"The Bourne Supremacy" is such an incredible piece of direction it's a pity the material -- Tony Gilroy's adaptation of Robert Ludlum's novel -- doesn't have the depth to stand up to it. The director, Paul Greengrass, does nothing rote. The plot -- the amnesiac former CIA assassin Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) is framed for the murder of CIA agents about to uncover a mole -- is espionage pulp. Greengrass keeps you off-balance throughout. When the fight scenes and car chases arrive, there's no telling, from shot to shot, what we will see next or how we'll see it.

The first movie in this franchise, Doug Liman's 2002 "The Bourne Identity," was notable for not treating its violence as mindless action-movie kicks. It felt like an entertainment made by and for adults. Greengrass goes even further, making the violence hard and pitiless. Working with cinematographer Oliver Wood, Greengrass shoots the fight scenes and chases so close in that we see some moments almost as a blur. The editors, Richard Pearson and Christopher Rouse, break those sequences up into quick jagged shots that key us up and keep us hyper-alert. The world is being broken into bits of information, and we look hard at the screen to take it in.

The approach could have resulted in the usual visual gibberish that defines contemporary action moviemaking. You can always tell what's going on in "The Bourne Supremacy," where characters in a fight or a chase are in relation to one another. Greengrass and his production team make you feel as if you're in the middle of the mayhem with them. The violence isn't divorced from pain. When, in the middle of a car chase, Bourne tries to match what he reads on a map to an exit sign zooming by, we see the sign as a shaky indecipherable mass -- we might be looking at some abstract video project.

Toward the end of the film there's a car chase through the streets of Moscow. If you've never been in a car crash, I hope watching this scene is the closest you ever come. It's close enough. How can there even be such a thing as a car chase worth watching at this point in the movies? But the sudden shots of cars looming up towards the camera to smash the small taxi Bourne is driving, the shots of cars forcing their way through spaces that look no bigger than slivers, leave you feeling very unprotected. "The Bourne Supremacy" has been made to puncture the detached delectation of thrills that is usually the only thing required of us at action movies. Greengrass returns espionage fiction to one of its honorable functions, making it a barometer of our sense of violence in the world.

In "The Bourne Identity" it often felt as if we were watching the movie from inside Franka Potente's skin. As Marie, the student who helps Bourne and winds up running for her life, Potente presented the camera with a face so open that it provided her with no protection from the violence she was seeing -- not just for the first time, but up close. She returns briefly here, and though the focus is on Damon, Potente is one of a trio of actresses who damn near bring the movie to a halt when they appear.

Along with Potente, Julia Stiles, as one of Bourne's former CIA handlers, and Oksana Akinshina (the star of Lukas Moodyson's "Lilja 4-Ever"), as the orphaned daughter of a couple Bourne murdered for the CIA, offer up moments of raw terror and grief that humanize the material. When these actresses are on screen, you can't shrug the potential for harm coming to them as mere action-movie convention. Potente exits the movie in a haunting, mournful, deeply romantic and dreamlike image that Brian De Palma would have been proud to put his name on. Stiles, the most fastidious young actress in movies, shades in her usual confident control with a layer of fear that is unlike anything she's done before. And Akinshina, who says maybe 10 words and spends most of her scene simply sitting in front of Damon, offers a small, vibrant lesson in what movie acting is all about. She turns the camera into a receiver to pick up the impulses and emotions coursing back and forth beneath her skin.

They certainly show up Joan Allen as the CIA officer who suspects Bourne of murdering two of her agents. When did watching Allen become a drag? It's not that she's bad here, but the pliancy and verve she showed in early performances like "Manhunter" aren't in evidence. Allen was once the type of actress to inspire behavior like that of one film critic I know who snoozed through Oliver Stone's "Nixon" yet disciplined herself to wake up whenever Allen, as Pat Nixon, was on screen. You could sleep through many of Allen's recent performances and not miss much. It wasn't until halfway through the movie that I realized I was supposed to be rooting for her character. Her crisp officiousness is what usually awakens our antiauthoritarian impulses in movies.

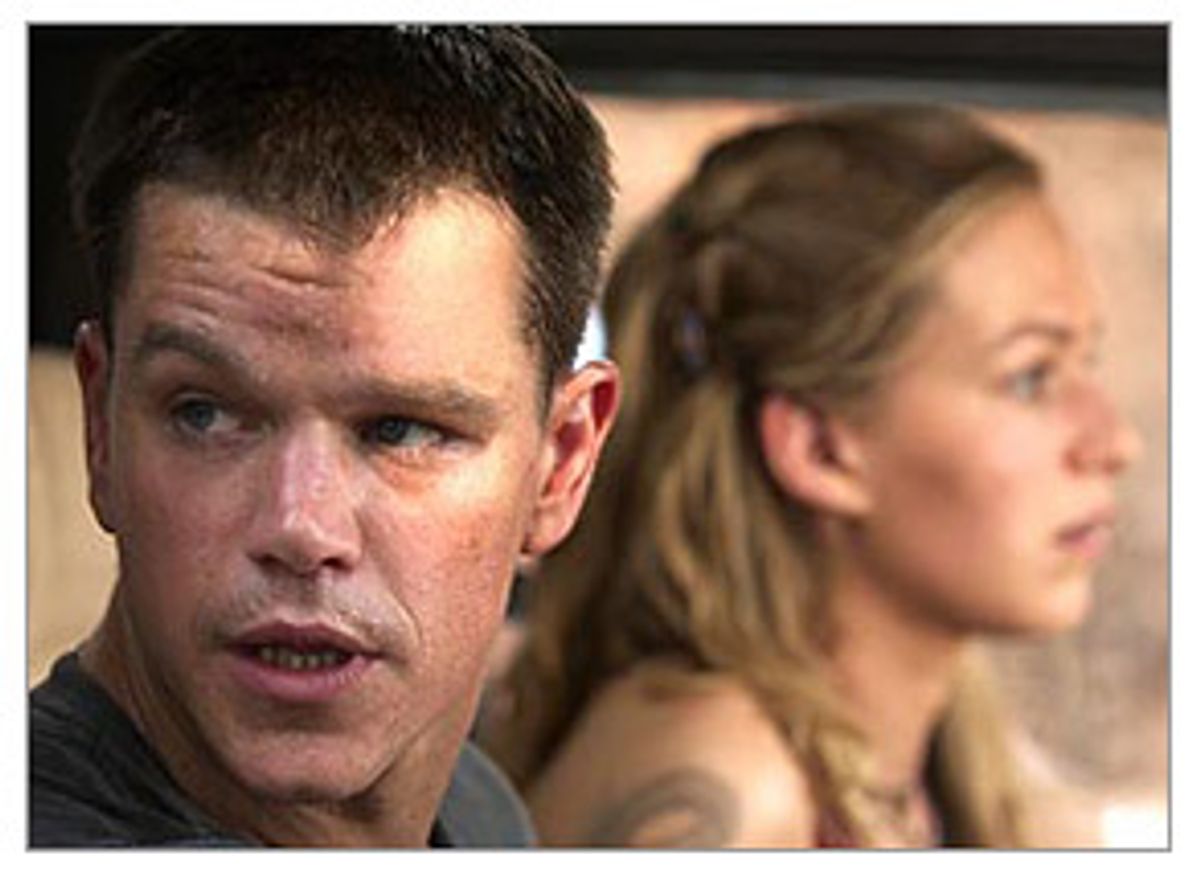

Some of Damon's physical work is very good. In one fight scene, after Bourne kills a former colleague, there's a moment where he seems to awake from a trance and quickly pushes himself in revulsion from the corpse. It's a small gesture that conveys the senses of a man who has been trained to kill without thinking. But playing a man blocked off from his past, Damon is blocked off from the audience. His beetle-browed conception of the role isn't engaging enough to hold the center of the movie. There's too little sense of the fear beneath his exterior or, conversely, the poignancy of a man who has had fear conditioned out of him. It's not that Damon is incapable of emotion: His comic openness was one of the best things in the Farrelly Brothers' sweet and underrated "Stuck On You."

The problem with "The Bourne Supremacy" is that Greengrass' direction can't find a corresponding depth or soul in the material. The movie is an entertaining, well-constructed spy story (though not as satisfying as the first film -- perhaps because it's not as simple) but, apart from the scenes with those three actresses, it doesn't scar you the way a first-rate thriller can.

Greengrass is working as a hired hand here, as he wasn't on his last film, "Bloody Sunday." That 2002 film, the story of the 1972 peace march in Derry, Northern Ireland, in which British soldiers firing on the crowd killed 13 people, is one of the greatest political movies ever made. Working in the style pioneered by Gillo Pontecorvo and Costa-Gavras, a fictionalized account of real events shot in a semi-documentary style, Greengrass came close to outstripping the work those directors did in "The Battle of Algiers" and "Z." At the least, he equaled them. Greengrass set up the tragedy of the Bloody Sunday massacre so that we see the disaster looming, feel the unavoidable clash of marchers and British soldiers, and feel powerless to stop it. Using handheld cameras yet never sacrificing clarity, Greengrass captured better than any filmmaker I've ever seen what it feels like to be caught unawares in the midst of unfolding chaos. There were moments in "Bloody Sunday" when I forgot I was watching a movie.

There is no way for a director to make a movie as engaged and immediate as "Bloody Sunday" every time out. It would exhaust him as much as it would us. "The Bourne Supremacy" is Greengrass' attempt to transfer his gifts to mainstream entertainment. As a piece of craft, and with the exception of "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," it's miles beyond any studio film this summer. It's a terrific piece of direction and yet it doesn't provide a worthy enough outlet for Greengrass. Let's hope he finds those outlets, finds a way to personalize his commercial projects. He's too fierce a talent to waste.

Shares