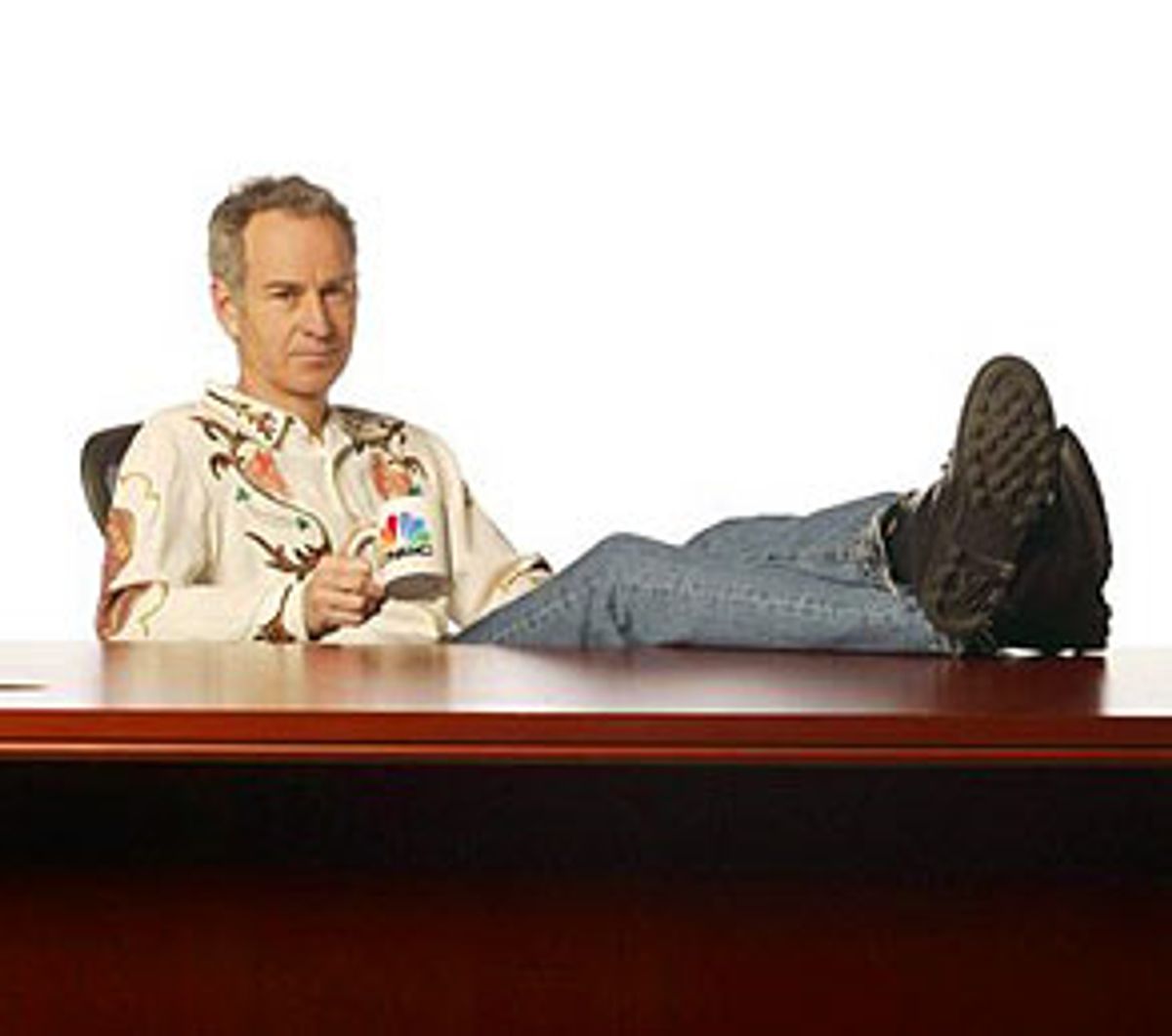

"You cannot be serious!" This phrase is repeated over and over during the first two broadcasts of "McEnroe," the new talk show hosted by tennis legend John McEnroe on CNBC (weeknights at 10 p.m.). It's the punch line of the first episode's opening skit, in which Will Ferrell leaves his dressing room and bursts onto the set of the finance show "Power Lunch," in character as Ron Burgundy from "Anchorman." It's echoed by guests and by the host himself. It's also the title of McEnroe's bestselling memoir, which came out last June.

But we've all seen the same footage of McEnroe yelling at the chair umpire a million times over, and when this, his most famous lament, is parroted incessantly on his show, it threatens to flatten out the appeal of this unabashedly temperamental man at a time when we should be rediscovering him as someone whose strengths transcend that grainy footage of a curly-headed tennis brat.

And then there's the problem of McEnroe himself, who understandably isn't sure how to walk the line between revealing the bite of his personality and playing the rah-rah, glad-hander role, which is flatly required for televised interaction with supersized celebrity egos. When juggling wide-ranging guests from Sting to Ferrell to members of Metallica, McEnroe demonstrates a difficulty with cutting people off or redirecting them. He's prone to indulging his own odd digressions, and often seems to wander off the pre-selected topics as the guests themselves, many of whom are probably more familiar than he is with the talk-show circuit, awkwardly try to return to their talking points. And during the first episodes, he seemed thrown by the teleprompter telling him to tease the next segment, and ended up mumbling the teaser like a moody kid anxious to kick somebody in the shins.

Still, for all of the obvious challenges that make an ornery presence like McEnroe commit tons of unforced errors in his first few episodes on the air, there are an equal number of promising qualities that make his long-term survival at least a possibility. As strange as it seems that someone as stubborn, sharp and easily bored as McEnroe would choose to venture into the realm of celebrity gab, these personality traits are exactly what give him a fighting chance. His dry demeanor is refreshing, compared to the typical giddiness and empty up-talk of most talk show hosts. He's interested only in what's interesting -- instead of listening to the same old cute anecdotes, he talks about sex with Sting and drug abuse with Lars Ulrich and James Hefield of Metallica. He's also remarkably quick on his feet and has a great sense of humor that's sure to come out more and more as he gets more comfortable with this new format.

Most important, though, he has a nice, direct way of tackling the obvious, whether it's positive or negative, in a way that other hosts would shy away from. "You're living legends and you still kick ass! That's not bad, right?" he blurts, like a thrilled kid, to Ulrich and Hetfield. And when he gets Green candidate Ralph Nader in the hot seat, he has the courage to repeat exactly what he knows Nader doesn't want to hear, but that the audience does.

McEnroe: Ralph, now, will you promise us one thing, though, that when push comes to shove, you won't let this guy Bush in again? Listen, I'm all for you, Ralph, but I'll give John Kerry a call, and what position do you want in the cabinet?

Nader: Come on! Did anybody ever buy you out?

McEnroe: Absolutely never. But this is sports. Your thing is a lot more serious than sports.

McEnroe is kind to Nader, but insists on trying to pull him out of the idealistic haze in which he refuses to distinguish between throwing a tennis match and altering the course of world history. When so many shows can hardly be viewed as anything more than the distribution arms of elaborate publicity machines that peddle stars as their products, McEnroe's ability to state his opinion and lob difficult questions immediately sets him above the typical exercise in brown-nosing that passes for a talk show today.

Of course, sometimes McEnroe's openness and comfort with his guests offers such an inside glimpse of the alternate universe in which wealthy celebrities exist, it can make you feel downright dirty.

McEnroe: I have one bone to pick with you, though. Because during that movie [Metallica documentary "Some Kind of Monster"] I noticed that at one point you sold some art at Christie's and made -- I'm not even gonna tell you how many millions you made, but if you go see the movie, you'll see this guy made a ton of money.

Ulrich: Do you feel that you're not credited enough for introducing me to Jean-Michel Basquiat?

McEnroe: You read right through me.

Ulrich: Every time I see John, within a couple of beers' time, it always comes up that I never give you enough credit for introducing me to Jean-Michel Basquiat, so I'll do it right now. John, thank you.

McEnroe: You made millions.

Ulrich: Tomorrow night will be on me.

Most stars are self-conscious about such talk -- and rightly so. We mortals don't necessarily want to know all of the advantages of being connected to every other powerful, high-profile human on the planet. While McEnroe's frankness is what gives his show the potential to be lively and unpredictable, he may have to scale back this honesty on certain fronts if he wants his audience to feel that they can relate to him -- whether that's an illusion or not.

Because no matter how direct and honest and real McEnroe might like to be, he still has to grapple with illusions if he wants to be successful in this realm. He'll occasionally have to feign enthusiasm for guests he's not that excited about, overpraise bad movies and plug crappy CDs. David Letterman does it with his tone; no matter how ridiculous his words might be, the sarcasm in his voice tells us not to take any of his gushing seriously. The challenge for McEnroe is to show interest in his guests without straining in a way that ultimately rings false, like, say, Rosie O'Donnell, who masked her bald contempt for guests with squealing and goofiness.

In several recent interviews, McEnroe has expressed confidence that his natural charms can keep viewers interested, but the truth is, he eventually has to develop a camera-ready alter ego, one that feels genuine but also functions more smoothly in difficult situations than a real human being possibly could. All of the best hosts, from Johnny Carson to Letterman, have created "Great and Powerful Oz"-style personalities that borrow on the strengths of the man behind the curtain, but have little to do with his weaknesses. Jay Leno's bad habits on-camera -- allowing guests to ramble aimlessly, pitching softball questions -- reflect his inability to inhabit a TV self that would provide an escape from his unrelenting urge to be a nice guy. Self-deprecation, a trait that McEnroe has said makes him likable, can be incorporated into his show, but if it's allowed to wander freely, it could pull the curtain open and reveal a flawed human who doesn't belong on TV. In his early episodes, this curtain flies open often.

Ultimately, McEnroe's success depends on his ability to craft a persona that transcends both the one-dimensional catchphrases and looping footage of past temper tantrums and the sticking points of a personality far too complicated to be reflected fully on the small screen. McEnroe is a quick study, but no amount of snappy wit and clever gags and talk show spackling from sidekick John Fugelsang will save him from the task of creating a character for himself, one that's far more comfortable inhabiting the small screen than the outspoken racket tosser we know and love could ever be.

Shares