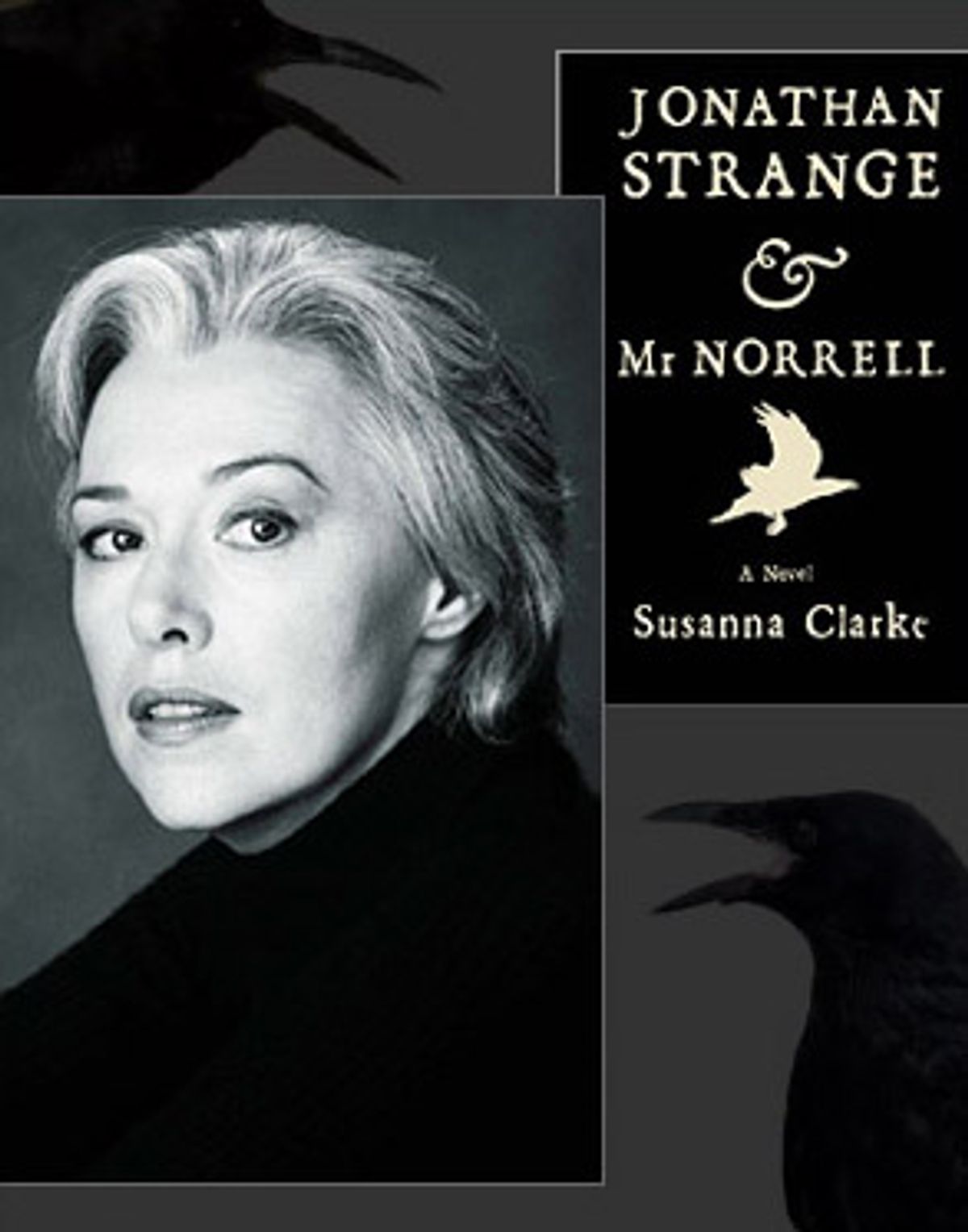

It may be just as well that Susanna Clarke's first novel, "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell," is nearly as big as a house, since this is the kind of book you want to move into and settle down in for a long stay. It's set in a world very much like the England of the early 1800s, only in Clarke's version magic was once a daily presence and has since been lost or perhaps merely misplaced. In other words, this world resembles the world of our own reading, for most of us can remember a time when stepping into a book was like entering into an enchantment.

Even if, as adults, we have learned to read differently and to appreciate other books that don't necessarily cast the same spell, most of us continue to yearn for that magic and to cherish the rare book that can still work it. We may admire those other, possibly greater books, but the ones that enchant us -- "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" is destined to join that company -- are the books we love. Some people might call this regressive, and perhaps it is. But the nature of love is to be regressive and irrational and irresponsible, and life without it would be a drab thing indeed.

The England of "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" has drifted away from its magical past and lingers on the momentous cusp between the intellectual splendors of Enlightenment reason and the nitty-gritty convulsions of industrialization. All of English fantasy is an argument between the wild and the civilized, but Clarke takes an unconventional position by seeing value in each. Although "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" is about magic -- specifically about the two eponymous magicians, who seek to return English magic to its former glory -- it is also about a certain literary voice, the eminently civilized voice of early 19th century social comedy. That voice reached its pinnacle in Jane Austen and, for all its reason, its common sense and skeptical wit, it works its own brand of sorcery. It seems impossible to combine two such contradictory literary delights, but Clarke does it with ease.

The plot of the novel is simple enough. Mr. Norrell, a formerly reclusive, book-hoarding scholar, emerges on the London scene as something previously considered extinct: a "practical" magician. ("Theoretical" magicians, men who study the magic of the Middle Ages but wouldn't dream of attempting it, are much more common.) His unprepossessing appearance notwithstanding, "within Mr. Norrell's dry little heart there was [a] lively ambition to bring back magic to England." He can't tolerate the idea of a potential rival, however, so he devotes most of his time to squelching everyone else's aspirations in that department.

Until, that is, he meets Jonathan Strange, a rich young gentleman of undeniable talent, who offers himself as Norrell's pupil and a more socially polished representative of "modern magic." They make an excellent team. Norrell prefers to hole up in his library, while Strange is much better suited to a key element of Norrell's campaign: using magic to assist the stalled British war effort against Napoleon. Britain's ministers send the intrepid Strange off to Portugal, where he enjoys a series of thrilling adventures under the command of the Duke of Wellington.

The collaboration eventually hits the rocks when Strange grows restless and preoccupied with the Raven King, a shadowy figure who ruled Northern England from 1111 to 1434. According to Mr. Norrell, the Raven King embodies everything primitive, unruly and dangerous about their art; he must be repudiated if magic is to become truly useful and, most important of all, respectable. The King, Strange counters, "stands at the very heart of English magic, and we ignore him at our peril." Strange's pursuit of the Raven King brings him dangerously close to a secret, a secret that concerns the feat of magic that brought Mr. Norrell into the confidence of the nation's most powerful men.

Although it becomes urgent toward the novel's end, initially the pace is leisurely, as Clarke wanders through a series of anecdotes and small scenes, all liberally embellished with footnotes and asides and all of it almost ridiculously witty, imaginative and diverting. Clarke has invented an extensive history of English magic, complete with dozens of rare and learned texts, common misperceptions and even disappointments. "Like many spells with unusual names," one footnote informs us, "the Unrobed Ladies was a great deal less exciting than it sounded. The ladies in the title were only a kind of woodland flower."

Spells themselves are relatively scarce in the opening chapters. Clarke devotes more of her novel's first pages to sharp and sparkling descriptions of Strange and Norrell's social world and the people who inhabit it. All of this is seamlessly woven into real history and the lives of actual people. Of an important man who will prove essential to Norrell's plans, she writes:

"Sir Walter Pole was 42 and, I'm sorry to say, quite as clever as any one else in the Cabinet. He had quarreled with most of the great politicians of the age at one time or another and once, when they were both very drunk, had been struck over the head with a bottle of Madeira by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Afterwards Sheridan remarked to the Duke of York, 'Pole accepted my apologies in a handsome, gentleman-like fashion. Happily, he is such a plain man that one scar more or less can make no significant difference' ...

"Some years ago his friends in the Government had got him the position of Secretary-in-Ordinary to The Office of Supplication, for which he received a special hat, a small piece of ivory and seven hundred pounds a year. There were no duties attached to the place because no one could remember what The Office of Supplication was supposed to do or what the small piece of ivory was for."

The unflappable authority and precision of this voice, the detail that the bottle contained Madeira, the duke's clubby quip preserved for the ages, the feudal curiosity of the Office of Supplication -- this perfectly reproduces the tone of a classic work of British history or biography, and that alone is amusing. But Clarke is particularly droll when she applies the judicious manner of the historian to the stuff of fairy tales. A footnote relating a story about a magic ring describes what happens when the ring is absent-mindedly set down next to three eggs. From one egg hatches "a stringed instrument like a viola, except that it had little arms and legs and played sweet music upon itself with a tiny bow." From another comes "a ship of purest ivory with sails of fine white linen and a set of silvery oars," and from the last "a chick with strange red and gold plumage." The first two marvels soon vanish, "but the bird grew up and later started a fire that destroyed most of Grantham. During the conflagration it was observed bathing itself in the flames. From this circumstance, it was presumed to be a phoenix."

"Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" brims with minor characters whose vivacity recalls the great caricatures of Dickens, from unctuous social climbers and dithering aristocrats to supercilious rakes and the formidable Duke of Wellington. Upon being informed that several Neapolitan corpses reanimated by Strange are speaking "one of the dialects of Hell," the Duke remarks, "'They have learned it very quickly ... They have only been dead three days.' He approved of people doing things promptly and in a businesslike fashion."

Into this very dry and delicious form of British comic writing Clarke injects her scenes of magic, a powerful, uncanny imagery that's very English, too, in its own way -- think of the intoxicating brambles of Shakespeare's "Midsummer Night's Dream." Mr. Norrell's first spell, a kind of exposition intended to cow his competitors, causes all the statues in the Cathedral at York to move and speak, a frightening racket of gravelly voices and grinding stones in which one small carving cries out over and over again about the murder of a young woman "with ivy leaves in her hair" for which it was the only witness. Later, Norrell idles a French naval squadron by blocking the mouth of a harbor with a fleet of British warships made entirely of rain. Other, briefer images seem delivered from the golden age of surrealist film: A little girl wanders into a room that "contained nothing but a high mirror. Room and mirror seemed to have quarreled at some time for the mirror showed the room to be filled with birds but the room was empty."

Occasionally the magic in "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" is as merry as a story told to children. A captured French ship features yet another carving that can be commanded by magic to speak: "a very fine figurehead in the shape of a mermaid with bright blue eyes, coral-pink lips, a great mass of sumptuous golden curls artistically strewn with wooden representations of starfish and crabs, and a tail that was covered all over with silver-gilt as if it might be made of gingerbread ... She could not at first be brought to answer any questions. She considered herself the implacable enemy of the British and was highly delighted to be given powers of speech so that she could express her hatred of them. Having passed all her existence among sailors, she knew a great many insults and bestowed them very readily on anyone who came near her in a voice that sounded like the creaking of masts and timbers in a high wind."

This exasperates her interrogator, who threatens to have the mermaid chopped up for a bonfire, "But, though French, she was also very brave and said she would like to see the man that would try to burn her. And she lashed her tail and waved her arms menacingly; and all the wooden starfish and crabs in her hair bristled."

Most of the magic in "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell," however, is more wintry and sinister -- flocks of black birds, a forest that grows up in the canals of Venice, a countryside of bleak moors that can only be entered through mirrors, a phantom bell that makes people think of everything they have ever lost, a midnight darkness that follows an accursed man everywhere he goes. It is often the work of fairies, who in this novel are not tiny darling winged sprites, but full-size people with foxlike faces and a host of bad qualities: capriciousness, indolence, malice, vanity and a habit of kidnapping mortal men and women and carrying them off to the Otherlands, their home, for an endless round of tiresome processions and balls.

For Mr. Norrell, who wants to make magic a kind of genteel science in keeping with the tenor of his times, dealing with such entities is unthinkable. But if the Augustan spirit of Jane Austen and Samuel Johnson, with its vigorous common sense, its firm ethical fiber and its serene reason and self-confidence is fundamental to Englishness, then so, too, is the muddy, bloody, instinctual spirit of the fairies, and an England that forgets this is a nation not only less powerful, but one exiled from itself. Since one of the things "Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell" is about is what it means to be English (and not without digs at the arrogance, provincialism and class prejudice that goes along with it), the promise of a closing of this long-standing divide is most welcome. The novel itself achieves it, and in the consummation transcends anything as parochial as national character. Susanna Clarke's magic is universal.

Shares