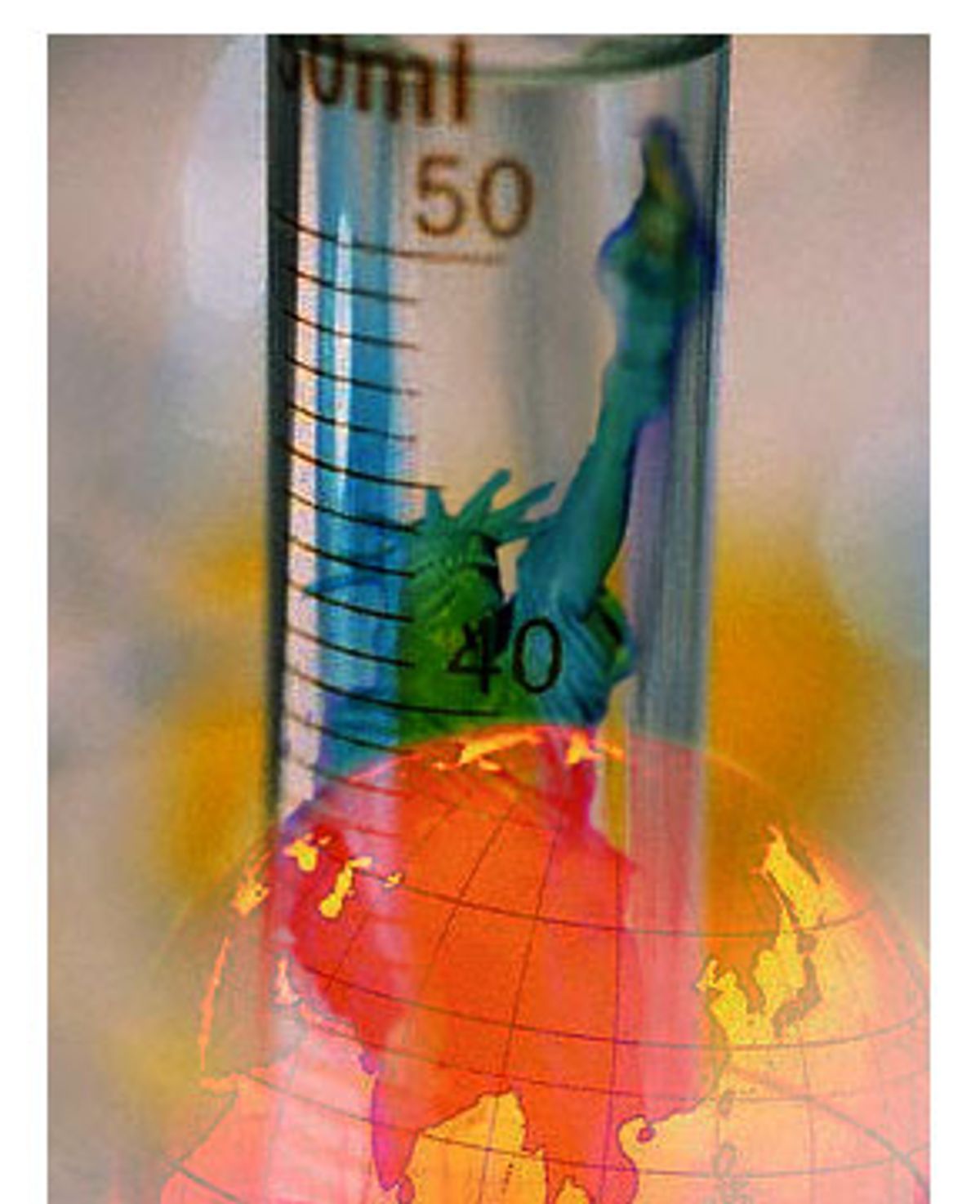

America's adventure in Iraq has produced, among other things, a new catchphrase: "exporting democracy." It's an odd term, with a crassly commercial timbre that rings hollow. How can we export something as intangible, as noble, as democracy? It's not the same as peddling bananas or microchips.

The real problem with the term, however, is that it is incomplete. It describes only half of the equation. The other half is the inescapable fact that we live in the era of globalization, where goods and capital flow across borders effortlessly, with the click of a mouse. So, logically, if the United States is now in the business of exporting democracy, shouldn't we be importing some as well? Isn't that what free trade is all about?

From now on, we need to think of democracy as an import-export business. It may sound blasphemous to some, but plenty of ideas out there are worth importing -- ideas about how to encourage voter turnout, hold leaders accountable, reach consensus, and more. True, these ideas weren't invented in the United States, but does that really matter? Smart companies, the kind that survive in difficult times, are always on the prowl for good ideas, no matter what their source. No less a red-blooded capitalist than Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric, says, "Good ideas are meant to be borrowed." If it's good enough for GE, I say, it's good enough for America.

Many Americans -- and certainly those in the Bush administration -- believe our brand of democracy is a finished product, the end of the line after 228 years of evolution. It's now a job for the marketing department. Yet when it comes to nearly every other area of our lives (with the significant exception of religion), we believe in unlimited horizons and infinite room for improvement. Nothing is ever finished. When IBM introduces its latest laptop, nobody declares the end of technology. Yet when it comes to questions of democracy, we blithely declare the end of history.

The problem stems from how we view the rest of the world. Foreign countries these days fit into one of two categories: threats in need of vanquishing or charity cases in need of rescuing. (Or, in the strange case of Iraq, both.) That leaves little room for us to learn from other countries' experiences. Why not view the world as a kind of laboratory of ideas -- ideas about how to, say, provide healthcare to all our citizens, or hold our elected leaders accountable, or encourage people to vote in the first place?

Roughly 100 countries can be labeled democracies, far more than just a quarter of a century ago. Some, such as Vladimir Putin's Russia, are illiberal democracies, Potemkin villages with all of the trappings and none of the substance of a real democracy. But surely among the rest there is something worth importing. Canada and Europe are obvious places to mine, but even India, that most improbable of democracies, can teach us a thing or two about the democratic arts. The Japanese could teach us the art of the apology. Corporate executives and government officials regularly take responsibility for their actions -- and the actions of those in their stead. When something goes wrong, they don't need to be coerced into resigning.

Here are some other democratic ideas worth importing, or at least worth considering. None are perfect, and I'm not suggesting that they should be imported wholesale. Hopefully, though, they can contribute to a much needed debate about what kind of democracy we want -- for Iraqis, yes, but also for ourselves.

1. Getting out the vote

The most basic measure of the vitality of a democracy is citizen participation: Do people exercise their right to vote? On this score, America's performance is abysmal -- and getting worse. In the last presidential election, only 51 percent of the voters cast a ballot, compared with 63 percent in 1960. (For midterm elections, the figures are even more dismal.) Virtually every other democracy in the world does better than us. The United States ranks 114th out of 140 in voter turnout since World War II, behind countries such as Uganda and Bangladesh and just barely ahead of Nigeria.

We could examine the myriad ways in which the United States has gone wrong -- or we can flip the question on its head and ask, What are other nations doing right? The answer is surprisingly simple. First of all, most nations make it much easier for their citizens to vote. Virtually no other country requires voters to register -- a process, it seems, designed to discourage people from voting. In most of the democratic world, when someone turns 18, he or she is automatically eligible to vote. And in most of the world, Election Day is either held on Sunday or declared a national holiday. People don't need to sneak away to polling booths during their lunch break. There is no reason the United States couldn't do the same. Such a simple change is bound to increase voter turnout by at least a few percentage points.

Other nations, such as Australia and Belgium, go a step further and make voting mandatory. Those who fail to cast their ballot are slapped with a small fine, about $20. It works. In those countries, voter turnout is not universal but it's awfully close -- about 85 to 90 percent.

Opponents of mandatory voting claim it is un-American, since in our country rights always trump responsibilities. Surely, the critics say, voting is a choice that each individual should make -- not the government. Yet there are plenty of aspects of our lives where the government compels us to act: getting a driver's license, for instance, or registering for the draft.

One reason that mandatory voting and other measures to improve voter turnout have floundered here is that they make politicians nervous. Republicans worry that more voters means more votes for the Democrats. "Experience around the world suggests that raising voter rates favors parties of the left," writes former Harvard president Derek Bok, in his book "The Trouble With Government." But, as Bok points out, even Democratic lawmakers resist reforms that might increase voter participation. "Politicians of every persuasion who have managed to get themselves elected under the current rules will worry about the effect of a large infusion of new and unpredictable voters," he says.

Of course, even if people could vote with the click of a mouse, many Americans probably wouldn't bother. They don't think their vote will make a difference, and they don't like their choice of candidates. Here, too, we don't need to reinvent the wheel. We need to import a new model.

2. Campaigns

It's a wonder the United States doesn't produce a higher caliber of politician. After all, no other country spends as much money -- or as much time -- electing its leaders. The U.S. presidential campaign lasts more than a year -- and members of Congress are perpetually in campaign mode. In Germany, campaigns last only 10 weeks; in Britain, they're even shorter, about 30 days. Voters in these countries do not feel short-changed. In fact, one can argue that the shorter campaigns focus voters' attention on the issues, while the marathon U.S. campaigns have a decidedly numbing effect. "People get fed up and after a while they just tune out," says Arthur Gunlicks, a professor at the University of Richmond in Virginia who has written extensively about the differences between American and European election campaigns. "If the campaigns were shorter, presumably people would be more willing to pay attention."

The United States is virtually the only country in the world that does not provide free television time to political parties or candidates. In countries such as Britain and Germany, the state provides each party with a block of TV slots, based on their relative strength in the Parliament. The slots are 5 to 10 minutes long, considerably longer than the 30-second blitzes of sound and fury that are U.S. political ads. Public financing of campaigns, the norm for most other democracies, means that candidates can focus on the issues instead of the money. Let's look at two fictitious politicians: Fred, a member of Congress from Denver, and Klaus, a member of the Bundestag, the German Parliament, from Munich. Fred spends much of his day attending fundraisers, meeting with representatives of political action committees, and plotting his fundraising strategy with staffers. In his spare time, he votes on legislation and meets constituents. Klaus, on the other hand, doesn't worry about fundraising. He does spend lots of time campaigning -- in fact, more than Fred -- but it is real campaigning, giving stump speeches and addressing the issues, not attending gala events, cup in hand.

No wonder campaign-finance reform is a uniquely American cause. For most democracies, it isn't an issue, because there is hardly anything in need of reform. Yet we Americans stubbornly cling to the belief that we couldn't possibly learn anything of value from other democracies.

3. Question time

To date, President Bush has held only 12 news conferences since taking office, far fewer than Bill Clinton or even George Herbert Walker Bush. Rarely does the public have a chance to hear George W. Bush unscripted. Not so for Bush's ally, Tony Blair. Every Wednesday at precisely noon, the British prime minister is peppered with questions from members of Parliament. The 30-minute sessions (aptly called Question Time) are raucous and unruly -- a kind of democracy reality show -- with M.P.'s hurling insults at the prime minister, who, in turn, hurls them back at the "right honorable gentleman." Question Time is partly political theater -- these days, what isn't? -- but the British public has a regular opportunity to see its leader respond to the most pressing questions of the day without a teleprompter or a handler to guide him. Many other countries, from Japan to Australia, also have some form of Question Time, and therefore a greater degree of accountability and transparency.

Is there any reason the United States couldn't adopt some version of Question Time? True, it would need to be adapted to our presidential style of government -- Americans don't like to see their presidents, even unpopular ones, publicly humiliated -- but as things stand now, the president need face Congress and the American public only once a year, during the State of the Union address. Any other appearances take place when the Karl Roves of the world deem it politically expedient. And Question Time has one other advantage: It is a lot more fun to watch than those scripted news conferences that have become a hallmark of the Bush presidency.

4. Direct democracy, Swiss-style

Switzerland places an unprecedented amount of faith in the wisdom of its people. What that means, in practical terms, is that the Swiss vote early and often. Every few weeks, the typical Swiss citizen casts a vote on questions ranging from whether to build a new bridge to whether Switzerland should join the United Nations. The Swiss constitution, is, quite literally, a document of the people; more than half of its provisions were born of referendums or ballot initiatives. Any Swiss citizen can bring a matter to a national vote by collecting 100,000 signatures.

Only about one in 10 referendums pass. But even the failures serve a function, since they give voice to people and causes that might otherwise never be heard. The process of referendums allows ordinary Swiss -- not only politicians -- to shape the national debate. For instance, some two decades ago a few Swiss wanted to abolish the army, and so they brought the issue to a vote. It didn't pass, but it did spark a debate about what kind of military role the Swiss want to play in the world.

Alfred Berkeley, former president of the NASDAQ stock market, says the Swiss political system "is the NASDAQ of democracies. It brings ideas to people faster -- and with fewer means of choking them off in transit -- than perhaps any other political system in the world." That system isn't perfect -- women weren't given the right to vote until 1971, and all those referendums slow down the wheels of democracy -- but surely elements of the Swiss system are ripe for import. "It is only by a perverse insularity, or a stubborn ignorance, that one would want to ignore the Swiss experience," concludes Gregory Fossedal in his excellent book, "Direct Democracy in Switzerland."

Would this kind of direct democracy work in the United States? Could we see U.S. voters deciding whether to ban gay marriage or whether to go to war in Iraq? Critics say no. American voters are too apathetic. They don't have the time, or the desire, to study these issues in depth. And besides, the naysayers claim, a few big spenders will hijack the process by "buying" the necessary signatures to hold a referendum, just as they did in California, the state that opponents of direct democracy like to point to as the example of what happens when voters go wild.

It's true that the Founding Fathers chose a representative form of government partly because they were wary of putting too much power in the hands of the masses. At the time, though, the masses were largely uneducated. Not so today. People have access to all the information they need to make informed decisions.

Fossedal argues that the Swiss system of direct democracy works so well because it is a system, not a bunch of random referendums, California-style. Swiss voters take their charge more seriously than Americans because "when someone knows he is going to be asked to render an opinion, and that opinion will become law, he treats the matter more seriously." The difference between answering a Gallup poll and voting on a referendum, he says, is the difference between a bystander to a murder trial and a juror. The latter is going to take the case much more seriously. There is no reason why American voters wouldn't also rise to the challenge.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I realize many Americans will balk at the suggestion that we should import democracy at all -- especially from tiny countries like Switzerland or impoverished ones like India. It's not that we're xenophobic. We love our reggae and our pad Thai and our Ichiro. Our embrace of foreign cultures, however, does not extend to the world of politics. When it comes to democratic institutions, if it's not Made in America, we don't want to hear about it.

But why? The answer lies in America's Myth of Creation, which goes something like this: One day, the Founding Fathers miraculously invented the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution out of thin air. There was nothing like it before and there has been nothing like it since.

The truth, of course, is that the Founding Fathers borrowed liberally from foreign thinkers -- Rousseau, Locke and Swift, among others (and, according to some scholars, from the Iroquois nation). Not only did our Founding Fathers borrow from foreigners; many of them were foreigners. These days, however, it is treasonous to suggest we have anything to learn from other nations, especially those cheese-eating surrender monkeys across the Atlantic.

Importing democracy does not mean importing foreign values or foreign cultures. Besides, much of what we import will be Americanized, just like California sushi. In this age of globalization, there is no such thing as purely American democracy or purely British democracy or, should it come to pass, purely Iraqi democracy. We are living in the age of mongrel democracy, where every nation consists of a hodgepodge of beliefs and institutions.

The greatest resistance to importing democracy is likely to come not from American citizens but from career politicians --- on both sides of the aisle. "You don't really know what's going to happen [if these ideas are imported], so there is a hesitation on the part of a variety of interests -- Democrat and Republican -- to take a risk," says Luis Fraga, a fellow at Harvard University's Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study. And what politician these days wants to be seen touting foreign ideas?

There are other, more strategic reasons why America should import, as well as export, democracy. It would improve our standing in the world and enhance what Harvard's Joseph Nye calls America's "soft power." Other nations would see evidence that all of this talk about globalization is not merely a smoke screen for Americanization.

Perhaps the best reason to import democracy, however, is a selfish one. It's good for America. This was something that the English statesman Edmund Burke recognized in the late 1780s, when he warned that "we must reform in order to preserve."

The Romans also knew this well. Their empire lasted more than 1,000 years -- longer than any other -- partly because they had a knack for brutality, no doubt, but also because they borrowed heavily from the peoples they conquered. The Romans, Jim Garrison writes in "American Empire," "appreciated Greek democracy and wisdom and absorbed them, along with the wise traditions of Egypt and Carthage."

So as we prepare to anoint another president, and as Democracy Inc. gears up for another bloody sales campaign in Iraq, I have one question for us to ponder. What wise traditions have we absorbed lately?

Shares