"[S]ifting through so-called reality TV has become like rummaging through a landfill: There seems to be no end to the quantity and types of trash you'll find ... [I]f we're going to start setting taste standards for reality TV, there's going to be a lot of dead air time." [Myrtle Beach Sun News, 9/2/04]

"This is not just bad television in the sense that it's mediocre, pointless, puerile even. It's bad because it's damaging." -- BBC journalist John Humphrys, in a speech to U.K. TV executives [Reuters U.K., 8/27/04]

"Reality TV is so cheap because you don't need writers, actors, directors ... it is killing off new talent and we are all worse off for that." Rebecca of Cambridge, U.K. posting on BBC News, 8/28/04]

"Reality TV, in particular, mocks committed relationships and makes trust seem foolish, some teens said. So teens tend to 'hook up' with friends to get a sexual fix without the responsibility of a relationship." [Richmond Times-Dispatch, 9/7/04]

"Sarah Austin occasionally watches reality TV, but finds it sad, rather than engaging." The Age, 9/5/04]

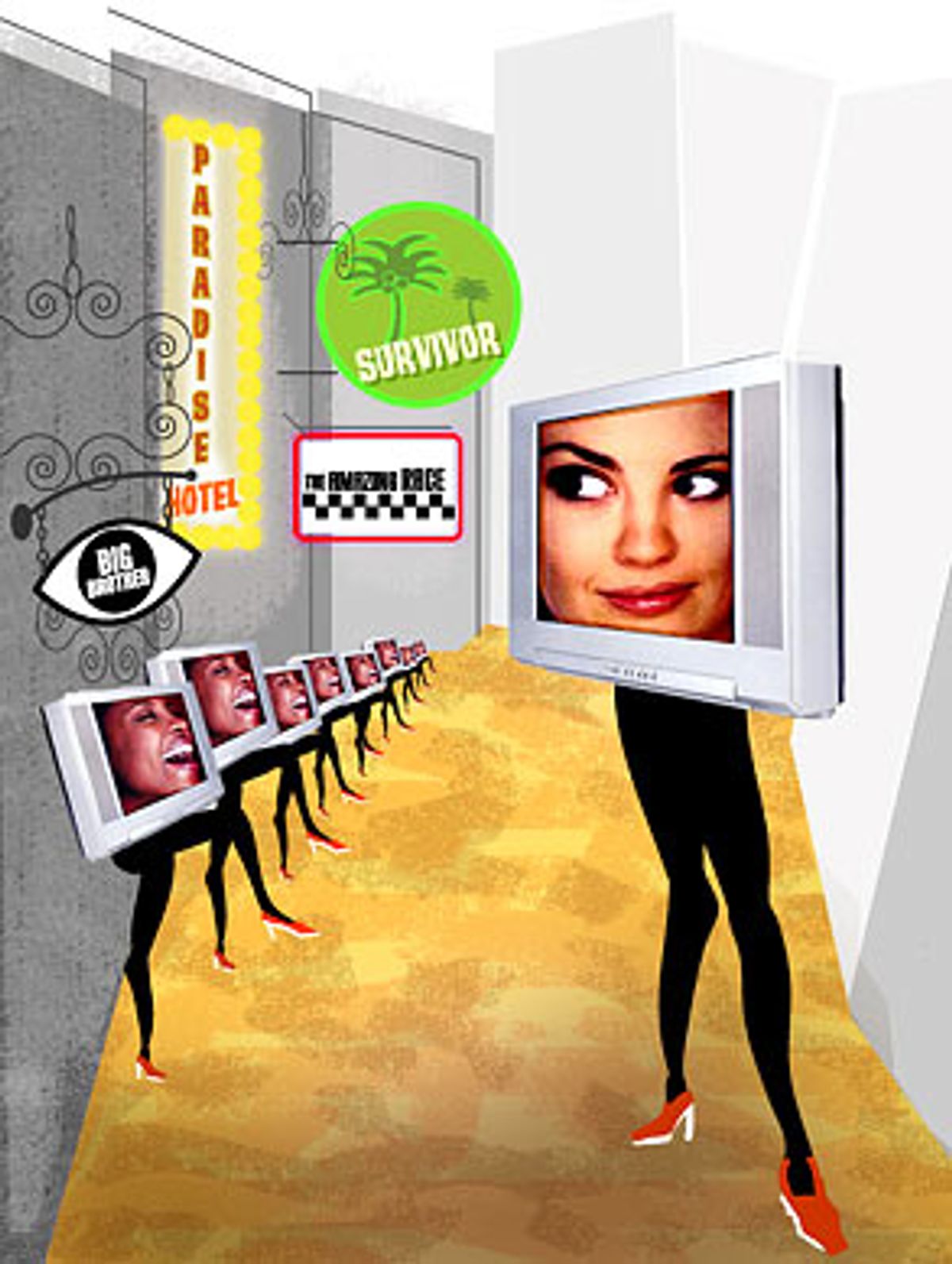

Welcome to the modern world, where we're all sucking on the same pop cultural crack pipe, but only the unrefined among us will admit that they inhale. Reality TV earns its reputation as the dangerous street drug du jour mostly by aiming its lens at human behavior -- we're far less photogenic than we imagine ourselves to be. While shows run the gamut from high-quality, dramatically compelling work to silly, exploitative trash, pundits consistently point to programs at the bottom of the barrel and cast aspersions on those foolish enough to watch them. Thanks to this stigma, it's not always easy to get a clear picture of how many people genuinely enjoy reality shows and aren't about to give them up.

Instead, every few months, a new survey announces that reality is on its way out. Last March, an Insider Advantage survey found that "67 percent of Americans" were "becoming tired of so-called reality programs." This year, a survey by Circuit City concluded that 58 percent of viewers are "getting tired" of reality TV. (What are they excited about? Why, HDTV, of course -- they just can't wait to purchase their new HDTV-capable sets!) Can you expect accurate results when you ask people if they're "getting tired" of anything? But even while many people take their cue from the media and bemoan the evils of reality, they're still watching. Just as there are those who claim to read Penthouse for the fine articles, no matter how "sad, rather than engaging" reality TV might be, audiences have yet to drop off as predicted.

"Reality TV is not going away," says Marc Berman, television analyst for Mediaweek. "This summer, reality dominated. In terms of total viewers during the regular season, three of the top five shows ["The Apprentice," "American Idol" and "Survivor"] were reality shows." Berman predicts that we'll see these same reality shows pull in big numbers in the fall, along with frequent time-slot winners like "The Bachelor" and whichever new reality programs draw in big audiences. "The bottom line is that the genre is absolutely exploding," Berman says.

Instead of writing off millions of viewers as the unenlightened consumers of lowbrow entertainment, shouldn't we ask why they're attracted to reality TV in the first place?

First of all, viewers have been exposed to the same half-hour and hour episodic plot structures, implemented in roughly the same ways, for decades now, setting the stage for a less conventional format. Even once-groundbreaking, high-quality dramas like "ER" and "The West Wing" have evolved into parodies of themselves, with all the usual suspects striding through halls and corridors, spitting out the same clever quips until the next big tragedy hits. Meanwhile, traditional sitcoms are faring even worse, as the networks spend millions each fall to develop shows that don't stick. While those in the industry bemoan the fact that the networks have whittled their sitcom offerings down to two or three shows, that makes perfect sense when you recognize how bad TV executives have been at locating genuinely good shows, and how expensive it is just to develop a handful of episodes. "Two and a Half Men," one of the only new sitcoms from last fall to make it to another season, is considered a hit, yet it's not remotely funny. And the best sitcoms -- "Everybody Loves Raymond," "Will & Grace" and "That '70s Show" -- are all winding down, with one-half ("Raymond") to two years left in them, at most.

That's not to say that the world of scripted entertainment is dead -- far from it. Instead, new formats are taking hold: one-camera sitcoms like "Arrested Development" and "Entourage," sketch comedies like "Chappelle's Show" and "Da Ali G Show," and unconventional twists on old formulas like "Deadwood" and "The Wire." But unconventional means risky, which is why none of those shows are on the Big Three networks, which seem as faithful to old-formula fiction as Joanie was to Chachi.

Ultimately, though, it's not the basic format of the traditional sitcom or drama that's to blame, it's the lack of original, high-quality writing. By now everyone knows that HBO, a channel not poisoned by the copycat mentality of the networks, is behind most of the best shows on television. Many producers and writers report that quality scripts and ideas are out there, but the networks aren't necessarily looking for quality. What seems familiar about those wisecracking characters on their couches isn't the setting or the format, it's the mediocre jokes and story lines that simply mimic the story lines of other better -- but not necessarily great -- shows. Sadly, as the networks continue the impossible search for guaranteed hits and sure things, they limit their scope to the sorts of shows that have succeeded before instead of seeking original voices with something to say. This is why we'll end up watching soggy star vehicles like John Goodman's "Center of the Universe" and Jason Alexander's "Listen Up" (It worked with Charlie Sheen, right?) this fall instead of encountering truly original comedies with fresh, surprising characters.

Will we be watching? The truth is, the best reality shows feature exactly the kinds of fresh, surprising characters that most sitcoms and dramas lack. For those who care about the quality of reality shows they produce, the bar has been set very high by Mark Burnett. At a time when reality TV appeared to be shackled to the somewhat shallow teenage-bitch-slap tradition of "The Real World," Burnett insisted on bringing the same intelligent editing and beautiful cinematography to "Survivor" that he brought to "Eco Challenge." He recognized that, beyond painstakingly careful casting and crafting of dramatically compelling story lines, viewers would want to get a real feel for the show's exotic setting. As fleeting as those aerial and wildlife shots can seem, they add an inestimable dimension to the viewer's experience. Anyone who watched the first few episodes of "Survivor" knew that the show was bound to be a hit, and the reason for that had more to do with sparkling shots of cornflower-blue water than it had to do with Richard Hatch (although having a naked, backstabbing provocateur around certainly helped).

If reality offerings were limited to claustrophobic, repetitive, aesthetically irritating shows like "Elimidate" or "The Bachelor," it would be easy to write off the entire genre as the work of sensationalistic producers churning out trash for a quick buck. Instead, a few sharp producers like Burnett saw the enormous potential of the form and approached it with a passion, creating a vicarious experience for the viewer. They recognized that reality TV could truly engage audiences, pulling them into a time and place, populated by real human beings. As long as the cast and the settings were a little larger than life, as long as the stories were edited to make the viewer feel like a personal confidante to each of the competitors, audiences would find themselves swept into the action, investing far more of their emotions in the competition than they imagined was possible.

"The Amazing Race" followed in the footsteps of "Survivor" in terms of quality, but conquered the most difficult production challenges imaginable. Ten teams of two scamper across the globe, racing to complete various tasks, but you never, ever spot a single camera, not when several teams are running across a beach to the finish line, not when they're hang gliding or walking teams of dogs or eating two pounds of Russian caviar. Produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and edited with so many suspense-inducing tricks it's impossible not to get caught up in the action, "The Amazing Race" took Burnett's high standards of human drama and visual appeal and built on them. Lumping together an intensely difficult, expensive, painstakingly produced show like "The Amazing Race" with meandering, silly shows like "The Ultimate Love Test" is an insult to the sharp, talented people who seem to set the bar higher each season.

Of course, meandering, silly shows have a certain charm of their own. Fox's "Paradise Hotel" stumbled on accidental genius with its hyperaggressive cast of frat boys and neurotics. Originally intended as a sleazy dating show where those guests who didn't "hook up" would get thrown out of Paradise "forever!" as the voice-over put it, "Paradise Hotel" evolved into a nasty battle between two cliques, with the producers scrambling to mold their "twists" and promos to fit the bizarre clashes arising on the set. There's something to be said for a show that evolves based on the strange behavior of its cast, thanks mostly to the fact that its cast is made up of belligerent drunks. Sadly, "Paradise Hotel's" success was purely accidental. The producers foolishly moved the show away from its original location, a gorgeous Mexican resort with brilliant white walls that lit every scene beautifully, making all of the inhabitants appear larger than life. They renamed the show, cast it with bland, empty-headed Neanderthals, added an even-more-awful host and some pointless twists, and the magic was over. The ironically titled "Forever Eden" was canceled before the season ended.

But part of the joy of watching, for true reality aficionados, is witnessing such false starts and mesmerizingly entertaining mistakes. While those who've never seen much of the genre bemoan the foolishness of most shows, it's the newness of the form that makes it so exciting. When not even the producers can predict how the characters on a show will react, audiences feel like they're a part of something that's evolving before their eyes. The second season of "The Joe Schmo Show," titled "Joe Schmo 2," epitomized this state. The show lures two individuals into thinking that they're contestants on a dating show called "Last Chance for Love," when in fact, their fellow contestants are really actors, paid to create absurd, funny scenarios.

To the dismay of the show's producers and crew, a few episodes in, one of the two Schmos named Ingrid figured out that something was very wrong, and kept asking the actors around her if they had memorized the things they were saying, or there was "some kind of 'Truman Show' thing going on." Instead of declaring the show a failure, the producers chose to reveal the truth to Ingrid and then enlisted her as an actor for the rest of the show. This kind of behind-the-scenes, seat-of-the-pants improvisation is such completely new territory, it's not hard to understand why audiences are intrigued.

Furthermore, if our obsession with celebrities tends to rise and fall and rise again in cycles, then it makes sense that reality TV would become popular in the wake of the late '90s, when celebrity obsession reached new levels of absurdity. Audiences bored with Brad and Jennifer or Jennifer and Ben or Paris and Nicole suddenly found themselves with more knowable, less remote personalities to root for. Instead of focusing all their attention on those far too privileged to comprehend or relate to, audiences could embrace no-nonsense, surprisingly open-minded Rudy of "Survivor" or despise the outspoken-but-bellicose Susan Hawk. Reality "stars" like lovable couple Chip and Kim from "The Amazing Race" or country-boy Troy from "The Apprentice" offer us a chance to admire real people for qualities that go beyond choosing the perfect dress for the Oscars or smiling sweetly for the cameras.

Plus, now that magazines like InStyle make it clear that a major celebrity's image and personality are essentially created by a team of stylists, interior designers, assistants, managers and publicists, it's no wonder we crave an exploration of the little quirks and flaws of ordinary people. And when it comes to making enemies, anyone can throw a temper tantrum and then stalk offstage, but how many ordinary humans can manage the messy explosion of insults and accusations set off by Omarosa of "The Apprentice"? Who knew that "Now there's the pot calling the kettle black!" was a racial slur?

Many have argued that self-consciousness will be the death of the genre. As more and more contestants who appear on the shows have been exposed to other reality shows, the argument goes, their actions and statements will become less and less "real." What's to blame here is the popular use of the word "reality" to describe a genre that's never been overtly concerned with realism or even with offering an accurate snapshot of the events featured. In fact, the term "reality TV" may have sprung from "The Real World," in which the "real" was used both in the sense of "the world awaiting young people after they graduate from school," and in the sense of "getting real," or, more specifically, getting all up in someone's grill for eating the last of your peanut butter.

The truth is, part of the entertainment offered by reality TV lies in separating the aspects of subjects' behavior that are motivated by an awareness of the cameras from the aspects that are genuine. You can't expect someone who's surrounded by cameras to act naturally all of the time, and as the genre has evolved, editors and producers have become aware that highlighting this gap between the real self and the camera-ready self not only constitutes quality entertainment, but may be the easiest shortcut to creating the villain character that any provocative narrative requires. When "Big Brother 5's" Jason pouts his lips, flexes his muscles and adjusts his metrosexual headband in the mirror, then confides to the camera that every idiotic thing he's done in the house so far has been part of a master plan to confuse his roommates, he not only makes a great enemy for the more seemingly grounded members of the house, but he also hints at narcissistic and sociopathic streaks that reality TV has demonstrated may be a defining characteristic of the modern personality. Either an alarming number of reality show contestants are self-obsessed and combative, or the common character traits found in young people have shifted dramatically.

In our self-conscious, media-savvy culture, such posturing and preening are a worthy subject for the camera's gaze, documenting as they do the flavor of the times. When young kids talk about marketing themselves properly and "breaking wide," it makes perfect sense to shine a light on the rampant self-consciousness and unrelenting self-involvement of these characters. When we see Puck of "The Real World" screeching at the top of his lungs or Richard Hatch of "Survivor" confiding to the cameras that he considers the other players beneath him, we may be glimpsing behavior that's more true of the average American than any of us would like to believe.

But then, no matter how premeditated many of the words and actions of reality show stars can be, the proper events and tasks eventually conspire to create cracks in the shiny veneer, revealing flaws and personality tics they'd clearly wish to hide. If even the smooth operators of "The Apprentice" stumble on their words, bare their claws and show their less polished selves regularly, you have to figure that keeping your true self hidden from the camera is more difficult than it looks. Katrina, for example, started the first season appearing smooth and polished, then slowly unraveled as the personalities and tactics of the players around her seemed to erode her sense of self. And who can forget Rupert on "Survivor," who went from lovable teddy bear to snarling grizzly whenever someone crossed him? Real people are surprising. The process of getting to know the characters, of discovering the qualities and flaws that define them, and then discussing these discoveries with other viewers creates a simulation of community that most people don't finding in their everyday lives. That may be a sad commentary on the way we're living, but it's not the fault of these shows, which unearth a heartfelt desire to make connections with other human beings. Better that we rediscover our interest in other, real people than sink ourselves into the mirage of untouchable celebrity culture or into some überhuman, ultraclever fictional "Friends" universe.

Naturally, there will always be those shows that heedlessly propagate crass televised stunts without any socially redeeming qualities. "The Swan," which turns normal, attractive women into hideous plasticized demons with lots of pricey plastic surgery, then pits the demons against each other in a beauty contest, is more freakishly dehumanizing than anything George Orwell could've dreamed up. "Gana La Verde," a "Fear Factor"-style competition where immigrants compete for a green card, or at least for the use of lawyers who might win them a green card, makes you wonder if we're not one step away from feeding the underprivileged to the lions on live TV. But the lowest rung on the reality ladder has nothing to do with the sharp, fascinating shows at the top. The best reality shows transform ordinary places and people into dramatic settings populated by lovable heroes and loathsome enemies, and in the process of watching and taking sides and comparing the characters' choices to the ones we might make, we're reacquainted with ourselves and each other. Great fictional TV has the power to engage us, too, but the networks aren't creating much of that these days. When was the last time "CSI" sparked a little self-examination? Does "Still Standing" make you giggle in recognition at life's merry foibles?

Lowbrow or not, all most of us want from TV is the chance to glimpse something true, just a peek at those strange little tics and endearing flaws that make us human. While the networks' safe little formulas mostly seem devoid of such charms, reality shows have the power to amuse, anger, appall, surprise, but most of all, engage us. Isn't that the definition of entertainment?

Shares