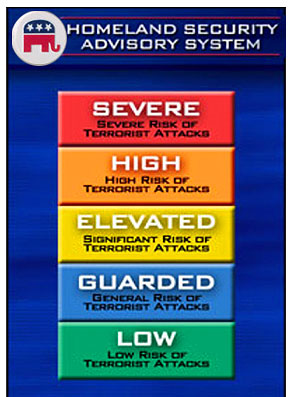

The fog of war has descended over the campaign. Within 72 hours after the Democratic Convention ended, the Department of Homeland Security declared a new terror alert, jacking up the color-coded level from yellow to orange, verging on red. The cause, the government reported, was that the computer of an al-Qaida operative captured in Pakistan contained precise information about threats to five financial institutions in New York and Washington.

Then additional information was released: The intelligence was mostly three to four years old (was the World Trade Center in this latest batch of targets?), al-Qaida’s surveillance of U.S. buildings had been mostly conducted through the Internet and other “open sources,” someone had opened the computer file again in January of this year for uncertain reasons, and Pakistani officials said that the captured material indicated no new al-Qaida planning.

The effect of the alert has been to throw the presidential campaign into turmoil and momentarily freeze it. John Kerry decided to accept the administration’s explanations and timing at face value. He could not be seen as veering into an Oliver Stone script, flailing at shadows of paranoia. His critique of Bush’s war on terrorism must be made with iron discipline, based on the facts at hand, not the suspicions in mind. Yet other Democrats have felt free to voice their views that the administration is using the situation for political advantage. The steam puts additional pressure on Kerry, who has to hold fast.

In part, the level of partisanship has increased because of the clumsy performance of Tom Ridge, the secretary of homeland security, who turned the alert announcement into a political rally. “We must understand that the kind of information available to us today is the result of the president’s leadership in the war against terror,” he said on Aug. 1. Several days later, Ridge held another news conference, at which he declared, “We do not do politics at the Department of Homeland Security.” With that the alert rose to the risible.

Whether planned politically or not, the alert exposed that for Bush terror is the irreducible basis of his campaign. And while it starkly elevated his profile as the “war president” again, it also revealed indirectly the vacuum of his second-term program (i.e., that his hard-right issues are insufficient to appeal to a national majority), his weakness on the realities of homeland security, and his desire to smudge the history of his inaction leading to 9/11 and of his responsibility for the deterioration of the situation in Iraq.

The widespread cynicism about the latest alerts, which may have no grounding, is a product of Bush’s intense politicization of national security, his long record of misleading statements about almost every aspect of the Iraq war — from weapons of mass destruction to the connection between Iraq and al-Qaida — and his well-chiseled image as a decisive leader worthy of Mount Rushmore, which is belied by the 9/11 commission report’s support of every charge in former counterterrorism chief Richard Clarke’s account of frustration.

The 9/11 commission report is a devastating and irrefutable record of Bush’s passivity on terrorism, beginning with his first act: the demotion of Clarke. The report documents that the administration “was not ready to confront Islamabad” on Pakistan’s support for the Taliban or to “engage actively against al Qaeda” and that it “did not develop new diplomatic initiatives on al Qaeda with the Saudi government.” Bush told the commission that the Aug. 6, 2001, President’s Daily Brief, “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.,” was “historical in nature,” though it contained current information. And, the report said: “In sum, the domestic agencies never mobilized in response to the threat. They did not have direction, and did not have a plan to institute.” The administration’s neoconservatives, such as Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, are depicted as dismissive — Wolfowitz opposed retaliation for al-Qaida’s attack on the USS Cole as “stale” — and obsessed with Iraq as the source of all terrorism.

Bush’s campaign must try to blur memory of his history. When Kerry seized upon the commission’s recommendations, Bush reacted a week later by endorsing a new national intelligence chief. But he would give this new post no control over budget, no White House office, no power over personnel and no authority over intelligence operations. Once again, he appeared to be acting only on political motives.

In the meantime, various bills for homeland security languish before Congress, neglected by Bush. His paltry $46 million proposal for port security, for example, is more than $1 billion short of what the U.S. Coast Guard says is required. On port security, 10 Democratic amendments have already been defeated while Bush has slept. He prefers that the money be appropriated for more tax cuts skewed to the upper bracket.

Bush is haunted not only by the ghosts of his own past but by the ghosts of other presidents past. While he attempts to redeem his father’s political fall by avoiding his mistakes, his effort at reversal is creating a similar estrangement from voters. The elder Bush won his war against Iraq and withdrew without toppling Saddam; his ratings were then at their peak. But his obliviousness to economic circumstances undermined the heroic image. Lyndon Johnson had an ambitious domestic agenda backed by a landslide electoral mandate. But he squandered it in the Vietnam quagmire, and his political credibility undermined his party’s for a generation. Now, Bush’s faltering credibility is tearing at trust in U.S. national security. Perversely, his campaign must exploit the fears, real or not, that his failures have helped engender. For him, the campaign is not a war of choice, but of necessity.