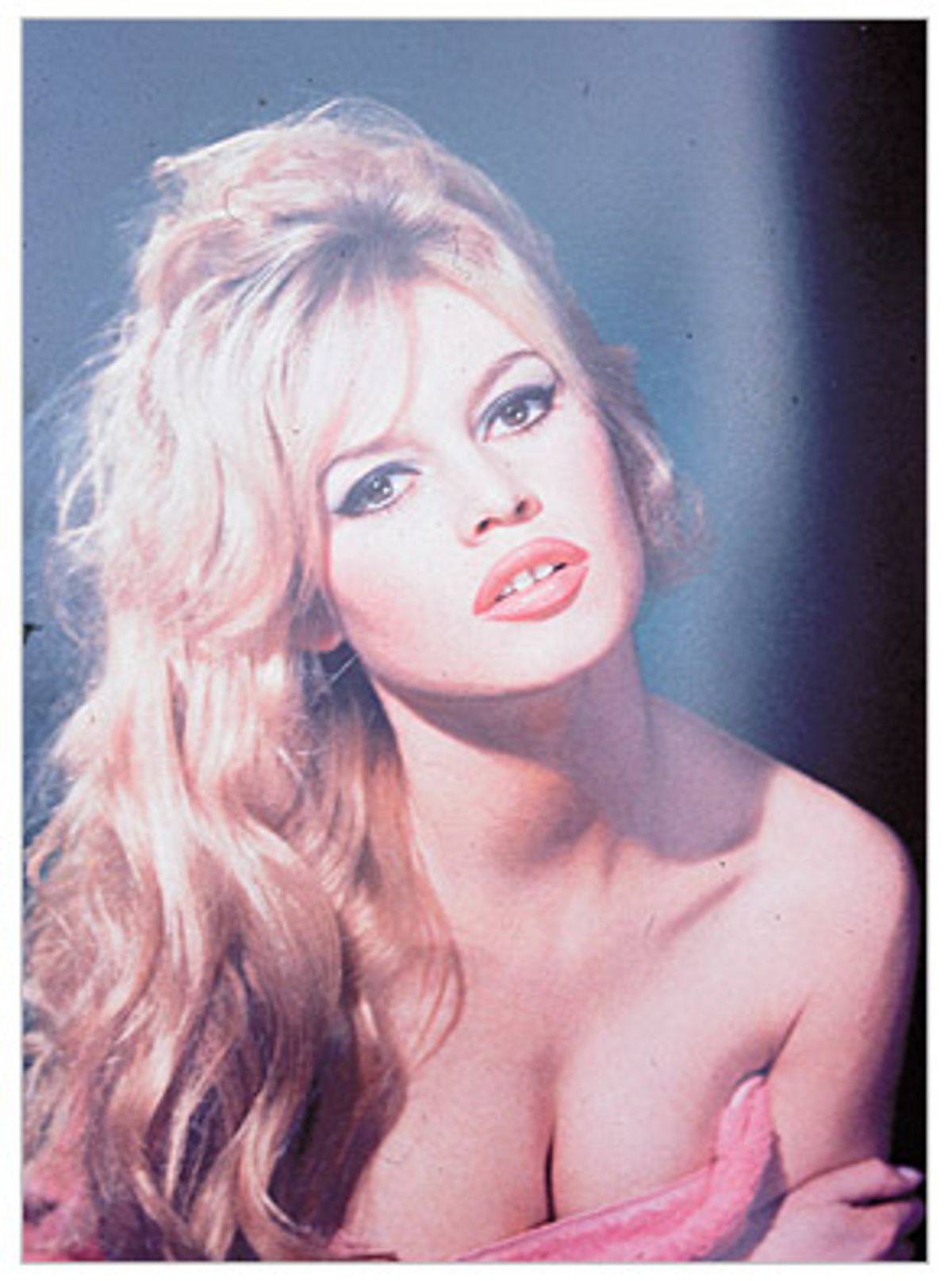

It's the hair that always gets me. Yes, her body was fabulous, but the magic took place from the shoulders up. Those sparkling almond eyes; the laugh ("a soft brusque laugh that broke into shining crystals" -- Rimbaud); the full lips always slightly parted in anticipation, revealing a fetching gap between the two prominent front teeth; and above all, that messy blond mane. The sight of Brigitte Bardot's hair, as luxuriant and inviting as a love-tousled bed, will always go right to my blood stream. Ever since I first saw her in a movie, I have loved Brigitte Bardot without reason or cessation. She is my ultimate.

Bardot turns 70 on Sept. 28. Thirty years ago, on her 40th birthday, Bardot, who retired from movies in 1973 mainly to devote herself to animal rights (she never cared much about being a movie star), said, "The myth of B.B. is finished. Perhaps in five years people will have forgotten me, maybe not."

As a movie star, she has been just about forgotten in America. In France, Bardot is far from forgotten, though it's unlikely that her 70th will bring her many happy returns from the public. This past June, for the fourth time since 1988, a French court fined Bardot for inciting racial hatred. The cause this time was her book "Un cri dans le silence," which attacks "the Islamization of France." (Her 1998 autobiography, "Initiales B.B.: Mémoires, also resulted in fines.) Vocally supportive of Jean-Marie Le Pen's fascist National Front and married to a member of the party, Bardot also, in "Un cri dans le silence," apparently condemns homosexuals ("fairground freaks"), interracial marriage, unemployment benefits and women in government.

Do I find this an ugly legacy? Yes. Does it affect my pleasure watching her? No. Anyone old enough to remember when some people wouldn't go see Jane Fonda movies and others wouldn't go see John Wayne movies (though, to be fair, neither was espousing fascism) knows how easy it is to ignore people's work because of the vociferousness or silliness of their political statements.

The Bardot I want to celebrate here is the one onscreen. I first encountered Bardot playing herself (a cameo) in a 1965 horror called "Dear Brigitte" about a little-boy math prodigy (Billy Mumy from "Lost in Space") who writes a love letter to her every night. At Bardot's invitation, he travels to France with dad James Stewart to meet her. Bardot is saddled with dumb jokes about not being able to speak English and Mumy sits silently gazing at her like a lovesick leprechaun.

I was about Mumy's age when I saw the movie, but my reaction hasn't changed over the years. Even when I run across the picture on TV today, I want to shake the little twerp. He's blowing a chance to meet Brigitte Bardot! And yet I suspect part of what makes me mad is the suspicion that it would be easy to be reduced to adoring idiocy in front of Bardot. There are stars who have affected me more. There are better actors. There are those whose personas are deeper, more mutable, more mysterious. But there is none who inspires in me such a distinctive mixture of desire and delight.

Watching Bardot you feel none of the embarrassment you sometimes do watching sex symbols wriggle and wiggle. When she exaggerates her sexuality, it's in pursuit of laughs, not seduction -- and the joke is usually that she doesn't realize she has sex appeal to exaggerate. Performing a music-hall number with Jeanne Moreau in "Viva Maria!" Bardot, suffocating in the constricting confines of her merry widow, impatiently tugs the boa collar over her shoulder to give herself some breathing room. When the men in the audience let out a collective "oooohh" in anticipation of even more disrobing, she stops and smiles at them, suddenly realizing she's done something they find sexy and only then affecting sensuality, touching her chin to her shoulder in a teasing moue. She's like a kid who does something that adults find adorable and hams it up to get even more kitchy-kitchy-koos.

Untutored performers can get away with things that trained actors can't, probably because they lack the guile to calculate how to go about getting an effect. Bardot was especially adept at a certain type of comic innocence. In movie after movie she gets laughs out of the expression of wide-eyed shock she employs when she finds something startling. There's a disconnect between the way she looks and the naiveté she displays, as there is between the two sides of her nature, sweet and demure one moment and capable of public displays of childish impatience the next.

In the 1961 "Please Not Now!" (the best of her comedies) she thinks nothing of barging into a men's room to have a fight with her philandering fiancé, and nothing of pushing the old man desperate to use the facilities out the door whenever he intrudes. In his 1986 memoir "Bardot, Deneuve, Fonda," Roger Vadim, Bardot's first husband and the man who made her an international star when he directed her in the 1956 film "...And God Created Woman," wrote that Bardot didn't understand her genius because she embodied both the proper bourgeois values of her upbringing and an unconscious sense of rebellion that challenged those values.

Judging from his account of their courtship, those clashing impulses made her young life hell. Vadim met Bardot when she was 15 and he was 21. Despite being chaperoned so thoroughly that her parents forbade her to see Vadim for two weeks after he kissed her on the subway (her sister was the stoolie), the two managed to secretly become lovers.

One day, Bardot's father, a successful industrialist, called her into his study, showed her a gun, and announced that if he ever learned she had become Vadim's mistress, he (her father) would shoot him. When Bardot told her mother that papa had gone crazy, her mother told her to calm down. In the event that her father couldn't shoot Vadim, Mme. Bardot explained, she would do it herself.

When the Bardots out-and-out refused to let the young Brigitte marry until she was 18, she very nearly succeeded in committing suicide one night while the family was out. When she was revived, the first thing her father said to her was, "How could you have done that to us?" (Bardot herself echoed the words at her father's funeral 20 years later, saying to Vadim, "Look what he has done to me!")

What is true of Bardot on-screen is that what was often misread for deliberate rebellion was, for her, merely acting natural. Like many other performers who have upset traditional morality, Bardot didn't set out to be scandalous. In the foreword to a 1975 book of Bardot photos by Ghislain Dussart, the late novelist Françoise Sagan wrote, "She has nothing in common with Christian civilization and its taboos, and therefore feels none of the destructiveness of hatred that comes from these taboos."

In "Bardot, Deneuve, Fonda," Vadim expanded Sagan's comments, saying Bardot had "no mystical or religious anxieties and none of the Judeo-Christian mishmash attached to the notion of pleasure ... She never thought of nudity as a secret weapon that enabled men to seduce women. Nudity was nothing more or less than a smile or the color of a flower. In this sense she was more painter than model -- or rather, both painter and model."

Given that both Sagan and Vadim invoke the guilt and hypocrisy of the Judeo-Christian tradition, then the greatest compliment given "...And God Created Woman" had to be the Vatican condemning it as "amoral." The Vatican may have been upset over a scene in which a priest (all we see of him are his plump fingers stuffing a pipe) says of Bardot, "That girl is like a wild animal. She needs to be tamed," which pretty much sums up the Catholic Church's conception of women.

But there was plenty more to upset the church. Vadim wasn't merely patting himself on the back when he said that what really shocked people about the movie's attitude toward sex is that it isn't shocked by sex. And he wasn't making an excuse for his displays of female flesh (not that he had to -- Vadim was the most decorous libertine the movies have ever had) when he said of some of the disapproving reviews, "Nudity and eroticism were acceptable in a woman only if she was an object. A whore or a prostitute was even better. You paid her and she became your property."

Which is why Bardot is the film's perfect emblem -- her character isn't a whore, and she won't allow herself to be owned by anybody. In our first glimpse of Bardot she is stretched out across the CinemaScope screen as she sunbathes nude. Far from being lewd, the shot evokes something innocent with Bardot giggling and kicking her feet like a kid. If you needed any proof that Bardot was a natural in front of the camera, it's in that shot. Not simply because she's beautiful to behold, with her pert derrière sticking wittily up in the air. But because she's totally nonchalant, totally at ease, and if someone can do that with their clothes off, then you know that being in front of the camera comes naturally to them.

"...And God Created Woman" is soapy, sometimes stiff, and a much more potent movie than it has a right to be. There's a subversive sensibility at work beneath the conventions. For one thing the visual beauty, the sand and sea and warm sun of St. Tropez (the yummy color photography is by Armand Thirard), communicate themselves physically to the viewer, creating an atmosphere that makes Bardot's response to the elements seem only natural.

She plays an orphan whose old crone of a ward threatens to return her to the orphanage. To prevent that, the shy young son (Jean-Louis Trintignant) of a local shipbuilding family marries her, even though Bardot is in love with her new husband's older brother. She has also attracted the attentions of a rich industrialist (Curt Jurgens, proving, as François Truffaut wrote at the time, "that he is one of the four worst actors in the world"). It's a predictable plot. The marriage awakens the shy husband's sexual pride, the attraction between new wife and older brother threatens that pride, and matters are resolved in favor of the union. But nothing about the movie's attitude or emphasis fits in with the way such stories were usually told at the time, or with what Bardot's career had been.

In the comedies Bardot made before "...And God Created Woman" (and even after, with the 1959 "Come Dance With Me"), her role was almost always a rebellious young bourgeois who trades a (usually) uptight, authoritarian father for another father figure, a loving, slightly older husband who knows just how much free rein to give her. She's not tamed, exactly, just leashed.

"...And God Created Woman" puts us on Bardot's side, the side of the sort of woman that movies, even when sympathetic, traditionally treated as a bad girl headed for trouble. At a town dance, we watch Bardot as she overhears the guy she's pinned all her romantic dreams on tell his buddy that a girl like her is only good for one night. But there's something unusual in the moment. Bardot is able to convey hurt without any indication that she feels cheapened. Leaving the dance in the red dress she put on for the occasion, she carries herself like a natural queen. (She often did. Her long unruly hair, puffed up and trailing down her back, might be her tiara and cape). And though Jurgens is given lines about how Bardot was made to destroy men, that's made to seem his own nonsense. The men in the movie generally behave like such clods they invite their own troubles.

Throughout "...And God Created Woman," the town prudes try to throw a figurative veil over Bardot. But they are more threatened by her than she ever is by them. With the wit of the true subversive, Vadim makes the movie's greatest affront to conventional morality the one that embraces traditional values. On the way home from the church wedding, Trintignant gets beaten up defending Bardot's honor when a local tough makes a remark about her. When he arrives at his mother's house for the wedding feast bloody and bruised, Bardot whisks her new husband upstairs to tend to his wounds and they wind up making love. Vadim describes what follows:

"It wasn't Brigitte's sunbathing in the nude that enraged 'decent' people. It was the scene where Brigitte makes love with her husband after the religious ceremony, while her parents and friends wait for her in the dining room. It was an amused Brigitte without complexes, appearing in her dressing gown, her lips puffy from lovemaking, picking a few apples and chicken legs to feed her lover -- for even though married she treated her husband like her lover and not her master. And the mother asking, 'How is he feeling?' and Brigitte's reply, 'Not bad.' And the mother, 'Why doesn't he come down? Does he need anything?' And Brigitte, 'I'm taking care of that.' She went to the staircase with her tray and, even though the sun was still in mid-sky, said goodnight to the guests."

The lovemaking scenes between Bardot and Trintignant, in which we don't see much more than her unbuttoning his shirt and proclaiming him very handsome, are the most erotic things in the movie. They have all the solemn energy and sudden giddiness of youthful sexual discovery. This is something that's still unusual in the movies: a sexualized view of marriage where, as Vadim said, the couple treats each other like lovers instead of spouses. And while the movie ends with Trintignant taking charge of his new wife, and her submitting (because, it's implied, he's learned to be a man), the last shots of them heading into the family home are subdued and ambiguous. You believe they love each other, you believe that they can be happy together; you don't believe this woman is going to stifle herself in the way that will earn her the respect of this tiny provincial town.

In real life Bardot didn't settle down. By the end of filming "...And God Created Woman," Bardot had left Vadim for her costar Trintignant. Bardot and Vadim worked on four more films together through 1973 and remained close until his death in 2000, when she paid him the supreme compliment of calling him "seduction itself," and saying of the men she married after him, "They were only husbands."

Their next collaboration, "The Night Heaven Fell" in 1958, falls into the stiffness that "...And God Created Woman" avoided. But there is something fascinating about the neuroses of Bardot's performance. Escaping into the Spanish countryside with the man (Stephen Boyd) who killed her abusive uncle, Bardot at one point cries, "We did it, Lamberto! We're nowhere!" It's an adolescent's dream of shutting the world out, the void as Valhalla, and it's affecting and more than a little scary.

Reading Vadim's memoirs allows you to see how much of Bardot's personality he worked into the characters she played for him. In "The Night Heaven Fell," Vadim seems to be capturing what he called, not entirely as a compliment, "her profoundly childlike nature ... an unquenchable thirst for love." Bardot is startling in "The Night Heaven Fell" because here we get the other side of the unconscious rebel, the perpetual adolescent making unreasonable demands on the world.

That's what links her to another perpetual adolescent who was her contemporary, James Dean. In the same year that "...And God Created Woman" opened, François Truffaut wrote an obituary for Dean that contains a list of qualities that could also describe the Bardot persona: "modesty, continual fantasizing, a moral purity not related to the prevailing morality but in fact stricter, the adolescent's eternal taste for experience, intoxication, pride, and the sorrow at feeling 'outside,' a simultaneous desire and refusal to be integrated into society, and finally acceptance and rejection of the world, such as it is."

"The Night Heaven Fell" is an anomaly in Bardot's performances; she usually played happy characters. The unhappiness she showed in it might have been close to the life she lived over the next few years. The picture of her painted by the press could be summed up by the idiot titles on the American trailer for her 1956 comedy "Naughty Girl": "Here She Is! The Rage of All Paris! That Chic Chick That's Causing the Sensation!" (If that isn't enough, there's an announcer who tells the audience to see the movie and "have the Frenchiest time of your life!") The reality was a series of unhappy marriages and love affairs, another suicide attempt on her 26th birthday, and a growing weariness of and hatred for the press.

The pleasure Bardot communicated as a performer often came across strongest in the '60s in the variety specials she did for French television, or in her pop singles like "La Madrague" or "Un jour comme un autre." Bardot had wanted to be a dancer early in her career, and a 1963 show offers her a chance to do a darling Charleston. Her legendary 1968 New Year's Day special features her and Serge Gainsbourg dueting on the ineffable "Bonnie and Clyde" and Bardot straddling a motorcycle in a leather minidress while singing "Harley Davidson," a segment resulting in a poster that graced a thousand dorm room walls.

The movie in which she made her greatest mark during the '60s has no happiness to be found, though it does have great beauty. Jean-Luc Godard's 1963 "Contempt," based on the superb Alberto Moravia novel, is an elegy for cinema seen through the prism of a marriage falling apart. The movie is stately, tragic, and almost unbearably wounding. Bardot plays Camille, whose screenwriter husband, Paul (Michel Piccoli), signs on to write the script for a film of "The Odyssey," to be directed by Fritz Lang (playing himself). But the real boss is the vulgar American producer Prokosch (Jack Palance). Because of one moment that Camille perceives as Paul trying to foist her on Prokosch to further his career, her love for her husband dies.

The heart of the film is a stunning 35-minute sequence between Bardot and Piccoli in their Rome apartment in which they argue, reconcile and wind up separated by that horrific distance that only people who love each other can share. There is a moment during their squabbling when Piccoli asks, tentatively, "You don't want to make love?" and Bardot, smiling, affectionately embraces him and says, "Listen to the jerk." His male insecurity prompts him to ask, "Is that a mocking smile or a tender smile?" and now, mocking him, she answers, "a tender smile."

The twists and turns of a marital argument are contained in those four lines. Godard retained Bardot's adolescent petulance here, and an adolescent's capacity for hurt. But he allowed her to add to it the depths to which an adult can feel hurt. Watching her tears you up.

Godard honors Bardot in this movie. He knew the entire world was looking at her, that directors were content to simply place her in front of their camera. When the camera regards Bardot in "Contempt," it sees a person and not a charming model. Godard and cinematographer Raoul Coutard observe Bardot (many of her scenes are wordless), allowing her time for the pain and betrayal and offended pride in her to come through.

After "Contempt," directors should have been looking for new ways to use Bardot. The movie should have been her ticket out of trash. It wasn't. She was back to being a charming model in the film that followed "Contempt," the unwatchable 1964 Italian spy spoof "A Ravishing Idiot" (which gave us the lunatic romantic pairing of Bardot and Anthony Perkins).

You have to search through the dreary likes of "Shalako" (1968), "Les femmes" (1969), "Les novices" (1970) or her final, sorry collaboration with Vadim, "Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman" (1973), for flashes of the joy Bardot transmitted in front of the camera. Bardot at one point said that of all the movies she made, only three or four were any good. She wasn't wrong, even if some of the bad ones (like the '50s comedies) are still enjoyable. Given the quality of the films she was making, you can't blame her for calling it quits in 1973.

But there is one gem between "Contempt" and that early retirement, and it's the movie I'd choose if I had to pick one as a keepsake of Brigitte Bardot's screen career.

In Louis Malle's 1965 "Viva Maria!" Bardot is at the peak of both her beauty and her comic talents. The press had expected sparks to fly between Bardot and her costar, Jeanne Moreau. There were none, and there are none onscreen. Moreau is fine (or as fine as you can be when your character falls in love with a Latin American revolutionary played by George Hamilton). There is more eloquence in Moreau's opacity, in that downturned mouth, than in perhaps any other similarly stoic star in the movies. But this is Bardot's movie.

The movie is a picaresque vaudeville set among a group of music-hall performers traveling in Latin America in the early years of the last century. Bardot plays the daughter of an Irish terrorist who, from childhood, has trained with her father to wreak war on the British. After the old man is killed detonating a bridge, Bardot hides out with the music-hall performers.

She becomes Moreau's new partner and soon Maria and Maria, as they're called, are sensations, packing into the music halls men who are eager to watch them strip down to their corsets while they sing of Paree. After the pair encounter a brutal landowner trying, with the collusion of the church, to keep his people in poverty, they become revolutionaries to boot. Overnight they go from dream girls to secular saints ("Ave Maria y Maria," their followers say -- the movie is deliciously anticlerical) leading the rebels to victory.

The movie's political sensibility is -- deliberately -- limited to a vague '60s notion of the oppressed vs. their oppressors. The tone fluctuates wildly, and in the second half the comedy doesn't always triumph over the "Viva la revolución!" material. But it's a bright, happy, colorful picture, magnificently shot by Henri Decae, and with moments of genuine comic magic. In the battles that marble the second half of the movie, the music-hall performers each bring their own talents to the good fight. The suave silver-haired magician sends his trained doves to drop grenades on opposing soldiers and strokes the birds tenderly when they return. A marksman shoots off the lit end of an officer's cigar so Bardot can use it to light the fuse of a bomb. In the loveliest moment, the strongman bends the bars of the cell where Hamilton is being held so Jeanne Moreau can slip in and spend the night with her lover. Seeing her nestle up to his bare chest, the strongman delicately bends the bars back; it's the only propriety he can offer the lovers.

Malle's specialty was charming us with things that would ordinarily shock us, and the opening sections are so deftly funny that we're laughing before we realize what we're laughing at. A little girl (who will grow up to be Bardot's Maria) gambols in a field kicking a ball of what looks like twine. It's detonator cord, and soon a British army barracks has blown up. The comedy comes from the juxtaposition of the child's innocence and the murderousness of her task.

That contrast buoys Bardot's performance. Her Maria can grab a rifle and shoot a bad guy, or toss a bomb into an squad of soldiers without blinking. But all the other experiences a girl of her age might have had are completely new to her, and she wastes no time in sampling them.

The look of suddenly enlightened innocence on Bardot's face has never been as funny or sublime as it is here. Taking her first sip of whiskey, she does what you might expect -- coughs and sputters and says, "So that's alcohol." Then she provides the capper that sends the joke bubbling skyward. Announcing solemnly, "I like alcohol," she sends the rest of her drink down the hatch. Hearing Moreau talk of the wonders of l'amour and having never known them herself, Bardot decides to rectify the situation, impulsively going off with three men after a performance. The next morning, she emerges from a carriage, mussed and disheveled, her dress torn, tenderly kisses each of her deflowerers, and walks past her gaping colleagues without a trace of shame to rejoin Moreau in their wagon where, plopping her legs on the table and hitching up her skirt, she announces, "I'm bushed!"

Malle, who had worked with Bardot before in the roman à clef of her stardom "Un vie privee," sees past all the fan magazine piffle of Bardot the sex kitten to the ravishingly funny and beautiful woman beneath. Bardot's beauty in this movie is like a great joke that is so open and fresh it can't be made to feel smutty or low. Malle is so attuned to her radiance that he even pulls off the trick of dressing Bardot in boy's clothes -- an ill-fitting summer suit, striped fisherman's jersey, cloth newsboy's cap hiding her hair -- and smudging her cheeks with grime and, in the process, making her look as beautiful as she has ever appeared onscreen.

To acknowledge that Bardot is turning 70 seems in some way a denial of cinema's ability to stop time, to freeze the images we love and thus turn them into our fantasy of eternity. It doesn't have to be our picture up onscreen to make all of us feel like Dorian Grays. We age; the people onscreen don't. I have loved Bardot now from childhood to middle age. So though I wish her a happy 70th, it's not the B.B. I love that's aging. It's me.

Shares