And the gold medal goes to Moral Ambiguity! The silver medal goes to Patriotic Hero Worship! The bronze medal goes to It's All the Americans' Fault!

All of the ethical contradictions, less-than-noble emotions and political enmity that haunt the Olympics, and Greece, in the age of performance-enhancing drugs came out last night at Olympic Stadium. I wasn't there -- I went to the stirring championship women's soccer match between the U.S. and Brazil, which I'll write about later -- but the news is in all the papers today. A stadium full of angry and disappointed Greek fans delayed the start of the men's 200 meter race for eight minutes, shouting "Hellas" and "Kenteris" and whistling derisively when images of American sprinters were shown on the screen.

For those who haven't been following the Kenteris saga, here's a quick recap. Costas Kenteris and Katerina Thanou were two little-known runners who shocked the world (and me) at Sydney by winning gold in the men's 200 and silver in the women's 100 meters. Kenteris was the first runner to win a medal for Greece in track since the 1896 Olympics. Those Olympic triumphs instantly turned the two athletes into national heroes. Kenteris was voted the most popular man in Greece; an Aegean ferry and streets were named after him; he got lucrative sponsorships. Then, just days before the start of this Olympics, it all came crashing down.

The pair, who had long been viewed by track insiders as extremely suspicious for a variety of reasons, missed a drug test and checked themselves into a hospital where they remained for five days, claiming that they were suffering injuries from a mysterious "motorcycle crash" that authorities doubt ever took place. They withdrew from the Games and are the subject of several investigations, including one by the top international athletics body, the IAAF, and by the Greek police.

The Greek public reacted with shock, outrage and a profound sense of betrayal. Nikiforos Mardas, a 30-year-old software product designer who lives in Athens, told me, "The people I spoke to said they felt like someone had spit on them." Consternation over the scandal distracted attention from the marvelous Opening Ceremony, and there was endless hand-wringing, accusations and soul-searching in the press. "We will never forget this insult," one Greek man was quoted as saying.

So why did thousands of Greek fans chant "Kenteris" and boo the Americans? Had the never-to-be-forgotten insult been forgotten in two weeks? Had Kenteris and Thanou gone from being disgraced to being victims?

Mardas, who was at the stadium last night, said, "A lot of it is tied to conspiracy theories -- the idea that the Americans are behind the whole doping scandal. I turned to one woman behind us and asked her why she was booing and she said, 'Well, we didn't invent drugs, did we? The Americans did.'

"A lot of people think the Americans engineered the drug tests. That goes along with the sense that everyone does it, so why blame the Greeks? It's all tied to a classic Greek trait, a persecution complex. The belief that everyone's against us -- whether it's the Europeans because we're close to the Middle East, or the Americans."

But why the chants of "Kenteris"?

"I think this was more about booing the Americans than cheering Kenteris," Mardas said.

Mardas added that he thought the people who were booing were those who had bought tickets to see their national hero (the event was sold out a year ago) and hadn't really thought out their actions. "I pointedly asked one man why he was behaving in such a petty way, and he didn't have an answer," Mardas said.

Belief that the all-powerful U.S., which is even less popular here than in most European nations, is pulling the strings is widespread. An art historian told me that it was widely believed that the U.S. had cut a deal with the IOC, wherein American athletes wouldn't have to take drug tests.

British journalist Dan Howden, who has lived here for five years and reported extensively on the doping scandal, said, "It's a very interesting issue because it goes to the heart of Greek identity. There's a real chip on the shoulder, a sense that 'the world is against us.' After Greece won the Euro 2004 [football championship], there was speculation that it might bring to an end some of this crippling fatalism. But then along came this [the Kenteris/Thanou scandal], and people can shuffle back into that comfort zone that it's someone else's fault."

Howden pointed out that lurid conspiracy theories about evil U.S. plotting have some basis in fact. "Look, on a serious level, it was made clear by senior figures in U.S. athletics that they were going to go after a lot of big names and they expected other countries, including Greece, to do the same. [Many top U.S. athletes were in fact banned from the Games for doping violations.] Kenteris and Thanou had been under suspicion. There was a quid pro quo."

Howden said that Greek anti-Americanism goes back to the most traumatic event in modern history, the bloody civil war between Communists and non-Communists that followed World War II. The U.S. intervened against the Communists and later supported the despised junta that ruled Greece between 1967 and 1974. President Clinton dispelled some of the lingering anger over the latter policy when he issued a guarded apology for it in 1999, but President George W. Bush's policies, in particular his invasion of Iraq and his pro-Israel tilt, have fueled more anti-U.S. ire.

But another Greek professional I spoke to said that the real Greek anger was directed against IOC head Jacques Rogge, anti-doping honcho Dick Pound and the whole system, not specifically Americans. "They booed the Americans because they were on the screen and because Kenteris wasn't running, not really because Greeks don't like Americans." He also said that Greece's everybody's-against-us trait was fading. "Twenty years ago, if this had happened, there would have been real problems," he said. "Today there aren't."

I witnessed some of the passions that are roiling Greece two nights ago at one of the more bizarre -- for an outsider -- athletic events I've ever seen: Greek runner Fania Halkia's already-legendary, but eyebrow-raising win in the 400-meter hurdles.

It should have been the feel-good race of the Olympics. A little-known Greek runner runs the race of her life and wins gold, restoring honor and pride to her wounded nation.

The only problem is that was the story line for Kenteris and Thanou, too -- and there are just a few too many similarities between the stories for comfort.

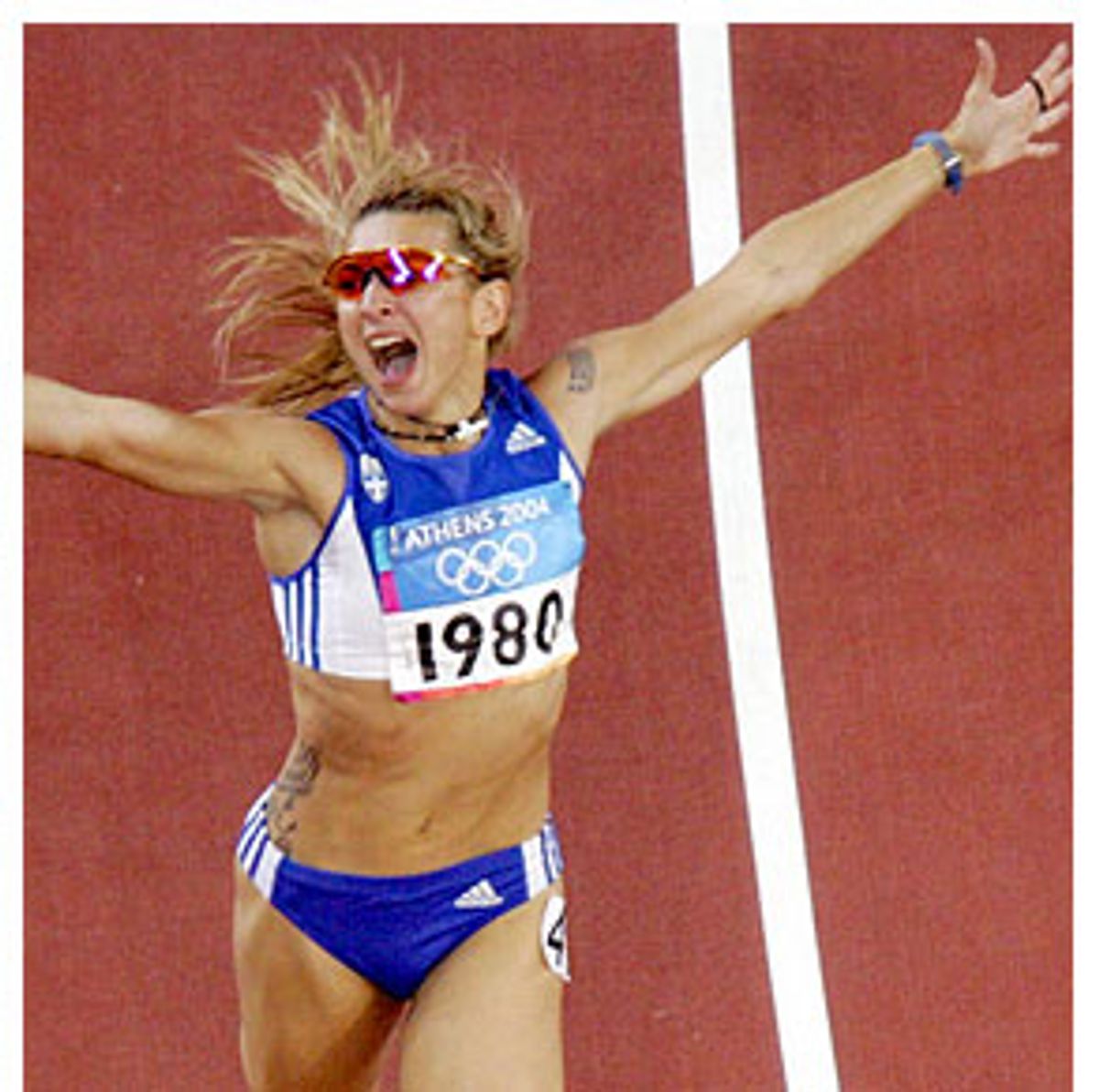

They're calling Halkia's triumph the signature event for Greece in these Games, the equivalent of Cathy Freeman's victory in the 400 at Sydney. People in the crowd went bananas. It's as loud as any crowd I've ever heard. "Hellas! Hellas!" they roared at the top of their lungs for several minutes, while a sea of blue and white Greek flags waved. Late into the evening, people were waving flags out car windows and honking their horns, celebrating the triumph.

The press went wild, too. In the English edition of Kathimerini, a leading newspaper, a photo of Halkia throwing her arms out in triumph after winning was splashed across the front page. The article said, "After the shock of the withdrawal from the Games of top sprinters Costas Kenteris and Katerina Thanou after they missed a drug test, this was supreme consolation for the Greeks." The tabloids had a field day. "Fania, Fania, Fania," one moaned. Another called her a "winged goddess" -- hokey comparisons to figures from classical Greece being just as popular here as abroad -- while yet another whinnied that she was a "wild steed that could not be controlled."

One paper's headline read simply, "Redemption."

But under the circumstances, redemption for Greece, of course, wouldn't just come from winning -- it would have to come from winning clean. And even as I stood there in the middle of the frenzied crowd, a little voice was saying, "Uh ... " And believe me, it's a drag to feel like the only one at the mass communal epiphany and national redemption-fest who's wondering if the whole thing is a scam.

Halkia's story is almost too good to be true -- and that's where that exasperating little voice comes in. She started out as a high-jumper, then took up the 400 but had little success. Frustrated by injuries and her limited success, she quit athletics to become, among other things, a broadcast journalist. Then she reentered the sport. As recently as six months ago, she was an unknown and mediocre runner. Her lifetime best in the 400 hurdles at the start of this year was 56.40 -- which would have left her dead last in last night's race. Even more remarkably, in March, the best she could do running a flat 400 was 52.90 -- slower than she ran over the hurdles last night!

Then, Halkia somehow got really good, really fast. In qualifying, she broke an Olympic record that had stood for eight years, smoking the field with a 52.77, as we all stood there with our mouths agape. She ran 52.82 for the gold. That means that in less than a year she improved her time by three and two-thirds seconds -- in a sport that measures improvement in half-second or even tenth-of-a-second increments, and where victory is often measured in hundredths of seconds.

Of course, it's possible that Halkia is simply a prodigy, a naturally gifted runner who trained hard and happened to develop extraordinary speed. There are probably other cases of top-tier track stars who cut 7-plus percent off their personal bests in less than a year, as she did. But not many.

As I watched Halkia's come-out-of-nowhere victory, it reminded me of nothing so much as Kenteris and Thanou's races in Sydney -- which were also touted as redemptive, miraculous and evidence of the great Greek spirit.

I'm all for the great Greek spirit. But maybe it would be better to kind of not talk about it for a while.

Halkia does not use Kenteris and Thanou's coach. She hasn't failed any drug tests (all the medalists are tested immediately after the event). And of course everyone is innocent until proven guilty.

However, it's not just Halkia's extraordinary improvement, but the fact that the whole Greek athletic system, from top to bottom, appears to have been caught up in a win-at-all-costs mentality, that leaves a sour and lingering suspicion.

The ludicrous "Run! The drug testers are here!" aspect of the story focused attention on Kenteris and Thanou, but the real story was that there was obviously significant official involvement in the doping scandal, from coaches and top athletics officials perhaps even to senior members of the government. It turned out that the two runners rarely competed at meets where they were likely to be tested, and that the Greek track and field federation routinely lied to international inspectors about athletes' whereabouts, preventing them from being tested. Something very fishy also seems to have gone on at the hospital, which obligingly kept the two stars out of reach for four days, when their "injuries" were clearly slight or nonexistent. What authority sanctioned or demanded this behavior?

Part of the answer to that question is found in the figure of Kenteris and Thanou's coach, Christo Tzekos. Tzekos is now facing investigations but the question is why it took so long: Everybody knew what he was up to. A former nutrition-supplement salesman (it was reported that Victor Conte, founder of the notorious American doping-implicated company Balco, e-mailed him earlier this year, warning him that a banned substance could now be detected by drug tests), Tzekos approached former culture minister Evangelos Venizelos with a proposal to prepare 150 Greek athletes to win Olympics medals, allegedly with banned substances. The plan was given the secret name "Korivos," after a sprinter in the first Olympics in 776 BC (and thus representing possibly an even greatest debasement of Greece's classical heritage than the Acropolis ashtrays on sale in the Plaka.) As the paper Athens News noted, "Serious questions remain about why Tzekos was not investigated after such a proposal, and what backing might have made him so confident as to make such an audacious overture."

It is also worth noting that medal-winning Greek athletes are rewarded with honorary military rank, and a salary that goes with it -- a system more than a little reminiscent of the old Eastern-bloc way of creating and rewarding victorious athletes. Howden points out that several of Greece's neighbors, like Bulgaria and Romania, have had state involvement in doping, and that Greece, a singularly schizophrenic nation (Patricia Storace's "Dinner With Persephone" gives an eloquent account of this) is faced with a choice: "Is it leaning towards its Eastern or Western tradition?"

The doping scandal is not going away. It has become a major political issue between the current Greek administration and the socialist opposition party, Pasok, with each side trading accusations that the other was responsible for the debacle.

Halkia, for her part, went on the attack when asked about drugs at the post-race press conference. "Why do people always want to say negative things about sport?" she asked. It wasn't drugs that carried her to victory but something higher: "I think the Greek soul is so great it can carry us to victory."

Halkia said she was moved that the first congratulatory call she got was from Kenteris. As for Kenteris and Thanou, she defended them, saying, "They were put against the wall, there was a firing squad. People imagined the wildest things."

She thus joined the growing number of Greek Olympians who have stood up for the two runners. Gold medalist walker Athanasia Tzoumeleka dedicated her medal to Kenteris and Thanou and 1500 meter runner Nandia Efendaki called on the crowd to "remember Kenteris" at the 200 meter race yesterday.

As for Kenteris himself, he made the ultimate power move, implicitly equating critics with the anti-Christ. When he emerged from the hospital, he said "At this time, all those who are crucifying me are those who would come and pose for photographs after every great success. But I want to add that after crucifixion comes the resurrection."

Unlike Kenteris, Thanou did not go so far as to compare herself to the Son of God, but she did engage in the time-honored tactic of wrapping herself in the flag: "I will continue to fight for myself and those who feel they are Greeks."

What's noteworthy in the rapturous reaction to Halkia's triumph here is the absence, so far, of any questioning of it. One might think that having just been through the patriotic-pride-to-massive-betrayal cycle, Greeks might want to wait a bit before enshrining Halkia among the immortal gods at Mt. Olympus.

But Howden thinks that all the hysteria, highflown rhetoric and rapture is misleading. "It's a statement of unity, but underneath it is a lot of doubt."

So what does one make of the Greek reaction to the Kenteris-Thanou scandal, Halkia's triumph and the crowd's behavior before the 200 race?

The embrace of Halkia is understandable: Most other people in the world would probably do the same thing. She hasn't been proven guilty of anything and everyone needs a hero. I just hope the Greek people don't get fooled again.

The booing of Americans, however, crosses a line. These are the Olympics, not the National Greek Patriotism Games. Patriotism and cheering for one's country are great; deriding other athletes or other nations, for any reason, is not. It's true that it's much harder for small countries to practice Olympic magnanimity and sportsmanship than big ones like the U.S., which win everything. But the Greeks are too warm and wise a people for such petty displays. The Greek soul shines brightest not when a sprinter wins a race, but when -- as happens thousands of times a day -- a volunteer smiles cheerfully at a visitor, or the crowd applauds the game efforts of a competitor destined never to win.

As for the ambiguous attitude toward Kenteris and Thano, that's trickier. Several Greeks have told me that everyone knows that they're guilty but that everyone also thinks that the whole moralistic fervor over drug testing is a scam, that everybody's using them anyway and the only real problem is getting caught. Accompanying this feeling is the belief that every country, not just Greece, is deeply implicated in the doping scandal. As a Greek shop owner told me when I expressed regret about the drug fiasco, "What can we do? It's the system."

In one sense, it's hard to argue with this. U.S. sprinter Shawn Crawford, for example, is coached by Trevor Graham, who is the U.S. version of Christos Tzekos: Six of Graham's former athletes have tested positive for banned substances. And Crawford sure does look ... large. Just as Marion Jones did when she got down in the blocks in Sydney. Jones, of course, is under a cloud of suspicion -- but there she was on the field the other night. Are Americans, or any other nation, really in a position to throw stones?

Maybe we are, maybe we aren't. We just don't know. The problem with the whole drug issue is that it's so murky, testing so erratic or poorly explained, and official and quasi-official involvements in doping so Byzantine, that this cynicism is partly justified. The shop owner was half right: the system is totally screwed up.

The other night, drinking a beer by the big screen outside the stadium, I met the British bronze medal winner in women's pair sculls, a refreshingly unpretentious Cambridge grad named Sarah Winckless, who said that testing was stringent but that she was sure many athletes were escaping the doping tests. She referred to one competitor "who's really skinny and incredibly strong. Hmmm."

More drug tests than ever have been administered here, and more athletes than ever are being stripped of medals and caught using banned substances. But one gets the sense that testing is not universal, that there's an element of chaos and chance in it. That sense undermines one's confidence in the system.

Still, it's a little too easy to throw one's hands up and say "they all do it, who cares?" The problem is, until someone figures out how to shine more light on this murky issue, even if only to make it clear what will always be murky and what can be illuminated, it'll be hard to argue with the cynics. And we'll keep hearing that little voice wondering whether athletes like Fani Halkia achieve their feats by hard work and talent, as I fervently hope is true, or chemistry.

That's a problem. Because that little voice, if we can't figure out a way to shut it up, could kill the Olympics.

Shares