Why is it that now, when most trailers manage to give away the entire plot of a movie, the movies themselves feel like no more than extended trailers? World War II from Pearl Harbor to VJ Day arrives about an hour into Nick Cassavetes' "The Notebook," and it takes up no more than five minutes of screen time -- and that's pushing it. That in itself isn't a flaw -- the plot doesn't focus on WW II.

What's strange is that what the movie does focus on -- a 1940 summertime romance that turns into the love of the summer lovers' lives -- feels less like a developed story than a succession of montages. Here are Noah (Ryan Gosling) and Allie (Rachel McAdams) laughing over an ice-cream cone. Here they are laughing on the beach. Here they are laughing as they use a rope to swing Tarzan-style into the old swimmin' hole. And -- presumably after they tire of all this activity -- here they are just laughing.

"The Notebook" opens with a plaintive note being plunked on a lonely piano while a single sculler rows against a crimson evening sky and seagulls attend overhead. In other words, from the first shot this movie tells you you're in for it.

Taken from the novel by Nicholas Sparks (adapted by Jeremy Leven and Jan Sardi) and set in North Carolina, "The Notebook" is the old one about the poor, honest boy who falls for one of "the summer people," a good-hearted rich girl whose parents expect her to make a better match. Circumstances intervene to pull them apart. Her parents drop a bomb on their burgeoning love. The "Japs" drop lots of bombs on Pearl Harbor. Allie sets off for Sarah Lawrence, Noah sets off for Patton's Third Army. She meets a boy (James Marsden) her parents can approve of. He returns to his small town to realize his dream of restoring its abandoned plantation house. This is all narrated by James Garner as a nursing-home resident reading Noah and Allie's tale to another resident -- played by Cassavetes' mother, Gena Rowlands -- a woman suffering from the onset of senility. And if you can't figure out their function in the plot before it's explained, you may be suffering from senility yourself.

"The Notebook" positively wallows in '40s nostalgia, particularly for small towns. You know just how country-cute Noah's hometown is when he comes home from the war walking down a dirt road and his father (Sam Shepard) sees him because he just happens to be out on the porch, settin' a spell. (Somebody should tell Sparks that most small towns had acquired at least a few telephones and a telegraph office by 1945.) How small is the town? It's so small that Noah and Allie can top off a date by lying down in the middle of Main Street to gaze at the traffic lights. (The town car must be over in Mayberry for the night.)

Nick Cassavetes may want to believe he's working in a classic Hollywood style. But I think if any of the old moguls were alive to see "The Notebook" even they would blanch at what Cassavetes tries to get away with here. The movie not only approaches a level of shamelessness you have to see to disbelieve, it does it in a manner that's both inept and crass. This homespun junk may have been grotesque when the studios were turning it out in the '40s, but I think the moguls and the filmmakers who worked for them -- the hacks as well as the talents -- sincerely wanted to make good movies that would involve the audience.

It's not that Cassavetes wants to make a bad movie. It's that I don't think he believes in any of it even on the level of proficient weeper. He seems to think that if he just plugs in the signifiers -- the Coke signs and great-looking cars, the movie marquees and standards on the soundtrack (though Billie Holiday seems a tad hip for a '40s small town -- Alice Faye would be closer to the mark) -- they'll be enough to whisk us back to "a more innocent time."

That it's bearable at all is because in the first hour there's some genuine chemistry between Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams. Cassavetes allows her to be seen with her mouth open in laughter far too many times, which is a pity because her full-bodied giggle is what tells us right away that Allie is no stuck-up rich girl. "That child's got too much spirit for a girl of her circumstance," says her mother (played by Joan Allen, who delivers a performance she ought to be ashamed of). Terrible (and typical) a line as that is, it suits Allie. McAdams has a manic streak she didn't get to show in her last role as the cool queen bee in "Mean Girls." She's got a broad grin that peels her lips back over her pearly whites and a spark in her eyes. Cassavetes nearly ruins her best moment, the talking jag she goes on just as Noah and she try to make love for the first time. Cassavetes directs the scene to be gushy when the real romance (and the humor) is in Allie's nervousness. It's McAdams' last really good moment because right after it she's called on to do little more than cry or emit slightly hysterical laughter in scene after scene. (Though her reaction after she has her first orgasm is a small triumph.)

Before Ryan Gosling is inexplicably put into the long hair and beard of a '60s college student in the second half of the movie (though it's 1947), he does some impressive work. I admit to not having seen in Ryan Gosling what some of my colleagues have. Maybe the reason he's so good here (again, as with McAdams, in the first hour before the arc of the story and Cassavetes' direction let him down) is that he knows how to hold himself in reserve from the hokey plot mechanics -- without holding himself in reserve from McAdams. Gosling has a nice sly sense of underplaying. He has a particularly good moment where he overhears Allie's parents tearing him down and smiles to himself. You find yourself looking at Gosling wondering what that smile means -- his knowledge that their tirade won't affect their daughter's love for him? Whatever it means, it's the key to the charm he has here, like the shy smile that James Dean showed in some moments of "East of Eden." In some ways this is a private performance -- but that privacy draws you in and the charisma Gosling shows in the movie's first hour is the real deal.

Nothing else in the movie is. David Thornton, as Allie's father, has been given a curly black mustache that, were it accompanied by a chef's hat, would qualify his picture to be on a cardboard box proclaiming, "Your fresh hot pizza is ready!" James Garner's performance would just be a glide through the movie if, in one of the big heart-tugging moments, he weren't treated horribly by Cassavetes. The pleasure of watching James Garner has always been his casual, offhand affect. But when he has to break down in tears here, it's a violation of Garner's dignity. Not because it's undignified for a man to cry. But because it's objectionable to watch a good actor made to emote over pap. Cassavetes violates Garner's screen persona in this scene for the sake of wringing tears from the audience.

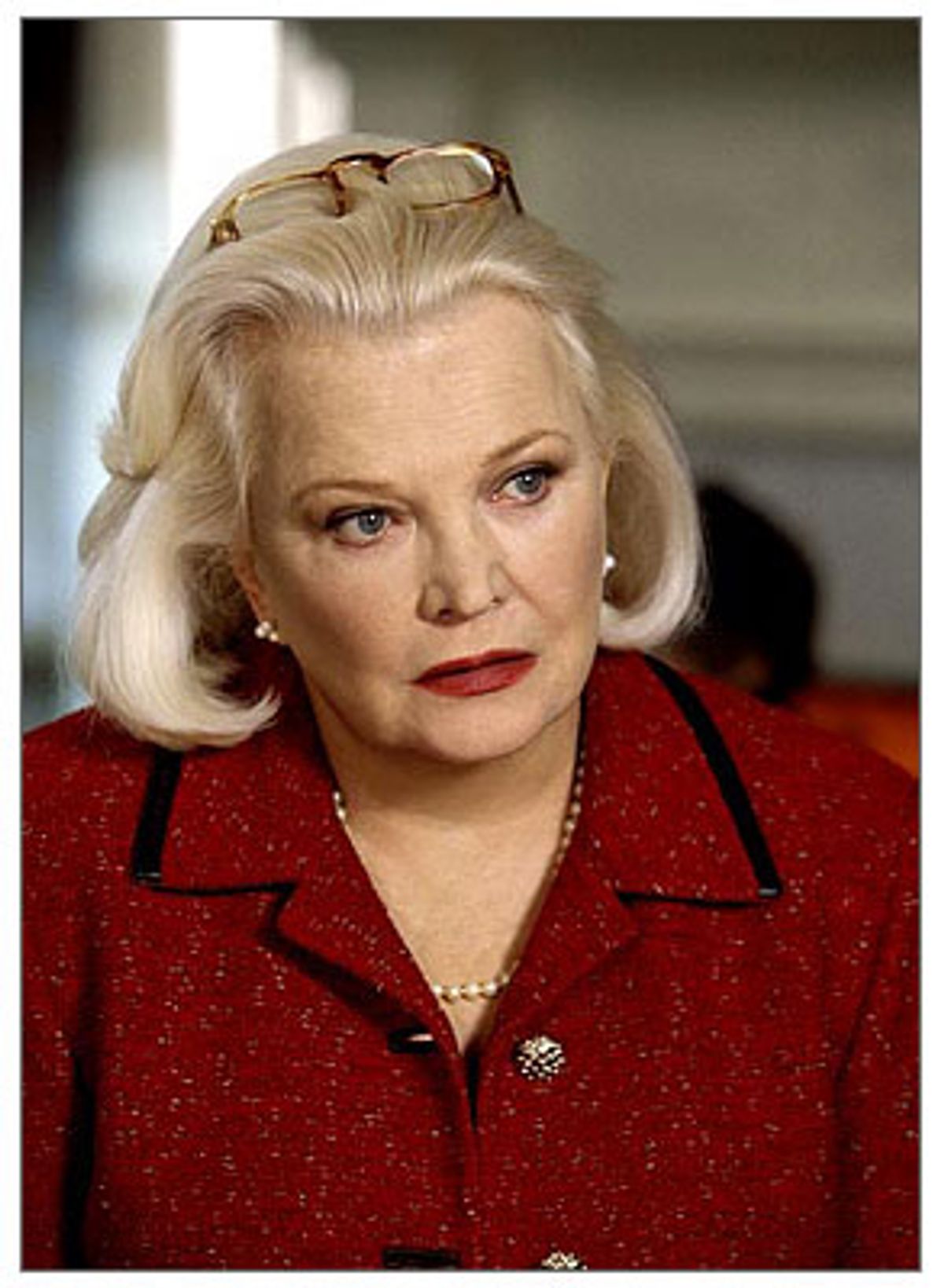

Maybe Cassavetes knows better than to pull that crap with his own mother but he's not above using her to make us mist over, even though nothing about Gena Rowlands suggests the fragility of a woman losing her memory. Rowlands tries, and there is something touching in the delicacy with which she takes Garner's arm. But she looks like she could shrug off her paisley shawl and cut through the surrounding crap with her New York bark. "The Notebook" may be about a heroine who has to defy her controlling mother in order to live her own life. But it made me wish Rowlands was enough of a controlling mother to tell her kid what a load of horse pucky he'd dropped on the screen.

Shares