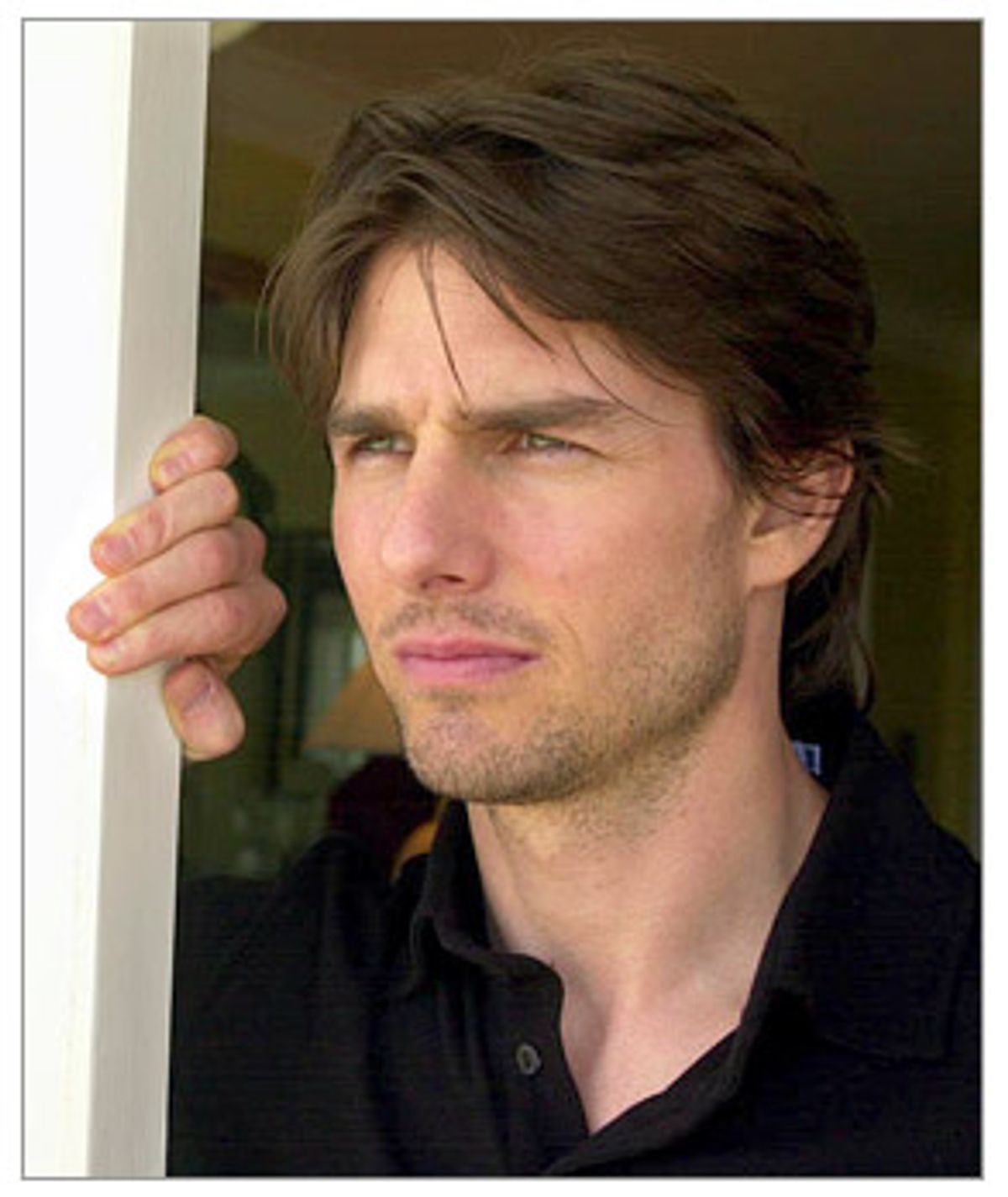

Despite what any of us may think of Tom Cruise, we've all had to get used to seeing him two or three times a year. At first because he was in those big hit movies that you went to because everyone else did ("Risky Business," "Top Gun"), then because he was working with directors and actors whose work you wanted to see.

Martin Scorsese's "The Color of Money" marked the beginning of Tom Cruise's being taken seriously. Without that movie, he very likely would have never worked with the likes of Dustin Hoffman, Oliver Stone or Stanley Kubrick. Cruise didn't seem out of place in "Rainman" or "Eyes Wide Shut," though, mainly because everything else in them was lousy, too. And sometimes he even seemed right for a role. In Stone's "Born on the Fourth of July," Cruise's particular self-involvement as an actor dovetailed with the self-involvement of the movie's subject, paraplegic Vietnam vet Ron Kovic.

But then there came times when Cruise was up against actors at the top of their game. He was like a pompadoured mosquito taking the focus off Paul Newman in "The Color of Money." And in his climactic scene in "Magnolia," crying over his dying father, played by Jason Robards, I almost felt sorry for Cruise; there he was, shaking and crying and emoting, and Robards, playing comatose, completely outacted him.

At a certain point -- maybe because I stopped expecting anything from Cruise -- he stopped seeming so annoying. He worked so hard in "Jerry Maguire" that he almost succeeded in making the character believable. At the least, he put himself in the service of the movie, and his conviction that it was worth doing (whether it was or not) marked one of the only times Cruise seemed like part of a team rather than a grandstander. In "Mission: Impossible," he was well used as something like a human action figure. Brian De Palma's film was an essay on the pride of being a professional in a faceless corporate world, and there was something ironic about having a star who had seemed to embody the facelessness of current movies at the center of it. By using Cruise as a character who represented a dedication to craft as the enemy of corporate anonymity, De Palma was being both sly and subversive -- using Cruise as a weapon against the studio suits who adored him.

Cruise is, of course, hugely famous and popular and rich, but to those of us for whom the word "star" still connotes something both mysterious and identifiable, Cruise has never seemed like one. He's a virtual star, a cipher star. His specialty has been a sort of vacuous intensity, characterized by glaring eyes and slight, cocksure nods of the head as he delivers his lines, usually with the ghost of a smirk on his face. Cruise's acting is all display; he doesn't connect with the people sharing the screen with him. There's no give-and-take, none of the sense of actors discovering each other, playing with each other, challenging each other.

Nothing can be pinned down as the Tom Cruise persona -- but that is not a sign of versatility (as it is with, say, Jeff Bridges or Gene Hackman, actors who disappear into their roles). When "Tom Cruise" comes to mind, you might, on a generous day, think hardworking, earnest, not particularly flashy. Words that could be applied to any diligent, nondescript person in almost any conceivable profession, and thus not the words we associate with being a movie star. What movie star could you compare Tom Cruise to? Every potential correlation falls short. Johnny Depp, because he was a teen idol who proved himself a serious actor? No, because Cruise has never had anything like Depp's wild-card streak, his dreamy ardor. Gary Cooper, because, like Cruise, he was an all-American straight arrow? No, because the young Cooper in a picture like "Morocco" was lithe and sexy -- before Frank Capra wrecked all that with "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town." (The comparison for Cooper would be Kevin Costner in "Bull Durham" -- and then in everything else.) Robert Redford? Well, Redford has been almost as dull as Cruise. But he has also managed a nice ironic streak; think of the pleased look on his face in "All the President's Men" when he gets a source to inadvertently reveal information over the phone; or the moment in "Barefoot in the Park" when, after an evening of unpalatable ethnic cuisine, he tentatively admits, "My teeth feel soft." That seems beyond Cruise -- and Cruise has never approached the self-examination Redford brought to his golden-boy persona in "The Way We Were."

The real comparison would be to manufactured idols like Troy Donahue, except that Donahue never commanded any respect (even though he managed to turn up in a couple of American classics, Douglas Sirk's "Imitation of Life" and Francis Ford Coppola's "The Godfather, Part 2").

So while there are precedents for separate bits of Tom Cruise's career, there's no precedent for the whole. And where is that career going now? After a while, it was easy to take Cruise for granted, not to expect much of him but to know that you were going to see him on-screen two or three times a year -- which translates usually to 10 major magazine covers and two dozen TV talk shows. He's become an inevitability, like the change of seasons or the garbage pickup.

But lately, it's been harder to take Cruise in stride, perhaps because he's decided, understandably, that the days of youthful roles are coming to a close and the time has come to demonstrate his authority. And this is a problem.

In "The Last Samurai," he failed in the most basic way as a hero of battle: He simply didn't have the command to make you believe that men would willingly follow him. In the new thriller "Collateral," Cruise plays his first out-and-out bad guy, a hit man who hires Los Angeles taxi driver Jamie Foxx as his chauffeur for the dusk-to-dawn schedule of murders he has planned and then precedes to force Foxx into his schemes. It's a simple, promising premise for a quick, nasty noir that director Michael Mann inflates into one of his pieces of designer existentialism. Mann might be fooling himself that he's upsetting the audience's expectations with a daring change of pace for Tom Cruise. And not only is Cruise thoroughly nasty but, with his hair in a salt-and-pepper rinse, he's shed his classic pretty boy looks more aggressively than ever before.

It backfires, partially because it looks like a kid playing dress-up and reminds you of the perpetual callowness of Tom Cruise. But the hair and the silver-gray suit Cruise wears also appear to be intended an homage to Lee Marvin in John Boorman's "Point Blank" (1967). What was Mann thinking? When an actor lacks menace and authority, as Cruise does, the last thing you do is compare him to Lee Marvin, who was able to hold the screen often doing little apart from the soft snarl in his voice.

Better actors than Tom Cruise are put at a disadvantage when they have to play a conceit rather than a character. And -- brother! -- is Cruise's character ever a conceit. He represents the chaos that Foxx has tried to keep out of his life and, in the movie's simplistic pulpy terms, the obstacle sent to show Foxx how to be a man. That's not just a dumb idea but, as it's worked out in "Collateral," an offensive one. Jamie Foxx is so good here you resent the idea that Cruise can teach him anything. "Collateral" opens with a scene between Foxx and Jada Pinkett Smith that is one of the reasons you go to the movies. The rapport between them, the actors' rhythms and responsiveness, is so natural that you resent it when her story is dropped as Cruise comes in. But it has to be. It's embarrassing enough for Cruise to act against Foxx; acting against Foxx and Smith would wipe him off the screen.

Besides, just how inescapable are the violent vagaries of the universe if they are embodied by Tom Cruise?

"Collateral" may be the latest move in Cruise's strategy of showing himself ready to move onto mature roles. And it shows why this new stage of his career may leave him more exposed than ever. Cruise may not have a recognizable persona (ever seen a comic do a Tom Cruise impression?), but there is something that characterizes him: a lack of believable experience. What could Tom Cruise reasonably play? He seems too aware of his star status to disappear into the role of an ordinary guy. Too stiff to play comedy. Not possessed of enough reserves of self-awareness to play a man examining his own life. Cruise, it would appear, will glide into the role of elder authority figure and, like Clint Eastwood, he may become more respected, the duller he gets. (God help us if he starts directing.) But for that to work it will mean ignoring who Tom Cruise still appears to be. In the third decade of his film career, Cruise still radiates the luck of the cute boy in high school who has managed to hold on to his looks and who has yet to be tested in a way that would make him a believable adult.

Shares