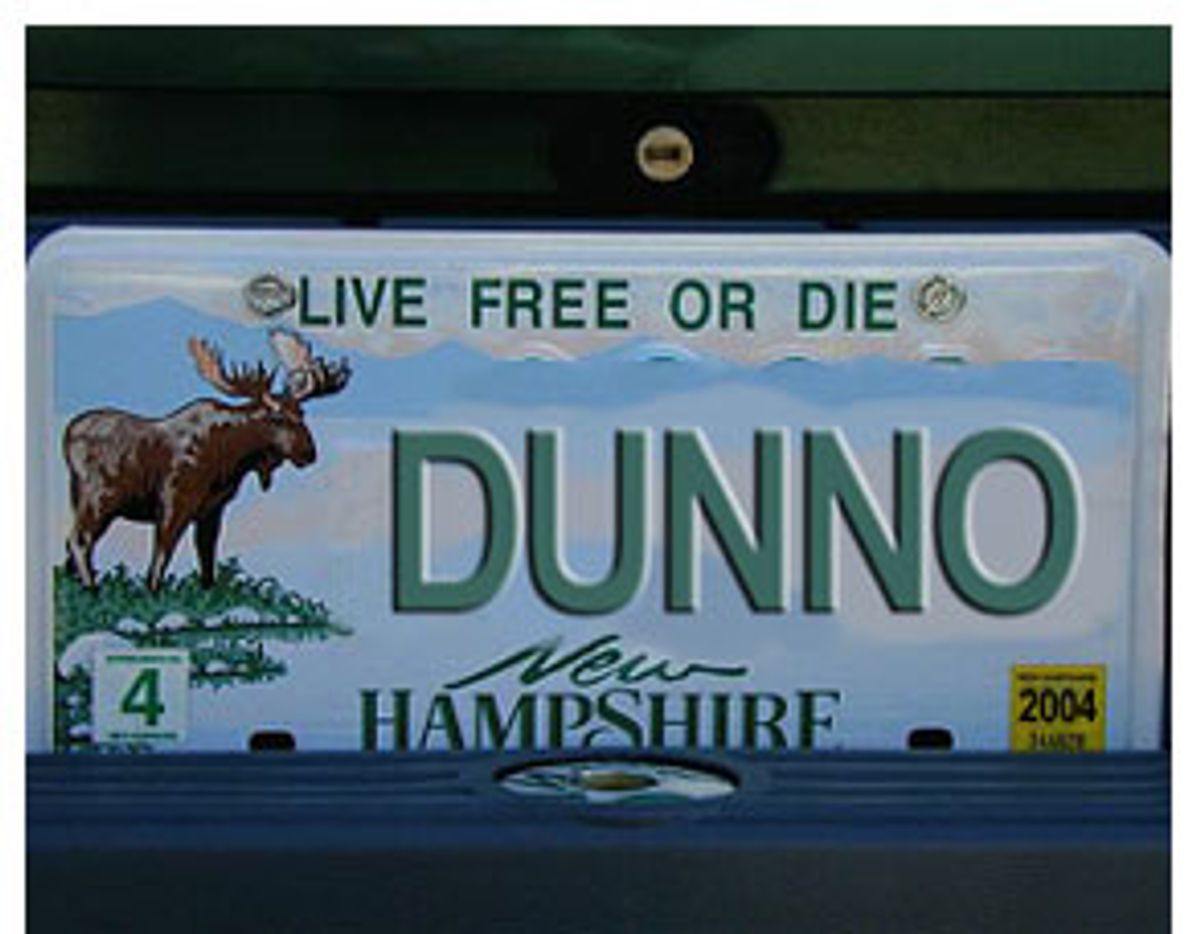

New Hampshire's official motto is "Live Free or Die." Visit the place in October of an election year, however, and you will quickly discover New Hampshire's unofficial motto. It is what the state's undecided voters declare almost every time they express their political views. "I've never been for a party," offered Connie, a Manchester homemaker, undecided voter, and mother of two sons in the military, saying the magic words on a recent Saturday afternoon. "I'm for the man." In a state where political independents outnumber both Democrats and Republicans, Connie's phrase, or a variation of it, deserves a place on New Hampshire license plates. But exactly which man the state's undecided voters will support -- John Kerry or George W. Bush -- could change the future of the country.

New Hampshire may be worth only four Electoral College votes, but it would have put Al Gore over the top in 2000 and might be decisive this year as well. Last time, Bush won by 7,211 votes, a 1 percent margin. It could be closer in 2004. Besides, if New Hampshire's voters tout their independence more than most, the state is otherwise a political cocktail containing the same ingredients that made the last presidential election so extraordinary: a deadlocked race, candidates scrapping for every last vote, Ralph Nader lurking in the background and, for an added kick, an ongoing GOP voter-suppression scandal. Which makes New Hampshire as good a place as any to ponder some questions: In the most ideologically polarized election in living memory, why are people still undecided? And who will they vote for?

To get a better sense, I accompanied canvassers from the independent group America Coming Together, or ACT, around New Hampshire on consecutive October weekends as they lobbied independent, undecided voters to support John Kerry. Most voters would only talk to the canvassers after prefacing their remarks with the standard New Hampshire declaration of political independence. "I'm not a Democrat or a Republican," said William, a self-employed man in Nashua leaning toward Bush. "I just vote for who I think is best."

"Democrats, Republicans, they all speak with forked tongues," explained Leonard, a retiree in Manchester theatrically pinching his nose for emphasis. "They're all full of baloney. They're all the same." He pinched his nose again. "I just go in there and hold my nose and pick a candidate." Still, since ACT's canvassers are instructed to ask voters which issues matter to them most, plenty of undecided voters are willing to talk politics despite their disdain for the major parties. The leading issues they mention are hardly surprising: Iraq, the economy and job market, and healthcare.

Perhaps the most encouraging trend for Democrats is that on the biggest issue of the day, few New Hampshire independents seem willing to give George W. Bush the benefit of the doubt. "I don't know why we're in Iraq," said Connie, the Manchester homemaker, talking while painting the front-porch railing on her house. "They should train the Iraqis and get our guys out. Are they there for oil? Saddam's a bad guy, but he was contained to his territory." One of her sons is a military chaplain and, she said, had told her about the terrible human toll the war was having on U.S. troops: "They're committing suicide. It's awful."

Kathy, a resident down the street, had a similar view. "After we went in and found nothing, I thought we were going to get our guys out of there. It's been too long. We're losing a lot of guys." Indeed, William, the self-employed man from Nashua, was the only voter I encountered who accepted whole cloth the Bush administration's blending of 9/11 and Iraq into a seamless campaign against terrorism. "I live down the street from a defense contractor," he explained. "Everything's a target. My kids just went to the mall." More typically, though, Iraq has gone badly enough to move likely Bush voters into the undecided column. "I don't know about the war," said Christopher, a contractor doing fireproofing work in Manchester. "I support the troops, though. But I don't know if I'd vote for Bush again."

This skepticism seems like good news for Kerry. The latest Concord Monitor poll puts Kerry ahead 49 percent to 45 percent for Bush, with Nader getting 2 percent and 4 percent undecided. But Kerry is winning the battle of independents, 52 percent to 40 percent. Then again, Kerry has to win independents to carry the state. Just 28.2 percent of the state's voters are Democrats, with 33.6 percent being Republicans and 38.2 percent undeclared.

Moreover, New Hampshire is not merely a contest for the remaining 5 percent of undecided, largely independent voters. The total number of voters in play is surely larger, since they can register at the polls on Election Day. And support for each candidate has fluctuated over time. From April through October, Kerry has ranged from 43 percent to 49 percent in the American Research Group poll, while Bush has ranged between 42 and 48 percent. In short, undecided voters do not consist of one steadily dwindling pool of citizens who gradually decide to back one candidate and firmly stick to that commitment. They can switch from one camp to the other, too.

"I keep going flip-flop, like Kerry," explained Connie, unintentionally demonstrating the power of Republican propaganda. Given her displeasure over Iraq, why is she not in the Kerry camp? Stem cell research, the very issue Kerry had been in New Hampshire touting just a few days earlier, at a newsmaking town hall event with Michael J. Fox. "I'm a Christian, and I'm against using matter like that." In fact, healthcare seems something less than a clear-cut winner for Kerry here. William, the Bush leaner from Nashua, had an instant rejoinder when ACT's canvassers started talking about the way Kerry's healthcare plan could help the middle class: "Yeah, but his wife is a billionaire." Leonard simply discounted the idea that healthcare was a significant problem: "They say 50 million people don't have health insurance. But if you go to the hospital, they won't turn you away."

Laura, a mother in Nashua, said healthcare was a crucial issue -- "There's a lot of people who don't have healthcare even if they're not old" -- but had not been persuaded by anything she had heard. "There's too much mudslinging. I turn on the TV, it's like watching children arguing. I just change the channel." These responses would likely dismay Kerry supporters, but seem to summarize the state of the race. Undecided voters are wary of Bush, but are unconvinced about Kerry and -- even after the first two presidential debates, when I visited New Hampshire homes with ACT -- not well-informed about his proposals.

All of which demonstrates the nature of the task ACT faces. "People's complaints here are a lot more progressive than their ideology," Graham Roth, ACT's Nashua field organizer, told me. Sure, New Hampshire residents will tell canvassers they want more affordable healthcare and education, and a tax policy favoring the middle class. But relatively few regard the Democrats as the party that shares those ideas. That is why, although Kerry supporters may think of ACT as a kind of giant vote-harvesting machine, it more closely resembles a group of farm laborers planting seeds. ACT makes repeated canvassing calls to independent voters, leaving literature if they are not home -- on Saturdays, perhaps a quarter of all targeted voters answer their doors -- and following up with mail. Gradually, they hope the care and feeding of potential voters will pay off, with undecideds seeing the Democratic candidate as sharing their own values.

Indeed, by emphasizing issues, ACT also hopes it can persuade voters -- even in New Hampshire -- to set aside their personal evaluations about the candidates and think about whose policies will help them. "Instead of being focused on who is John Kerry and who is George Bush, we can be focused on what the core values of the platform are," says Delacey Skinner, the deputy state director of ACT New Hampshire. "And the principles of each party really do matter, because they shape the way the whole country looks ... It's a challenge, but I feel we have almost more leverage in some ways."

In this sense, ACT's project is partly based on a kind of bet -- not recommended by every political scientist -- that you can sway voters by appealing to their rational (usually economic) self-interest. By having volunteers make the case for the candidate, the group is also trying to put a human face on these issues without necessarily invoking the politicians themselves, whom independent voters make such a point of disparaging. "So much of what people vote on in elections has to do with something that is sort of an ineffable quality, that is very difficult to articulate," acknowledges Skinner. But, she adds, "There are a lot of people who are just flat-out fed up and they're out there saying, 'I really don't like Bush, but I'm not so sure about Kerry.'" After all -- virtually by definition at this point in the campaign -- undecided voters have not yet made a final, gut-level decision about the candidates. So perhaps some issue-based persuasion by friendly fellow citizens is in order. Take Florence, a senior citizen living in downtown Nashua. "Bush has already shown he can't do the job," she said. What about Kerry? "I really don't know him. I can't say I don't like him, though." Florence appeared to be in failing health, and after a discussion with ACT's canvassers about healthcare, she seemed ready to vote for Kerry, on one condition: "I need a ride to the polls."

After watching ACT canvassers ring dozens and dozens of doorbells in Nashua and Manchester, however, the only time I saw them seal the deal on the spot was in their encounter with Florence. Undecided voters can be cagey. Some may be waiting to see how the race breaks at the end. "Independents love to vote for a winner," says Craig Downing, a former Republican member of the state Legislature who is now a government administrator and an independent supporter of Kerry. The key question for Kerry, Downing thinks, involves one basic dynamic left over from the Democratic primary: "Kerry was a lot of people's second choice. In New Hampshire, it will be, where did [Howard] Dean's voters go? Will they go out and vote?"

For that matter, it is a lingering question whether some former Dean supporters will vote, but with their sights set further to the left -- to Ralph Nader. The day after Kerry's stem cell town-hall meeting, I saw Nader speak at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. With the first words of his speech Nader dispelled any doubts about his current preoccupation: "This campaign has proved the political bigotry of the Democratic Party." Translation: Nader is unhappy the Democrats are competing hard against him in 2004. Of course, New Hampshire Democrats were unhappy to read news reports in August about Republicans helping the Nader campaign collect signatures for the state ballot. At the Durham event, some Democratic activists challenged Nader about this, during the question-and-answer session, but Nader -- typically -- ignored the question by defending the right of individual Republican donors to give money to his campaign.

In 2000, Nader received 22,198 votes, a solid 4 percent. (Other minor-party candidates received 1.2 percent of the vote.) Still, there is not a lot of energy around the Nader campaign at the moment. Attendance at the Durham event was about 120, including the Democrats and five students wearing Republican Party tags who left early to go to class. Every vote counts, but Nader's support will be markedly lower this year.

Another X-factor in the New Hampshire vote is the state's own GOP-sponsored voter-suppression scandal. In 2002, with a close Senate race at hand, Republican Party officials paid for continuous calls to be made to Democratic headquarters on Election Day, thus "jamming" the party's get-out-the-vote phone bank for 90 minutes. Chuck McGee, the former executive director of the state GOP, pled guilty in July to a felony charge in the case, which is still under investigation. The New England regional chair of the Bush campaign, Jim Tobin, stepped down last Friday after being referred to as a co-conspirator in new court filings last week. It's unlikely that fallout from the case will affect Bush, however, who has been a frequent visitor to New Hampshire this year -- Nashua is where he issued his August "challenge" to Kerry to further discuss Iraq -- and drew his biggest in-state audience in Manchester the day after the first presidential debate.

But with no right-wing equivalent of ACT operating in the state, the GOP will be dependent, here as elsewhere, on a high, high turnout of its base. Whether that is the right strategy or not will be apparent on Nov. 2. It is certainly simpler, however, than slowly trying to reach out to disaffected voters with no party identification and little feel for the candidates. Consider Kelly, a Manchester mother whose main issue is a potential military draft. "I have 16-, 17-, 18-year-olds. This draft thing, it's like, I don't think so." Is that enough to turn her against Bush? Not necessarily. She knows she will remain undecided until Election Day. Indeed, Kelly's description of her voting rationale would make a party operative or ACT volunteer tear some hair out, but is probably as candid an admission about the whole process as anyone can offer: "It depends on what's going through my head when I step in there."

Shares