Lazing cows dot the rolling hills of the picturesque Willamette River valley, and the air smells sweet of grass and manure. But this sunny image masks a grim reality for dairy workers like Arturo Ramirez. For six years, Ramirez's duties included maintaining a pump that sprayed liquid dung onto the fields as fertilizer. To get to the pump, he had to walk waist deep in manure across a pit as long as a swimming pool. Wading through manure isn't like walking through water: The sludge is heavy, the rotten-egg smell of hydrogen sulfide rises off the slick surface, and if you're unlucky, you can slip and drown.

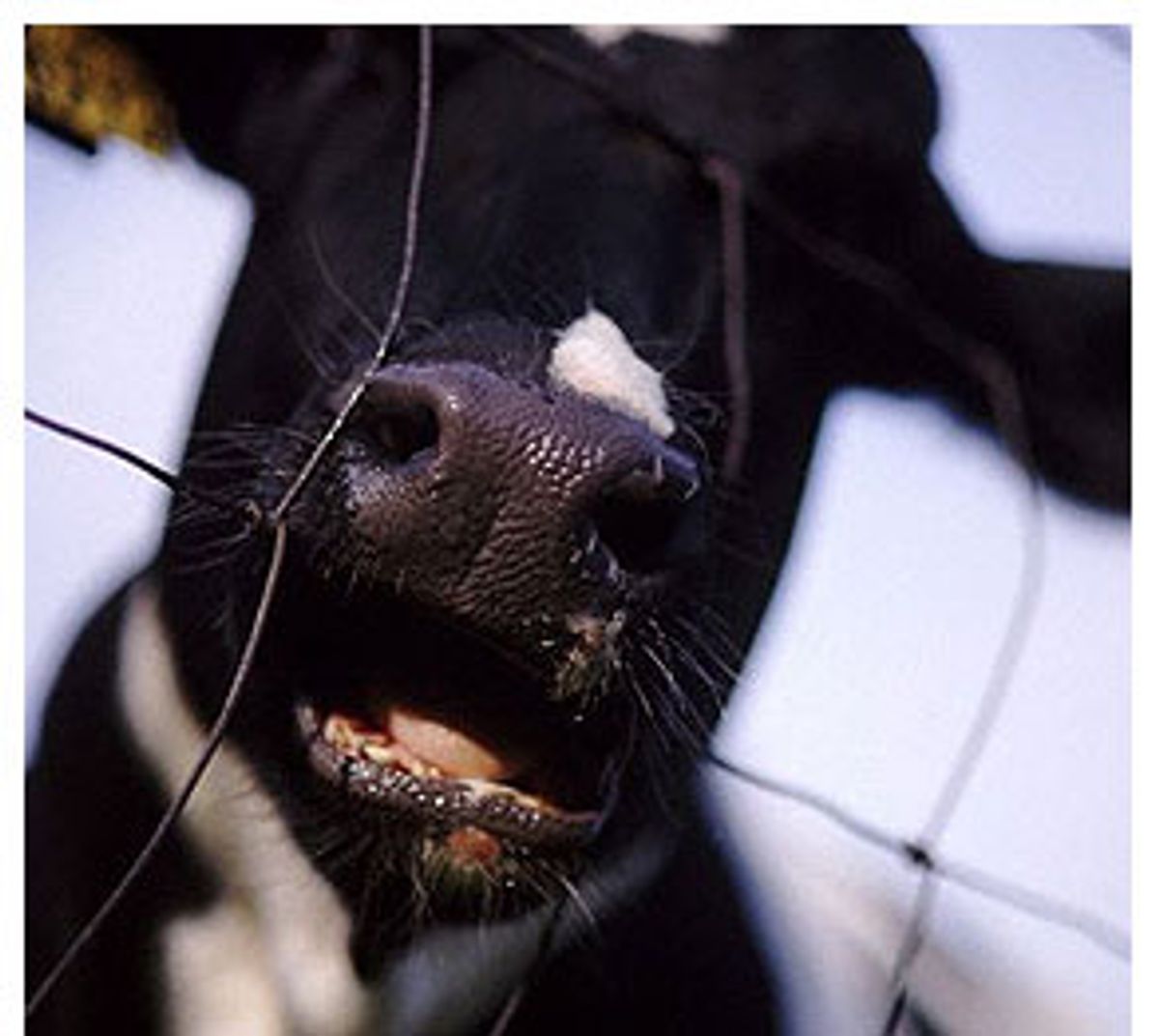

Ramirez didn't die in the manure pit -- a fate met by three workers in California -- but as he waded through the waste of 380 cows, it slid into his knee-high boots. Because it's impossible to completely scrub away the bacteria from manure, Ramirez passed a skin infection on to his wife and her two daughters. "I felt like a slave; it was like my boss had a whip," says Ramirez, 27, who relocated to this lush rural valley from the desert of central Mexico.

Arturo Ramirez is not his real name, and he has a new job at a different dairy, but he worries he'd be fired if his boss discovers he has talked to a reporter. Ramirez can't afford to be out of work. When his father died 12 years ago, he crossed the border through the Arizona desert to find work to help support his mother and four younger brothers and sisters. Without the $400 he sends home every month, his family would barely survive.

It's not an easy sacrifice: Ramirez works 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week, for minimum wage and no overtime pay. Until this past February, when Oregon passed a new law, dairy workers were afforded no lunch or rest breaks. In more than 40 states no such law exists, leaving many employees no choice but to eat lunch while working. Ramirez, like other dairy workers, is regularly kicked by cows and is exposed to toxic gases in the manure, such as hydrogen sulfide, that may cause permanent neurological damage.

"I worry every day that I will break my hand or get hurt, but I never say anything for fear I'll lose my job," says Ramirez, who uses a fake Social Security number. "No American would do this job. This is a shit job, for shit money." Yet Ramirez, like most other dairy workers, has few other employment options besides agriculture. Since the vast majority are non-English-speaking immigrants, and none are unionized, relatively few complain to state or federal agencies for fear of losing their jobs or being deported, according to legal aid organizations in Oregon and California and the United Farm Workers of America. Even if they were speaking up about working conditions, fighting for protection would still be an uphill battle.

The workers, who on average make between $5.15 and $7.06 per hour, can't compete with the wealth and political power of their employers. In 2002 the dairy industry gave more than $5 million to state and federal campaigns. "Dairymen have a good ear when it comes to approaching the legislature," says George Gilman, an Oregon state representative and recently retired dairy owner. "The industry is really well represented in legislators around the United States. There's enough people that understand the challenges of our industry."

The federal government collects no statistics about dairy workers, no advocacy groups work solely for dairy worker protection, and federal law has lagged as family farms have been consolidated into more-corporate enterprises. This failure to develop and enforce even the most rudimentary health and safety standards goes unnoticed because immigrant workers are among the most exploitable members of the workforce. "Despite the fact that the conditions amount to near slavery, dairy workers tend to get ignored," says Brent Newell of the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment, based in San Francisco. "This industry is extremely powerful." And with consumers mostly concerned about the availability of cheap milk and cheese, there's no public clamor for an improvement of the dairy workers' labor conditions. Says Charlie Tebbutt of the Western Environmental Law Center: "Who's going to fight milk? It feeds and nourishes babies; it's Chevrolets and apple pies."

Dairy work is a repetitive and debilitating dance. Hundreds of times a day dairy workers attach hoses from automated milkers to the teats of cows. They also lift hay bales, carry or shovel grain, and attach equipment to tractors. All these motions can cause chronic sprains, strains and lower back pain.

Over time, repetitive motion injuries can cause permanent, crippling damage. "While these men are young, if they continue this work for the next decade they can end up with lifelong pain and permanent disability," says James Meyers, an agriculture and environmental health specialist at UC-Berkeley's School of Public Health. "These types of injuries are very painful, very limiting and very expensive to treat. This side of fatalities, musculoskeletal disorders are the most debilitating occupational injury."

Aside from chronic problems, dairy workers often break bones from being kicked by cows or from slipping in the muck-covered concrete floors of dairy barns, explaining why the rate of injury on dairy farms is higher than in all other types of agriculture and all private industry, according to a 2003 report in the Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health. Furthermore, dairy workers exposed to toxic-gas-releasing manure may experience nausea, diarrhea, sore throats, stress and alterations in mood, according to a 2000 study published in the Journal of Agromedicine.

Workers are not getting the treatment they need, says Tillamook County (Ore.) Health Department case manager Diane Barnes. Immigrant workers rarely file workmen's compensation insurance claims for fear they will lose their jobs, Barnes says. Such insurance covers medical costs and wages lost due to injury-caused time off, but they also cost employers as much as $2,000 per worker. "The guys with documentation don't work in the dairies, and there's a huge fear of retribution because there are people just waiting to take their job," says Barnes. "Whether spoken or unspoken there appears to be some kind of agreement that they aren't going to make waves. Everyone seems to acknowledge that the employer has them there to make money, not cost money."

Yet workmen's compensation claims are one of the prime ways that the Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the state agency charged with protecting workers, prioritizes what companies to investigate. With only 75 field officers to regulate more than 80,000 employers in Oregon, a state more than twice as large as New England, the agency admits there's no way it can be a watch-dog. Due to the dearth of worker's comp claims, last year the agency investigated only 17 of the state's 343 dairies. That figure earns Oregon a better than average grade: In 2003, state and federal agencies inspected 51 of the nation's 86,300 dairy farms.

"There's no way we can be everywhere at once. We want employers to be self-sufficient," says Trudi Tyler, an Oregon OSHA compliance officer. "We've gone a long way to create an atmosphere to not create an adversarial position within the industry."

Even when agents do conduct inspections, the regulations are marginal. Unlike the meat packing or construction industries, the dairy industry has no specific standards; nearly a century ago, Congress caved in to powerful Southern rural politicians and exempted agriculture from most worker-protection laws. As the farming industry has expanded into an industrialized enterprise, the laws haven't changed. Today, dairy owners are held to the same weak regulations governing farms, with no specific guidelines for how workers should be specifically protected from milking machines or general interaction with cows. In the 24 states that defer to federal regulations, dairies with fewer than 10 employees are exempt from inspections unless an employee dies or at least three people are hospitalized.

Indeed, basic labor laws found in other industries don't even apply to dairy industry workers. Like all other agricultural employees, dairy workers are excluded from the National Labor Relations Act. But because dairy work is year round, they are also omitted from the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act. Protected by neither of those two laws, dairy workers are exempt from overtime pay and the right to form a union or to confront an employer with workplace concerns as a group, and they have no general safeguard against employer misrepresentation. This makes dairy workers the least protected laborers in the country, says attorney Mark Wilk of the nonprofit Oregon Law Center.

"Dairy folks are legally in the worst of all worlds. There really is no federal law at all to protect them," Wilk says. Nearly one-third of his 89 clients are Hispanic dairy workers, and Wilk says their Mexican and Guatemalan origin is part of why the laws remain weak. "This is the last bastion of feudalism. The ugly reality of the world that my clients live in is shocking. We're the richest country in the history of the world. We can do a better job making sure all workers have minimum standards of decency."

Over the craggy Cascade Mountains, the arid plateau of eastern Oregon is a lonely landscape of sagebrush, power lines and ochre dust. Just south of the Columbia River, down a long narrow road, Threemile Canyon Farm stretches across 93,000 acres, housing 35,000 cows. This massive enterprise is one of the most extreme examples of the corporatization that has steadily been swallowing small dairies throughout the country. In just little over a decade, the number of dairies nationally has declined by half but the average size has increased by 73 percent.

A joint venture between R.D. Offutt, one of the largest potato growers in the country, based in Fargo, N.D., and John Bos Family Farms, a Bakersfield, Calif., dairy operation, Threemile Canyon Farm's three dairies produce 1.3 million pounds of milk per day -- enough to serve nearly the entire population of Idaho. Such size is a good business model: Threemile, which also grows potatoes and alfalfa and has a composting operation, generates an estimated $250 million for the local economy. Critics say the poor working conditions for the dairies' 140 employees help spell this fat bottom line. In rural Boardman, about 20 miles from the dairy, a group of workers just finishing an 11-hour shift spill into Gerardo Castellano's three-room apartment. As the smell of frying tortillas wafts from the kitchen and a young boy all belly and dark eyes runs through the room, the men fold their exhausted forms into sagging couches and explain in Spanish why they feel like second-class citizens.

They often work as many as 12 hours a day, six days a week, and are paid a weekly salary of $550. If there are 31 days in a month, they are not paid for the 31st day. While they would like a weekend, and more than one week off a year, they say if they miss a day, even for a family emergency or visit to the doctor, they will be fired. "We're disposable to them. We're like a machine. I don't think they see us as real people," says Julio Arturo Sepulveda. "I need this job. I feed my family with this job, but it's not right."

As the men joke and tease each other over who works the hardest, they all list the same woes: bruises from kicking cows, chronic coughs and asthma from the dust, achy joints, and lower back problems. Castellano, who once worked in an accounting office in Mexico, says, laughing, "Pick a place -- it all hurts."

Paradoxically, this trend toward corporatization may offer dairy workers a small slice of hope. No dairies in the country are unionized, largely because the majority of dairies are small, decentralized operations with only a handful of employees. Dairy workers at Threemile Canyon say that with numbers comes strength. In January 2003, a group of 100 dairy workers stormed the United Farm Workers local in southern Washington, outraged at sudden wage cuts, says Erik Nicholson, the union's regional director. Since then, change has been tangible. Union organizers, effective at beating the drums, have spurred articles in the local and regional media, written letters to Oregon legislators and the Mexican consulate, and instigated an OSHA investigation, which resulted in 12 citations.

Subsequently, the dairy has increased wages by $200 a month, provided health insurance to its workers, and has started to provide the required safety equipment and training for the use of hazardous chemicals, Nicholson says. "These guys have come to experience firsthand the power of collective action," says Nicholson, sitting on the tailgate of his truck, parked in Boardman. "Now they understand their rights and they're overcoming their fear."

Indeed the tone of the workers congregated at Castellano's apartment is miles from the hopeless and anxious tenor of isolated workers in western Oregon. Rather, their voices are strong and determined. "I have faced a lot of discrimination because I'm a union supporter, but I want to stay and fight until they understand that we have rights," Sepulveda says. He and 68 other workers recently settled claims against the dairy for failure to pay minimum wage. "I want the best for my kids, and so the abuses, the discrimination, it has to stop." Still the process is slow. After over a year of repeated attempts at negotiation, the company still does not recognize the union. It has hired consultants and lobbied at the state Legislature for a bill that would outlaw harvest strikes and allow farm owners to negotiate union contracts for an unlimited amount of time. According to the company, its size makes it a union target.

"It's economically efficient for them to try and unionize because we're a large-scale enterprise," says Len Bergstein, a spokesman for Threemile Canyon. The company has a letter signed by 100 dairy workers saying they don't want a union. "This is no more than a series of attempts to ruin a business enterprise that workers depend on." Industry insiders take a broader view, explaining that this fight is just part of the growing pains the entire industry has experienced over the past decade.

As Hispanic immigrants increasingly replace young family members or other local teenagers, dairy owners are working to meet the needs, such as insurance and benefits, of this new population of workers, says Agnes Schafer a vice president of the Dairy Farmers of America, based in Kansas City, Mo. "Throughout the U.S. we are going through an evolution of understanding," says Schafer. "Farmers in general are pro-Hispanic because it's economical and it's people who want to work and who value agriculture, but we're going through a cultural shift."

While the industry is not working on any legislative efforts that would supply insurance or other services to undocumented workers, industry lobbyists say that President Bush's proposal to grant some farmworkers citizenship would help. Yet in the short term there is little on the horizon that offers much solace for immigrant dairy workers.

Even if Threemile Canyon Farms is eventually unionized, the thousands like Ramirez who work in dairies with just a few employees will continue to work despite low pay and dismal conditions. "Back there [in Mexico], you work for $5 a day. All we had in my town was one donkey," says Ramirez, shaking his head at the memory. "My mom misses me; she cries sometimes when we talk on the phone, but I can't go back to Mexico. I'm afraid to die in the Arizona desert."

Shares