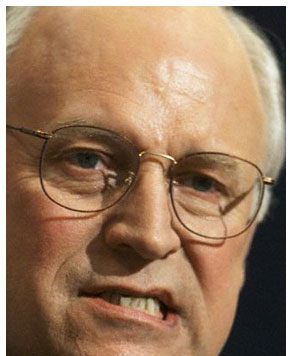

In Washington, political identities cultivated over decades can crumble in a minute. Vice President Cheney presides under the Constitution as president of the Senate and is addressed as “Mr. President,” but former Rep. Cheney is not a man of the Senate, which considers itself to be as distant from the House of Representatives as the Metropolitan Club is from the Bullfeathers saloon near the House side of Capitol Hill. Cheney’s executive branch credentials were as President Ford’s wunderkind chief of staff and the elder Bush’s secretary of defense, but on the Hill he is remembered as the former House Republican whip during the Reagan administration, his only previous elected position.

In the House, the Republicans were then in the minority, and Cheney was the driver behind the scenes of the hard right, protector of obstreperous young reactionaries like Newt Gingrich, yet still presentable to the broader establishment as a respectable saturnine figure. Those who observed him operate in the House saw through his veneer, but he elevated himself by advancing the persona of the statesman.

The self-control that had served him so long broke down in public on June 22 on the floor of the Senate during a photo session. As Cheney was posing with members, Sen. Patrick Leahy ambled over. Leahy, the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, had recently been critical, along with other Democrats, of no-bid contracts in Iraq granted to Halliburton, the company Cheney had run and in which he still holds stock options and receives deferred compensation (despite his prior claims to the contrary). “Go fuck yourself,” greeted the vice president.

At first, Cheney’s spokesman appeared to deny that those words had been spoken: “That doesn’t sound like language the vice president would use.” But Cheney raced onto Fox News to hail himself as courageous for emotional authenticity. “I expressed myself rather forcefully, felt better after I had done it.” Then he elaborated that his ejaculation was an administration policy: “I think that a lot of my colleagues felt that what I had said badly needed to be said, that it was long overdue.” Leahy’s seeming civility, he explained, was just a charade: “I didn’t like the fact that … he wanted to act like, you know, everything’s peaches and cream.”

A main source of Cheney’s effectiveness and image of competence has been his ability to avoid putting his cards on the table. But in a moment of pique, he dropped the entire deck. His game face fell and his malicious streak broke through his mask. Cheney’s blandness had suggested he was deliberate, experienced and imperturbable. In the first Bush administration, victory in the Gulf War solidified that reputation. When the president was defeated, Cheney was not. He emerged from those ashes unscathed.

Just as the elder Bush picked someone who might have been one of his sons as his vice president, younger Bush chose a version of his father. Dan Quayle was light as a feather, another scion from a wealthy Republican family, an ingenue in policy, the vice president as understudy. Cheney was to be the mentor of the Bush family’s would-be Prince Hal and was widely believed to represent the old man’s dampened realism. In 2000, he was put in charge of selecting George W. Bush’s running mate; he collected the private dossiers of potential candidates and chose himself. Asked who had vetted Cheney’s financial records, Karen Hughes, Bush’s communications aide, replied, “Just as with other candidates, Secretary Cheney is the one who handled that.”

Bush’s executive branch has been concentrated in Cheney. He has been as powerful as Quayle was irrelevant. It was Cheney who said to United Nations weapons inspector Hans Blix as he embarked on his mission to Iraq, “We will not hesitate to discredit you”; Cheney who personally tried to force the CIA to give credence to Ahmed Chalabi’s fabricated and false evidence on WMD; Cheney who, along with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (to whom he was deputy in the Nixon White House), undermined Secretary of State Colin Powell at every turn; and Cheney who is the neoconservatives’ godfather. (Cheney’s link to the neoconservatives largely developed after the last Bush administration and was arranged by his wife, Lynne Cheney, cultural warrior on the right, former chairwoman of the National Endowment for the Humanities and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, the principal neocon think tank.)

Even before his outburst in the Senate, Cheney had come to stand for special interests, secrecy and political coercion. Under the stress of Bush’s falling polls, Cheney cracked.

Bush still strains to project optimism and cast the Democrats as demagogic pessimists. His campaign this week produced a commercial, “John Kerry’s Coalition of the Wild-Eyed,” that featured snippets of Al Gore, Howard Dean, Michael Moore and Kerry criticizing Bush. Interspersed among the Democrats was a frothing and saluting Adolf Hitler. Bush’s apparent remake of the “Springtime for Hitler” number from Mel Brooks’ “The Producers” is partly an attempt to counter the box office success of Michael Moore’s “Fahrenheit 9/11.” Running against Hitler is also an effort to transform the sober Kerry, instead of Cheney, into the “wild-eyed” threat.

Perhaps the grandest political gesture Bush could make would be dropping Cheney. When Cheney bursts through his mask he reveals not only his own face but Bush’s. However, Bush has no option. “The idea of dumping Cheney is nuts, makes no sense,” one of Cheney’s political advisors told me. “One of the reasons he’s there is they don’t have someone to anoint as a successor.” After all, where would it leave Jeb Bush in 2008? “Dumping Cheney would be seen as a sign of weakness. Cheney is very popular in the party.” The Bush campaign’s premise depends on turning out the maximum Republican vote. Bush can no more repudiate Cheney than he can repudiate himself. Cheney will never hear from Bush the words he hurled at Leahy.