Visitors to Bill Rouverol's apartment may not immediately see, as he does, that the fate of American democracy depends on the gadget sitting by the window.

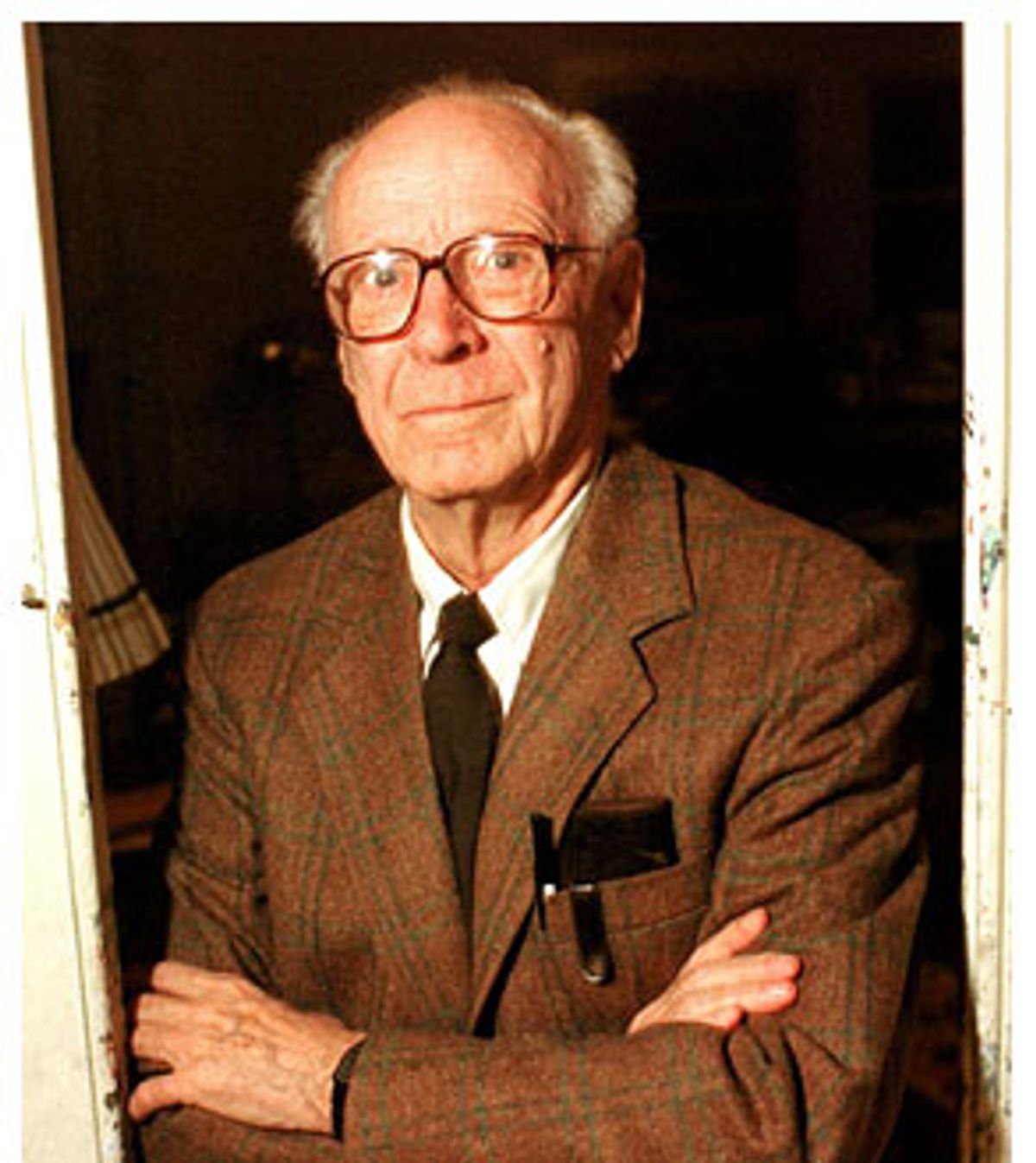

Rouverol, 86, a balding mechanical engineer given to frank words, brown slacks and circuitous journeys of all sorts, has spent much of the last three years designing and building a green plastic box called the VoteSure. With two patents pending, his creation is coming to life in the twilight of a career that has generated more than 100 patents.

The green box is Rouverol's baby, an obsession that has helped wreck his marriage and put him on the trail of elusive county registrars, machinists and patent attorneys. It has driven him to work 10-hour days long after most of his closest friends have passed on, all in a quest to save American elections from the twin dangers of wily hackers and tiny paper squares.

"The whole country is waiting for this machine," Rouverol said. "I think it'll save democracy."

The VoteSure may save Rouverol's pride, too, because Rouverol is the man who built the Votomatic, the voting machine that -- along with its imitators -- left lingering question marks over Florida's 2000 election results. Rouverol said the VoteSure will eliminate the earlier machine's flaws.

As large states such as California and Illinois cast skeptical eyes on touch-screen computer systems made by large and politically connected corporations such as Diebold, Rouverol hopes registrars and voters will end up using his new machine instead. Next year, California will begin requiring that touch-screen machines produce paper receipts. Nevada will require paper receipts this November. Illinois hasn't approved touch-screen -- or "direct recording electronic" -- systems, partly because citizens there have insisted on machines that produce paper receipts.

For a generation, the Votomatic booklets mounted in fold-up plastic booths were practically synonymous with Election Day. Using the machine and its paper ballots, baby boomers installed and removed aldermen, senators and presidents.

The Votomatic was a great and revered contribution to American public life. It saved some registrars thousands of dollars and let others mechanize the voting process for the first time. It replaced 1,000-pound machines that could wipe out a registrar's budget with one invoice. It took power out of the hands of local political bosses who could often persuade vote counters to toss out or overlook opponents' ballots.

But in dozens of elections over four decades, the Votomatic and similar systems were plagued by printing goofs, programming errors and counting malfunctions. Chaos and court battles often followed. And finally, in the 2000 elections, an acrimonious nationwide debate ruined the reputation of Rouverol's creation forever and gave mainstream America the term "hanging chad."

Bill Rouverol refuses to allow that disaster to be his legacy.

William S. Rouverol never intended to develop a passion for voting technology. He briefly studied for the priesthood. He earned degrees in English and engineering at Stanford University. He trekked solo across South America. At the age of 48, he took a two-year sabbatical to study sculpture in Berkeley, where he met his second wife, Sandra, then an undergraduate student.

His work with voting machines comes down to two cases separated by 38 years. Each followed an earnest request from a total stranger. In early 1963 he had been teaching mechanical engineering at the University of California for 12 years and inventing gear systems in his free time. Then a professor of political science named Joseph Harris sought him out for help in building a voting machine.

The lever systems that predated the Votomatic were generally accepted as accurate and difficult to defraud. But at $1,200 and half a ton, the voting booths didn't exactly fly off the shelves. And in counties where registrars were unable or unwilling to shell out such cash, political bosses could often pay or pressure the locals who counted ballots.

Harris' idea was a booklet mounted on a metal or plastic frame. Each page bore ballot questions or candidates' names, and the turn of a page would uncover a new column of punchable squares in the paper card below. The cards were based on an IBM product that companies had used for years to record and process inventory.

But bringing the series of ideas into reality required engineering know-how. That's where Rouverol came in.

Rouverol worked out the angles and measurements of the styluses that voters would hold, the template holes that would guide the stylus, and the mechanisms for holding down the 1/8-inch paper rectangle -- the infamous chad -- after it had been punched out of the card.

Minor punching and counting problems cropped up in test runs, including the 1964 elections in Georgia, California and Oregon. But these hardly dimmed the machine's prospects. Accuracy was never the Votomatic's top selling point; registrars flocked to it for its 20-pound weight and $200 price tag.

State and local elections officials certified the machines, and orders began pouring into Harris Votomatic Inc., the company formed by Harris, Rouverol and other Bay Area investors. They sold the company in 1965 to IBM.

But even as demand grew for the machines, profits were outweighed by bad publicity over counting flaps in Montana, Oregon and particularly Los Angeles.

Rouverol, Harris and a succession of corporate owners continued to tweak the machine, but new problems always seemed to crop up. Card readers jammed, delaying counting for hours or sometimes even days. Confused voters sometimes voted in both parties' primaries. Improperly punched ballots led to disputed results.

Few counties threw out their Votomatic systems. Many more counties kept ordering them, even as still others began in the 1980s to order touch-screen computers or systems that scan ballots for pencil or ink marks. In 1988, the punch-card was the most common type of voting machine, used by about 37 percent of registered voters, according to industry consultants Election Data Services. By 2000, its share had fallen to 28 percent.

Rouverol celebrated his 83rd birthday on an airplane to West Palm Beach, Fla. His partner Harris had long since passed away, and Rouverol had been called to Florida to tell state and federal elections officials why tens of thousands of chads had stayed partially attached to paper ballots.

"I hadn't really been connected to the Votomatic in a couple of decades," Rouverol said. "[But] I decided to go patriotic and help straighten out the elections problem."

Rouverol believes the hanging chad had two causes. The first was the punching mechanism itself. But only voters who don't see a bad punch lose their votes. So the second problem, Rouverol believes, is adequate light.

In a filing cabinet by the wall of his apartment, Rouverol keeps photocopies of several articles from Florida newspapers. A chart prepared by the Miami Herald shows voting errors made on each brand of voting machine used in Palm Beach County. One type of error, the "undervote," was about as common on the Votomatic as on touch screens and bubble-in ballots. Undervoting occurs when a scanner doesn't register a vote for a particular contest because a chad remains attached to the ballot by one or more corners, because it is only pricked or dented, because the scanner makes an error, or because the voter simply chose not to vote. Undervotes on other punch-card machines used there were more than a percentage point higher.

After the Votomatic's patent expired in 1985, other companies moved in with cheaper imitators. Several, including the leading imitator DataPunch, economized by leaving off a lamp that Rouverol and Harris had designed into the Votomatic. Rouverol believes many voters using these machines may have missed their errors more often than Votomatic users.

"I was disappointed that the cheap knock-offs were giving the Votomatic a bad rap," Rouverol said.

Thinking that Votomatic error rates could be improved, too, he designed backlighting for it, called it the Verimatic, and applied for two patents.

But following California's lead, more and more states have banned punch-card machines. The Help America Vote Act, passed by Congress in 2002, promised federal money to counties that replaced them. To Rouverol's chagrin, the legislation doesn't take into account the error rates of specific punch-card systems.

"There was always someone who would've favored one machine over another," said Hilary Shelton, who, as director of the Washington office of the NAACP, weighed in as the act was being formulated. "The last thing anyone wanted to do was get into a discussion of individual manufacturers."

As a result, registrars are taking advantage of the federal subsidies to upgrade technology for counting and other functions, even where mechanical systems have clean histories, such in as Ventura County, Calif.

This fall, fewer than 20 percent of U.S. voters will use punch-card machines, according to Election Data Services.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

After nearly three months of waiting, Rouverol received a package containing the new steel template that he had designed to hold a voter's ballot. He sent the specifications to a Bay Area machinist in November and then waited, calling the machinist periodically to check his progress with the 8-by-4-inch wafer.

Like the plastic template he designed 41 years ago for the original Votomatic, the new one is filled with a grid of 300 small holes. The prototype has two layers, encasing the ballot like a sandwich. And its holes are only a hair's breadth wider than the stylus that plunges through them.

Rouverol is designing the VoteSure -- like the Verimatic -- to screw on to the stands that held the Votomatic up to waist level.

But its key difference with the old machines -- a new shearing mechanism similar in principle to that of a three-hole punch used in classrooms -- should eliminate hanging chads and will allow it to avoid bans on the old machines. California and most other states still allow "shear-card" machines, which, like Rouverol's, have styluses that cut a hole through the ballot, rather than knocking out a pre-scored chad.

One leading shear-card system, DataVote, bears the names of all the candidates and ballot measures, often forcing voters to contend with multiple ballot cards. Only about 6 percent of California's voters used shear-card systems in the March primary. Nearly half of these live in Ventura County, which plans next year to replace its DataVote system with one that scans pencil or ink marks.

In Rouverol's new creation, the 8-by-4-inch steel template rests on two plastic runners so that it covers an 8-by-4-inch opening in the top of the box. The voter inserts the ballot at the top of the template and between its two thin steel plates. A voter will know when the ballot is in all the way because its bottom edge triggers two 13-watt fluorescent bulbs in the box.

Rouverol is redesigning the tip of the stylus, too, enlarging it and giving it an edge that runs around the circumference of the tip.

When the stylus punctures the paper ballot, the edge along the tip whisks past the metal of the template, shearing the paper in a perfect circle. Rouverol plans to apply for at least two patents for the shearing function. He's also trying out "helical" shapes, which would allow the stylus to start two or more cuts on opposite sides of the circle.

The awaited parcel arrived in late February, a couple of weeks before the California primary. Rouverol snapped it into the green box and tried out the punching stroke. Punch after punch, the paper circles fell into the plastic box below. With a depth of 2 and a half inches, the box can collect chads for a longer time, Rouverol reckons, than the term of even the most forgetful registrar in Florida. He hopes to send at least a description of the VoteSure to the country's 3,285 county registrars before the November elections. For a few minutes each day, when he can put aside his distaste for political intrigue and rigged elections, he reworks his calculations and dreams of sending off prototypes of the machine next year.

And he believes he has fertile ground.

Touch screens, which cost from $3,000 to $4,500 each and were used by 29 percent of the nation's voters in this year's primary elections, have several drawbacks and potential dangers, critics say. After a year of news reports, academic studies and conspiracy theories warning of the danger of large-scale voting fraud, several touch-screen systems in Southern California broke down in the March elections, preventing hundreds of people from voting. The next month, California Secretary of State Kevin Shelley followed a state panel's recommendation to ban the Diebold TSx touch-screen electronic voting system used by nearly 2 million voters in San Diego and three other counties.

Shelley required that 10 other counties reapply for permission to use their touch-screen systems. Three have successfully done so, and others may do so soon, but more than 4 million of the state's 15 million registered voters could still be affected. Diebold said it's still in discussions with most of the counties where its machines were decertified.

More importantly, all touch-screen machines purchased after Jan. 1 must produce paper receipts that can be used for a recount. After Jan. 1, 2006, all touch-screen machines must produce such receipts.

Makers of touch-screen machines -- such as North Canton, Ohio-based Diebold, Oakland, Calif.-based Sequoia Voting Systems, and Omaha, Neb.-based Election Systems & Software -- have protested that adding printers to existing systems would be prohibitively expensive and not necessarily helpful. But some counties aren't waiting. Solano County, in the San Francisco Bay Area, abandoned its $4 million contract with Diebold last month and plans to begin using paper ballots that its 170,000 voters will mark with pencil or ink.

Rouverol's best hope for the new VoteSure may lie with the 20 percent of the electorate that never stopped using punch-card machines like the Votomatic. The federal Help America Vote Act, passed in 2002, promises states up to $4,000 for each precinct that replaces punch-card machines with more sophisticated technology. That's about the cost of one touch-screen machine, but most voting precincts require multiple machines, and not all states are willing to cover the difference.

Paper ballots in so-called optical-scan systems can be marked without any special machine. And the computers that scan the marked ballots can be had for less than $7,000. But in Illinois, where 54 counties still use punch cards, the cost gap remains, according to Dianne Felts, the state's director of voting systems and standards.

"We have some counties that are so poor that they won't be able to switch over unless 100 percent of it is covered," Felts told me.

Still, even with their $200 price tags and compatibility with existing Votomatic card readers, Rouverol's machines may face an uphill struggle. Many counties are hesitant to put out any money until new elections standards emerge, and registrars say they may end up ruling out even modified "shear-card" machines such as Rouverol's.

"The problem with the punch card wasn't the chad," said Wendy Noren, who runs elections in Boone County, Mo., and is one of 30 experts advising the federal Elections Assistance Commission created by the 2002 legislation. "The problem was the limited number of positions on the ballot. It was the lack of second-chance voting."

"There's so much uncertainty now," said Los Angeles County registrar of voters Conny McCormack. "I very much doubt that Los Angeles would be looking at a new system before 2008."

Los Angeles County, the nation's largest, is one of at least 32 in California that in November will use optical-scan ballots, which require voters to mark ink dots next to candidates of their choice. McCormack said she'd consider testing a shear-card machine like Rouverol's. But she also said error rates for optical scans and touch-screen machines are close to zero. And the widely feared large-scale voter fraud isn't particularly likely with touch-screen machines, she said.

"Whenever you change voting systems, you get conspiracy theorists," she said. "When you bring paper ballots back from the precincts, what if one of those cars blew up in a crash and all those ballots were lost?"

Rouverol also worries that the multibillion-dollar corporations that sell the new technology may have insurmountable influence with elections officials. The $4,000 they take in for each machine can pay several weeks' salary for a lobbyist or, as Rouverol likes to say, "buy a lot of martinis for politicians."

A more important factor, though, could be resistance to change. Many citizens and elections officials, having once used their new touch screens and bubble-in ballots, are unlikely to go back, said Larry Bird, curator of the Smithsonian's political history collection. Bird is putting together an exhibit -- due to open in July -- called "The Machinery of Democracy," which includes the Votomatic and other voting machines from history.

"The technology that's entrenched is an extremely large barrier to getting in," Bird said. "It's like politics, with the advantage going to the incumbent."

Using punch-card and shear-card machines should seem trustworthy and affordable to registrars and voters, Bird said.

"They've gone from something you can see and hear and feel to something you just touch and go," he said.

Henry Brady, a UC-Berkeley professor who studies voting systems, argues against both punch-card and shear-card systems like Rouverol's because they don't eliminate what's called "overvoting," the error of voting for too many choices on the same race or proposition. An 8-by-4-inch ballot like Rouverol's isn't big enough to print legible script for an election that has more than a handful of races and propositions. Voters can't just look at the ballot afterward and tell who they voted for.

"[But] you've got to admire the man," Brady said. "At 86, he's still working for democracy."

Rouverol lent me a copy of "The Last Lone Inventor," a book about Philo Farnsworth, the San Francisco inventor who conceived much of the technology used in the modern television, only to end up embroiled in a years-long legal dispute with Radio Corporation of America over royalty rights.

"He's not the last lone inventor," Rouverol told me with glinting eyes and a laugh. "I am."

It was the day after the primary, and we were sitting in the living room of Rouverol's Berkeley apartment. I had come to return the Farnsworth book. The lunch hour was approaching and voices were starting to rise from the row of upscale cafes and restaurants along the avenue below.

Rouverol's back was to the window and his blue eyes were wide behind glasses that caught the glare of the early-afternoon sun. On the first warm day in March, he was wearing his brown slacks and a long-sleeved patterned shirt left unbuttoned at the top. The table was piled high with photocopied news accounts of the last, greatest chad disaster, patent literature, and graph paper covered with Rouverol's intricate schematic drawings.

Rouverol had arranged for the machinist to come by at 10 a.m. to discuss flaws in the steel template. I waited with him for an hour before the man called to say he wouldn't be able to make it by that day.

Around noon, the last lone inventor took the elevator down from the second floor and shuffled out the door to check his mailbox. Rouverol goes gingerly; though his fingers retain the energy and dexterity of a much younger man, a degenerative nerve disorder has robbed him of much of the feeling in his feet.

Rouverol's time and attention had always been taxed by his career, but particularly by patent disputes. He has spent most of his work life developing low-noise gear systems, and even now has three gear patents pending. In a refrain common among individual inventors, he told me of corporations' deep pockets, their armies of lawyers, and their ability to drag out patent suits for years after they steal technology. He had been bruised himself, he said, in dealings with Ford and Harley-Davidson.

More recently a dispute with business partners at his Axicon Gear Co. led to personal problems. Axicon had licensed his technology to make parts for the Segway, a gravity-driven scooter that was widely heralded but proved a commercial flop. After limited partners pressed him to renegotiate royalty payments, the self-styled Last Lone Inventor resigned as general partner. The dispute with the partners, several of whom are prominent local business owners, was the next-to-last straw for Sandra Rouverol.

"The business side of inventing can be pretty sordid," he said. "She felt hated by everyone in town who had invested in this Axicon Gear Company."

"All those years of turmoil and confrontation -- she kind of stood by me through all the stuff I had to deal with. The divorce is pretty much a byproduct of the two new patents. When it began to loom that there would be two new companies, the new Axicon and the VoteSure, she went to see her attorney.

"Everybody in the family has no good word for me because I've gone ahead with doing what I had to do, which is inventing."

In July 2002, after 36 years of marriage, Sandra Rouverol, 56, filed for divorce and moved to Washington state. Soon after, Bill Rouverol moved out of their three-story house with the bay view. It now stands empty, a eucalyptus tree towering alongside.

After his wife's departure, Rouverol began dating again. One of his love interests is a librarian in her 50s.

But more importantly, he said, he has a lot more time to work on his new inventions.

"That's what I'm here to do: invent," he said. "I think it keeps me alive."

Shares