Sunni and Shia, to destroy the American project in Iraq and break up the country so the Wahhabis can have influence" with Sunnis, asserted al-Musawi, referring to the strict fundamentalist brand of Islam that is the official state religion in Saudi Arabia.

In that regard Iran, like the United States, also faces uncertainty about its interests in post-Saddam Iraq. A Wahhabi foothold in its next-door neighbor would be an unwelcome development for Iranian Shiites, whom Wahhabis loathe as infidels.

Saddam had kept both Sunni and Shiite religious fervor in check through his authoritarian rule. But now there is no guarantee it can be contained. Looming behind this internal political struggle between religious factions are the two major powers of the Gulf, Saudi Arabia and Iran. The degree to which Iraq might become a chessboard on which they move their pawns remains uncertain.

There are already indications that Wahhabi Islam is taking root in Iraq, worried Shiites say. Al-Qazwini, the Shiite imam from Los Angeles, said that on a recent visit to Baghdad he discovered that the Um al-Tubul mosque had been renamed after 13th century Islamic theologian Taqi al-Din Ibn Taymiyya, an intellectual founder of Saudi Arabia. "There are big signs for the Ibn Taymiyya mosque now. You can see them from the highway," al-Qazwini said.

Fuller thinks it makes sense, with all the countervailing forces in the region, for the United States to deal with all major players, even those that have ties to Iran.

"The United States has slowly come around," he said. "The first Bush administration didn't want to touch the Shia. They were afraid the Shia would take over in Iraq" with an Iranian-style theocracy. But, he added, "I think now the U.S. has learned something about the Shia and their more complex nature. The Shia do not love us, but they are grateful that we threw out Saddam. Now they want us to complete the job and leave."

It remains unclear which legacy will have the most lasting imprint in the new Iraq -- that of Abraham Lincoln or that of the turbaned clerics in Tehran.

Shares