I took a poetry class in New York in the spring of 1996, frankly, to meet women. The desks looped around the room in a U-shape. Scanning the students, most of whom were male, I noticed a Jeff Buckley look-alike and made a mental note to tell him about his resemblance.

I was a huge fan of Buckley's, whose 1994 breakthrough album, "Grace," has just been rereleased ("Grace: Legacy Edition") in expanded form by Columbia Records in honor of its 10th anniversary. The original release of "Grace" in August 1994 earned Buckley, then 28, critical raves and a devout cult following that's only grown over time. It was the only full-length album Buckley put out in his lifetime, and sitting there in that classroom, I knew every note of it by heart. A few months after its release, I'd seen him perform at Irving Plaza. As his voice flowed from grainy, guttural tones to sultry softness midnote, I felt like the character from "Bhagavad Gita" who is humbled to his core upon seeing the vastness of the lord's form.

A young guy sitting to my left passed an alphabetized sign-in sheet to me. Jeff Buckley's name was listed directly above mine, with his looping signature next to it. My heart started trying to leap through my chest. I took slow, deep breaths as the teacher introduced herself. Listen, I told myself. You know what happens in classes like this: Everyone gets to know each other really well. Do not blow it. Just get to know him naturally.

The next hour was a blur. At the break, students drifted into the hallway leaving behind their stuff, casually strolling past Buckley, appearing to have no clue who he was.

Jeff and I were the only ones left in the room. I looked at him from my seat. He wore a white, V-neck T-shirt and sat slouched in his chair, gazing out the window. "I'm a very big fan of yours!" He sat up. "Thanks," he said. "Have you been to any of the shows?"

I wanted to explain how moved I was by his performance, by him, without embarrassing myself -- an impossible task, so I withheld the description of what that night meant to me. "I saw you at Irving Plaza a few years ago ... great show."

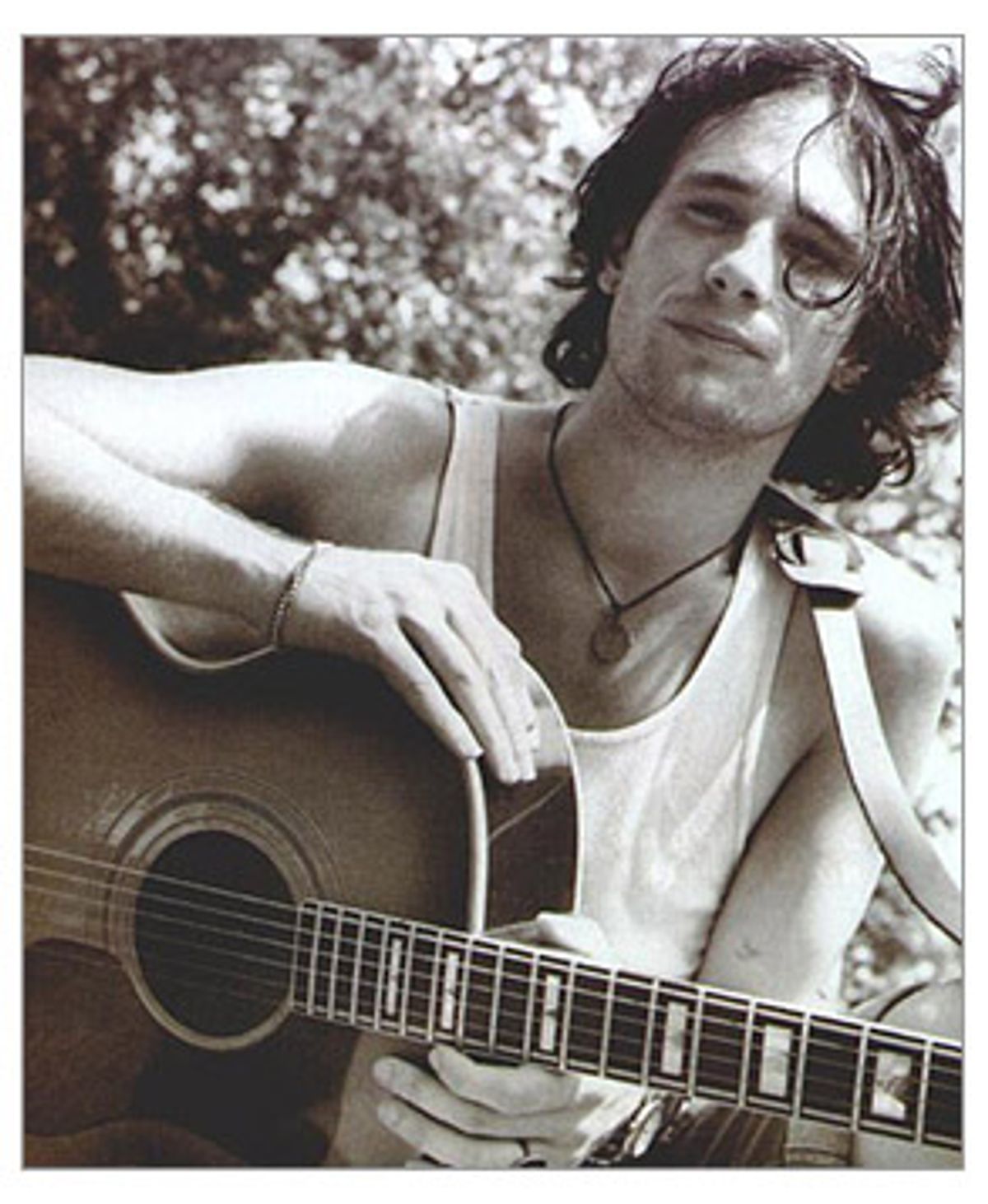

I avoided him over the next few weeks, choosing instead to observe him furtively. My notes from the second class include: "Greasy hair." "Exquisitely shy. How could this be the guy I saw in concert?" "Feminine, high-pitched voice." "Delicate, almost apologetic laugh." "Trance-like countenance." "Pale."

As class ended that day, the teacher announced that I was to bring in photocopies of an original poem the next week, so everyone could take it home and prepare to discuss it.

Filled with anxiety, I wrote prolifically over the next six days and, of course, liked none of my work. When my poem was discussed and it was Jeff's turn to comment, he said he liked a line about handing a Walkman to a bum. "And your suggestion for improvement?" the teacher, who insisted that we provide a positive and a negative remark, asked him. He turned to me with a half-smile and dispensed some mild, meaningless criticism about "tightening a few of the lines."

Jeff passed out photocopies of his poem, titled "Fullerton Road Trick," about a childhood prank of playing dead by the side of the road, as class was ending. I placed it in my bag casually, hiding my terror that it might wrinkle. I walked to a coffee shop. His poem was written by hand, a handwriting I would recognize when bits of his journals were included in the liner notes to his next album, which he would never complete. It's a poem that honors a childhood innocence, free from any fear of mortality ("I've felt this season before/ As a child playing dead near the road/ One curious blankfaced summer/ Unaware that the flesh will erode"). The last line is: "We burst back home through the nowhere to sleep in the season of summer destruction." He would drown in the Mississippi the next summer in Memphis, a death that paralleled that of the father he met just once, the '60s singer-songwriter Tim Buckley, who died of a heroin overdose in 1975 at age 28.

We reviewed his poem the next week. The rule was that the poet would read first, and then another student would give it a second reading. Jeff read like he spoke -- in slow contemplation, then bursts of luminous words.

"Thank you, Jeff," the teacher said, leaning back against the blackboard. "Let's have another reading." I was staring straight into the blank whiteness of the top of my desk. The room was silent. "Scott. Would you like to read?" My nerves, combined with the small stems on his Y's, caused me to read "tryst" as "trust" in the line "we the jagged dishonest music produced by desperate tryst and divorce."

He walked up to me as our classmates left. "Hey, Scott." He stuffed his hands into the front pockets of his jeans. "I'm playing Sin-é Monday night, unbilled, so I thought you might like to come."

He never showed up to that gig or in class again, and a couple of weeks later, the teacher announced that Jeff had called her to say he'd had to drop the class.

"Apparently he is a musician and he has moved to Memphis to work on his next album," she said. "He asked me to wish you all good luck."

Shares