When I found out the U.S. Coalition Provisional Authority had handed the governance of Iraq back to the Iraqis on June 28, two days earlier than planned, I was in the northern Kurdish city of Erbil eating a pizza. Though many hours had passed since the small ceremony in which CPA proconsul Paul Bremer handed the reins to the new Iraqi government headed by Prime Minister Iyad Allawi, the news took me completely by surprise. I had been up for hours, had driven across the city with a Kurdish driver and translator, and had made my way though half a pizza in a small but crowded restaurant called "Happy Time" without any sign that I had essentially been sleepwalking through a historic day in Iraq.

In a lot of ways, the lack of celebration shouldn't have shocked me in the least. For many Iraqis, a government headed by Allawi, who previously punched a time clock in the employ of both Saddam's early regime and later the CIA, has a distinct "Meet the new boss, same as the old boss" ring to it. Then, too, the outgoing CPA had essentially scooched Allawi into power past U.N. representative Lakhdar Brahimi's own candidate. Before my trip to Kurdistan, I might have assumed that the Kurds, who have been the United States' best ally in Iraq since the invasion began, would welcome a government that would seem to represent U.S. interests. But as I learned during my visit, the Kurds do not trust either the United States or their Arab neighbors to the south, and so they do not even begin to trust a U.S.-backed Arab government. These days, the Kurds aren't celebrating much of anything. They are waiting to see what the new government will mean for them, and whether it was worth giving up the relative autonomy they've enjoyed over the last decade or so.

I arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan around the middle of June, crossing the border from Turkey and making the five-hour drive to Suleymania in the east. Having spent close to nine months in Baghdad since Saddam's overthrow, I was interested in spending time in the Kurdish north during the transition to get a better sense of where the Kurds stand on the new Iraq. The road from the border switch-backed through mountains terraced into farmlands and dropped down into green and gold valleys where fat rivers rolled past villages and flocks of sheep. On a purely geographic level, Kurdistan has almost nothing in common with the rest of Iraq. In fact I had to remind myself I was in Iraq. A Kurdish man I met likened it to Switzerland. I'm pretty sure he had never been to Switzerland, but as comparisons go, it wasn't so far off the mark.

Suleymania is a midsize city, visibly untouched by the kind of violence that has marked just about every non-Kurdish city in Iraq. Like most of the Kurdish area, which became semiautonomous in 1991 when the U.S. implemented a "no-fly zone," Suleymania has proven to be quite safe for Westerners. It was the only place in Iraq I ever took a walk alone. (I met another American there, a privately contracted medic for the CPA, who told me he loved to walk around the crowded souk, or market, in shorts, in part as a way to encourage Kurds to wear shorts instead of the long pants that must be scorchingly hot in the summer. Probably a death sentence in non-Kurdish Iraq.) In Kurdistan, not a single U.S. soldier has been kidnapped or killed since the invasion. As far as I know, no Westerners at all have been kidnapped or killed in the region. Somewhere (the Army asked me not to tell where), tucked among the mountains, sits a modest resort hotel where soldiers get sent from other parts of Iraq for a few days of R&R.

The day after I arrived in Suleymania, the tiny CPA staff held a farewell press conference. I and the journalist I was traveling with represented the entire Western press corps. The press conference took place in a diminutive auditorium inside the soon-to-be-defunct CPA building. Before the conference began, I spoke with the press officer who told me he was worried that no members of the Kurdish press would show up. As it turned out, on the previous afternoon Paul Bremer had been in town for his own farewell moment, marked by a ceremony at the city's nicest hotel, the Suleymania Palace. But due to an apparent misunderstanding, the Kurdish press had become angry when they were shunted into a waiting room and denied what they considered appropriate access to Bremer.

As time went on and I met with Kurds in both an official and an unofficial capacity, I realized that what I came to think of as the "Bremer access incident" summed up the way the Kurds feel they've been treated by the CPA in general: stuck in one area, asked to be patient, denied access to the policymakers, and generally ignored.

This was all a bit of a revelation to me. I knew that the Kurds felt the United States had not been as good to the Kurds as the Kurds had been to it, but I had no idea just how pissed off they really are at the United States. They are really, really pissed.

On the day of the press conference, the Kurdish press did show up. One Kurdish reporter even asked, very politely, why the Kurds weren't getting more out of their friendship with the United States. (Another reporter was a bit more pointed, asking essentially, why the hell Muqtada al-Sadr, who's been nothing but trouble to the United States, had recently been invited to form a political party and participate in elections.) The almost-former head of CPA for Suleymania began with a reminder that the United States had gotten rid of Saddam -- the U.S. fallback answer to any question like that -- and then went on to enumerate a few pretty anorexic projects before launching into fallback answer No. 2: "In a democracy there are always compromises. Not everyone gets everything they want."

He was right. For strategic reasons, the United States could never have given the Kurds everything they wanted. But the Kurds still think that the United States has abandoned them. And they still can't believe it.

So the conference ended with politeness and even photo ops, but I felt acutely aware of the anger and frustration that pumped below the surface. The Kurds have been more open with their anger at the United States recently but they're not ready to show their cards yet, not ready to storm out of the press conference. They're waiting. With their long history of being stomped on, they are a very patient people.

So what exactly do the Kurds want that they aren't getting? Well, more than anything else, the Kurds want their own country. Kurdistan doesn't just look different from the rest of Iraq: The Kurds are a distinct ethnic group with their own language, culture, dress, traditions. And though the majority of Kurds are Muslim, they are significantly more secular than Muslim Arab Iraqis. (Of course generalizations always invite exception: I knew plenty of secular Muslims in Baghdad, and the Kurdish terrorist group Ansar al-Islam holds radically Islamic views.) In the post-WWII redistribution of the Ottoman Empire, the Kurds found themselves cut and pasted into a number of contiguous countries including Iraq, Iran, Syria and, mostly, Turkey. An estimated 20 million out of the 35 million Kurds worldwide live in Turkey, causing the Turkish government deep and ongoing anxiety. In the past, the Turkish government has done just about whatever it could to keep its Kurdish population from allying itself with Kurds in other countries or even, for that matter, affirming their own Kurdishness. Until 1991 it was illegal for Turkish Kurds to speak Kurdish.

For now, the Iraqi Kurds know they cannot push for independence. Turkey, fearing a destabilization of its own Kurdish population, would do whatever it takes to prevent such a move. The United States would probably have to back Turkey, an important ally in the Middle East. In the long run, pleasing the Turks is a much greater geopolitical asset that dissing the Kurds is a liability. Any move by the Kurds to break away would also, of course, threaten to incite a civil war within Iraq.

For now, the Kurds will settle for maintaining autonomy within Iraq and hope that a federalist Iraqi government would provide the in-country independence they're looking for. The problem is, the shape of the Iraqi government is still a big question mark. The Kurds are angry at the United States for not insisting on guarantees that the new Iraq would give them the same independence they had (courtesy of the U.S.) under the old Iraq.

Then, too, the Kurds feel as though they haven't been given their share of the reconstruction pie. Despite the safe conditions of the region, there is not a whole lot of rebuilding going on. And despite the lush-looking countryside, Kurdistan is desperately poor.

At the Suleymania press conference, I met Maj. John Hubert, a civil affairs officer in charge of overseeing projects for the region. I spent an afternoon with him and a few of the men he works with visiting a school that the military had built in a meager village about a half-hour outside the city. We drove to the village in two white armored SUVs, turning off the main road and onto a dirt track for the last half mile. We pulled up in front of the new school and got out of the air-conditioned vehicle into the smack-down heat of the long Iraqi summer. I was reminded, as I often am in Iraq, how much it must suck to be a soldier and wear all that body armor.

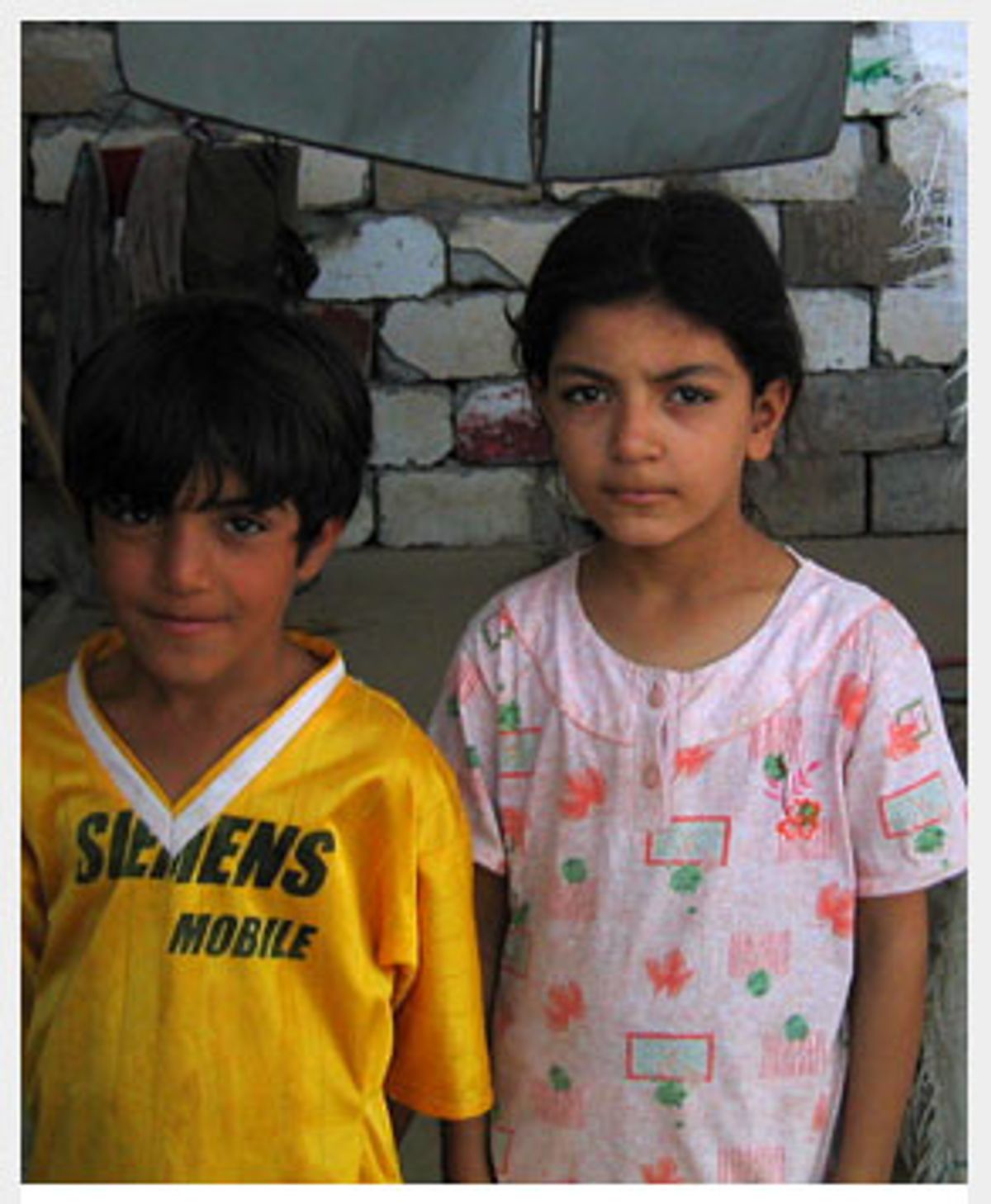

In mud dwellings opposite the school, women in long nightgown-type dresses (purple and magenta and turquoise) edged out to see what was going on and quick kids edged right past them. As one of the soldiers began walking down beyond the school to check out the area, a flock of domesticated geese claimed him as their leader. If you've never seen a flock of geese follow a heavily armed and armored soldier, you're missing out.

The school was not quite complete. Workers were finishing up with doors, windows, bathrooms. But Hubert gave us an intensely and justifiably proud tour. The one-story school had been constructed of cement and plaster into a wicket shape that wrapped around a courtyard. The old school, still standing, though barely, next door, showed just what an improvement the new one would be. It was a crumbling mess with one pit-toilet outhouse for the whole school. The village kids, kept outside the gates by the workers, shouted their approval along with the occasional "I love you" in English. (The "I love yous" were probably inspired by American TV and movies. In even the most desperately poor villages and neighborhoods of Kurdistan, TV satellite dishes rise like moons over mud and straw roofs.)

Hubert is one of those soldiers who make me feel that the military might, in fact, have more than a few good men. He is smart, thoughtful, driven and, above all, interested. But, though he clearly wants to help the Kurds, he doesn't have a whole lot to work with. Apart from the school I saw that day, he and his men were working on about 28 other projects, the small school being one of the largest. At the press conference, Hubert announced that the United States will spend $435 million in Kurdistan. It's only a fraction of the tens of billions that will be spent throughout Iraq, and it's hard to see a lot of tangible results. Nailing down the exact amount that will be spent on Kurdistan, and whether in fact the Kurds are getting the short end of American reconstruction dollars, is virtually impossible. But I got the feeling that for the Kurds, the perception of neglect trumps any statistics. In reference to proposed spending in Iraq, a Kurdish employee at the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs said, "George Bush claims 18 billion, 18 billion, 18 billion -- where is billions? Billions of illusions exist.")

Erbil, Kurdistan's largest city and my destination after Suleymania, is one of the poorest cities I have ever seen. All over the city open sewage runs parallel to sidewalks, and makeshift shanty towns hold what seems an impossible number of people. Given the fact that Erbil has almost as good a safety record as Suleymania (there have a handful of incidents targeting Kurdish politicians), it seems like a no-brainer that now would be the time to implement a lot of projects, while work in the rest of the country remains nearly untenable. The lack of aid is part of the reason the Kurds feel so frustrated with the United States. I get the impression that, as far as U.S. attention goes, the Kurds are suffering from the good-child syndrome. While the troublemaking violent kid (that is, the rest of Iraq) gets all the attention, the good child, the one we never worry about, gets passed over. (This is not to say that I feel in any way that the United States should pay less attention to the rest of the country or provide less support. I think we're doing a shitty job across the board.)

Erbil was home to a larger CPA contingency than Suleymania, but of course that, too, is now gone. The new U.S. Embassy, which will have thousands of employees in Baghdad, won't have a single representative in Iraqi Kurdistan. The only thing close will be the three U.S. Embassy representatives based in Kirkuk, a city now hotly contested by Kurds and Arabs. Kirkuk, with its surreal suburb of high-yield oil fields, has developed into a major flashpoint for Kurdish-Arab relations.

For generations, Kurds and Arabs have been wrestling for control of Kirkuk, which lies on the edge of the Kurdish region. Under Saddam's regime, the Kurds were forcefully ousted from Kirkuk (and other Kurdish-dominated territory Saddam coveted) in what is referred to as the Arabization program. Kurdish families were taken from their homes by Saddam's secret police and forced to leave the city, often without any of their belongings. Their homes were given to what Kurds still refer to as "10,000 dinar" Arabs who moved into the city. Ten thousand dinars represents the amount of money Saddam paid Arab families to relocate to Kirkuk and other Kurdish towns. In today's Iraq, 10,000 dinars is worth about seven bucks. But during the height of Saddam's Arabization program -- until the sanctions drove inflation through the roof -- 10,000 dinars equaled around $30,000.

Under Saddam, Kirkuk was not part of the Kurdish region (which, with U.S. protection, had its own government, militia and even currency). Now Kurdish officials, anxious to reclaim Kirkuk, are urging -- even compelling -- Kurds to return to the city en masse.

"We don't accept that Kirkuk is not part of Kurdistan," the governor of Erbil, Nawzad Hady, told me. I had gone to meet with him in his office inside a well-guarded building in Erbil's center. One of the governor's many assistants led me up to the second floor, past some file-choked offices and through a series of increasingly well-decorated waiting rooms. In each room, a dozen or so men sat on couches along the walls smoking and drinking tea from fat hourglass-shaped teacups. After 45 minutes of drinking tea, I was ushered by another assistant into the governor's inner office, a long room decorated with new-looking upholstered furniture and lush carpets. Hady emerged from behind his raft-size desk and greeted me. We sat opposite each other with his translator in a chair between us while his assistant hovered, furiously taking notes.

Hady told me that Kurds must return to Kirkuk and the "10,000 dinar" Arabs must leave. (Other Arabs, families who have lived in Kirkuk for generations, do not face the resentment that the "10,000 dinar" Arabs do.) The Kurdish government has been handing out leaflets and using television campaigns, telling families to return. And Hady confirmed that in some cases, families have been paid $3,500 to go back to Kirkuk. At least a portion of the money to help families came from a U.N. fund, established before the war to build housing for refugees in Erbil. But the project fell apart, and with no sign of the United Nations' return, the government began using the money as aid and incentive for refugees to go back. Within his own government, Hady said, he directs all employees of the Erbil government who are originally from Kirkuk to move to that city, where they will be guaranteed an equivalent job and salary in the government there.

This hasty population redistribution program is as much about the future of Kirkuk as it is a question of reclaiming the past. Kurdish officials, including the governor, told me they intend to press for a referendum in which residents of Kirkuk will decide whether the city becomes reabsorbed into the Kurdish region. If the current Iraqi government refuses to allow Kirkuk's future to be decided by vote, Hady said, the Kurds will opt for deciding its future by force. Kurds may make up only 20 percent of Iraq's population, but their armed forces, or peshmerga, are nearly 100,000 strong -- bigger than all other Iraqi militias and armed forces combined. In short, the Kirkuk question could destroy the cobbled-together new government of Iraq.

Last week, Allawi declared that a "special status" might be granted to Kirkuk to take into account its diverse population. At this point, it's anyone's guess what "special status" will mean in practice. The Assyrian International News Agency quoted Allawi on Friday as saying that a countrywide abolition of militias would include Kurdish peshmerga. "Some of the Kurdish peshmergas will be recruited to the Iraqi army while some of them will be added to Iraqi police force." According to the agency report, Allawi added that the remaining peshmerga would lay down their arms and begin civilian life or would be retired. When Allawi first announced his intention to disband militias in June, a furious Kurdish response forced him to back down. I can't imagine the Kurds would ever agree to relinquish what is essentially their own army, especially when their future status remains unclear. If Allawi tries to force a disbandment, the results could be very bloody.

(It's interesting to note that Erinys, the South African security firm contracted to protect the oil infrastructure across Iraq, employs over 95 percent Kurds to guard Kirkuk's oil fields. Most of them are former peshmerga.)

Kurdish designs on Kirkuk have become a big problem, not just for the new Iraqi government, but for the Turkish government, which is apt to wig out anytime it perceives the Kurds to be making a move of strength. A little over a week ago, the Turkish Foreign Ministry issued a warning to the effect that no "involved party" should attempt to change the demographic makeup of Kirkuk before its final status is determined.

These days, the Kurds don't have a lot of friends in the region. But that may be changing. In a recent article in the New Yorker, Seymour Hersh described an increasing Israeli presence in Iraqi Kurdistan. "Israeli intelligence and military operatives are now quietly at work in Kurdistan, providing training for Kurdish commando units and, most important in Israel's view, running covert operations inside Kurdish areas of Iran and Syria," Hersh wrote.

An alliance between the two makes a lot of sense. For the Kurds, it provides a powerful ally, friendly with the United States, to train their commando units for deployment against potential Iraqi or other Arab enemies. For the Israelis, it allows them to infiltrate agents into their arch-nemesis, Iran, as well as hostile Syria. Certainly the Israelis would be delighted with the creation of a friendly, independent Kurdistan.

Israeli officials, not surprisingly, denied the story. The U.S. State Department refused to comment, but a senior CIA official confirmed Hersh's report. After the article came out, Kurdish leaders vehemently denied its veracity, calling it "baseless" and a "vile campaign against the Kurds." The denials were so adamant that they brought to mind my mother's favorite Shakespearean phrase: "Thou doth protest too much." For what it's worth, when I was in Kurdistan I asked Kurds whether they knew about an Israeli presence, and none said they did.

On a brutally hot day (every day in Iraq's summer can be categorized as "brutally hot" "extremely brutally hot" or "really very extremely brutally hot") I took a trip to Kirkuk. By coincidence, it was July 1 -- the original date for the first day of Iraqi self-governance. I made the one-hour drive from Erbil in the company of a Kurdish driver and translator and a fellow reporter. In the course of planning our trip to Kirkuk, we had received all sorts of advice as to how to stay safe. One Kurdish man we spoke to insisted that we should travel only in the company of some armed peshmerga. Another Kurd suggested we hire one of the many Western security companies working in Iraq. We would travel in a convoy of armored SUVs with a small cadre of very heavily armed men who would dress us in bulletproof vests and loosely encircle us whenever we got out of the car to interview someone. (The cost would have been at least a thousand dollars for the day). Some people tried to strongly discourage us from going at all. Most Westerners we met -- CPA employees concluding their jobs or embassy employees commencing their jobs (in some cases those were one in the same) were on "lockdown" during a number of days leading up to and following the transition of power, in anticipation of heightened violence. This meant no leaving their fortified compounds or secured hotels.

During an informal conversation with the only other American woman I met in Kurdistan -- a young, dedicated Southerner working for a Christian NGO -- I asked what precautions she took when going to Kirkuk. "Not nearly enough," she said. "I mean, I carry a nine millimeter, but..."

In the end, we decided that low-key would be safest. We started out early in the morning in a new model BMW. ("I think BM is a very good car," our translator said. We advised him to consider not dropping the "W" when talking to Americans.) The road ran flat and straight though the countryside. Uneven mounds of recently harvested wheat punctuated the fields along the road. We sped along, passing other cars, tractor-trailers, and pickup trucks. In the back of many of the pickups, kids -- boys in T-shirts and sweatpants and girls in granny-nightgown-type dresses -- stood up in the beds and bobbingly clung to the truck cabs.

Other advice I received before the trip: If I had to go to Kirkuk, I should at all costs avoid the Arab neighborhoods. I would be safe in Kurdish neighborhoods, but I would be as good as dead in Arab neighborhoods, Kurds told me. The advice to avoid Arab neighborhoods stemmed, in part, from the ongoing attacks on Westerners by Arab groups: the kidnappings and assassinations of contractors and aid workers, the ambushes against U.S. troops.

The violence has amped up Kurdish mistrust. Throughout Kurdistan, peshmerga man an endless number of checkpoints. Kurds mostly get waved through, while Arabs, my translator told me, almost always get carefully searched. Precautions like this may have helped keep the region safe, but it's a kind of racial profiling that doesn't do much for Arab-Kurdish relations.

Hassib Rozbayani, who holds the title of assistant mayor for resettlement and compensation for Kirkuk, lives in a single-story home a mile or so from what had just recently been the CPA compound in Kirkuk. Now the compound is being used by representatives of the U.S. and British embassies and their support staff (the ratio is something like six embassy employees to 100 support staff). I spoke to Rozbayani at his home in Kirkuk shortly after we arrived in the city. Weeks earlier, July 1 had been declared a national holiday in celebration of the hand-over of the government. The premature hand-over made the day a little anticlimactic, but it remained a holiday nonetheless and all government offices were closed. When my translator reached Rozbayani on his cell phone, he generously invited us to come by his house on his day off. We got a little lost finding his house and stopped to ask directions from a soda vendor on the side of the road who pointed us in the right direction. Our driver, Dashti, peeled out and U-turned toward the correct street. Throughout that whole day, he drove like a cop in a car chase. Though we didn't venture out of Kurdish neighborhoods, having a couple of Westerners in the back seat of the car was risky, to say the least. And so he did whatever necessary to avoid being stuck in traffic, turning down side streets and alleys anytime we hit congested roads. It wasn't exactly comfortable, but it was comforting.

When we reached Rozbayani's house, a guard out front (holding a Kalashnikov, the weapon of choice for guards all across Iraq) went to announce us. In the last year, a number of Kurdish political figures have been assassinated in Kirkuk. Having an armed guard goes with the territory. Rozbayani led us into the living room, where his own rifle leaned against the couch. He sat down next to it and began chain-smoking cigarettes. With his longish wild hair, he looked more like an aging rock star than a politician. The city power had gone off and, as he talked, the lights of the living room dimmed and rebrightened with the variations in the generator.

Rozbayani said that right now in Kirkuk there are 70 refugee camps of varying sizes. Despite the money going to some returnees, most Kurds have returned with almost nothing. The situation in the camps is very bad, he told me, but he, too believed the Kurds had to reclaim Kirkuk. He was angry at the CPA for what he referred to as "negative support" of the refugees. Though he had asked repeatedly for assistance, the CPA had refused to provide any aid at the camps, he said. In some cases, Rozbayani said, U.S. soldiers had expelled the refugees from camps and arrested those who refused to leave. He firmly believed (as did Hady, Erbil's governor) that the United States had been pressured by Turkey to discourage the Kurds from returning to Kirkuk. Other Kurds I spoke to who worked with the CPA on the refugee question said that throughout its tenure, the CPA promised help and asked for patience. A CPA staffer I spoke to declined to comment. Given the volatility of the issue, it seems clear that the CPA is doing what it can to placate both sides (without really pleasing either).

Understandably, Arabs in Kirkuk don't want or intend to relinquish their homes. But Arabs have been forced out from homes in Kirkuk and other rural areas of Kurdistan. Inside Kirkuk, ongoing harassment campaigns by both sides keep tensions high. Kurds fire shots at Arab homes, Arabs fire shots at Kurdish refugee camps. Assassinations have become a daily occurrence. Arabs have said that if the Kurds push too hard, they will fight back. They warn that Arabs from all over Iraq, including Muqtada al-Sadr's supporters in the south, will come join the fight.

In Kirkuk's current situation, there are no winners. Kurdish families return to Kirkuk every day hoping to effortlessly reclaim their former lives. Instead, they end up slogging it out in one of the miserable refugee camps throughout the city.

The Kirkuk sports stadium sits in a garbage-strewn, desolate corner of Kirkuk. As we approached it, I noticed a series of hand-painted signs along the road that depicted a young girl throwing her trash in a garbage can -- the remnants of a long-abandoned anti-litter campaign.

Jerry-built shelters made of mud, straw, flattened cooking-oil cans and empty rice sacks surrounded the stadium. Shallow ditches of raw sewage linked the houses and scrawny, nearly featherless chickens pecked at the edges of the sewage in search of something edible.

We parked in the shadow of the stadium walls. Refugee families had made good use of the stadium, building shelters against its curving walls. Some curious kids and adults came to greet us, but many were sleeping off the intense afternoon heat or working in fields outside the city. Then, too, a lot of missing husbands and fathers had been killed years ago in Saddam's murderous anti-Kurd campaigns.

We spoke to a woman who had returned to Kirkuk right after the fall of Saddam. It seemed most of the refugees in that camp had arrived not long after the end of the war, anxious to get back to their former city. They had imagined they would receive help from the United States and from their own Kurdish political parties, but they had received virtually nothing. (The woman said that the Americans had come once and given out some dishware. They made a list of needs and never came back.)

Bad as the conditions were at the stadium, the Kurdish refugees there are better off than those living in other Kirkuk sites where canvas tents act as the only shelter. Though the refugees have chosen on their own to return, I can't help thinking that they have become the demographic pawns in a struggle over oil and power and real estate.

Those refugees, like all other Iraqi Kurds, believed the invasion and Saddam's ouster would mean a tremendous step into prosperity. Make no mistake, the Kurds are grateful to be rid of Saddam. Talk to any Kurd about the United States and the first thing you're likely to hear is how happy they are that Saddam is gone. But with their future in the new Iraq so uncertain, and their old pal the U.S. so unreliable, the Kurds feel more isolated than ever. Control of Kirkuk ("the city of black gold," Rozbayani called it) represents their best chance for a strong position in the new Iraq. "If Iraq doesn't return Kirkuk, it could cause civil war," Hady told me that afternoon in his office.

A Kurdish-American I met doing business in Iraq put it another way. "Trust me," he said. "They are going to the gym. They are getting ready."

Shares