Bombing birds' nests is actually a boon for bird-watchers, since the ones that survive become rarer, and more exciting to spot. There's no one more qualified to keep our nation's forests healthy than a former timber lobbyist. The best person to uphold the Endangered Species Act is the lawyer who once argued before the Supreme Court that the act should be gutted. And pollution from power plants that cuts short the lives of 30,000 Americans a year is nothing to get upset about as long as you pledge your commitment to the best science in the name of "Clear Skies."

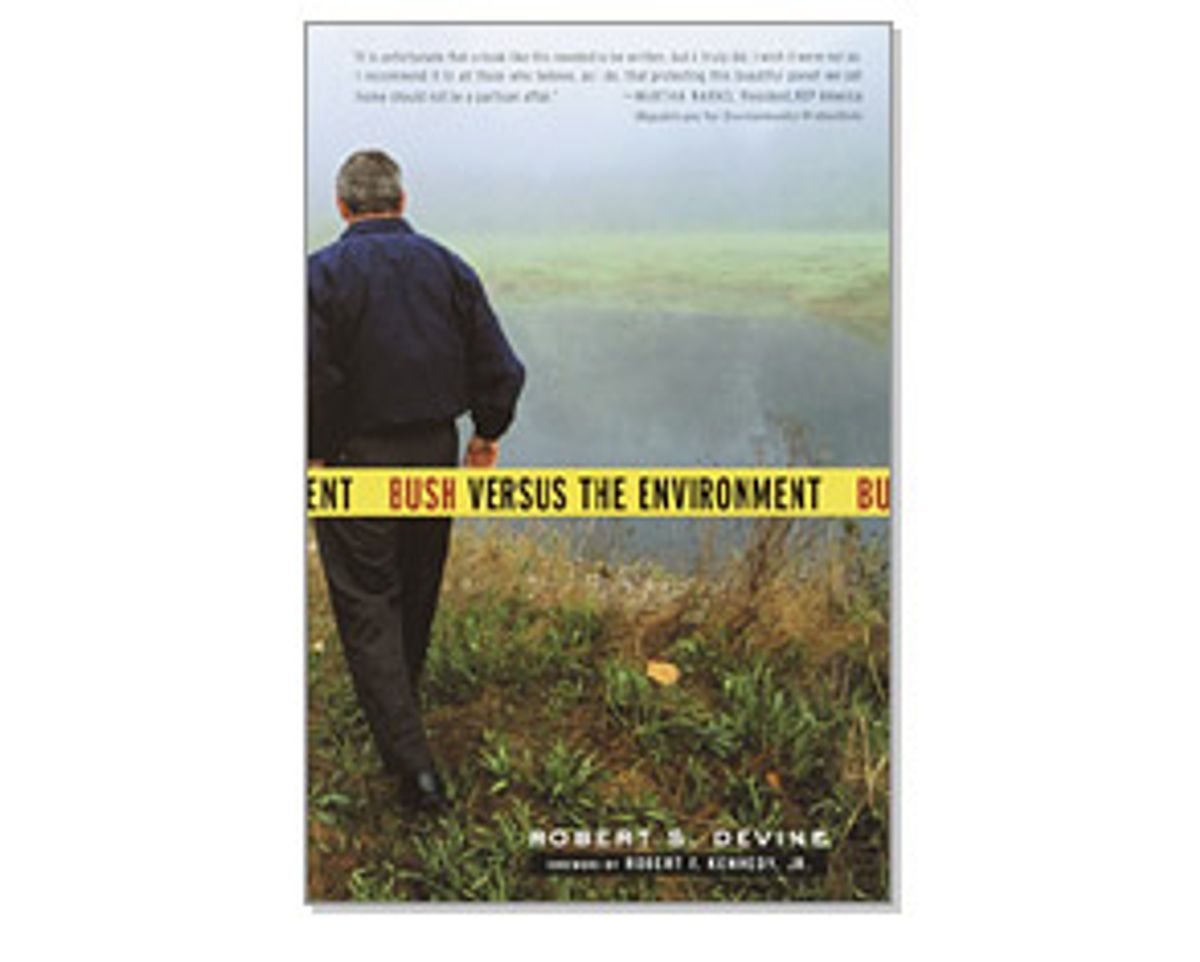

In his new book, "Bush Versus the Environment," Oregon journalist Robert S. Devine documents a record of environmental neglect and enmity that's so grim as to be laughable. He uncovers how in the name of "new environmentalism" the Bush crew pursues an agenda that's so radically pro-industry that even conservative Republicans are reluctant to cop to it publicly, cloaking their new policies in Orwellian happy-speak.

More than a laundry list of green crimes, "Bush Versus the Environment" is an analysis of how these anti-regulation administrators undermine laws they don't agree with, even if they're sworn to uphold them. Through a combination of benign neglect -- such as underfunding existing programs and settling lawsuits with corporations on absurdly favorable terms -- Devine shows that the Bush administration is doing far more to affect the stewardship of our public lands, air and water than even its most explicitly articulated policies suggest.

Devine has covered the environment, natural history and the outdoors for more than 20 years for publications such as the Atlantic Monthly, Audubon, National Geographic Traveler, and Travel & Leisure. Salon spoke with Devine by phone from his home in Corvallis, Ore.

How would you characterize the Bush administration's overall environmental philosophy?

I would break it into two pieces. One is simply old-fashioned industry greed. Some of the extractive industries, like fossil fuels, and a lot of industries that pollute are pretty heavily represented in governmental appointees all the way to the top, especially with the vice president. These industries are looking out for their bottom lines in a very classic, old-fashioned, all-too-familiar way.

And the other strain is what they would call "new environmentalism." I'm sure you've heard the phrase from [Department of Interior] Secretary Norton.

How would you define it?

Using the market [to effect environmental protection]. First of all, it's not new. It's certainly been done before, and there are some things that have worked out, especially on a smaller scale. When you see, for example, people at a local level getting together -- ranchers, farmers, environmentalists, local merchants, citizens and the local people from the federal and state government -- to talk about how to, say, restore salmon in a watershed in a way that works out for local business and the local people living off the land. Some of those programs have worked out very well.

But it seems to falter most often when it gets to the national and international level, where multinational corporations are involved. I don't think that they typically have the same sense of collaboration as local people do. Now, the Bush administration people would argue otherwise. They would point to the acid rain program probably -- that's their favorite example.

What's the acid rain program?

The basic idea is trading pollution credits so you can cheaply reduce emissions at one plant, and not reduce pollution and perhaps even increase it at another plant, but overall across the country reduce emissions. This was instituted 14 years ago now, and has indeed created some significant reductions -- various studies show somewhere between 35 and 40 percent. That is the example that they show as the shining exemplar of how well market-based programs and trading programs can work.

On the other hand, I looked at Germany where they had a similar acid rain problem in the Black Forest. They saw this as a problem that needed to be dealt with swiftly and thoroughly. They instituted a straight-ahead mandatory reduction program, and instead of taking 14 years to knock it back 35 or 40 percent, in five or six years they knocked it back 90 percent, and apparently, at no great cost to industry. It wasn't prohibitive.

So, you have to wonder if market-based programs sometimes aren't simply smokescreens for business as usual.

It seems like one of the administration's strategies is to appoint anti-regulatory officials who used to work for the industries that they are supposed to regulate.

Out of the dozens of appointees I looked at, I did not see one single person who was appointed by Bush who had any kind of environmental credentials or background. In fact, I can't even think of one who was sort of neutral. Every single one I looked at had a strong pro-industry background -- the extractive industries, the polluting industries, mining and coal, automobile and logging and so forth.

Mark Rey is a good example -- 18 or 20 years as a timber lobbyist for the major trade groups for the timber industry, fighting all sorts of environmental protections. His career has been basically trying to remove obstacles to logging, and by "obstacles" what often is meant is citizen input, appeals, any kind of regulation that impedes timber. Then there's James Connaughton, the Council on Environmental Quality chair, who is, in a strict sense, the closest environmental advisor to the president. His background is as a lawyer representing General Electric with respect to their Superfund sites. That was his specialty: trying to avoid Superfund problems for big corporations.

Gale Norton came to Washington, D.C., with James Watt in the '80s. She has devoted her life to deregulation. She made an argument before the Supreme Court, in an attempt to undermine the Endangered Species Act, that you should only consider direct "taking" -- like shooting -- to be a threat to endangered species, rather than things like habitat loss. That would completely gut the Endangered Species Act. And now she's the one enforcing it. Since she came on as interior secretary the Bush administration hasn't listed a single species under the Endangered Species Act, except when ordered to by a court, or if it was already in the works from the Clinton administration.

What about Bush's judicial nominees?

That's something that gets overlooked a lot. In judicial nominations people tend to talk about litmus tests like abortion -- pro or anti. I think that if you wanted to actually look at one litmus test that might hold true, even more generally, it would be that they're anti-regulatory. One example -- it's extreme but it's kind of interesting and funny -- is William Haynes II, general counsel for the Defense Department, who has been nominated for a federal appeals court position.

He was involved with what now is kind of a notoriously tragicomic case in which some conservation groups asserted that military bombing test runs on some Pacific islands were breaking the migratory bird treaty, because the islands were nesting places for migratory birds. The defense argued that environmentalists should actually be happy with the bombing of the bird islands, because it would make the birds more scarce -- less common -- and that bird-watchers preferred seeing uncommon birds.

Haynes now claims that he didn't know about this particular defense, that his team did it without his knowledge.

You write about a tactic the Bush administration uses called "sue and settle," in which they settle lawsuits brought against the government by companies in terms that are very favorable to the companies. Can you give some examples?

It's a backdoor way of creating policy on the sly, and shifting the blame, if there is blame, to the companies ... It's a settlement that the government shouldn't make if it was really defending the environment, because there's a strong case to be made.

There was a case that Utah brought that was sitting dormant for many years since the mid-'90s. It was about the way that the Bureau of Land Management was designating wilderness, or pre-wilderness, protecting areas that appeared to have wilderness qualities, and how they had gone about identifying those areas. While Clinton was president, Utah didn't do anything, so you have to think it's because they didn't think that they were going to get anywhere.

Then when Bush came in, a couple of years into his administration there was suddenly a settlement announcement that came out of nowhere. It blindsided everybody. In fact they gave Utah more than Utah was asking for in the suit. The upshot was that potentially tens of millions of acres of Bureau of Land Management land are being opened to development, especially oil and gas exploration and drilling. That was considered very much a sweetheart deal.

Another case of a weak defense was the roadless rule, which was an attempt to set aside some 58 million acres of National Forest roadless areas as wilderness, and keep it from being developed. This was a case where the government was sued by Boise Cascade, the state of Idaho and some other plantiffs to strike down the roadless rule. And they just didn't defend it. They didn't appeal it. They gave it a weak defense and lost. They had a very strong case according to all the conservationists looking at this, but they just chose not to appeal. So, the conservationists were allowed by a judge to step in and replace them, and they took it to their appeals court, and they won the case, which does indeed show it was a strong case.

Do you feel that the Bush team misrepresented themselves in the 2000 campaign? Or did we get what we signed up for?

I do think that Bush misrepresented himself. Let me read a quote to you: "Our duty is to use the land well, and sometimes not to use it at all. This is our responsibility as citizens, but more than that. It is our calling as stewards of the earth." I think that's very much a misrespresentation of where their policies have actually gone.

When he was campaigning, he focused on other issues mostly, but he talked about the environment some, and he never said: "Look, folks, we just think that these extractive industries and polluting industries are far more important than most environmental protections, and we're going to deregulate almost everything." He never said anything remotely like that. And it may sound almost laughable, but James Watt said things like that. He was right out in the open. I have a quote from him: "We will mine more, drill more, cut more timber." And he also talked about things like there probably wasn't really a need to save things for seven generations, because the Apocalypse was coming along anyway. He said that stuff in public. It was very different. And he failed utterly, and got driven out of office.

I think the Bush administration and other hardcore Republicans learned from that. The environment is popular, it's not a partisan issue. Most Republicans, large majorities of them, still support these environmental protections.

Do you think, given Iraq and terrorism and the economy, that the environment will be a big issue in the 2004 election? Will people get galvanized around it?

Well, some people certainly will. Whether it's a significant number, whether it happens among the key people in the key states, it's hard to say, but it looks as if it might be a significant factor. It will certainly not rise to the level of Iraq and terrorism and the economy. But it's a pretty high-level secondary issue. Even if it's one of only three or four factors somebody looks at to make a decision, that's still very important. And they know it's important. Recently EPA administrator Mike Leavitt has been running around the country doing a lot of environmental fence mending and public relations. The park service directors have been visiting a lot of parks, and trying to downplay the whole flap over the park funding. They're concerned about their environmental image.

Shares