It is a very hot summer in Palestine. In Ramallah, the city in the West Bank where I live, this summer has been hotter than any I can remember. In Gaza, further south and on the coast, it is roastingly hot and humid as well.

Gaza has been exploding, but I have not been there for six months. The Israeli authorities have denied me a permit to travel there. At least they gave me a permit to travel within the West Bank, which many Palestinians can't get. Even to travel within the West Bank, which is supposedly under Palestinian control, you now need to apply to the Israelis for a special permit called an "internal checkpoint permit." A few years ago, Palestinians needed a permit only to go to Israel -- and there was a security corridor between the West Bank and Gaza that allowed Palestinians to travel in their own territory. This corridor has been closed. Now we need permits to travel within our own territory. There are checkpoints everywhere. This is one of the main reasons that life in all parts of Palestine, not just Gaza but the West Bank as well, has become increasingly intolerable.

My wife, Benaz, who is also a journalist, has not been to Gaza since the end of September 2000, when the current intifada erupted. I really feel sorry for her, because her family is there. She has not seen her mother for four years. My daughter Tamar, who is 8 years old, has not physically seen her grandmother for four years. However, thanks to the Internet, she is able to communicate with her via a webcam.

I admit, though, that I have mixed feelings about the fact that my wife and daughter aren't allowed to visit their family. When you're in Gaza, you never know when and where the next Israeli missile will strike. Israeli attacks have killed many civilians there.

But it isn't just Israeli missiles that one has to fear in Gaza now. The Strip, one of the poorest and most densely populated places on earth, in effect a vast prison camp, descended into chaos last month after Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat appointed a relative to a top security post there. Palestinian militants and security forces jockeying for control abducted several officials (including the police chief) and foreigners and took over government buildings. Rival security forces even exchanged gunfire. My Gaza colleagues tell me that many journalists were threatened when they took pictures of the events. They also tell me that armed men are swarming through the streets. They are not members of the Palestinian Authority security forces but of militias, mainly Fatah, the principal component of Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization, or PLO.

The anarchy in Gaza has roiled the shaky Palestinian government, such as it is. Prime Minister Ahmad Qurei'a resigned to protest his lack of power, then withdrew his resignation after Arafat promised to grant him more control over security forces and to implement reforms. Whether Arafat will follow through on these promises is, to put it politely, uncertain.

The crisis is far from resolved, and it has led to some of the harshest criticism Arafat has ever received from his own people. As Palestinians' lives have become increasingly hellish, they are less and less willing to put up with a leadership many regard as confused, corrupt, unwilling to rein in militant factions, and useless in achieving anything real for its people.

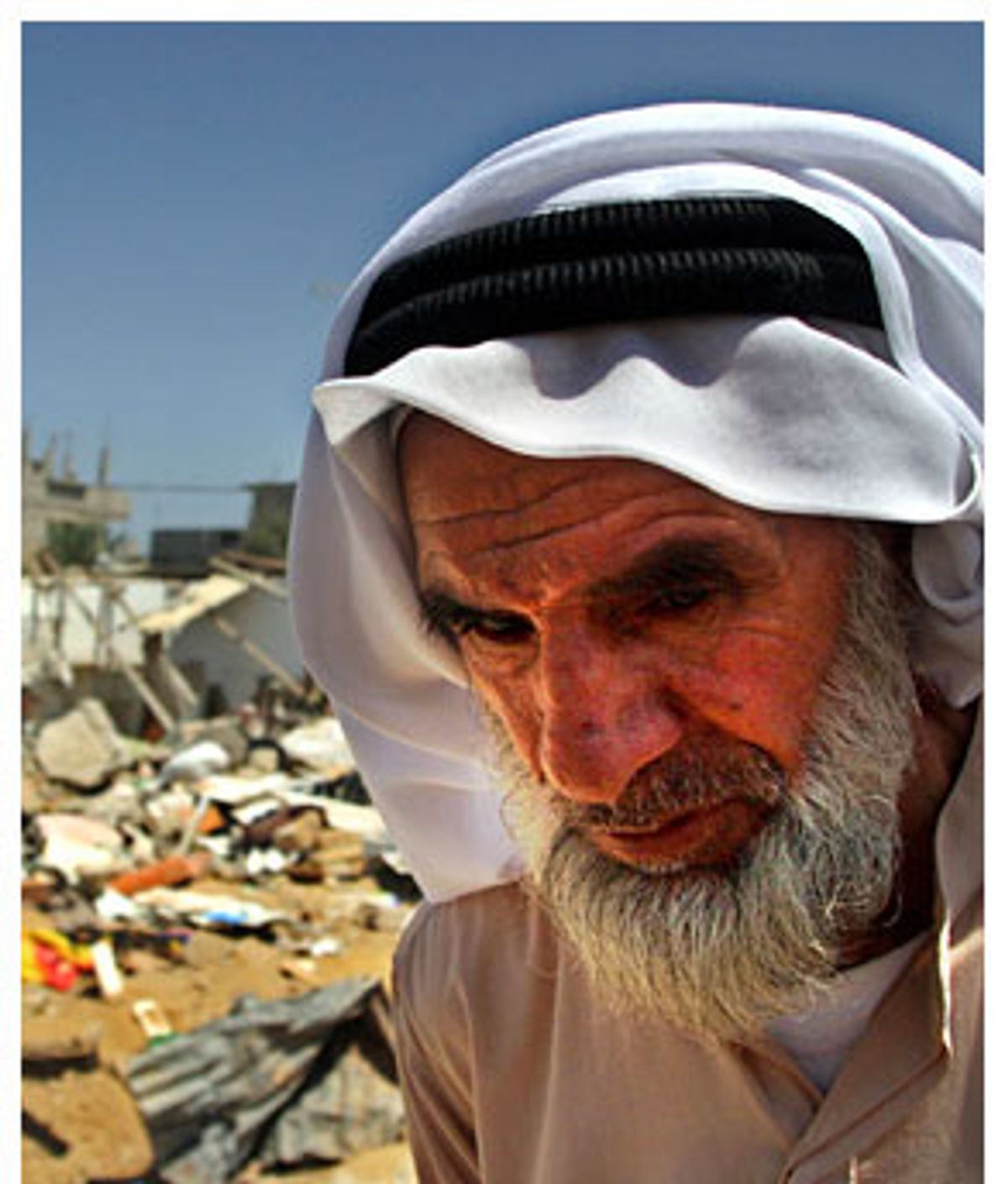

A remarkably frank new report on the chaos in the Palestinian Authority, based on an investigation by the Palestinian Legislative Council, explicitly blames Arafat for the breakdown, saying that he failed to define the mission of the security forces and to control them. The report, by a five-member panel that included both reformers and Arafat loyalists, calls for Qurei'a to resign and for an end to Qassam rocket attacks from the Strip into Israel. The rocket attacks led to savage Israeli military reprisals, including many house demolitions, killings, and an infamous attack on a peaceful demonstration in the city of Rafah that killed a number of civilians.

Many Palestinians think Mohammad Dahlan, the former national security advisor and the former chief of preventive security, initiated the Gaza events as part of a struggle for power with Arafat. Dahlan, who has called for reform in the Palestinian leadership and is the Americans' and Israelis' favorite choice to replace the aging Arafat, denies that he was behind the upheaval in Gaza. But his credibility is being questioned by many Palestinians. One university student told me, "Dahlan is no less corrupt [than the Palestinian leaders he has criticized]. When he came back from deportation, he came with only one shirt. Now he owns two villas in Gaza and has a convoy of fancy armored cars. People who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones."

Dahlan, once one of Yasser Arafat's most loyal followers, has become one of his harshest critics. In an interview with the Kuwaiti daily newspaper Al-Wattan, Dahlan criticized Arafat for not carrying out promised reforms and threatened that if these reforms "are not carried out by August 10, huge protests, which are expected to include 30,000 Palestinians, will take place in the Gaza Strip." Aug. 10 passed and no one took to the streets. News came from Arafat's headquarters about a phone conversation between Dahlan and Arafat during which Dahlan denied that he had planned the massive demonstration. In fact, no one knows what the two men talked about.

Dahlan used corruption and nepotism in the Palestinian Authority as a pretext to make his move. But he timed it badly: Gaza boiled over at the worst possible time, just when the International Court of Justice in the Hague ruled that the wall the Israelis are building around cities and villages in the West Bank was illegal because it constitutes a de facto annexation of Palestinian land. (To protect Israeli settlements, the wall carves out vast stretches of land outside the "Green Line," Israel's internationally recognized pre-1967 borders.) A subsequent U.N. resolution condemning Israel passed almost unanimously, with the entire European Union voting against Israel. The chaos in Gaza distracted international public opinion from one of Israel's most serious diplomatic defeats in decades. Arafat and his supporters, for their part, used this fact to attack the reformers. The Palestinian people themselves have little faith in either side, regarding the reformers who abducted the police chief as no less corrupt and nepotistic than Arafat's cronies.

In the Arab world, there is always a conspiracy behind everything, and this is certainly true of Palestinians. Clinging to the myth of national unity, they see anyone who upsets that myth as a traitor and collaborator by definition. And so when militants took to the streets in Gaza just when the U.N. General Assembly met to discuss the Hague ruling, many people said that the Israelis and the United States were behind it. This claim is dubious, since many of the militants are known to be from the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, but it was widely believed anyway.

The situation is not quite so dire in the West Bank, but here too unrest has escalated to violence. Members of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, a group linked to Arafat, attacked the governor's office in Jenin on July 31 and set fire to the military intelligence office, explaining that they did so because "no one was listening" to their demands. In Nablus the following day, members of the pro-Arafat Al-Awda Brigades showed up at a building where dozens of Fatah members who were demanding reforms were about to meet. The conference was disrupted when Brigades gunmen started shooting in the air. Fortunately, none of the participants was injured.

Many, especially Israelis and foreigners, thought that the deteriorating situation in the Gaza Strip would eventually put an end to Arafat's leadership. Certainly the open criticism Arafat has recently received would seem to support that notion. But in fact I believe the opposite is true.

Ali Jarbawi, a professor of political science at the West Bank's leading educational institution, Bir Zeit University, says "Arafat is stronger than ever and holds all the strings in his hand." Jarbawi has penetrating insights into a wide range of issues: I frequently go to see him when I'm confused about where Palestinians stand. "All those who want Arafat removed know very well that they cannot do it, because in Fatah there is nothing systematic and coherent, and this is what strengthens Arafat," Jarbawi says. "It is very hard for a well-organized institution to win over a fragmented institution -- Fatah is fragmented. The stronger is always the fragmented system. Arafat is a master of this disorganization. He is a well-organized controller of a disorganized chart."

Given the weakness of the Palestinian Authority, many Palestinians -- some secular, others who disagree with Hamas' violent tactics -- fear that the militant Islamic group will take advantage of the situation and seize power. However, Hamas leaders are shrewd enough to stay out of the internal conflict. Hamas leader Khaled Mashal, in an interview with Islam Online, stressed that Hamas is not siding with any party in this conflict. The Gaza events "should be dealt with as an internal dispute within the Fatah Movement and the Palestinian Authority," he noted.

Mashal called for comprehensive political and financial reform and an end to "one-sided political decision-making."

So with Arafat firmly in control of his chaotic organization, with the Israelis and their American backers continuing, in defiance of the Hague and the rest of the world, to build the wall, what are ordinary Palestinians thinking? What do we want?

Above all, we want honest and intelligent leadership. We're tired of the one-man show. We want strong leaders, not those who say one thing in English and the opposite in Arabic. Many Palestinians in public and among themselves (not to the media) believe that Arafat is doing nothing for the Palestinians and demand that reform be a Palestinian priority and not an Israeli or U.S. demand. We want a clear political strategy to end our endless conflict with Israel. We want to have a leadership that is able to communicate to the people what its vision is, one that reflects the needs of Palestinians. Those are real needs. Fifty-six percent of our people live below the poverty line; people are suffering from malnutrition. We want to fight corruption: We all know of people who are corrupt, or appointed out of nepotism, but nothing has been done. We want the security system completely overhauled. There are men with guns everywhere, and this must stop. It endangers Palestinians.

How can these changes be made? Elections are the obvious answer. But Arafat isn't rushing to hold them. And in any case, no elections can take place when the Israelis can at any minute storm into towns and villages and arrest people.

Nor is it easy to speak out against the existing leadership. Although most Palestinians believe that Arafat is an obstacle to reform, few people dare to say so publicly. Nothing and nobody stands up for freedom of speech in Palestine. Rather Palestinians prefer to blame the Israelis for all of their problems. And Arafat is still the symbol, the embodiment, of the Palestinian revolution. Thus hundreds of his supporters marched to the half-ruined Muqata, where he has been confined by the Israelis for almost three years. Standing in the front yard on the rubble of the 60-year-old military compound built by the British, the crowd chanted, "With our souls and blood we sacrifice for Arafat." He interrupted them, as usual, saying "No, with our souls and blood we sacrifice for Palestine." He then told the crowd, "We will overcome all conspiracies."

All of this Palestinian unrest followed Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's disengagement plan, which he is trying to push unilaterally through -- over the objections of his own Likud Party and without any agreement with the Palestinians. The struggle in Gaza is all about who will take over when and if the Israelis pull out.

When Sharon proposed his plan, he counted on Gaza imploding. Gaza means nothing for the Israelis; it has no religious or ideological significance. They are paying millions of dollars to protect the handful of settlers who are there. Why not leave and give the Palestinians a shaky "state" there? Then Sharon can say: "I gave the Palestinians a generous offer, I gave them a state in Gaza, I am the only Israeli P.M. who gave the Palestinians a state" -- just like Bush, who masks his total tilt toward Sharon by saying, "I am the only U.S. president who has called for a Palestinian state."

Sharon's intention is not to drive Gazans out: He want to isolate them in their own miserable "state." But he does want to drive Palestinians out of the West Bank. The West Bank is vital to him: It is home to almost all the settlements; it overlooks Tel Aviv and the heart of Israel.

Whatever Sharon's intentions are, and Palestinians have no illusions that they are good ones, Palestinians welcome any Israeli withdrawal from any of their territory. The critical difference between the Israeli position and the Palestinian one is simple: Palestinians want the Gaza withdrawal to be accompanied by a wider withdrawal from the West Bank and to be part of the "road map" for peace.

But many Palestinians doubt that Sharon plans to withdraw at all. Dr. Mustafa Barghouthi, the secretary general of the Palestinian National Initiative, says the disengagement plan "is a plan to turn the Gaza Strip into one big prison," because "in reality what is taking place in Gaza is not a withdrawal, not even a preliminary one. It is a gradual reoccupation, similar to what Israel has done in the West Bank, a methodical destruction of Palestinian institutions and an Israeli attempt to turn the Gaza Strip into a large 'prison' surrounded by Israeli presence on all sides."

Gaza is already a large prison, one where about 2 million Palestinians live in desperate economic, health and security conditions, a dire situation made even more intolerable by internal conflict and Israeli military operations.

And now, thanks to the wall, the West Bank is also turning into a big prison. As the wall surrounds villages and cities, each is becoming its own jail.

The wall is expected to be 750 km (460 miles) long, with a buffer zone of three to 40 meters (9 to 130 feet). The problem Palestinians have with the wall is not that it protects Israel's security, but that it is built inside Palestinian territories. Palestinians and Israelis can't even agree on what to call the barrier. While Israel calls it the "security fence" or "separation fence," Palestinians call it the "apartheid wall." Whatever it is called, the truth is that it will even further maim Palestinian life in the occupied territories.

Khalil Tufakji, a Palestinian geographer and expert in Israeli settlement affairs, told me that in the West Bank the wall "will preserve approximately 94 percent of the Israeli settler population, while approximately 60 percent of the settlements will also remain. While these settlers will be able to travel freely in the occupied territories, the wall will deny thousands of Palestinians the ability to move."

In the large, open-air prison that is being built, Palestinians will have to get special permits from the Israeli authorities to be able to move from one part of a city or village to another. According to B'Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, "Since October 2003, Israel has implemented a new permit system in the enclaves it created between the separation barrier and the Green Line. As a result, Palestinians without a permit are denied the right to work their lands to the west of the barrier."

My cousin, who lives in Qalqilia, in the northern West Bank, with her husband and three children, tells me that the city is surrounded by the wall, and that the only exit from the city is an iron gate manned by Israeli soldiers. The other day, when she visited us here in Ramallah, she told me that it feels like being freed from prison.

The Israeli peace group Gush Shalom reports that in the Qalqilia area "the wall is expected to have a devastating impact on the lives of some 210,000 Palestinians, living in 67 towns or villages." Their records show that "11,700 people in 13 villages will be imprisoned between the wall and the Green Line."

The holy city of Jerusalem, vital to three faiths, is also becoming a prison. The Israelis have started building the wall there: I can see it from the window of my office in Ramallah. Many of my friends who live in East Jerusalem neighborhoods north of the city, closer to Ramallah, will be enclosed by the wall. This means that I will not be able to see them as often as I do now, because I can't go to Jerusalem, the city where I was born 35 years ago. The Israelis consider Jerusalem to be part of Israel, and therefore West Bankers are allowed into the city only with a special permit. I applied for it but am still waiting for their approval.

Once the wall is completed, Jerusalemites in the outside-the-wall areas will have to go through Israeli checkpoints guarded by soldiers to get in and out of the walled-in area. This is all done in the name of security.

A few weeks ago, Israeli peace activist Uri Avnery told a group of Palestinian and Israeli protesters: "This wall has nothing to do with security; it does not separate between Israelis and Palestinians; it separates, as anybody can see, Palestinians from Palestinians in order to make their lives miserable."

It is hard for those who have not experienced checkpoints to understand the effect they have on your life. At a checkpoint you wait in line, in sun or rain, with Israeli soldiers checking every individual. The checkpoints can be maddeningly slow, or abruptly closed. Students can't get to their universities. Sick people have to wait at checkpoints. Many women have delivered their babies at checkpoints.

A friend of mine, who lives in Ramallah and whose two daughters go to a school outside Ramallah on the way to Jerusalem, tells me that there were times when his daughters did not make it to school or were delayed coming back. Once he says that the Israelis soldiers opened their school bags and searched it with their guns. They even used their gun to search a sandwich bag, which so disgusted his daughter she threw the sandwich away.

Of course, this has an effect on the children. I interviewed some children who were crossing at the Qalandia checkpoint. Eleven-year old Safwat Saqer said, "Sometimes I am late to school. I get angry at the soldiers because they turn back sick people who are going to the hospital and sometimes they do the same to us children. I wish I had a gun so I could attack them all. Kill them, not leave any of them alive."

I feel terrible that a child, who should be enjoying his childhood, says such things, thinks such things.

The fact is, a political solution to this nightmare is within reach. At Camp David and then at Taba, the two sides got close to agreement, and they could again. In fact, many Palestinians now would accept less than the Taba proposal: They simply want a normal life. Palestinians still want the contentious issues of Jerusalem and the plight of the refugees resolved fairly, but they want to see smaller changes: removal of checkpoints, a better economic life. At Camp David the demand was Israel's return to the 1967 border; now we demand the removal of the wall and to be able to cross to Jerusalem.

I was born in Jerusalem and although I live only a few miles away, I am not allowed into the city where I was born. How many places in the world can this be this true?

Nothing is normal here. And with all the hatred that has built over the past three years, it's hard to imagine when the two peoples will be able to think about reconciliation. Both sides have suffered greatly, and it will be a long time before either of us can overcome that. We feel that the Israeli people are not helping and that the Israeli government does not want peace. The Israeli peace camp is doing very little. Even those Palestinians and Israelis who still believe in peaceful coexistence feel that their hands are tied by the actions of the Israeli soldiers in the occupied territories, on one side, and the suicide bombers on the other. They do not dare to talk about reconciliation when the extremists continue their violent actions.

The lives of Palestinians are dreadful not only because of the 37-year-old Israeli occupation, but also because of our internal conflict and the deteriorating security situation. I blame both the Israeli and Palestinian leadership for the misery that afflicts us.

Shares