“Osama bin Forgotten” — that’s the joking way some Americans referred to the terrorist leader behind the Sept. 11 attacks after President Bush suddenly and utterly ceased to speak his name in early 2002. Osama bin Laden had slipped through U.S. fingers in the battle of Tora Bora and disappeared into the mountains around the Afghan-Pakistani border. Presumably, he’s still there and perhaps even now handing down orders via personal messenger for fresh attacks on Americans. (He has long since abandoned his satellite phones after learning that Western intelligence agencies could monitor the signals.)

For a man who, whatever George W. Bush might wish to the contrary, still casts a long and ominous shadow across the imagination of the American public, bin Laden remains an enigma. Compared with Saddam Hussein, the guy Bush tried to offer as a substitute bogeyman, bin Laden is practically a blank. We read about Saddam’s taste for vulgarian luxuries and the depredations of his troglodyte sons in fine detail; no one even seems to know exactly how many wives bin Laden has (although he’s said to have fathered 11 children by the first — so he must have quite an entourage).

“Osama: The Making of a Terrorist,” by Jonathan Randal, a former Washington Post reporter and longtime Middle East correspondent, promises to fill in the gaps. Randal spent several years researching bin Laden after the east African embassy bombings in 1998. He’d even made a half-hearted attempt to interview bin Laden before that, in Sudan, at the prompting of unnamed American officials, but was rebuffed. In the end, as Randal confesses up front, he never got his interview (bin Laden hasn’t met with a Western journalist since 1998), but he’s scoured all the available documents and coaxed bits of information out of his many sources in the region.

I wish I could say that all this has led to remarkable revelations about bin Laden’s history and character, but the truth is that there’s little here that hasn’t appeared in print somewhere before. What Randal does provide, however, is reliable guidance through the clouds of bin Laden-related legend, rumor and disinformation. Unlike, say, Yossef Bodansky’s dubious “Bin Laden: The Man Who Declared War on America,” which became a bestseller after the Sept. 11 attacks, Randal’s book isn’t peddling a political agenda. Intelligence agencies surely possess more information about bin Laden than they have made available to the public, but what Randal offers in “Osama” is likely the soundest portrait incorporating what we know now.

“Osama” is also the most psychological treatment of bin Laden’s story, although it is only intermittently so. Randal laments his inability to “ferret out a coherent view of [bin Laden’s] character, especially of his early formative years,” but at least he has tried, unlike the counterterrorism wonks who usually write these books. “I was confronted by a series of oddities with little insight into how they might mesh together or not,” Randal writes, and for him the great mystery of bin Laden’s recent exploits is that he seems not to have welcomed martyrdom after the fall of the Taliban government in Afghanistan in 2002. The journalist fully expected the terrorist to die in a blaze of glory and secure for himself the supreme spot in the pantheon of militantly anti-American Islam. But, Macavity-like, bin Laden eluded his enemies again.

From the beginning, bin Laden’s life was a tangle of contradictions. He is the scion of one of Saudi Arabia’s richest and most prominent families, but then again his family are outsiders among the insiders and Osama himself is an outsider among them. His father, Mohammed, was a Yemeni who walked with his two brothers from their homeland, in the region called the Hadhramaut, to Mecca, a grueling 1,000-mile trek. There, the hard-working Mohammed endeared himself to the ruling elite and became the Saudi kingdom’s preeminent building contractor, despite never learning to read or write.

Osama himself is merely one among Mohammed’s 24 sons (the exact number of his siblings appears open to doubt; Randal says there are 51, but the 9/11 commission report has the total at 57). His working-class Syrian mother comes from a family of Alawites, a heterodox Muslim sect disdained by the majority Sunni Muslims in Syria and considered “polytheists and apostates” by the fundamentalist Wahhabi Sunnis who prevail in Saudi Arabia. Mohammed bin Laden was an observant Muslim (sometimes described as “pious”), but according to Randal, “neither by upbringing in Yemen, nor by inclination, a Wahhabi.” Why the son so vigorously embraced a faith alien to his parents remains unknown; perhaps he wanted to fit in better with the Saudi elite, which would be ironic considering where his faith has taken him.

Mohammed soon tired of Osama’s mother and saw to it that she was married off to another Hadhrami who worked for him. Osama remained close to both his mother and stepfather, but there are rumors about his legitimacy. A Spanish woman who claims to have befriended Osama during a brief boyhood visit to England told Randal that Osama believed his mother was “not a wife of the Koran,” and some mean gossip going around Jeddah characterized him as “son of the slave,” that is, a child born out of wedlock to a servant. Nevertheless, Osama’s father raised him as his legitimate son, putting him to work early on in the family business and teaching him how to live rough in the desert, one of those character-building exercises to which certain fathers are prone. Mohammed died in a plane crash when Osama was 10, and he and his brothers became the temporary wards of the royal family.

Unlike many of his siblings, who traveled widely and attended Western boarding schools and colleges, Osama remained unworldly. He has rarely left the Muslim world and chose to study business management in Saudi Arabia because, according to Randal, he wanted to stay near his mother. Even after he married for the first time, at age 17, he and his bride chose to live with his mother and stepfather instead of setting up their own household.

Randal dismisses as “fanciful” persistent rumors that Osama indulged in a youthful playboy phase in the notorious nightclubs of Beirut. (There is even more unlikely gossip about escapades in London and other far-flung locales.) “The most charitable interpretation” of such accounts, he writes, “is that they confused Osama with his brothers or rich Saudis out on the town.” As Randal points out, civil war had begun to ravage Beirut before Osama was 18, and by all accounts, bin Laden was serious, conscientious, quiet and, above all, pious from childhood on.

Randal finds an old soccer buddy of bin Laden’s who recalls being gently if persistently urged by Osama to attend mosque and make daily prayers more regularly. Bin Laden would stage quiz competitions among his teammates with questions on the Koran and sharia (Islamic law), but would distribute the cakes he had brought to the losers as well as to the rest. Saudi youth, bin Laden feared, were being led astray by the Western vices made so available by oil-boom money, but he was not preachy. “He sort of hoped you would follow his example,” the friend told Randal, “but if not, you were still good friends. He had a very strong, quiet, confident and effective charisma.”

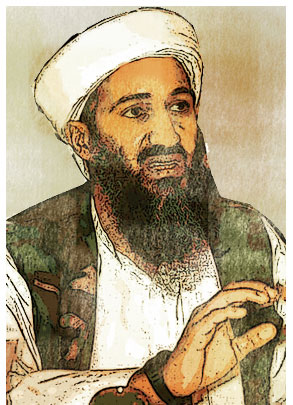

The nature of bin Laden’s charisma is one of the more fascinating questions Randal’s book elicits but never addresses. Bin Laden’s emergence as the world’s leading terrorist seems to have surprised many experts on the region, including Randal. At one point, Randal recalls looking at a photograph of bin Laden and thinking “that his face seemed somehow divided into a feminine top half and a masculine bottom.” The observation is revealing, even though Randal doesn’t take it much further.

Everyone who knew the young bin Laden characterizes him as soft-spoken, well-mannered and considerate, for all the fervency of his faith. People liked and often respected him, but few considered him a leader. He was seen primarily as a wealthy supporter of tougher men, and eventually as a financier rather than a director of terrorist groups, without either the scholarly chops or the aggressive manner to run things himself. Prince Bandar, the Saudi ambassador to the United States, remembers being thanked by bin Laden for the Saudi assistance to the Afghan mujahedin against the Soviets, and thinking, “He couldn’t lead eight ducks across the street.”

Certainly the Afghan war transformed bin Laden — it changed his life. But bin Laden’s countrymen and the people around him were slow to notice how much loyalty he commanded among the many Muslim foreigners who flocked to his training camps in Afghanistan. They celebrated his courage in a battle defending the mujahedin camp at Jaji against a Soviet attack in 1986 but also — and this, unaccountably, Randal never mentions — for his kindness and generosity to the fighters and for his willingness to share their primitive living conditions despite having been born into great wealth. The collection of virtues for which he was admired by his followers — humility, sacrifice and compassion as well as bravery — may seem to Westerners to possess a distinctly Christian aspect.

For years, bin Laden simply didn’t conform to the macho Arab notion of a major player. He lacked the imperious intellect of a mullah and the strutting bombast of a warrior king. Possibly this is why he was underestimated for so long by people in the region and the Westerners who listened to them, and possibly this is why Randal regards him as such a puzzle.

Osama emerged from the hardships of the Soviet-Afghan war a changed man, with a confidence that eventually blossomed into a lethal fanaticism. He believed — falsely, according to Randal and pretty much anyone else who knows much about the conflict — that his mujahedin drove the Soviets out of Muslim Afghanistan. He proceeded to stir up trouble in Saudi Arabia by urging a first strike against Saddam Hussein’s secular Iraq, which he considered an intolerable threat to the kingdom and the two holiest cities of Islam, Mecca and Medina. (This is only one of many details that make the notion of a real collaboration between al-Qaida and Saddam farfetched.)

When, just as he had predicted, Saddam invaded Kuwait, bin Laden tried to persuade the royal family that his motley band of mountain-fighting jihadists could defeat Iraqi tanks in the flat deserts of Kuwait. “We will fight them with faith!” he famously proclaimed, but the Saudis were unconvinced and chose the infidel Americans as their champions instead. This infuriated bin Laden and caused a second personal revolution: he had become the implacable enemy of the house of Saud, who in a rare move, revoked his Saudi citizenship.

Bin Laden then spent the early ’90s in Sudan, at the invitation of the silver-tongued, Sorbonne-educated and infinitely wily cleric Hassan al-Turabi, who was running things after masterminding the overthrow of the elected government from a jail cell. Eventually, Turabi (a character worthy of Shakespeare), under pressure from the United States, double-crossed bin Laden and ejected him from Sudan with very little notice in 1996. This was Osama’s third revelation; the focus of his animus had become the United States: He now understood it to be the source of everything that outraged him, from his humiliating ouster from Sudan to that most galling violation, the stationing of infidel soldiers in the holy land. His next major terrorist attack after his return to Afghanistan was the 1998 embassy bombings.

Disappointingly, Randal offers little information about Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Egyptian surgeon and terrorist leader who became bin Laden’s right-hand man in the late 1990s. What is the nature of their relationship? A defector from the Sudan period reported plenty of friction among al-Qaida followers there over the differences in salaries between Egyptians and the members from other countries. The Egyptians were paid sometimes twice as much — why? Randal repeatedly describes bin Laden as a “skinflint,” more likely to provide seed money to terrorist operatives than to fund entire actions from start to finish. (Once in-country, the operatives would have to fend for themselves and often fell afoul of law enforcement while attempting scams and petty theft.) So what made the Egyptians worth so much?

Randal is also of the conviction that the Sept. 11 attacks represented a rare “splurge” for bin Laden. Americans may have marveled at how little it cost al-Qaida — initial estimates were $500,000 — to achieve so much carnage, but as Randal points out, “Americans alone would find that a small sum. In fact, 9/11 cost exponentially more than any of Osama’s previous operations.” (The FBI later reduced the estimated cost to somewhere between $175,000 and $250,000.) The spectacular, world-changing horrors of Sept. 11 no doubt proved to the penny-pinching bin Laden that you get what you pay for.

This may also be good news for bin Laden’s targets, since there are signs that al-Qaida is in financial trouble. Randal reads much signficance into an unusual demand from two senior al-Qaida members, Khaled Sheikh Mohammed and Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who before their capture in Pakistan tried to extract $1 million (“later scaled back to a paltry $17,000”) from an Al-Jazeera reporter in exchange for an interview. He also passes on rumors that bin Laden and Zawahiri have quarreled over where to focus al-Qaida’s attentions in the future.

There are revealing tidbits about bin Laden that appear in books like Steve Coll’s “Ghost Wars” and not in “Osama” — such as bin Laden’s effort to be a good Muslim by equally distributing his visits among his wives. Does Randal discount such stories, or did he simply miss them? A more in-depth consideration — even if it’s just speculative — of bin Laden’s private life would be far more welcome than Randal’s long and largely irrelevant chapter on Algeria. (It seems to indicate that this book wasn’t originally conceived of as a biography of bin Laden, and in fact the result can’t honestly be called that.)

A soft-spoken man who seeks the spotlight, a well-mannered mass murderer, a son of religious moderates turned hardcore fundamentalist, a fugitive from the world’s greatest army with wives and children that possibly number in the dozens (where are they?), a warrior ostensibly resigned to martyrdom who cheats death again and again — you could cover pages with lists of Osama bin Laden’s contradictions. Add to that that he’s the enemy the Bush administration can’t seem to remember, and the rest of us can’t afford to forget.