Tuesday, Aug. 3

Forty-eight hours before the cease-fire collapsed in Najaf, the jovial al-Sadr militia sheik was sitting in the passenger seat of my car. We were driving down the long road toward Najaf, the Shiite holy city, from Baghdad, past Mahmudiya and Latayfiya, ambush towns hidden under long dark reefs of palm groves. In the back seat, I slept through the worst parts of the drive, waking up just north of the ruins of Babylon.

The sheik, a man who knew far more about me than I knew about him, did not dress in traditional Arab clothes. He did not, at least when he was around Westerners, wear the thin woolen abay, which is a symbol of rank and his right as a man of status. This barrel-chested man in his late 30s, a well-known figure of the Shiite resistance, was outgoing and intelligent. When he was in cellphone range of Baghdad, his phone rang every 20 seconds.

Perpetually hoarse from making arrangements, the sheik, perched in the passenger seat, was telling us what was going to happen. The sheik was fond of video above all other forms of mass communication because of its wide reach. He watched Al-Jazeera and Arabiya and knew that these stations catalyzed the Arab world against the American occupation of Iraq. Writers were not at the top of his list.

In a stroke of luck, Andrew Berends, an independent filmmaker from New York, had asked if he could ride with us to Najaf. The sheik took to Andy and his camera at first sight. For the next five days, we would travel together, recording the spreading violence.

As we headed south, the land flattened into white desert. Driving past a rime of houses along the highway, I realized that the man in the front seat was a new kind of Iraqi politician, half resistance fighter, half public relations man. He was worldly, not a cleric, and he lacked the soft manners of al-Sadr theologian-orators who had studied in Islamic seminaries. The sheik did not often speak of God, but he was careful to pray at the correct times. When he did, other men prayed behind him.

The sheik had an unsettling talent for finding out a great deal about new acquaintances. If the sheik wanted to know something about you, he asked everyone who knew you for information and was not satisfied until he got what he was after. The sheik did not mind if the background check made you uncomfortable, and it was unwise to lie to him. I never saw him look tired.

South of Latayfiya, we passed a convoy of Humvees and the sheik laughed when he saw the American soldiers. "Look at them, they are begging for rockets," he said. As it turned out, the rockets were on their way. The cease-fire was about to collapse.

In fact, the critical event had come on Monday, the day before we left for Najaf. U.S. Humvees and Iraqi forces had fired on buildings near Muqtada al-Sadr's house and attacked al-Mahdi army fighters across the street. According to witnesses, U.S. and Iraqi forces had come down the street several times before, but this would be the last straw and a deliberate provocation.

To show how dangerous the situation would become, the sheik, while in his Baghdad office, had given me a copy of a letter. It was a general mobilization order for all Mahdi forces in Iraq and had come directly from Muqtada al-Sadr's office in Najaf. Dated Aug. 2, the letter said that Americans had broken the terms of cease-fire and the militia would immediately go on alert -- a credible sign that things were about to go up in flames. As we drove into the center of Najaf, I kept the al-Mahdi mobilization order in my pocket, tucked under a safe-passage letter that was long out of date.

Our first stop in Najaf was at Muqtada al-Sadr's house for a look at the firefight damage. The sheik wanted us to see it. Set in the middle of an unremarkable block, with a view of a parking lot, Muqtada al-Sadr's house didn't look like much -- it was an exercise in modesty. Smaller than the houses around it, it was a simple two-story Iraqi modern place with aluminum gates and high walls. There was nothing to distinguish it from the neighbors except the cell of well-armed fighters across the street and the burned-out shell of a car on the sidewalk.

When we got out of our car to take a look around, the sheik ran over to the Mahdi guards to explain what we were doing and to get the latest news. The sheik joked with the house guards, who were happy to see him, and in a few minutes they took us on a damage tour. Without the sheik, we would have been arrested on the spot.

I asked a young guard near the house if he had seen the firefight; he said he had. He then gave us a detailed account that Andy recorded.

"The Americans are coming to provoke us and came four times but our people had no permission to fire," he said. "They crashed through checkpoint barriers. The fourth time was yesterday. A woman died and a hospital was damaged. God will punish them."

One U.S. news story said the patrol that went by Sadr's house had become lost in the city, ending up there by mistake. Since a new unit was patrolling Najaf, this was a possibility. But I believed, as other observers did, that the U.S. provoked the Mahdi army into all-out war.

Najaf, a desert city at the edge of a flood plain, with its great gold dome of the shrine rising over the necropolis, was filled with pilgrims and everyone else. The city was devoted to its sacred dead. During the hot hours of the afternoon, the city emptied, but at around 6, residents woke up from their siestas and opened their shops. The city was busy and the sheik seemed to know it well.

After leaving Muqtada's house, Andy and I followed the sheik to evening prayers at the shrine. We walked up Rasul Street, a busy street where I have many friends. At the mosque was the usual spectacle of families carrying their dead along a circuit through the shrine gates before burying them in sacred ground, shouting, "Allah, Allah, il Allah." Andy filmed the hundreds of praying Sadr supporters, holding his camera close to the face of the imam, Jabbar al Khafaji. The sheik kept us from being thrown out.

Later that evening in the mosque, I spoke to the sheik Ali Smeisem, a senior advisor to Muqtada, about the precarious nature of the cease-fire. I asked if the truce was going to collapse. "The violations were completely against the accepted peace plan," Ali Smeisem said. In his late 50s, he spoke with a serious and measured style common among diplomats. "We gave instructions to the al-Mahdi army not to target American forces, but they shot the guards of the house. We are peace seekers."

In retaliation for the attacks against Muqtada's house, the Mahdi army kidnapped Iraqi police officers. It seemed the militia was trying to preserve a balance, avoid all-out warfare, yet still respond to the attacks at al-Sadr's house.

When I asked Smeisem if the Mahdi army would participate in the Iraqi elections scheduled in January, he said yes, it would. I was surprised. They were getting ready to field candidates in national elections. The U.S. would certainly find an electoral victory for the Mahdi difficult to live with in post-Saddam Iraq. If one accepted that logic, the drive to crush Muqtada would have to begin before the U.S. elections in November and Iraqi elections in January.

I knew the war was going to start again, but I didn't stay in Najaf. The mobilization order, police kidnappings, bellicose statements of the new Iraqi prime minister, Ayad Allawi, all pointed to renewed fighting. At the time, though, I thought it was important to return to Baghdad. Besides, the sheik wanted to be dropped off in Sadr City, and he wanted to leave immediately.

That night, after leaving Smeisem at the shrine, we found a pilgrim hotel and slept fitfully.

Wednesday, Aug. 4

In the early morning, we left for Baghdad. Our car broke down south of Latayfiya, one of the ambush towns, so we caught a minibus into Baghdad. The fighting would start in less than 24 hours.

Thursday, Aug. 5

The manic acceleration started. From here on out, each day would be worse than the previous day, less predictable, all guarantees of safety steadily eroded.

Andy and I were coming back from the Associated Press office when we heard that U.S. and al-Mahdi forces were fighting in Najaf, that the battles were fierce, were not skirmishes, and the U.S. was claiming hundreds of fighters killed. We quickly called the sheik in Sadr City and asked permission to meet him in his own sector. Sadr City always follows Najaf in violence and we wanted to make sure we would be allowed through the checkpoints. The Sadr sheik agreed to let us come. We didn't stop at our hotel; we went straight to Sadr City. Without his permission, the door to the Shiite district would have been locked, but he wanted journalists to document the resistance, and he wanted the resistance to be on television.

We arrived in the afternoon to find Sadr City sealed by al-Mahdi checkpoints. Hundreds of fighters in black were guarding the major intersections with rocket launchers, rifles and mortars. At the intersection closest to the sheik's house, we stood in the sun watching the fighters wire artillery shells as roadside bombs, then cover the devices with bits of scrap metal.

The sheik directed traffic and posed for photographs. An Iraqi fighter with his face covered said, "We are going to fuck them. We are going to destroy them. The Americans violated the truce." When I asked him his name, he said it was "Muqtada."

Battles between U.S. and Sadr forces erupted later in the day, just as the Mahdi army was kicking us out of town. According to one story, another militia official had seen us and had become irritated with the media presence. Across the rooftops, we watched a cloud of smoke and dust rise from an air strike, but our guides would not allow us to stop. At least 26 people were killed in Sadr City on Thursday, bloodier than some of the worst days in Najaf.

Friday, Aug. 6

On the second day of fighting, Andy and I decided to stay away from Sadr prayers at the mosque and remain in Baghdad. We drove to Sadr City in the early evening, hoping to see what happened at night. I had never been allowed to watch the fighters work at night and the sheik was offering us a degree of access that very few journalists have had in Iraq.

In a kebab restaurant across from his office, the sheik offered to take us to an attack site. We immediately agreed. We took a short drive down a broad street until we heard car tires squealing as drivers in front of us caught sight of an American Bradley convoy and made panicked U-turns. Then we made a quick left down a nearby alley. The Bradley convoy parked across the street.

Light was almost gone and it was settling down into dusk. We got out of the car with the sheik and saw a pickup truck with five Mahdi army soldiers speeding down the street toward us. The fighters jumped out and one man ran down the street with a rocket launcher, telling Andy not to film him. He then knelt down and fired a rocket-propelled grenade at the Bradleys from the corner where the alley met the broad avenue. We had just ducked inside a door of a house when the fighter pulled the trigger. The blast was deafening and the rocket missed the convoy.

A few minutes later, a firefight broke out and the Bradleys returned fire with their machine guns; the air sounded like it was coming apart along the seams. Some local people took us in, and an old patriarch, a descendant of the prophet, told us that Americans, "Instead of showing us respect for human rights, they violated them. Instead of preserving the riches of the country, they wasted them." The family was warm. They sang Muqtada songs. We drank tea with them and then walked outside into the warm night air.

We left Sadr City in the dark and saw fighters pouring gasoline on the tarmac, lighting it, then burying roadside bombs under the soft tar. By morning, the city would be a minefield with hundreds of explosives hidden beneath the roads. At night, the burning tarmac made the place look infernal, the orange light of the fires guttering below a blank sky without stars.

Saturday, Aug. 7

In the lobby of our hotel in Baghdad, we hired a new driver named Ahmed. It turned out to be a stroke of bad luck because he would cause problems. And any problem is a serious problem. He was lazy and dishonest, although we didn't know it yet. We also didn't realize that he was setting himself up as a fixer and guide to urban warfare in Sadr City, who didn't want competition from any of our contacts.

Ahmed took us to Sadr City but did not bring us to the sheik, the man who made it possible for us to stay in town, the man we had arranged to meet. Instead, Ahmed made his own deal with fighters in a different sector. We spent an hour at an ambush position a few blocks over from some very heavy fighting with Americans, waiting for a battle that never took place. We waited for an hour, talking to the commanders, promising not to show the identities of the fighters on the tape.

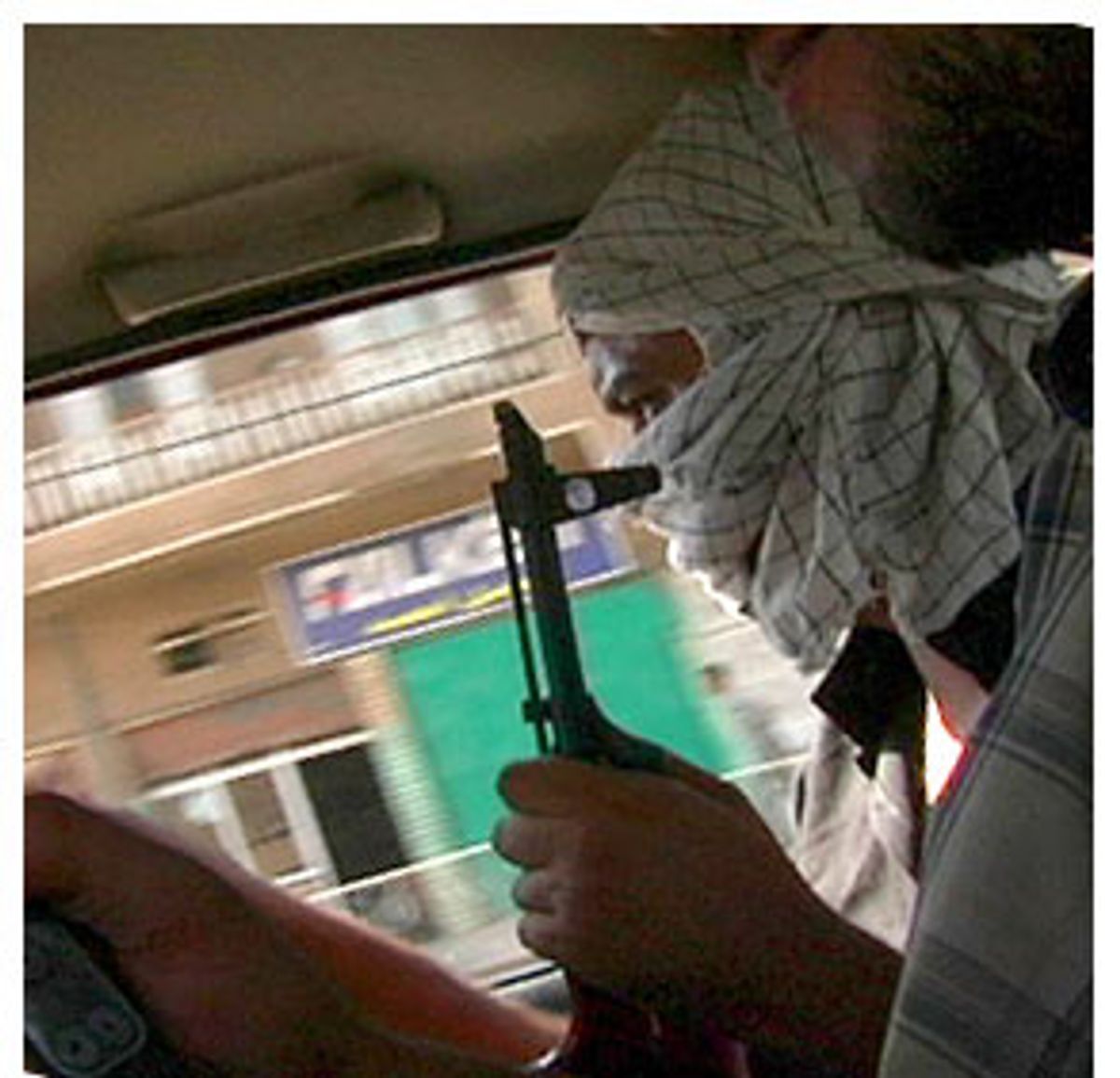

After a tense wait with sporadic gunfire breaking out down the street, the commander of the sector told us to follow a group of his fighters in our car. They piled into a white sedan and we followed, listening for helicopters overhead. We were told not to take photographs of their faces and waited while they wound scarves around their heads or pulled down ski masks.

We didn't know what would happen next, but small groups of fighters were leaving their sector to attack the Americans a few blocks away. We followed their car for a few blocks and then parked. A young fighter with a bandaged hand and a sniper rifle got out, ran to a corner, knelt, then fired four shots at some American vehicles. Andy filmed the sniper taking aim and pulling the trigger. After he fired, the sniper said, "It's OK, it's OK," running back to his car. We followed. Back at the intersection the sniper was waving his gun out the window in triumph and the men who saw him cheered.

We decided to wait for the sheik to come for us because we couldn't move freely with battles going on a few blocks down Falah Street. We called our man every five minutes. When he found us in the new sector, our driver made the error of threatening him; he didn't know who the sheik was. Our Mahdi army protector then left us at the intersection, furious, and he would not forgive the lapse of honor.

Minutes later, the Mahdi army fighters on the corner kicked us out of the city, escorting us to the border with Baghdad, saying the order had come down from the Sadr office, which wasn't true. When I got back to the meeting point just outside town, we learned that a colleague and a close friend also working in Sadr City that day were abducted and beaten by a carload of armed men. It was a miserable day. The photographer who was beaten by the gunmen was a brave journalist and I couldn't stop thinking about him in his torn shirt, his face swollen from blows.

Back in our Baghdad hotel, I heard the sounds of mortars landing in the Karrada district. The Mahdi army was firing mortars in retaliation for the fighting in Najaf. This was a new tactic, sowing chaos in Baghdad to protest the American assault. The Mahdi army would also threaten the oil pipelines and successfully stop the flow of oil to Basra for a few days. A fighter with the Mahdi army told us that there were Western targets outside Sadr City that the militia planned to attack. He named rocket attacks on ministries, firefights in rich neighborhoods. Much of what the Mahdi fighter told us turned out to be true.

Sunday, Aug. 8

As we drove to Sadr City, Andy took deep breaths. He hated the ride in. "Once I'm there, I'm fine," he said. It's true, he was fine once he was in. I also hated the ride in, but I didn't have a ritual beyond waiting for the fighters at the checkpoints to order us out of the car and ask us for the safe-passage letter. But that didn't happen today. We arrived in Sadr City at around 9:30 in the morning. As we drove through the furnace air and the nearly empty streets, heading for the sheik's house, Iraqi fighters in Geyara shot down an American helicopter with an antiaircraft missile. It happened quite close to where we were driving, in front of the al-Quds mosque. On our way to the mosque, we could see Apaches flying cover. One fired down into the houses near the helicopter crash site. We saw the white flashes of the cannons as they were fired. We drove closer to the crash site and parked. As soon as the car stopped moving, Andy took his video camera and ran toward the mosque, disappearing inside the battle.

After a short lull, a convoy of Bradleys surrounded the mosque and al-Mahdi fighters started to converge on the scene, cutting Andy off from us. When I called Andy, a fighter answered his phone, but that wasn't the real problem. Fighters often take cellphones from journalists as a security measure and then give them back when the operation is finished. The real problem was the fighting was just getting started and there was no way to move.

On the opposite block, I watched Apaches come in fast and low, looking for targets, while Bradleys fired at militiamen converging on the crash site. The downing of the helicopter was the beginning, not the end, of battle. Fighters carrying rocket launchers sprinted down our alley in groups of four and five. During one of the helicopter passes, the pilot brought his Black Hawk so low that I could see the bootlaces of one of the gunners. When the machine turned to face the crowd of Iraqis on the corner near the mosque, I felt ill. There was the black shape of the machine and a shuddering sound from the rotors. It did not fire at us.

While I was trying to contact Andy, I was swarmed by kids who wanted to know where I lived. They told me their names in between approaches of the U.S. helicopters. They showed me how they made Molotov cocktails for their older brothers and fathers to throw at American vehicles. One young boy, more outgoing than the others, asked me to name the great Shiite imams in chronological order. After I gave him the first four, we were friends.

Soon, I was sitting in a nearby house with a family, drinking cold water. The women were terrified; but inside the walls of the house, the hospitality of the patriarch reigned. Inside, there were only old men and young boys, as all the fighting-age men were outside with weapons. The family that took me in had nothing, not even clean water or electricity. But everything they had, they offered their guest.

From the house, I made a series of calls to the sheik to tell him Andy's situation and asked him to come to the al-Quds mosque to help get him out. The sheik said he would come. I waited.

Andy, unable to move through the battle near the mosque and the crashed helicopter, was taken in by an Iraqi man and given shelter, while Bradleys sealed off the street and fired at the Mahdi fighters. After a few rough hours, Andy reappeared with the sheik, who had somehow managed to find him in the blocks near the mosque. We drove around the sector and stumbled upon U.S. recovery crews, dragging the shattered carcass of the helicopter down the road. The sheik was overjoyed when Andy filmed it. Clusters of Iraqis watched the recovery crews from the street corners, hiding from the Americans and laughing.

As I write this evening, news that U.S. Marines are fighting in the center of Najaf is just coming over the wires. Muqtada's block has been bombed, and a great torrent of smoke is boiling out of the old city. In Sadr City, where the Mahdi army has almost universal support among the 2 million people who live there, the fighting is not coming to an end. It is just beginning.

Shares