Throughout the '80s and '90s, in the days before Sept. 11, many people already believed America was at war. These were the Culture Wars, and fighting on the front lines were tenured humanities professors from America's elite universities, proponents of what has come to be known simply as Theory. Armed with the insights of postmodern philosophy, they shocked and awed through their intellectual acrobatics, decentering the subject, doubting the existence of Truth and destabilizing metanarratives. Their aim was not to literally destroy Western Civilization (as some of their ideological and philosophical opponents suggested) but to deconstruct it.

Those were heady days for academics, when the mere mention of the word "poststructuralist" made folks shake if not with fear then at least with outrage.

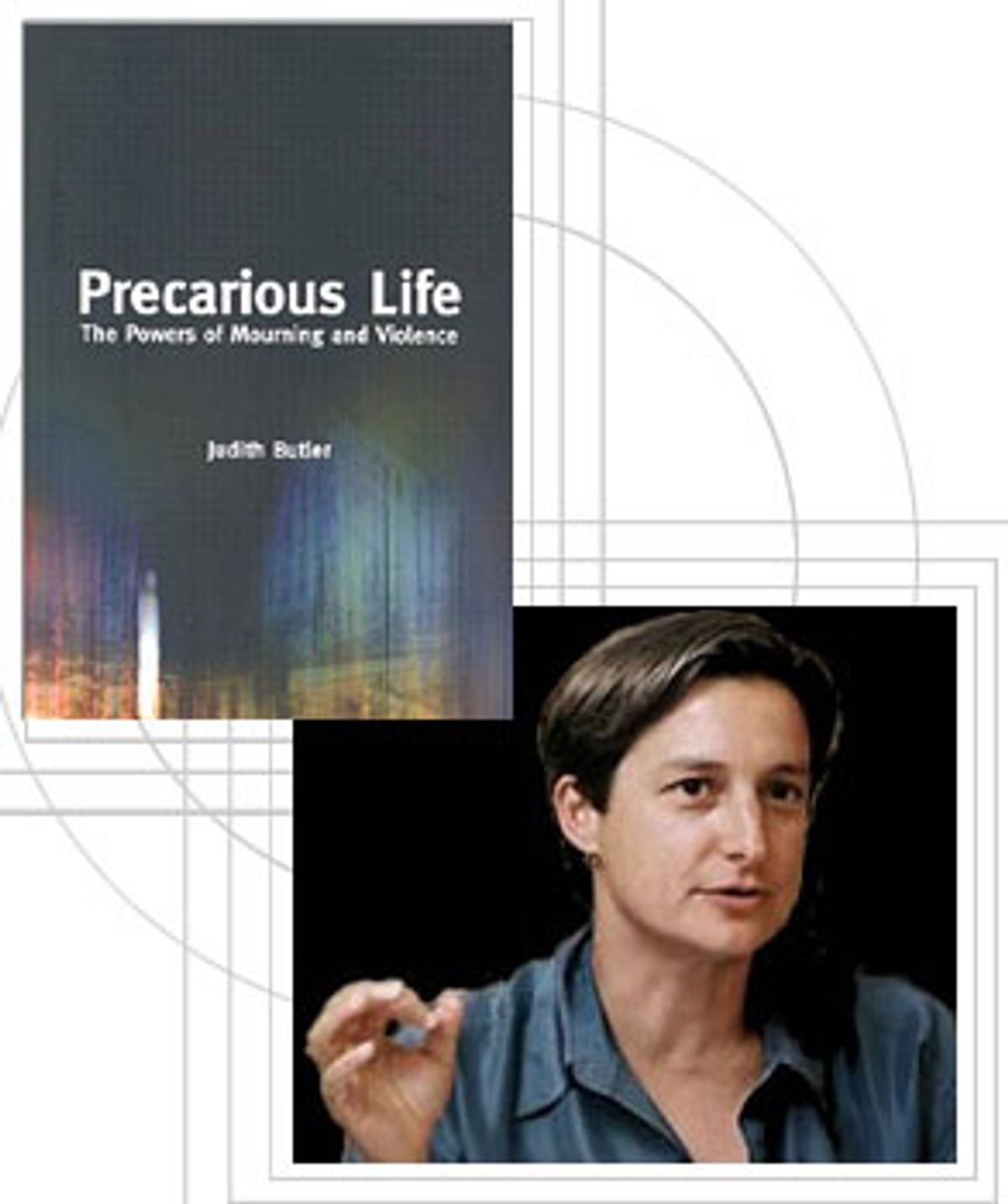

At the center of the raging debate about the culture wars stood the feminist philosopher Judith Butler, Maxine Elliot professor in rhetoric and comparative literature at the University of California at Berkeley. She is the author of the now classic "Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity," one of the defining works of queer theory. With over 100,000 copies sold, it is academia's equivalent of a platinum album. Over the last decade Butler has published a steady stream of theoretical work, most of which revisits and reformulates the fundamental ideas explored in "Gender Trouble": the social construction and performative nature of sex and gender. Her latest offering, however, "Precarious Life: The Power of Mourning and Violence," relates to her seminal work only tangentially, if at all. It is a collection of five provocative political essays that reflect on our post-9/11 world.

Back in the late '90s, Butler appeared as the embodiment of postmodern thought to both conservative and liberal critics alike. The immense success of "Gender Trouble" and the appeal of her analysis among college students (there was even a fanzine, Judy!, printed in her honor) made her a favorite target in the media and among fellow academics, who may or may not have envied her popularity. Articles dissecting Butler's postmodern prose abounded, an especially notable one being Martha Nussbaum's blistering critique in the Atlantic Monthly. (Butler was once referred to by Camille Paglia, in her Salon column, as a "slick, super-careerist Foucault flunky.") Butler even made headlines in the New York Times when she won an award for "Bad Writing" -- writing that was too theoretically obtuse, a trademark of postmodern critique. She, in turn, published a clearly written defense of her style on the Times' Op-Ed page, making the case that complicated language is sometimes required to convey nuanced ideas.

Today, however, theory no longer frightens and fascinates with the same force. We now inhabit a world in which there are more pressing things to be concerned with and to be afraid of, one in which foreign affairs take precedence over matters of philosophy. Recent historic events -- Sept. 11, the war in Iraq and even the evolving protest movement for global justice -- have challenged (excuse me while I use a properly obtuse term) the hegemony of postmodernism in the academy. As a result it is fashionable not to flaunt poststructural proclivities but rather to claim that we have, in fact, actually reached the End of Theory.

This end was declared immediately after the attack on the World Trade Center, in the pages of the Chicago Tribune. A good number of people, rightly or wrongly, had come to equate postmodernism with moral relativism, as well as with a rejection of notions like truth and even the existence of an objective reality. When faced with the very real horror of Sept. 11, such a position seemed not only spurious but actually, to some, downright insulting. For many it was the end, and good riddance.

Articles published in both the New York Times and the Boston Globe corroborated this, implying that erstwhile postmodernists were distancing themselves from the very sort of thinking that had garnered them notoriety. The two newspapers reported on a high-profile humanities conference that took place in 2003 in Chicago during which some previously unrepentant theorists publicly expressed doubts about the effectiveness of postmodern critique. An essay reprinted in a recent issue of Harper's posed the question: "Has critique run out of steam?" Finally, the publication of a new book called "After Theory" by the English Marxist scholar Terry Eagleton, who is most notable for having written "Literary Theory," the definitive introduction to postmodern and poststructuralist thinking, has inspired similar articles, including a lengthy feature in the Christian Science Monitor earlier this year and a more recent story in the New York Times.

At first glance it is easy to mistake Judith Butler's latest offering as evidence of this trend of theorists distancing themselves from their former, more postmodern selves. But that would be to misread "Precarious Life" entirely. Without a doubt, the collection marks an interesting departure for the author; it is her most straightforward and political book to date. The volume addresses a range of very real and pressing contemporary concerns: Our government's response to Sept. 11, the charge of anti-Semitism, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Guantánamo detainees. At one time her sexuality and status as a postmodern queer theorist might have potentially marginalized her, and today it seems that Butler's politics could pose the same threat.

With the end of theory allegedly upon us, precious few have come forward to defend the postmodern position. Butler does not explicitly do that in "Precarious Life," but the volume provides an eloquent and convincing defense of critical thinking in general. The essays, more Susan Sontag than Jacques Derrida, examine the reality of our current political situation. The prose is laced with a passion that is unbefitting of works of philosophy, and Butler generally steers clear of theoretical jargon in favor of clearer and more precise language (at least in comparison to her other work).

These essays, however, are certainly not bereft of theory; this is still Judith Butler writing. In one chapter, she considers Michel Foucault's concept of "governmentality," relating it to the indefinite detention of prisoners at Guantánamo Bay. In another she explores the implications of Emmanuel Levinas' notion of the "face," something that communicates what is human and expresses the fragility that unites all of us, in hopes of outlining an ethics of nonviolence.

The first essay, "Explanation and Exoneration, or What We Can Hear," calls attention to the rise of censorship and the anti-intellectual atmosphere that followed in the aftermath of Sept. 11. Butler examines the way intellectual positions considered "relativistic" or "post-" have been condemned as "complicitous with terrorism" or at least as a weak link in the struggle against it. The world has become one in which only two positions are possible: "Either you're with us or you're with the terrorists." Those who sought to understand the events leading up to the attacks were (and, in some quarters, continue to be) censured as "Excuseniks," as somehow exonerating those who committed violence by trying to understand what factors -- political, economic, social or otherwise -- might have led them to do so.

Butler insists that in times like these, critical engagement is more vital than ever. "I argue that it is not a vagary of moral relativism to try to understand what might have led to the attacks on the United States," she states in the introduction. In fact, for Butler it is quite the opposite. A quest for understanding does not stem from a lack of ethics, an absence of moral outrage, or an insensitivity to the violent atrocity. Instead it is rooted in a response to the grief one feels at the loss of life and the suffering inflicted on our fellow humans.

Which brings us to two of the fundamental themes of "Precarious Life": grief and mourning, the common and yet mysterious responses we all feel in the face of tragedy and death. Butler, like many critics on the left, perceives 9/11 as a missed opportunity, an opportunity to recognize our own vulnerability and fundamental connectedness and to construct a politics accordingly. We have been offered "a chance to start to imagine a world in which violence might be minimized, in which an inevitable interdependency becomes acknowledged as the basis for global political community." It is one that has been passed up, at least thus far.

Butler's second essay, "Violence, Mourning, Politics," is a psychoanalytic investigation of why the opportunity was not taken. She applies concepts of mourning and melancholia to the national mood in the wake of 9/11. Melancholia is disavowed mourning, or, as Butler puts it, a "derealization" of loss. Butler points out that on Sept. 21, 2001, just 10 days after the attacks, President Bush declared that the time had come for grief to be replace by resolute action. What is it about grief, she wonders, that Bush, and in fact all of us, are so afraid of? We can rush to banish our fears through resolute action, which in this case was to wage war, and thus propagate further violence. Yet, no amount of aggression can "will away this fundamental vulnerability." Butler's point is that to create a world that is less violent, "it is no doubt important to ask what, politically, might be made of grief besides a cry for war."

The aggressive response to the grief felt after Sept. 11 led to more loss of life. But Butler's point is to highlight how some lives, precisely those that came to an end through our resolute action, are regarded as unworthy of grieving. There is a "hierarchy of grief," and Butler is concerned about the countless numbers of people, war casualties and victims of occupation, for whom there are no names uttered, no narratives recounted and no obituaries written. These lives are, in effect, dehumanized.

The essays that make up "Precarious Life" seem to be underscored by a single question, one that motivates and connects them: Who counts as human? This is the problem that concerns her in her consideration of grief and mourning, her essay on the lives of Palestinians in the occupied territories and the Guantánamo piece, "Indefinite Detention." What Butler is analyzing are the ways in which some individuals are not protected by law. Unnamed and unmourned, they are not counted as fully human.

Here readers can forge some links between Butler's latest work and "Gender Trouble." Both books testify to the author's nerve. Each is concerned with the horizon of the human. No doubt this was Butler's focus when she wrote "Gender Trouble," when, as she puts it when I speak to her by telephone, she "felt that certain ways of living and loving were not being recognized or valued."

The "unlivable lives" and "ungrievable deaths" that seem to have affected Butler most recently are those of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. In a sense, Butler is "coming out" again with the publication of these essays: this time not as queer, but as a post-Zionist Jew directly opposing American policy, specifically on the subject of Israel. "I like this idea, the phrase 'post-Zionist,' because I was brought up Zionist, and I want my current identification to reflect this journey," she says.

Butler's commitment to standing up for Palestinian lives was cemented during a trip to the occupied territories in January of this year. The trip, she told me, made her physically ill. The sickness continued to plague her as she wrote the fourth essay in "Precarious Life," "The Charge of Anti-Semitism: Jews, Israel and the Risks of Public Critique," originally published in the London Review of Books. The essay is a response to Harvard University president Lawrence Summer's remarks in September of 2002 that conflated criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism. Butler dissects the ways that charges of anti-Semitism, like accusations of sympathy with terrorism, stop critical thinking dead in its tracks. Ultimately, these prohibitions on speech function not to prevent prejudice but to quell political dissent and silence debate.

Here we return to the question of the End of Theory. "Precarious Life" argues that the very things some have taken to signal theory's irrelevance -- in particular, 9/11 and its aftermath -- are actually the very events that make work of cultural criticism more imperative than ever. The same issues that Butler scrutinizes are those that supposedly sealed the fate of postmodernism. Perhaps instead they should be taken as an injunction to reinvest critique with the urgency and seriousness that may have dissipated in recent years. As Butler warns in her preface, the "foreclosure of critique empties the public domain of debate of democratic contestation itself, so that debate becomes the exchange of views of the like-minded, and criticism, which ought to be central to any democracy, becomes a fugitive and suspect activity."

Theory, Butler clarifies in our conversation, has been mistaken by many people to be a "position of permanent skepticism." Instead, she sees it as "nothing more than a critical interrogation of beliefs we already carry with us." It is a form of inquiry that does not deny the existence of the world but rather relates to it critically. "Theory is never fully abstract," she says, for "it is in the context of action that we have to think." In her words, theory is an "engaged form of reflection" that frequently "emerges in tandem with suffering."

At the end of the final essay Butler presents a modest proposal that may "reinvigorate the intellectual projects of critique" and "create a sense of the public in which oppositional voices are not feared, degraded or dismissed." She asserts that cultural criticism's task is to "return us to the human where we do not expect to find it," be that in New York, Fallujah or anywhere else. In other words, one must consider critically the areas that have been deemed unthinkable, debate that which is regarded as unspeakable, and grieve the lives relegated to the unlivable. Surely days like these demand more thinking, not less.

Shares