There was no "imminent threat" to the United States from Iraq. Then there was no strategy for building a new Iraq. Our closest allies and international help were "marginalized" and "ignored." "The Bush administration was never willing to commit anything like the forces necessary to ensure order in postwar Iraq." "Hubris and ideology" ruled. When chaos and insurgency overwhelmed "naive assumptions," the blunders were "compounded" by a further refusal to recognize reality. "The obsession with control was an overarching flaw in the U.S. occupation from start to finish." When faced with a harsh choice between "legitimacy and control ... the U.S. administration opted for the latter whenever the tradeoff presented itself." Now, "Iraq is more dangerous to the U.S. potentially than it was at the moment we went to war."

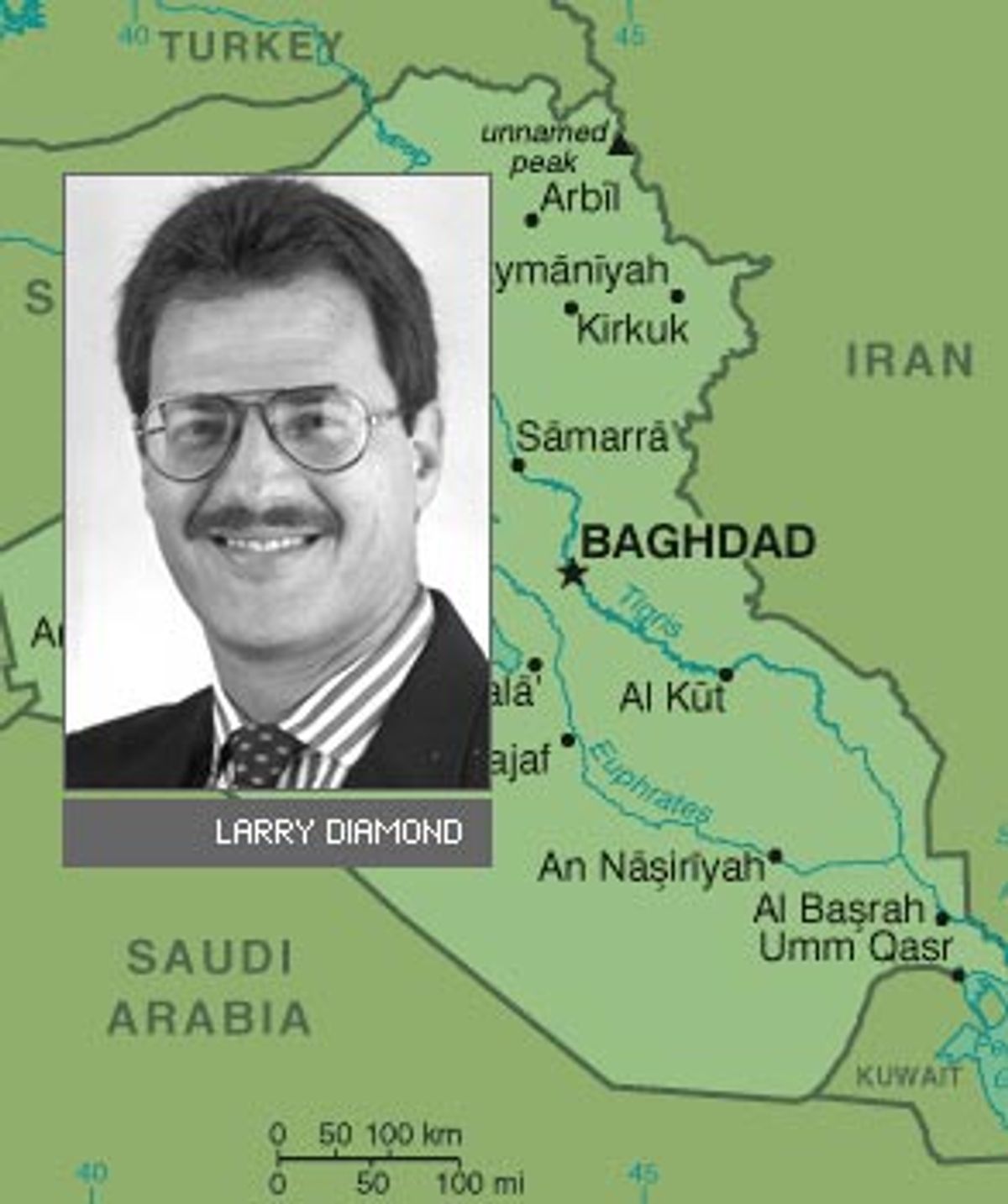

These are the reluctant judgments of one of the key U.S. officials who participated in the highest levels of decision making of the Coalition Provisional Authority. In an interview with me and in a forthcoming article in Foreign Affairs, Larry Diamond offers, from the heart of Baghdad's Green Zone, an unvarnished firsthand account of the unfolding strategic catastrophe.

Diamond, a scholar at the Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank located on the Stanford University campus, was personally recruited to serve as a senior advisor to the CPA by National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, who had been the Stanford provost.

Once he arrived in Baghdad, Diamond observed "a highly centralized decision-making process. There were Americans with decades of experience in the region who were not consulted or integrated into decision making, Foreign Service officers up to the level of ambassadors." The neoconservatives in the Pentagon were in charge and CPA head Paul Bremer "was the agent more of the Pentagon than the State Department." The Pentagon cut State out because the neocons viewed State as "not onboard" ideologically.

The British were regarded as warily as was the State Department. British Ambassador Jeremy Greenstock was systematically shut out. "When I was in meetings where decisions were made," says Diamond, "I don't recall seeing Greenstock there. He wasn't in the inner circle. There was frequent communication at the levels below Bremer between Americans and Brits. But in terms of the final decision making on the key issues, I never saw much evidence that they had the opportunity to weigh in." When British officials in Basra urged local elections there, "they were vetoed," he says. "And it would have helped. I think if the British had been listened to it might have been better. They had a history with this country."

The United Nations was considered useful only as a rubber stamp to approve the flawed decisions. According to Diamond, there was little desire to share power. After the Aug. 19, 2003, bombing that killed 22 U.N. personnel, "the organization felt that they suffered this trauma and for what? They were so ignored, they felt used. The combination of the risk and the trauma with the lack of impact and consultation left the organization feeling wounded." But when U.N. representative Lakshmi Brahimi appeared this February he negotiated the standoff between Shiite leader Ayatollah Sistani and the United States. "The reasons there are six women in the cabinet, corrupt members were jettisoned, and the ministers are regarded as able and serious have a lot to do with the U.N. team. It's indicative of what we could have accomplished -- one of the big strategic mistakes of the Bush administration."

"There are so many bungled elements," says Diamond. "We haven't had a strategy from the beginning for dealing with Muqtada al-Sadr. We were flying blind from the start. The result was we didn't neutralize him early on. You don't do it piecemeal. We had to shut off his funding from Iran. We didn't do that."

And in Fallujah, after the murder of four American contractors, the U.S. military pounded the city and then suddenly withdrew. "We now have a terrorist base in Fallujah. We've decided to live with this. The Bush administration looked at the political cost, at what would have been necessary to destroy this terrorist haven. The ultimate irony is that a country not an imminent threat to the security of the U.S. is now, in some localized areas, a haven for the most dedicated, murderous enemies of the U.S. -- including al-Qaida."

In Iraq, contends Diamond, the United States cannot escape from its own trap without even more ruinous consequences. "If we walk away the place falls apart disastrously -- Lebanon on steroids. Americans are not only a bulwark against Lebanon-style civil war. They are a stimulus for both nationalist and Islamic fundamentalist mobilization. We need to reduce that stimulus and provocation without robbing the new Iraqi state of the bulwark it needs. We are significantly worse off strategically than we were before. There are really no good options."

Fallujah remains under terrorist control; insurgents run rampant even beyond the Sunni Triangle; the number of U.S. soldiers killed climbs toward the 1,000 mark; the Iraqi army, disastrously disbanded by the CPA, is slowly being reassembled and trained. But in the meantime, the American campaign is consumed with false charges made by a Republican front group about the medals that John Kerry earned with his own blood in a war more than 30 years distant. The arrogant and incompetent blunders of the Bush administration in Iraq are not debated. On the eve of the Republican Convention, Bush burnishes his image as a prudent and reassuring leader. The lethal realities of his "hubris and ideology" are for the moment off the screen. Mission accomplished.

Shares