The first two-thirds or so of "Open Water" -- which runs a taut, economic 79 minutes total -- are so artful and effective that they might have heralded a new and significant niche for digital video. Because movies shot on film are so expensive to make, we live in a moviegoing era when there's virtually no such thing as a B-picture. Once in a while we get a movie that's satisfyingly "B" in mood and feeling (Guillermo del Toro's rousing, romantic "Hellboy," for example). But even the pictures we've learned to think of as cartoony, throwaway entertainment ("Spiderman 2" or Quentin Tarantino's two "Kill Bill" pictures), often not only cost millions of dollars but also seem to weigh billions of pounds. The high cost of making movies has led to a shortage of cheap raw energy. Movies these days run on expensive fossil fuels, not drugstore sugar jolts.

The unapologetically low-budget "Open Water" might have been different. Written, directed and edited by Chris Kentis, in collaboration with his wife, Laura Lau, "Open Water" uses real-life shark footage instead of special effects to spread its ominous caul of terror. For most of the picture, the camera lingers on the two central characters, Susan and Daniel (played, respectively, by Blanchard Ryan and Daniel Travis, who are a little stiff at first but eventually settle into pliant and believable rhythms), a hardworking couple who have finally gotten around to taking a tropical scuba-diving holiday. Susan and Daniel leave their island on a boat loaded with other scuba-diving tourists. Before long they've dropped below the surface to drink in the visual splendor of ocean life, crossing the paths of speckled, gaping fish who tootle along like undersea grandpas and patting the slithery flanks of velvety, mustard-colored eels.

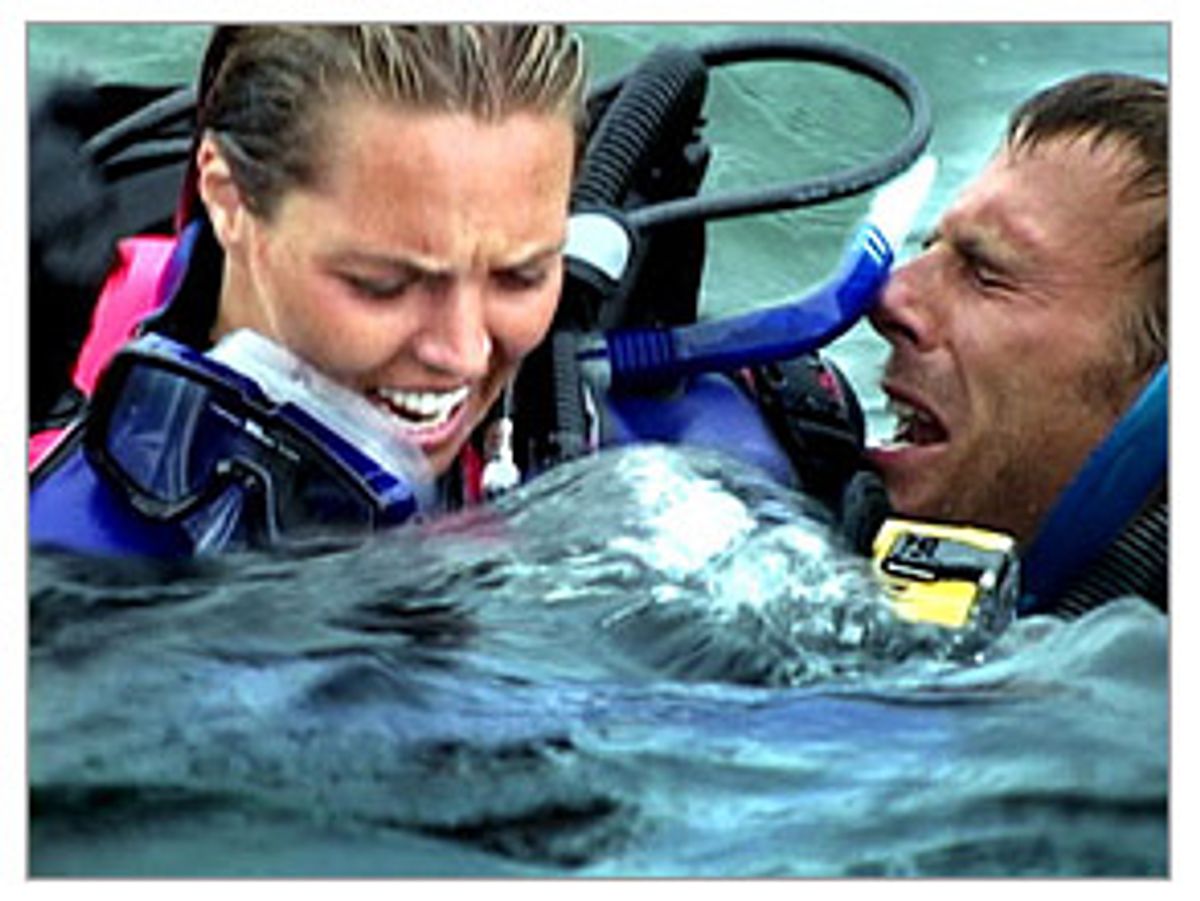

Even though Susan and Daniel take care not to spend more than the allotted time admiring these wonders of nature, the boat takes off without them, leaving them stranded far from shore. And that's when the real drama of the picture begins: This devoted but stressed-out couple become gently bobbing (and very cold) playthings of the sea, at risk of hypothermia and dehydration. But what really frightens them -- and us -- are the sharks who occasionally and without warning sweep past them, their pointed fins wiggle-waggling in a way that seems all the more unnerving for its appearance of playfulness.

Kentis and Lau (who collaborated on the shooting of the film; Kentis did all the in-the-water and underwater photography) use the shark footage sparingly and effectively, which is to say that the sharks don't actually do much. But the creatures' presence is both majestic and menacing, particularly in the movie's underwater shots. Their faces, with those wide, flat, hungry mouths, are unreadable: It's impossible to know what they want or what their intentions are. Kentis and Lau use these sharks, unapologetically, as one giant novelty -- they're like nature's version of William Castle's famous "Tingler" -- and for much of the film, the effect works. The picture offers a few "Jaws"-style bumps and scares that, in the best scare-movie tradition, make us laugh at our own jitteriness.

There are other moments in "Open Water" that ring with pleasurable, hammy obviousness: A local splits open a giant melon with a treacherous-looking knife (it whacks through the pulpy flesh with a mighty thud); various slippery or scaled critters bear witness to the sights around them, like a Greek chorus of indifferent gawkers. But Kentis and Lau didn't intend to make an enjoyably shivery B-movie: "Open Water" is ultimately a serious film about the unknowability and uncontrollability of nature -- and who needs that?

It's impossible to explain what's troubling about the ending of "Open Water" without revealing plot details, so any viewer who wants to remain surprised should stop reading now. That said, the ending of "Open Water" is hardly a surprise at all: What do you think is going to happen to two relatively helpless human beings left in the middle of the ocean for nearly 24 hours?

I'm sure some viewers will cheer the movie's grim, decidedly un-Hollywood ending (and they're sure to write letters accusing me of wanting to live in a Disneyfied world where bears talk and wear brightly colored pants -- although I assure you that I find talking bears in pants far more terrifying than sharks). Others will point out that the movie is based on real events (whatever that ever means). Regardless, my objections to "Open Water" shouldn't be taken as a plea for happy, plastic, unrealistic endings.

But when a director yanks the rug out from under an audience, leaving at least some viewers feeling hopeless and desolate after they've been invited to laugh at their own fears, we need to ask ourselves why we've been pulled through the wringer -- and if the experience was worth it. That answer will certainly vary from moviegoer to moviegoer. But "Open Water" is so smart in the way it asks us to identify with its main characters -- particularly in the way it maps the squiggly, overlapping psychological sine waves of two people who essentially care for each other, and who have found themselves trapped together in the direst circumstances -- that the ending, intentionally or otherwise, merely feels sadistic.

Killing off characters we've come to care about can be the hardest thing for a director to do -- or it can be the cheapest way to get a reaction out of us. Brian De Palma is one director who's often criticized of doing the latter. But De Palma, the great modern-day tragedian of movies, never kills off a major character without laying his own emotions bare first. No matter how distraught we may feel at Al Pacino's death in "Carlito's Way," or, even more significantly, Thuy Thu Le's in "Casualties of War," there's never any doubt that those deaths hurt De Palma as much as they do us.

Of course, "Open Water" isn't even pretending to be a Brian De Palma movie -- it begins, at least, as a faux-realist scarefest in the carny-barker tradition of "The Blair Witch Project." But while "Blair Witch" is defensible chiefly as a brash (and effective, if unpleasant) kids' stunt, "Open Water" almost achieves something bigger. Kentis and Lau succeed in doing what all filmmakers worth their salt strive to do: They make us care about their characters. Then they use them as a conveniently dramatic means to an end -- in essence, they throw them overboard in the service of some false notion of believability. We, the audience, shuffle out of the theater, feeling drained and punished. Those sharks were scary, and kind of fun: Shame on us for enjoying their creepy malevolence, but we've learned our lesson. Nature is cruel and unforgiving. And sometimes, movies are too.

Shares