Will President Bush this week once again put Social Security privatization -- or something close to it -- into the headlines? Maybe he will; maybe he won't. But one doesn't have to read tea leaves to know it's on his agenda.

The ground has been carefully prepared. New books by Peter G. Peterson -- the relentless Cassandra whose Thirty Years' War against Social Security can wear down skepticism even at Salon -- and by Laurence Kotlikoff and Scott Burns are softening up opinion leaders. (See my not-very-favorable review in the Texas Observer.)

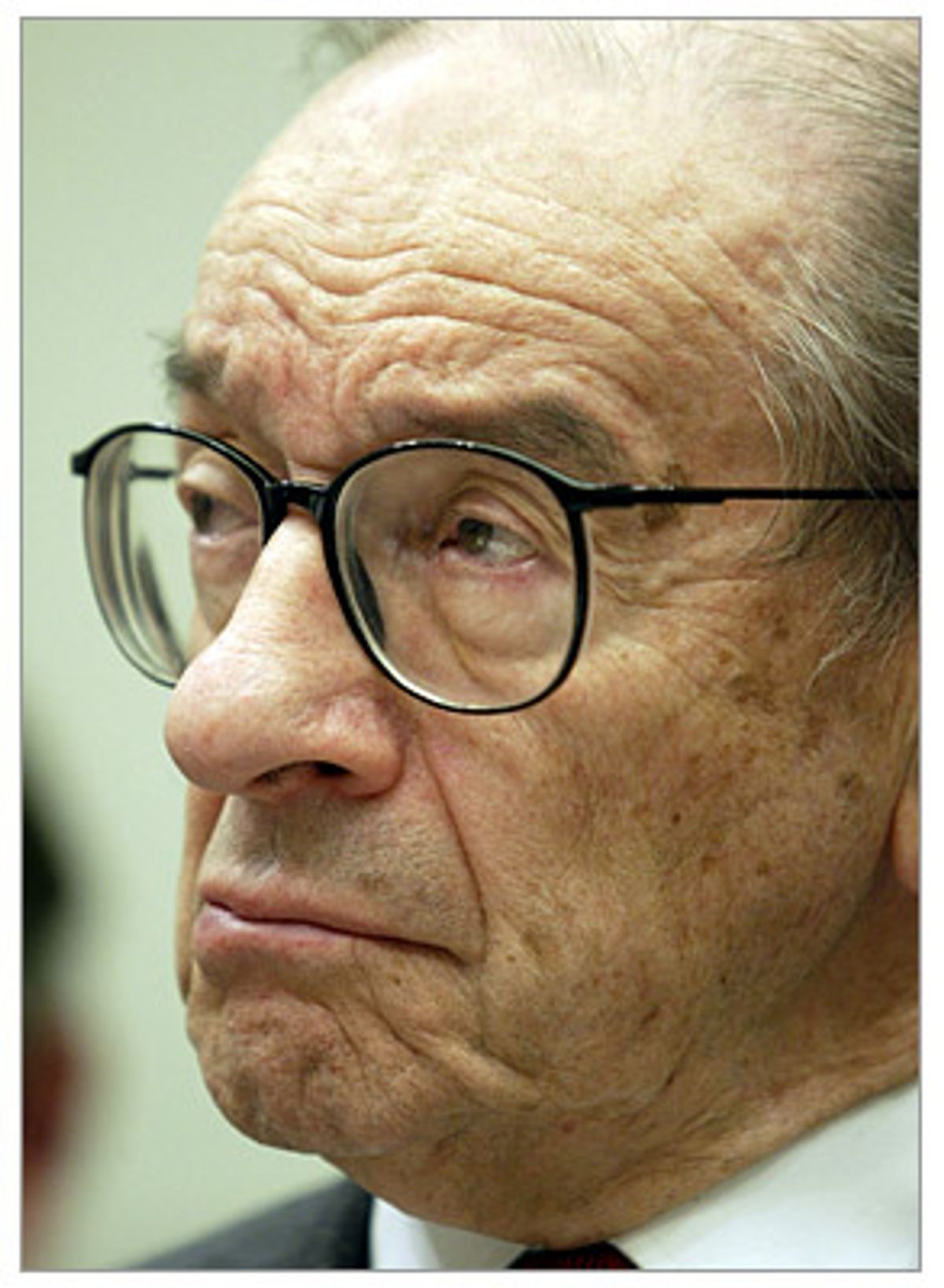

More important, Alan Greenspan is again neglecting his day job to lend respectability to a scare campaign. Speaking at the annual Federal Reserve retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyo., last weekend, Greenspan noted the "abrupt and painful" changes required to both Social Security and Medicare, arguing that the 77 million baby boomers set to retire will simply pose too great a burden otherwise.

Greenspan said, "If we have promised more than our economy has the ability to deliver, as I fear we may have, we must recalibrate our public programs so that pending retirees have time to adjust through other channels."

Friends and readers, look carefully at that sentence, and stop to think about it. First there is the conditional: "If we have promised more than our economy has the ability to deliver ..."

What have we promised? A life of luxury and decadence? That is not the case. Social Security offers a life of modest comfort to most -- not all -- elderly Americans, as well as a system of support for survivors and the disabled. Medicare offers the elderly access to decent medical care. That is all.

Can this truly be more than "our economy" has the ability to deliver?

Greenspan's position is that we as a country -- as an economy -- cannot physically afford to keep our growing elderly population out of poverty. It is that "we" cannot afford to let "them" see doctors when they are sick. Leaving aside the weasel words "as I fear we may have," that is what the man said. He did not say that "the government" can't afford to do this. He said that "the economy" can't afford it.

Mercifully, that is not true. In fact, it is complete nonsense. We are a rich country, and we can certainly find the food, the modest housing, the clothing and the doctors, nurses, and health aides required to keep our elderly out of poverty in the years ahead.

The only question is, do we want to do this or not?

Social Security and Medicare are not mainly about transferring resources from the young to the old. They are mainly about who among the elderly -- and who among the sick and the disabled and young survivors -- gets taken care of, and by whom. It is an issue of distribution and almost nothing else.

What does Greenspan think will happen to the 77 million baby boomers if Social Security and Medicare are scaled back? Does he think we will disappear? Well, we won't. We'll be around for a while. And those of us who have children will be a burden on them -- as our parents are for the most part not a burden on us, because they have Social Security and Medicare. Because they have it, we also have it. If we lose it, our children will pay not only for their own retirements but also for ours. You cannot imagine the cruelty of family life that is coming, in the day when Social Security and Medicare no longer take care of the old.

And what of the elderly who don't have children? Or those whose children are poor? Or those whose children have their own medical problems? Or those whose children just won't pony up? Social Security and Medicare take care of those elderly now, based on their histories of work. Under Greenspan's plan, they would be victims of a lottery based on fertility, psychology, sexual preference and family luck.

Now, there is one other way one might interpret Greenspan's conditional. If it were true that Social Security and Medicare are especially costly ways of providing retirement income and medical care, then he might be right. Perhaps "the economy" really couldn't afford that.

But that isn't true, either. First, compared with private insurance, Social Security and Medicare are bargains. The administrative costs are tiny. Since the government covers everybody, it spends nothing trying to decide who is insurable and who is not. And second, the administrators of these programs are civil servants. They don't have to be paid like private CEOs. If you put everybody in the country on Medicare, private health insurance would disappear and overall medical care would cost less -- with no decline in the quality of service.

Will it be necessary to raise taxes to pay for Social Security and Medicare as they are? For Social Security, the true answer is: We don't know yet. It's quite possible we won't need to raise taxes by a dime. Whether we will or won't will depend on the growth rate of the economy over the next 20 years. If we do have to raise taxes, it won't be by much. And the burden needn't fall on working people, either. There is no reason, in principle or in practice, why we couldn't (for instance) preserve the estate tax and credit its revenues to the Social Security Trust Fund.

For Medicare, yes, existing payroll tax revenues do not cover future projected expenses. But they were never supposed to. Medicare is designed to be funded, in part, by general revenues. It's designed to be paid for, partly, by taxes on income, profits and wealth. Though one can hope for reform that would lower the cost of healthcare, there is nothing wrong with paying for it that way. And Medicare won't be bankrupt until the whole federal government is bankrupt. Which it is not. But even if the whole government were bankrupt, it would make more sense to blame that calamity on Bush's tax cuts or the cost of missile defense, rather than on Medicare. After all, medical care for the elderly is essential. The tax cuts and missile defense were, and remain, unnecessary.

Let me say it again. If we have a financial problem in our government, the fault lies with tax and spending decisions taken by this government in 2001. It is grossly irresponsible, and recklessly cruel, to blame the two programs most responsible for the basic comforts of America's seniors, now and in the years to come.

Now suppose, just for the sake of argument, that Greenspan's conditional were true. Suppose that "our economy" really cannot afford sustenance and doctors for the old. Then, consider the second half of the quoted sentence, in which Greenspan declares that we must "recalibrate our public programs" -- Social Security and Medicare -- "so that pending retirees have time to adjust through other channels."

What other channels exist? If the government cuts Social Security benefits, what will the pending retirees do? Will they save more? In the first place, they mostly can't do that. Most Americans live hand-to-mouth, and if they do manage to save something at one point or another in their lives, they usually lose it to a medical disaster or some other life emergency long before they retire. That is why 65 percent of American retirees live mainly on Social Security right now.

In the second place, saving is an alternative to spending. If American working families really did try to save more, as scolds like Peterson are forever recommending, that would wreck our main motor of economic growth. Note the Associated Press story of Aug. 30 on July's modest "splurge" by consumers. The AP called it "a hopeful sign the economy may be emerging from a summer funk." It would be nice if that were true -- and bad news if, as I suspect, it isn't. Greenspan's idea is to make unavoidable and perpetual the bad news.

But in the third place, even if we who will one day retire could, as a class, save more and provide privately for our own retirements, that would still be an economic channel. Whether financed by public programs or private savings, the resources required to supply modest comfort and medical care are exactly the same. If "the economy" can't deliver one, it can't deliver the other.

Of noneconomic channels, I can think of only three: Prayer. Suffering. And death. What exact combination of these Greenspan prefers, he did not make clear at Jackson Hole.

Shares