William Thackeray once protested that Victorian novelists like him were not permitted to write with the candor that Henry Fielding had enjoyed in the 18th century. But in "Vanity Fair" Thackeray turned the imposed discretion of his age to killing advantage. "Vanity Fair" must be the most decorous savage novel ever written, and it's one of a handful of novels that can be said to describe a complete vision of the world.

The "world" in "Vanity Fair" is England in the years around Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo; Thackeray's portrait of human nature isn't limited to any time or place. Reading the novel, you feel that Thackeray got into it everything he ever witnessed or suspected about human motives. It's a profoundly skeptical book. Thackeray pits worldliness against goodness with no illusions about which quality usually triumphs. Put it this way: In a Dickens novel, a small boy rescued from the torments of a bully will almost certainly grow up to be an exemplar of kindness and gentleness. The same boy, in Thackeray, grows up to be a snob and a rotter and hateful to the friend who saved him from the bully. Multiply those incidents into a panorama that stretches nearly the entire height of early 19th century English society, and are embodied in Thackeray's protagonist, the scheming, status-seeking Becky Sharp, and you have an overwhelmingly coherent and devastating satiric vision.

There may be filmmakers whose own vision is vast enough to take on Thackeray's, but Mira Nair isn't one of them. Her new film of "Vanity Fair" is a disaster. Scene by scene and moment to moment, it's a woeful misreading of the book. To see what's wrong with the movie you need only compare the tag line used in some of the ads -- "On Sept. 1, a heroine will rise" -- with the subtitle Thackeray gave his book: "A Novel Without a Hero."

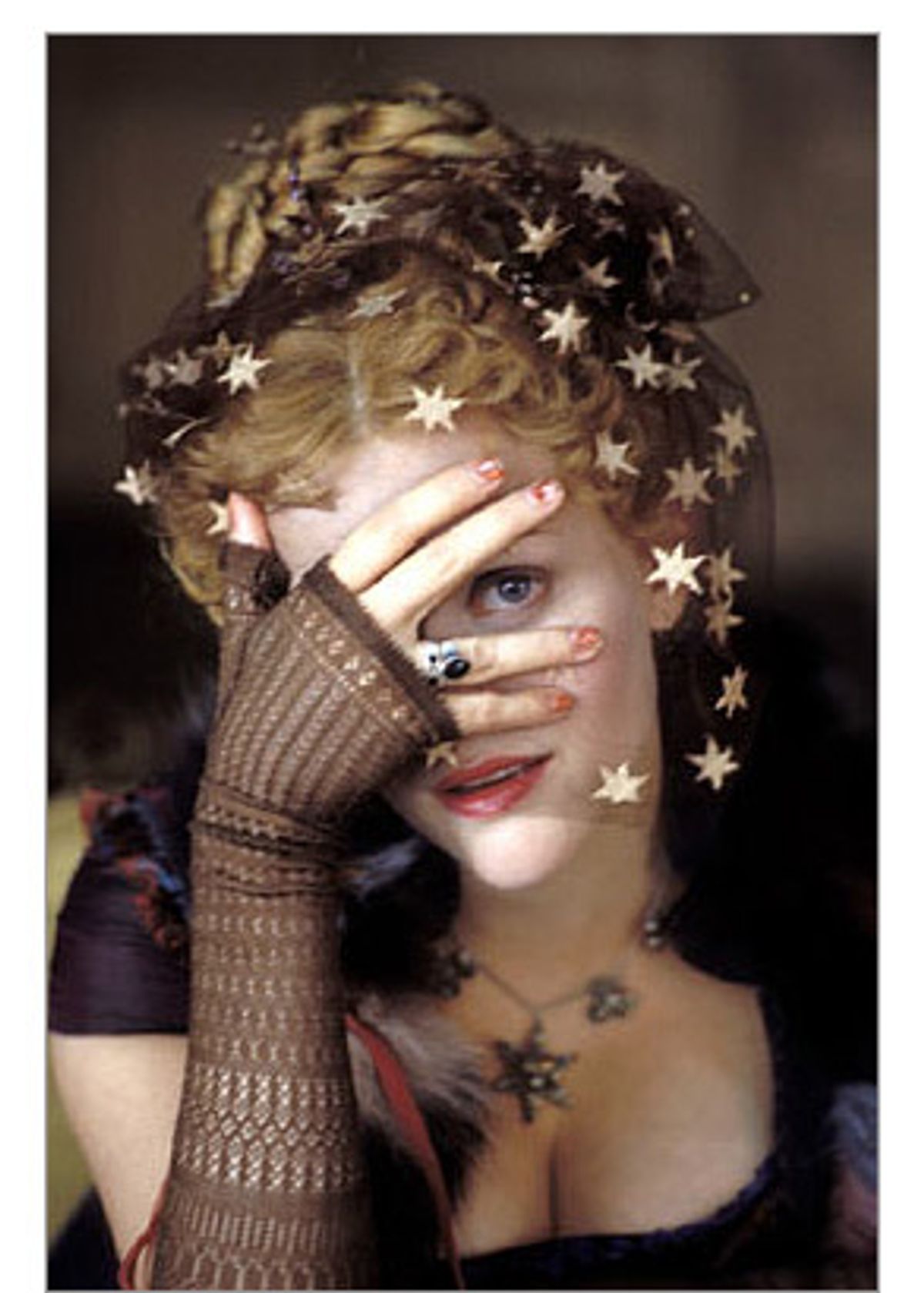

Nair's version is something like a revue version of "Gone With the Wind." Becky Sharp (Reese Witherspoon), the scrappy orphan who works her way up from governess to member of the bourgeoisie, is the heroine here -- the spiritual sister to Scarlett O'Hara, Lorelei Lee and Madonna. She's the movie's Material Maiden, the bitch we're meant to root for. Nair presents Becky's barely disguised avarice and ambition as rebellion against the class-ridden hypocrisy of English society. Witherspoon is quoted in the movie's production notes as saying, "In my opinion, Becky Sharp is an early feminist ... she'd been deprived of parents and has no place to go in the world -- yet she still manages to succeed. Every success she has in her life is based on her own merit, which is a modern idea for a period story."

Compare that with what Thackeray writes about Becky: "Miss Rebecca Sharp has twice had occasion to thank Heaven ... in the first place, for ridding her of some person whom she hated, and secondly, for enabling her to bring her enemies to some sort of perplexity or confusion ... Miss Rebecca Sharp was not, then, in the least kind or placable. All the world used her ill, said this young misanthropist, and we may be pretty certain that persons whom all the world treats ill, deserve entirely the treatment they get."

It's not that Becky's plotting isn't often very amusing. The problem is that Nair and her screenwriters (the team of Matthew Faulk and Mark Skeet, and "Gosford Park" screenwriter Julian Fellowes) have taken Thackeray's amusement at Becky to mean that he isn't also appalled by her. So we get scenes that, even when they follow the events of the book, completely rewrite its meanings. When Becky's husband Rawdon (James Purefoy) goes off to fight Napoleon, we see him bidding loving goodbye to his tearful, pregnant wife. Thackeray tells us that Becky was "wisely determined not to give way to unavailing sentimentality on her husband's departure." She waves goodbye from a window, takes off her ball gown, smiles at the note she has secreted from her best friend's husband begging an assignation, "and slept very comfortably."

The filmmakers don't go soft on just Becky -- they take the same tack with Thackeray's virtuous characters who, good though they are, tend to be simps. Becky's best friend, Amelia Sedley, is, we are told, possessed of so much sensibility that she weeps when her pet cat brings her a dead mouse. In Nair's "Gone With the Wind" scheme, she's the movie's Melanie. Romola Garai is a very appealing young actress, but there's not much she can do with the one-note conception. And though Rhys Ifans, as William Dobbin, the officer secretly in love with Amelia, rightly has something of the galoot in him, he's neither sympathetic enough nor satirized enough to make much of an impression. God only knows what impression we're to take from Jonathan Rhys-Meyers as Amelia's husband, George Osborne. The character is a philandering, spendthrift cad. For some reason, Rhys-Meyers has chosen to play him in the mincing closet-queen style of a George Sanders villain.

Some of the cast manage to do good caricature work, like Geraldine McEwan, and especially Eileen Atkins as Becky's vinegary old benefactor. I don't think I've ever liked Atkins as much as the moment here where she removes her elaborate headpiece and scratches her wiry gray hair with palpable relief. (It's also amusing that Atkins' long face looks like a cartoon version of Jean Cocteau.)

How is Reese Witherspoon? Fine and all wrong. Her English accent is fine -- if that's your idea of what acting consists of. And she has the comic moments you'd expect where you can see the wheels turning as she schemes how to get ahead. But does anyone look at that snub nose and see anything other than an American girl playing dress-up? And there's a further problem. It's possible that Witherspoon merely found herself caught here in a director's misconception. But if the tales of the control Witherspoon has exerted on her projects -- and her own statements in support of Nair's conception -- are to be believed, then she has to share the blame. And I fear that after getting a taste of what it's like to be adored by the public in movies like "Legally Blonde" and "Sweet Home Alabama," Witherspoon may be reluctant to throw herself into a true depiction of a character as plainly mean as Becky Sharp. The Witherspoon of "Freeway" and "Twilight" and "Pleasantville" wouldn't have shied from Becky's coldness. The aspirant to the title of America's Sweetheart engages in a snipe hunt for Becky's heart.

To be fair, a film of "Vanity Fair" would be a challenge to filmmakers far more talented than Nair. Thackeray's voice holds together his panoramic structure. Deprived of that voice, the story flits from scene to scene. Part of the problem may simply be the movie's compressed time scheme. Trying to telescope "Vanity Fair" (my Modern Library edition from the '50s runs 730 pages) into 136 minutes is an inhuman task.

But "Vanity Fair" often seems as if no one involved with it has actually read the novel. My hunch is that someone involved with the production decided that Thackeray was a dead white male whose vision needed to be "expanded" -- and I'm betting it was Nair. Part of the reason for the film's depiction of Becky as a heroine is that the society she is infiltrating is a colonial power in India. Thackeray was actually born in India and one of his characters, Jos Sedley, has made his fortune there. In Nair's vision, the English passion for all things Indian is translated into ludicrous scenes like a Sunday outing where sitars play, fire acrobats perform and tattooed women belly-dance -- in public? In early 19th century England? Even sillier is a scene where Becky takes part in parlor theatricals in which the women baring their midriffs are the respectable wives and daughters of the well-heeled, whom we have seen snubbing Becky as an intemperate jade a few scenes before. What is this Bollywood fantasy doing in the midst of "Vanity Fair"? Why, when we are meant to be in the 1800s, are we watching women writhe to what sounds like a dance remix of some bhangra hit?

It's not that directors shouldn't be free to reimagine and reinterpret. But when directors substitute their vision for that of a great artist, they run the risk of being found wanting. Thackeray, writing in 1843-44, was simply not dealing with either feminism or imperialism. Could Nair have addressed them? Yes. But the way she has chosen to do so violates the dramatic reality of the time she is working in.

A director's desire for a work to be something other than what it is doesn't just occur in bad movies -- I love Kenneth Branagh's film of "Henry V," but no matter how much he wishes it, Shakespeare did not write an antiwar play. But that film was the work of a loving upstart, a first-time director setting himself a wildly ambitious task. And it was marked by Branagh's belief that Shakespeare's vision was big enough to support his reading. Nair's vision of Thackeray has the corrective tone of a prissy schoolmarm. She has missed the universals in Thackeray because she is hung up on what's left out of his specifics. Her vanity here would fit snugly into the book. By the end of the movie, her vision seems no bigger than a speck. In setting herself against Thackeray, Nair becomes the Incredible Shrinking Director.

Shares