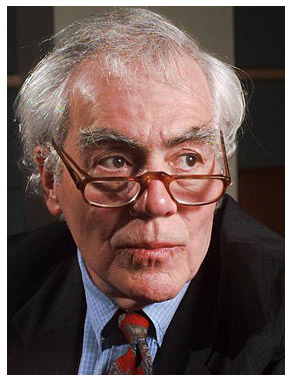

Jimmy Breslin wants to start his own church. He’s had enough of the old one after almost 74 years, and who can blame him?

When you look back over the career of New York’s consummate common-man columnist — one of the best at cramming characters, emotion and sense of place into a 650-word rectangle of newsprint that Gotham has ever seen — his break with the Roman Catholic Church has been a long time coming. It wasn’t exactly the sexual abuse scandal itself that sent Breslin over the edge, although he’s been covering it with intense and deepening anger for the last two years. Instead, he says, it was one of the scandal’s side effects: discovering that one of the American church’s most prominent men of God was a niggling, pedantic little man.

“A couple of things did it,” Breslin tells me in his gargling-with-glass Queens accent. “I think, most of all, it was reading the transcripts of Cardinal Egan, when he was the bishop up in Bridgeport [Conn.], quibbling over the classification of a young man who was abused.” That would be Cardinal Edward Egan, who was appointed archbishop of New York, and hence de facto leader of the American church, despite his indirect implication in an especially seamy scandal at his former diocese in Connecticut.

“They were in court over the issue of — did the priest bite his penis or did the kid bite the priest’s penis? It was confusing,” Breslin says drily. Egan objected to the opposing attorney’s reference to the young man in the case as a child, since he had been a college freshman at the time. “He was testifying, Egan, and he wondered whether they should call this kid a child or a young man, because he was a student at Sacred Heart College. Basically, he was quibbling over the classification of a young man who was involved in a sexual act with a priest.”

When you sit and talk with him, Breslin is a rumpled but guarded presence; like so many reporters, he keeps his own counsel. But here he sits up straight in his chair and spreads his hands wide, in a classic pose of street-corner argumentation. “Well, come on!” he says. “What are you, a cheap defense lawyer in Queens Criminal Court? Or what are you? Are you a church leader? Someone who can rise above this? No!”

Later in the same testimony, Egan went even further. He proposed the novel idea that bishops and other figures in the church hierarchy could not be held responsible for crimes committed by priests, because priests were private contractors rather than employees. To even the most firmly lapsed of ex-Catholics, this was a shocker: The men uniquely entrusted with the role of mediating between God and man, uniquely empowered to transform a translucent cracker into the flesh of Our Savior, had the same legal status, according to the archbishop, as traveling encyclopedia salesmen. “That was enraging,” Breslin says, now quiet again. “Such an outright, blatant lie.”

I visit Breslin on a brilliant summer morning at his apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to talk about the eccentric and highly personal new book that marks his farewell to Catholicism, “The Church That Forgot Christ.” The housekeeper lets me in; Breslin isn’t there. He arrives a few minutes later, damp from a morning swim and a shower, still wearing a robe and flip-flops, and offers me coffee. He lives with his wife, former New York City Council member Ronnie Eldridge, in one of those brand new luxury penthouse apartments that looks like a furnished suite at the airport Hilton. At first it seems like a funny place to encounter the quintessential voice of the outer-borough working class. But as a friend of mine observed later, it’s exactly the kind of digs the outer-borough working class would live in if they could afford to.

Breslin doesn’t seem like an angry man in person, but “The Church That Forgot Christ” is fueled by unquenchable bitterness and rage against the church that reared him and the vanished world of Irish Catholic Queens that fed it. He was brought up as a “stone Diocese of Brooklyn Catholic,” as he puts it, and attended weekly mass for virtually his entire life. For most of that time, as a troublemaking, thumb-in-the-eye-of-power columnist for four different newspapers (the last 12 years for Newsday), he has served as New York’s — and maybe America’s — most vocal lay representative of the church’s liberal, Vatican II wing. He is a social-justice Catholic, a civil rights Catholic, an anti-death penalty Catholic, a feminist Catholic, a gay rights Catholic. Once upon a time, those didn’t seem like impossible or self-contradictory categories.

At his age, Breslin isn’t the reporter he used to be, as he’ll admit to anyone. But he retains one of the finest sets of eyes and ears in the news business, along with a unique ability to penetrate the absurdity and flat-out bullshit of so much public discourse, and his trademark staccato writing style. In the huge Aug. 29 march, when 500,000 people came out to the streets of New York to stand against George W. Bush, Breslin walked next to a college student carrying a cardboard casket as they passed a commemorative sign marking East 20th Street as Theodore Roosevelt Way:

“Of course something had to put that sign there and have it noticed on this day. For it was Roosevelt who in the end seems to have known so much and so many of the governments that followed so little.

“And here, as Sarah Kruger passed under the street sign, were the words Roosevelt thought should be commonplace in his country:

“‘To announce that there should be no criticism of the president, or that we are to stand by the president, right or wrong, it is not only unpatriotic and servile, but it is morally treasonable to the American people.’

“And you could hear in the air his cry for lovely young Sarah Kruger: as she passed under his name carrying a casket: ‘Bully!'”

I mention to Breslin that this article is likely to run on the anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, assuming that this consummate New Yorker will have something to say about that momentous event in the city’s history. “I try not to pay attention to it,” he says. “The anniversary is a day for exhibitionists, and for politicians trying to use it to their advantage. Who tried to use it more than Giuliani, the dog?” He uses another word, a gerund adjective, right before “dog.”

“What would you want to be around it for? People I know don’t care about it. I know the widow of a firefighter, and she doesn’t want to hear anything about it. For me, the important anniversary came on the first Monday after the attacks, when everybody got up and went to work [after a week when the city was essentially closed down]. If their jobs were in Jersey City now, instead of lower Manhattan, then they got on the train and went to Jersey City.”

In a recent column, Breslin observed that Osama bin Laden must need a new press agent, since no speaker at the Republican Convention was even willing to utter his name. “Well, one fellow mentioned it, he slipped up,” he says. “It was [New York governor] George Pataki. And he had to make recompense with a scathing attack on Saddam Hussein, like he had anything to do with it.”

Returning to the subject of Catholicism, I suggest to Breslin that from my limited perspective, as an “ethnic” Catholic whose ties to the church are those of blood and heritage rather than faith, the left-progressive strain of the church doesn’t seem dead yet. He waves me away with a shut-up-already gesture. “There was only one person,” he says. “Pope John XXIII was the only one we ever had, period. There was nothing before or after.”

Maybe that’s not a defensible statement on a factual or logical level, but it’s the kind of emotional, electrical columnist’s shorthand in which Breslin specializes. This is a guy who has done what he calls “the unthinkable” by abandoning the church of his upbringing and his forefathers. He clearly isn’t alone. “The Church That Forgot Christ” is an impressionistic, anecdotal book in a vintage Breslin groove (which you either get or don’t get), but if it can be said to have a central argument, it’s that the current crisis in Catholicism is much wider and cuts much deeper than we now realize.

In his book, Breslin writes, “There have been four great movements in modern America that occurred without the news reporting industry knowing anything about them until they became a part of regular life. The first was civil rights, then the women, and, third, homosexuals and, last and suddenly, the crumbling of the Catholic church.”

The clerical sexual abuse stories may have faded from the front page with the presidential campaign and the war in Iraq, but new cases of almost unbelievable depravity keep surfacing, seemingly by the dozen. The church now says it suspects there are something like 4,000 bad priests and 10,000 cases of abuse in the United States, which by any objective standard is a horrifying number. But Breslin insists that based on his reporting, which by its nature is anecdotal and subjective rather than scientific, he believes that’s only the tip of the iceberg. The true number, he thinks, is 25,000 pedophile priests and something like 100,000 abused children in the years since 1950.

In other words, the Catholic Church in America became, at best, an institutional safe harbor for rapists and child molesters. The vow of celibacy became a cloak worn by warped and damaged men incapable of forming adult emotional attachments, who used their power and privilege to prey on the children entrusted to them by believers. It’s hard to overemphasize how gravely the American church has been wounded by these last few years, or how deeply the church hierarchy, with its endless litany of lies, denials, evasions and weasel words, has been implicated.

The churches of North America are not yet empty, Breslin says. “But they’re gradually emptying out. Collections are down. And it’s not going to reverse. You just get the feeling that young people are staying away.” When I ask him whether he thinks young families, the backbone of any organized religion, are still going to Mass, he stares at me in disbelief. “Would you?” he barks. “If you had younger kids now, would you go? I mean, it’s horrible.” (I do, and no, I wouldn’t.)

Consider the case of Joseph P. Byrns, a priest who made the local news in New York a few weeks ago. Breslin hasn’t written about Byrns, maybe because there’s nothing exceptional about his story. Byrns was a prestigious figure in the universe of New York Catholicism; for many years he presided over a parish in the wealthy neighborhood of Douglaston, Queens, where he married John McEnroe and Tatum O’Neal in the 1970s.

Two years ago, during the dark summer of 2002, when the sexual abuse scandal spread across the continent like an uncontained wildfire, Byrns was caught up in it. He was accused by a fellow priest, a man in his 40s, of having abused him three decades earlier, when the younger man had served as an altar boy in Byrns’ Douglaston parish.

Unlike so many other accused priests and bishops, however, Byrns didn’t cut and run. Instead, he stood up in the pulpit of his current parish, St. Rose of Lima in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Ditmas Park, and “unconditionally” denied the charges, calling one of his accusers “deeply troubled and disturbed” and inviting parishioners to pray for the younger man. The mass-goers at St. Rose gave him a standing ovation. Bishop Thomas Daily, then the boss of the Brooklyn diocese, stuck by his man, insisting the allegations were untrue. One good priest, it seemed, had stood up against the hysteria and paranoia sweeping through the church.

Of course the story didn’t end there. Byrns was quietly suspended from St. Rose after the Queens district attorney announced that the charges against him were credible, but could not be prosecuted because the statute of limitations was long past. Last month, on Aug. 18, state police hauled Byrns out of a Holiday Inn in the upstate town of Oneonta, N.Y., where he was apparently hiding out. The new charge? Byrns is accused of repeatedly fondling and sodomizing an altar boy at St. Rose, during exactly the same period when he was delivering impassioned sermons proclaiming his innocence.

Byrns is still entitled to the presumption of innocence, at least until a Brooklyn jury gets ahold of him. But the Catholic Church isn’t; it exhausted that right a long time ago. The only extraordinary thing about Byrns’ case is that it’s not extraordinary at all: the pattern of incorrigible abuse, the arrogant denials and seemingly pathological lying, the stonewalling and waffling of the hierarchy (which now says it was never sure whether the earlier charges were true), the humiliating comic-opera arrest (when he saw the cops, the 61-year-old cleric tried to skedaddle out the Holiday Inn’s back entrance; they chased him down in the parking lot). The fact that all this was buried deep in the local news — “Perv Priest Nabbed” was the New York Post headline — testifies to how inured we have become to such tales of corruption. Just another priest screwing the altar boys and brazenly lying about it. Geez, what do you expect?

Breslin doesn’t exactly put it this way in his book, but the current scandal seems to represent all the sexual hypocrisy of the Catholic hierarchy, all its misogyny and homophobia, all its cosseting of tyrants and its not-quite-repented anti-Semitism, finally coming to a head. The idea that a religion built around a terror of sex and sexuality was sheltering predatory pedophiles in large numbers seemed too medieval to be believed, too much like the sniggering punch line to an anti-Catholic joke. Breslin reports that in his conversations with other Catholics who ought to have known better, like New York police commissioner Ray Kelly, they all report feeling foolish about how long it took them to understand what was happening.

“It was hard to understand, personally,” Breslin says. “Being raised in Queens like that, I don’t think I knew anybody who wasn’t Catholic. All right, I knew some Jews, maybe a few Protestants. But everything you did was associated with Catholics. If you went to a pro football game, well, that was a Catholic thing.” Still, anyone who belonged to the church (like Breslin) or who felt attached to it by blood and heritage (like me) cannot have been totally surprised when the truth began to come out. “You heard certain stories” about certain priests, he admits. “But I never paid the slightest attention whatsoever.”

Now, with the institution’s credibility shattered and its future in jeopardy, he says there is only one solution. “Those people have to get out of the sex business. Just get out of it. They have no idea what they’re doing.”

There is little chance of that. Conservatives within the church, including some truly frightening reactionary elements who view Pope John Paul II as a softhearted liberal, have seized on the scandal as an opportunity to drive leftists and homosexuals out of the priesthood. They are not just willing but eager to jettison undesirable Catholics like Breslin, who are insufficiently committed to the church’s sexual and moral agenda. They seem to want a smaller, narrower faith obsessed with fighting abortion and gay marriage, rather than a big-tent religion that encompasses family-values conservatives, fervent opponents of the death penalty and Latin American socialists alike.

Some of the saner Catholic prelates, like Cardinal Theodore McCarrick of Washington, D.C., have recently disavowed the wild notion that liberal Catholic politicians who favor gay rights or reproductive choice, from John Kerry to Jim McGreevey, are not entitled to receive communion. But make no mistake, these radical positions are spreading among the true believers; priests in central New York state, where I spend much of the summer, have been handing out bumper stickers to parishioners reading: “You can’t be pro-choice and be a good Catholic.” (No priests that I know of have suggested the corollary position, that you can’t support the death penalty and be a good Catholic.)

Isn’t the church hierarchy, I ask Breslin, now making common cause with its longtime adversaries, the Protestant fundamentalists of the Christian right? “Well, the bishops are more comfortable with them, I think,” he says. “Execution, they say they’re against it.” He makes a growling, throaty noise I take to be laughter. “They’re for it! Why don’t they stop lying? The war in Iraq, they hardly whisper about it. The pope says he spoke out against it. Well, I’m unfamiliar with the stridency of his demands that the war end. I don’t see any social good they do these days.”

If you want a clear and cogently argued discussion of the current crisis in American Catholicism, or a journalistic history of the clerical abuse scandal so far, you’ll want a different book, maybe Garry Wills’ “Why I Am a Catholic” or Frank Bruni and Elinor Burkett’s “Gospel of Shame,” or the riveting “Betrayal: The Crisis in the Catholic Church,” by the staff of the Boston Globe. “The Church That Forgot Christ” is something else, something very much in the Catholic tradition: I’d call it a lamentation.

Most vividly, Breslin’s book offers a quasi-nostalgic tour of his old stomping grounds, amid the semidetached houses of Irish and Italian Queens, from Woodside to South Ozone Park, from Forest Hills to Jackson Heights. It’s a world that has all but disappeared; a generation ago Queens was still the homeland of New York’s “white ethnics,” while today it is one of the most diverse places on the planet. (Elmhurst Hospital reportedly has access to interpreters for more than 150 languages, including Hmong, Albanian, Bengali and Yoruba.)

Breslin recalls many of the people and places of the old Queens tenderly, but he doesn’t exactly miss it. When he returns to the parochial school in Richmond Hill where he was educated and finds that many of its students, and many neighborhood residents, are now Sikh immigrants, he seems positively delighted. “I thought they were great,” he tells me. “I didn’t know anything about their religion, but they told me that they believe men and women are equal, people of all faiths are equal.” In other words, whatever their issues and problems may be, at least they’re not the same old sour Irish Catholics.

His book has been criticized for its intemperate remarks about the Irish and their American great-grandchildren, but if Jimmy Breslin is not qualified to make those judgments, then for the love of God, who is? “You can blame the church’s condition on the Irish, who gave us total religious insanity,” he writes. “They are a race that sat in the rain for a couple of thousand years and promoted the most crazed beliefs in personal living outside of the hillbillies.”

Of course those are deliberately outrageous statements, and they don’t reflect the most nuanced understanding of Irish history. But I defy any Irish or Irish-American person to read them and not laugh the bitter laughter of recognition. Breslin is right that the Irish who came to America were the poorest of the dirt-poor, the wariest of a wary race, the likeliest to follow orders, ask no questions and do whatever was necessary to get along. While Ireland itself has blossomed in the last generation, Irish-Americans as a whole remain a conservative, conformist group, a race of insurance salesmen, accountants and sentimental drunks.

“You couldn’t have the religion they were running unless you had a lot of impoverished peasants to follow you,” Breslin says. “Peasants who do what they’re told.” The church hierarchy may believe it has a new generation of peasants to dominate — immigrants from Latin America, Africa and the Philippines now form the bedrock of the American church — but there is clearly a problem. The hierarchy and the priesthood are still overwhelmingly composed of aging Irish-Americans, and the supply of young men willing to take a vow of chastity to enter a dubious profession whose prestige is shattered has evaporated. (Many dioceses have begun importing young priests from Africa, which has created new racial and cultural dilemmas.)

Breslin remembers being at a church luncheon a few years ago when the late Cardinal John O’Connor, then the New York archbishop, offered to personally drive any interested young man to the seminary. “There were, I think, seven men training for the priesthood in the New York archdiocese at that time,” Breslin says.

“It’s a lifestyle that has been demolished by the steady change in the pages of the calendar. You can’t ask young people today to lead such a cold, restricted life. There was an era when a mother with four children in Queens proudly sent one of the sons off to become a priest. It was like becoming a congressman or senator, a tremendous thing. The family was proud and the kid was proud. He wasn’t in there to hide from sex, he was in forward motion, he was doing something. Now that’s gone. We don’t get that anymore.”

In his book, Breslin dares to imagine a renewed and liberated vision of the Catholic faith. His faith and the Roman Catholic Church as it now exists, he writes, are different things, “separate and unequal.” He imagines people holding masses in their homes, around the kitchen table, leaving the priesthood and the hierarchy behind. He imagines Catholics who cast off the church’s wealth and grandeur, following the example of a certain Jewish carpenter who wore cast-off clothes, slept rough and threw the money-changers out of the temple. (When I suggest that from the point of view of religious history this idea of an intimate and personal Christian faith already exists, and that it is called Protestantism, Breslin doesn’t want to hear it.) He imagines a new church in which the priesthood is open to men and women, married or single, gay or straight.

He imagines himself ending his career as a priest or bishop in this new church. Reading his book, I thought he was kidding, but as he talks about it now I can see that he isn’t. “My wife — she’s Jewish, but forget the religion for a minute — if we were at a parish, we’d get housing,” he says. “And it’s good brick housing usually. I would do the sermons. She’s a politician, she could do the social work wonderfully. It would be a good, productive life, one you could be proud of and enjoy.”

It’s a wistful, genial image — the aging but unquenchable newspaperman-turned-priest with the Jewish wife, ensconced in the good brick housing and noble social work of a modest Queens parish. But Jimmy Breslin knows the Catholic Church will not be redeemed in this way, not in his lifetime or mine. His housing will continue to be a Manhattan high-rise and his sermons will appear three times a week in the pages of Newsday.

He pauses and you can see the sadness of a man who has left the church of his fathers behind, late in life. Could the current Catholic hierarchy do anything, I ask, to get him back? He shrugs. “They can go. Just go.”