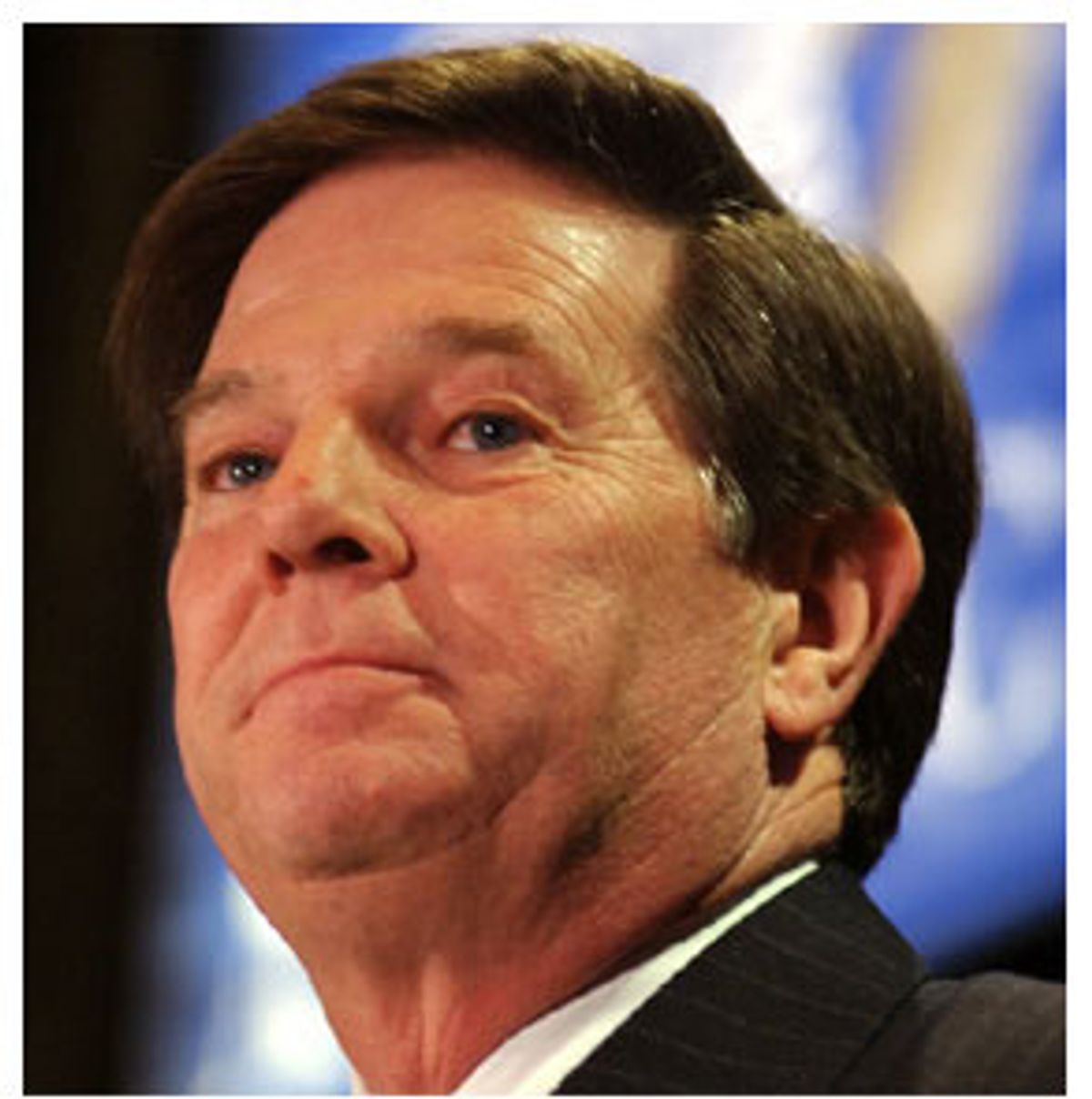

September was a bad month for House Majority Leader Tom DeLay of Texas. The year to come will likely be worse.

On Sept. 30, the House Ethics Committee issued a 62-page report rebuking DeLay for trading support for the congressional candidacy of the son of retiring Rep. Nick Smith, R-Mich., in exchange for Smith's vote on Bush's Medicare bill. "It is improper for a member to offer or link support for the personal interests of another member as part of a quid pro quo to achieve a legislative goal," the committee reported.

Back in 1996 DeLay got a walk in a fundraising scandal involving a front group known as Triad. That scandal cost a Texas businessman $400,000 in fines and resulted in an FBI investigation. But what the FBI turned up was never revealed because then-House Government Reform chairman Dan Burton, R-Ind., blocked attempts by the ranking Democrat on the Committee, Henry Waxman, D-Calif., to subpoena the FBI notes and files.

Now the story of the fundraising operation known as DeLay Inc. might not have such a happy ending. While he got a pass in Washington in the Triad affair, DeLay might be doing a perp walk in 2005 in Austin, where three of his fundraisers may be headed for the Big Rodeo and the corporations that wrote checks will be dragged before a jury on charges of making illegal political contributions. And there's more. Two of the majority leader's closest associates in Washington could soon be facing federal indictments for an Indian gaming scandal. Both have already been called to appear before a Senate committee, which held its first hearing on the Indian lobby fee scandal earlier this week.

Ronnie Earle, the district attorney who has held office for a quarter of a century in the Texas capital, indicted the three DeLay associates and eight corporations for soliciting and making illegal campaign contributions in September. DeLay's recent Texas dealings look like the Peter Cloeren story on a grand scale. More recently, DeLay and his Washington political operative Jim Ellis devised a much larger scheme to move money from corporations into the campaigns of Republican candidates for the Texas state House, which had been in Democratic hands for 130 years. With a Republican majority in the House, they eliminated the only obstacle stopping DeLay from presiding over the redrawing of the state's congressional district maps to create as many as seven seats likely to be won by Republicans.

Ellis, his Texas connection Jim Colyrando, and Warren Robold, a Washington fundraiser who worked for DeLay's political action committee, found corporate funding "vehicles" all over the country. The corporate donors were willing to invest in Texas state House races where they did little or no business in order to cultivate the favor of the majority leader. Donors were even assured that their contributions were "non-disclosable according to relevant state laws." And the contributions weren't disclosed in Texas. Texans for a Republican Majority (TRMPAC) listed corporate contributions only with the IRS.

There was one problem with the scheme. It's against the law to donate or spend corporate money on political campaigns in Texas. When the Austin district attorney realized what was going on he began an investigation. As the second grand jury that looked at the case concluded its extended term in mid-September, he handed down his indictments. DeLay didn't make the cut. But Earle seems to be employing what might be called a proctological prosecution strategy, a back-door approach that might yet lead to the majority leader himself.

One letter from a corporate donor points directly toward DeLay -- at least in its salutation, where a vice president of an Oklahoma natural gas company writes: "Dear Congressman DeLay: I am pleased to forward our contribution of $25,000 for the TRMPAC that we pledged at the June 2, 2002 fundraiser." The letter is an exhibit in a civil suit filed against TRMPAC. It's likely the D.A. will also have it and others like it. Williams Company Inc., the corporation that made the contribution, was one of the eight indicted in Austin.

Two weeks after DeLay's associates were indicted in Texas, the Senate Indian Affairs Committee began an investigation of two DeLay associates who billed six Indian tribes a staggering $66 million in lobbying fees, after promising tribal leaders that their proximity to DeLay equaled unparalleled influence in Washington. The story, broken by Shawn Martin at the quite literally backwater American Press in Lake Charles, La., less than a year ago, quickly found its way to the front page of the Washington Post.

Jack Abramoff, a member of DeLay's "kitchen cabinet," and DeLay's former press secretary Mike Scanlon billed their Indian clients twice as much as companies such as General Electric paid for outside lobbyists in the same time period. The tribes were paying the two Washington operatives -- who in private e-mails referred to the Indians as "troglodytes," "monkeys" and "moronic" -- to defend their casinos. Two U.S. attorneys in Washington and a federal grand jury are also looking into Abramoff and Scanlon, who are not only frequent fliers to gaming reservations around the country but also frequent contributors to Republican candidates and think tanks.

When the story broke, DeLay denounced his longtime friend Abramoff, telling reporters that Abramoff had never been on his payroll. He also warned anyone using his name to attract lobby clients to "stop it immediately." The warning came a little too late for tribal leaders slickered by Abramoff and Scanlon.

Everybody has lawyered up. Nobody's talking -- except when compelled to do so by state and federal prosecutors and the investigator that Sen. John McCain has assigned from the Senate Indian Affairs Committee to the case. And the upcoming 109th Congress is beginning to look like the longest two years in Tom DeLay's political life.

Shares