Three years after the attacks on the World Trade Center, attacks in which they played no part, the people of Iraq have been liberated from one tyranny only to be remanded to another: continuous urban warfare, religious extremism and a contagion of fear. The celebrated hand of the free market in Iraq has brought not only cellphones and satellite TV, it has also brought down prices for automatic weapons, making them affordable to the average Iraqi. The last time I checked, a rocket-propelled grenade launcher cost about $250.

In his address to the United Nations on Tuesday, President Bush told a subdued General Assembly, "Today, the Iraqi and Afghan people are on the path to democracy and freedom. The governments that are rising will pose no threat to others. Instead of harboring terrorists, they're fighting terrorist groups. And this progress is good for the long-term security of us all." The words of the president ring hollow.

It is words to this effect that Iraq interim Prime Minister Ayad Allawi will likely echo during his visit to the White House Thursday.

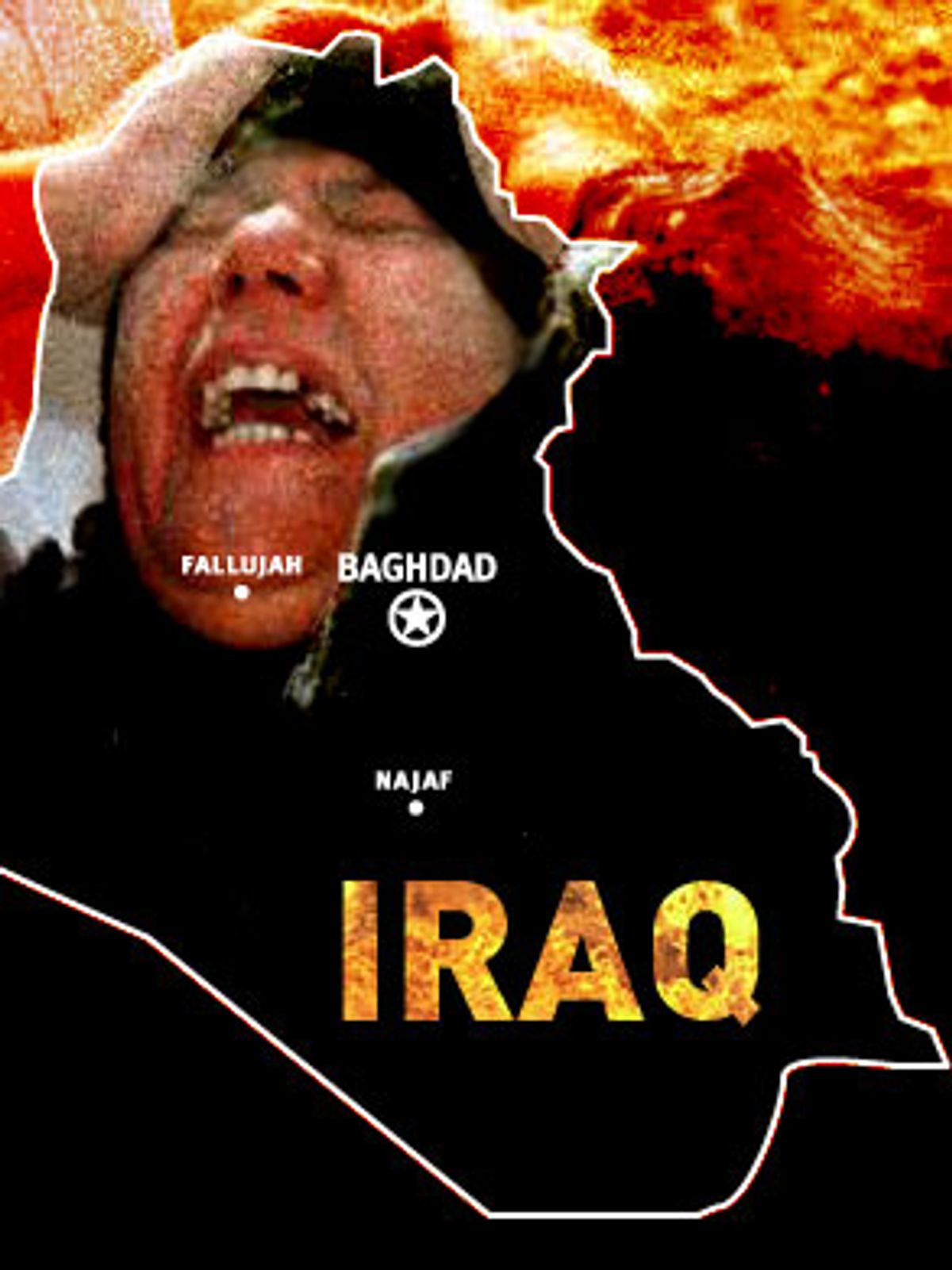

Reconstruction, the most important step on the path to a sovereign and stable Iraq, has all but stalled because of targeted acts of violence that reach all the way south to Basra and north to Mosul. Successful countermoves by the Sunni insurgents have prevented the United States and new Iraqi government from gaining any real political support. In fact, billions of dollars originally allocated for reconstruction are now headed for security companies, which are quickly becoming private militias. Unfortunately for optimistic planners in the Bush administration, the coalition is up against not one single group but a constellation of allied militias. It's as if the United States had gone to war against the tribal system itself. There are so many new fighter cells that they are at a loss to distinguish themselves, and so use kidnapping and videotapes as branding strategies. In this market, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's Tawhid wa al Jihad, with its monstrous beheading trademark, is the undisputed brand king. Some of the groups are crazier than others. It is a free market of demons.

In the past year, al-Qaida operatives have found in Iraq a fertile recruiting ground, the best possible training camp for jihad against the West, a destination any angry young man can reach if he has the will and pocket money. Iraq's borders, which stretch across hundreds of miles of empty desert, are perfect for smugglers and men seeking martyrdom. No one really knows how many people are coming into Iraq to fight the U.S. But the fighters who do make it across are changing the character of the resistance, internationalizing it, injecting religious extremism into the politics of a once-secular Iraq. Young men coming in from other countries don't fight for Iraq, they fight for Islam.

One of the unutterable truths for the administration is that the U.S. occupation is breeding and fueling insurgent groups. Iraqi government officials rightly fear for their lives, but Iraqi forces, which are supposed to be fighting alongside U.S. troops in the cause of a free and democratic Iraq, are often undisciplined, dangerous and in some places infiltrated by insurgent groups. The Mahdi Army in Sadr City has a number of police officers in its ranks, and in a little remarked upon event that took place during one of the large demonstrations in Baghdad at the time of the siege, the Iraqi police helped Sadr officials address a crowd of Muqtada al-Sadr supporters outside the neutral Green Zone.

On Aug. 13, with U.S. troops looking on, a Mahdi Army sheik urged the followers of Muqtada al-Sadr to go to Najaf to support the men occupying the shrine. He used a public address system in the back of a police pickup to get his message across. The fighters were yelling and grabbing at journalists, proud that the police were on their side, and they wanted us to take note. Above us, in their watchtowers, Iraqi police hung pictures of Muqtada al-Sadr and waved to the crowd. The organizers of the rally were overjoyed.

Fringe groups, extreme groups, associations with the most vocal opposition to the U.S. occupation, steadily acquire more legitimacy in Iraq because they tend to express the true feelings of many Iraqis. Not everyone takes part in the fighting, but many people understand why the groups choose to fight. Jobs in the Iraqi National Guard and the Iraqi police tend to attract poor men who desperately need the money, while the insurgents attract believers, men who feel wronged and humiliated by the U.S. occupation, and who will work for nothing. They are volunteers. Which emotion is stronger?

Iraq is a place where there is no civil debate and interest groups mediate their conflicts with weapons. The U.S. has the most powerful armed presence, its own military, but as an interest group, it represents the smallest number of Iraqis, possibly only those it directly supports. Political legitimacy, we have long known, comes directly from the people; it is not something that can be dictated by a foreign power, no matter how noble its stated intentions. The Allawi government, the result of American occupation, is what many Iraqis scornfully call a U.S. puppet government. In the months following the "transfer of sovereignty," I never heard a single Iraqi offer up praise for it. Not one.

The Sunni insurgents, a creepy hodgepodge of extremist imams, tribal sheiks, former Iraqi government officials and al-Qaida types, have not only scuttled the plans to rebuild the country, they have also cornered the political debate. Relying on abundant examples of victimization and prejudice against Iraqis and Muslims, the fighters present themselves as defenders of the faith. Kidnapping, execution and death threats have become acceptable practices in the eyes of some ordinary Iraqis who may have been horrified by it only a few months before.

When a well-educated Sunni shop owner named Abu Mustapha heard about the kidnapping of French journalists Georges Malbrunot and Christian Chesnot, he wanted to express his sympathy. It sounded like this: "Phillip, it is very bad that they were kidnapped. You should be careful." I pointed out that the people who were abducting noncombatants and threatening to kill them were behaving like animals. The hostage-takers were demanding that the French government repeal a law prohibiting religious symbols from being worn in schools. Abu Mustapha agreed with the insurgents. "You know, the French should change their law," he said. "It is a bad law. Muslim girls should be able to wear the hejab in school."

Contrary to the administration's hopeful statements, we are not seeing the establishment of a stable Iraq, the mopping up of unreformed Baath Party apparatchiks and dead-enders. We are seeing the beginning of a larger conflict that is busily giving birth to monsters.

Since April, the coalition has lost ground in central and western Iraq and will be forced in the coming months to gain it back at great cost. Fallujah and Ramadi, two sizable Iraqi cities, are no longer under Iraqi government control. Sadr City, with several million people, remains a stronghold for the Mahdi Army and the site of a continuing series of battles. Najaf and Karbala, cities the military has taken back from the Mahdi Army, were never strongholds of the Shia resistance. In Najaf, citizens paid a high price for emancipation. They experienced the destruction of their city and must now set about rebuilding it, a process that will take years. It is hard to imagine that the U.S. is loved in Najaf. While the siege may have been a military victory, it was a political defeat. I left Najaf just as men were beginning to dig out bodies.

But Najaf did not serve as the headstone for the Mahdi Army; at best, the military defeat set them back a few months, driving them deeper underground. The first cavalry division and the Marines successfully routed the Muqtada fighters, pushing them to other cities, scattering them but not destroying them. In my second to last day in Najaf, at the end of the siege, journalists in the old city watched militiamen load wooden carts full of weapons and take them to new hiding places. When we asked where they were going, one fighter said to a comrade in an alley just off Rasul Street, "Don't talk to these people, some of them are spies." That was a perfectly normal response and we didn't take it personally. But it was clear that they weren't taking their anti-aircraft weapons and rockets to U.S. collection points for cash payouts. The skittish Mahdi Army fighters were busy smuggling their weapons out of town to other cities and a number of them were almost certainly headed for Baghdad. We watched them trundle the carts over the streets, trying to keep the weapons from spilling out onto the cobblestones.

Here is something everyone in Iraq knows: The U.S. is now fighting a holding action against a growing uprising, and the more it fights the worse it gets. At the other end of the spectrum, if the U.S. military were to suddenly withdraw, the largest armed factions in Iraq would immediately begin to compete for the capital in a bloody civil war. Recently, a National Intelligence Estimate, a document prepared for President Bush by senior intelligence officials, warned of exactly that outcome. It is the kind of analysis that Secretary of State Colin Powell might write off as defeatist if it had come from the press.

How much control does the U.S. military have over the country? Not as much as it would like. Large sections of the capital are in the hands of insurgents, and organized attacks on convoys, U.S. interests and Iraqi targets are on the rise. The administration can say things are getting better, that a newly democratic Iraq is facing its enemies, but last week Baghdadis woke up at 5 in the morning to the sound of a large volley of rockets slamming into the Green Zone. The explosions sounded like they were coming from more than one direction, the sign of a carefully coordinated attack.

This summer, it wasn't unusual to wake up to the sound of roadside bombs going off near Humvees on their early morning U.S. patrols. Month by month, attacks became more severe, bombs more powerful. In the sky above the Duleimi hotel, medevac helicopters would shudder through the air on their way to combat support hospitals. When something truly ugly was going on, we could hear the rush of the medevac Black Hawks in a steady progression.

What the war's champions prefer to ignore is that in large parts of Iraq, broad support exists for anyone willing to pick up a gun and fight the United States. Fighters become local stars and when they die, their friends hold their photographs as treasured objects, pass them around at parties, and later try to emulate their fallen buddies. Paradise awaits, full of virgins who have bodies made of light. Many young Iraqi men believe this. A young fighter guarding the bottom of Rasul Street in Najaf said, just before the collapse of the truce on Aug. 4, "Paradise is a place without corruption. It's not like this place, it smells sweet." Thousands of Iraqis, not all of them poor and unemployed, have checked into the resistance, not only because it's honorable but because it's fun. Spreading through family and neighborhoods, the insurgency can be anywhere, anytime.

A young Apache helicopter gunner who has fought in many of Iraq's major battles wrote me a few days ago and said: "I have a feeling that with every one member of the resistance that we kill, we give birth to ten more." At a distance of hundreds of feet in the air, a perceptive man can say this. Here is what the situation looks like from the ground.

Iraq seems modern only at first glance. The highways, factories and cities are familiar enough but they hide a deep tribal sensibility. Insults to family honor in Iraq are usually repaid in blood or money depending on the severity, and this system of revenge and honor fuels the war instead of slowing it down. The United States military, unable to relate to a tribal society, finds itself the player in a nationwide blood feud. To understand the intensity of these feelings of honor and kinship, read "Othello" or watch "The Godfather." This is how many tribal Iraqis perceive the world. It is not necessarily a lack of sophistication but a mark of being outside the West. Tribal culture in Iraq goes back thousands of years. When an Iraqi man loses a family member to an American missile, he must take another American life to even the score. He may not subscribe to the notion that some Americans are noncombatants, viewing them instead as the members of a supertribe that has come to invade his land.

The war, illegal and founded on a vast lie, has produced two tragedies of equal magnitude: an embryonic civil war in the world's oldest country, and a triumph for those in the Bush administration who, without a trace of shame, act as if the truth does not matter. Lying until the lie became true, the administration pursued a course of action that guaranteed large sections of Iraq would become havens for jihadis and radical Islamists. That is the logic promoted by people who take for themselves divine infallibility -- a righteousness that blinds and destroys. Like credulous Weimar Germans who were so delighted by rigged wrestling matches, millions of Americans have accepted Bush's assertions that the war in Iraq has made the United States and the rest of the world a safer place to live. Of course, this is false.

But it is a useful fiction because it is a happy one. All we need to know, according to the administration, is that America is a good country, full of good people and therefore cannot make bloody mistakes when it comes to its own security. The bitter consequence of succumbing to such happy talk is that the government of the most powerful nation in the world now operates unchecked and unmoored from reality; leaving us teetering on the brink of another presidential term where abuse of authority has been recast as virtue.

The logic the administration uses to promote its actions -- preemptive war, indefinite detention, torture of prisoners, the abandonment of the Geneva Convention abroad and the Bill of Rights at home -- is simple, faith-based and therefore empty of reason. The worsening war is the creation of the Bush administration, which is simultaneously holding Americans and Iraqis hostage to a bloody conflict that cannot be won, only stalemated.

Over the last three years, practicing a philosophy of deliberate deception, fear-mongering and abuse of authority, the Bush administration has done more to undermine the republic of Lincoln and Jefferson than the cells of al-Qaida. It has willfully ignored our fundamental laws and squandered the nation's wealth in bloody, open-ended pursuits. Corporations like Halliburton, with close ties to government officials, are profiting greatly from the war while thousands of American soldiers undertake the dangerous work of patrolling the streets of Iraqi cities. We have arrived at a moment of national crisis.

At home, the United States, under the Bush administration, is rapidly drifting toward a security state whose principal currency is fear. Abroad, it has used fear to justify the invasion of Iraq -- fear of weapons of mass destruction, of terrorist attacks, of Iraq itself. The administration, under false premises, invaded a country that it barely understood. We entered a country in shambles, a population divided against itself. The U.S. invasion was a catalyst of violence and religious hatred, and the continuing presence of American troops has only made matters worse. Iraq today bears no resemblance to the president's vision of a fledgling democracy. On its way to national elections in January, Iraq has already slipped into chaos.

Shares