The belated North American premiere of Zhang Yimou's 2002 film "Hero" this past May was preceded by an inadvertent moment of hilarity. The occasion was a tribute to Zhang at the Coolidge Corner Theater in Brookline, Mass. (I was there as one of the speakers at an award presentation to Zhang the previous night). Before the film began, it was announced that the American distributor, Miramax, would be using infrared spyglasses to scan the crowd and make sure no one was surreptitiously videotaping the film.

The Coolidge, a beautifully restored Art Deco treasure, was lucky that there were still dry seats in the house following the announcement. The audience was laughing because they knew that "Hero," the highest-grossing film in the history of Chinese cinema, has been available for months on imported DVDs on both the Internet and in any Chinatown video store. That's how most Chinese-Americans see Chinese and Hong Kong film. It's also how I, and most American critics I know, tired of waiting while Miramax changed the release date again and again, first saw the 2002 film.

To American fans of Asian cinema, the news that Miramax has acquired rights to any Asian film is an occasion for mourning. By now the studio has assembled a consistent track record of re-cutting, dumping on the market, or simply not releasing the Asian movies it acquires. Jackie Chan's "Rumble in the Bronx" and "Supercop" were cut. The 2000 Thai film "Tears of the Black Tiger," a hit at the Cannes film festival, has never been released by Miramax. The U.S. release of "Shaolin Soccer," the biggest hit in Hong Kong history, was delayed and delayed before being dumped in theaters last spring shorn of 20 minutes. (At one point, the studio considered releasing it dubbed. Luckily, subtitled and complete versions are available on import DVD.) "Infernal Affairs," a Hong Kong police thriller so popular it has already spawned two sequels, has been bumped from Miramax's August schedule, though it's scheduled to be released Sept. 29. Next week's release of "Hero" has been postponed so often that Zhang's latest movie, "House of Flying Daggers," starring Zhang Ziyi, has already played Cannes in May and will follow "Hero" into theaters in December (Sony Pictures Classics is releasing it).

The martial-arts drama "Hero" is a departure for Zhang, following the "pictorial" style evident in historical epics "Red Sorghum" and "Raise the Red Lantern," and his tentative stab at genre filmmaking, "Shanghai Triad." That movie wasn't entirely free of the stateliness that can make his earlier films static but the gangster milieu perked it up, and it had a remarkable turn by Gong Li as a petulant cabaret star. The combination of brattiness and hauteur was much more compelling than the near immobility of her earlier performances for Zhang.

Eschewing the lavishness that had come to characterize his films, Zhang made two dramas on a small scale (though not emotionally), "The Road Home" and "Not One Less," each worthy of inclusion in the humanist tradition of filmmaking, whose masters are Vittorio de Sica and Satyajit Ray. The films did not stir as much excitement here as Zhang's earlier films yet they are among his very best work.

"Hero" clocks in at under 100 minutes, but in terms of sheer spectacle, it's epic. The story of a professional assassin working to kill the emperor who dreams of uniting all of China's warring clans is a sumptuous martial-arts tale that is both subdued and stirring. Zhang has put together what is possibly the most glamorous cast ever assembled for a martial-arts film. Jet Li plays the hired assassin, Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung a pair of warrior-lovers, and Zhang Ziyi their pupil. Shot in drenched greens and golds and reds by the great cinematographer Christopher Doyle, "Hero" is gorgeous to look at, and the story is the most sheerly involving and satisfying Zhang has yet made.

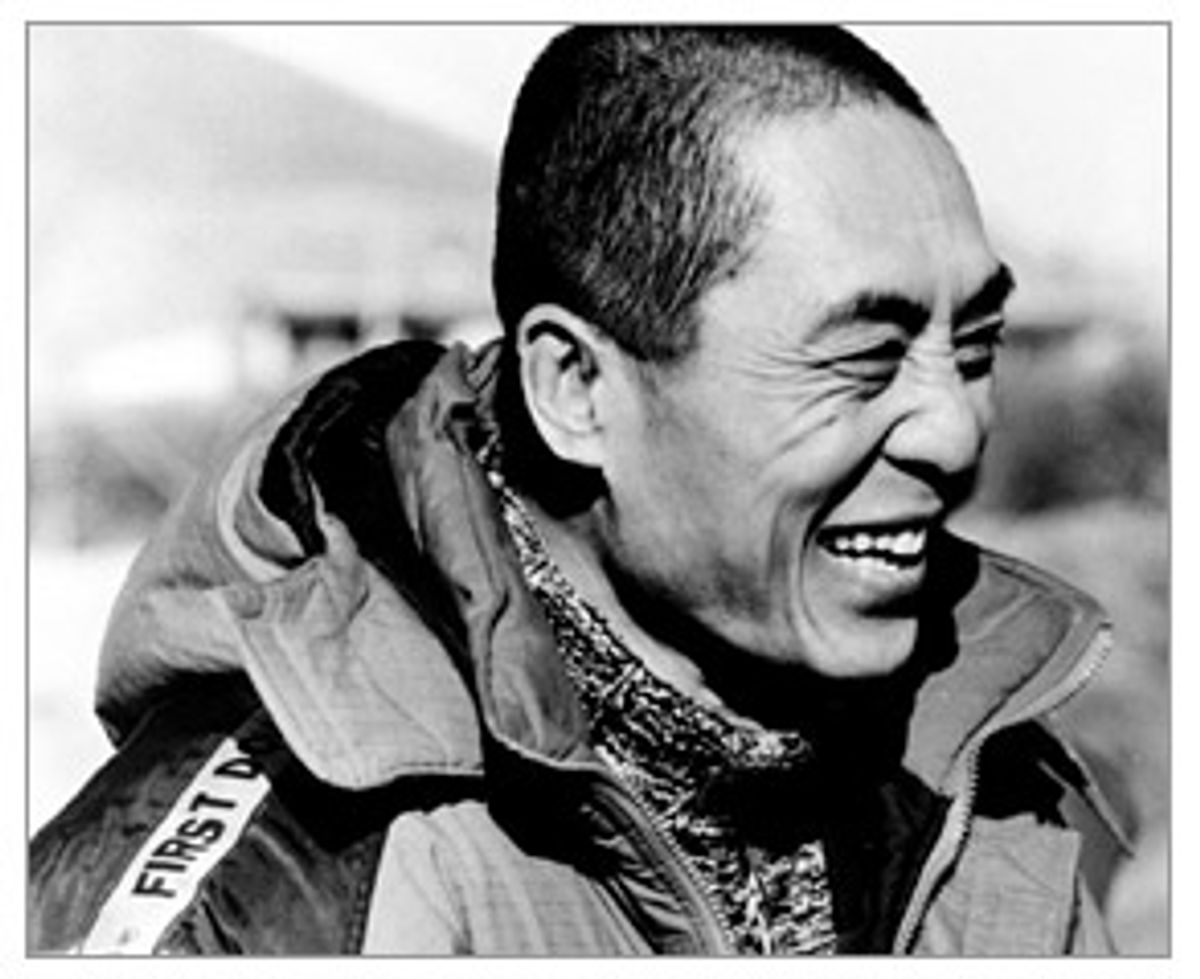

In New York to promote "Hero" in May, Zhang talked to Salon through his interpreter. Reflective and quiet, Zhang would not be lured into a discussion of Miramax's handling of "Hero"; you get the feeling such things are, for him, a distraction. He was much more open about how his lack of experience in the martial-arts genre did not dampen his wish to do something different.

Charles Taylor: It's taken a great deal of time to see "Hero" in the U.S. Could you explain the holdup?

Zhang Yimou: Since this film was sold to distributors all over the world, each distributor, in this case Miramax, has its own strategy. I will not get involved in Miramax's strategy about that, but I told them I will try my best to help with the publicity. Jet Li said to me, it will be a pity for the United States, because most of the Chinese people here watch DVD, so we have lost U.S. dollars.

CT: It's been available for months at video stories in Chinatown.

ZY: Nearly all Chinese people in America have seen this film.

CT: I hesitate to call this a martial-arts film because of all the quiet space in it. But it's still a very different type of film for you. What did you want to avoid from what we think of as classic martial-arts movies and what traditions did you want to honor?

ZY: Martial arts in Mandarin is wuxia. It's a very unique, cultural Chinese thing. We can find it in novels, comic books and film. So every Chinese knows about the concept of wuxia. Wuxia is talking about creativity, imagination. Everyone's imagination is different. It's something I can create. What I have in mind about the fighting is that it has to be poetic, traditional, beautiful in the manner of Chinese culture and literature. My wuxia has to mesh with the natural environment, maybe a drop of water, the leaves. Fighting has to be meaningful and special. With "Hero" I may not know about martial arts fighting, but I'll still show it according to my feelings.

CT: What's the difficulty of conveying lightning-fast moves while maintaining absolute clarity for the audience?

ZY: It's something to test the action director. I knew nothing about working with wires or how to shoot martial arts sequences. Before we shot the film I had to agree with the action director Siu-Tung Ching on the style and direction and feeling. It was quite interesting. Most of the time the action director led groups to shoot the action sequences while I led another group to shoot leaves or water drops or a river flowing, something Siu-Tung Ching wouldn't understand. Then, afterwards, I'd put them together. Later on, he'd find out that something that seemed irrelevant to him would be intercut into the fight scene.

CT: The characters in the film are able to control the physical world. That seems to me a dream for movie directors, to be able to control the world in front of them. Do you see any parallels between them and the role of the director?

ZY: Actually, I didn't think of that. Those abilities are typical of martial arts characters who are the No. 1 or No. 2 best fighters in the world.

CT: The close-ups of the actors' faces here are very beautiful. And you're working with some of the most expressive actors in Asian film -- I'd say in movies today, period. What's the preparation that occurs between actor and director before shooting a close-up?

ZY: I discussed the use of the shots beforehand with the [director of photography, Christopher Doyle]. I prefer using extreme shots. I like close-ups followed by a wide shot with skies or grass or soldiers. When I'm editing, I like this kind of arrangement. That's why I shot so many close-ups of the actors. Most of them are face to face. To an audience it seems like the actors are right in front of them, looking into them. I think that this kind of arrangement can convey more of a dramatic feeling and increase the tension. Most of the time before I shot the close-ups, I'd tell the actor and tell them they had to think of something because I needed something from them in that shot. And I'd tell them that the shot that would follow their close-up would be a wide shot, maybe of clouds. It may not be meaningful but I'm thinking that I'll put that shot after it.

CT: Do you see a thread through your films?

ZY: I haven't thought about it. I've always tried to do movies in different genres because I like changes. Every time, I want to do something that's different from my previous movies.

Shares