Friday night brings to a conclusion the fiercest media battle of the presidential campaign, when 40 of the Sinclair Broadcast Group's 62 stations nationwide air a special program about the media and Vietnam War POWs. The show is likely to include generous portions of an anti-Kerry attack film, "Stolen Honor," that Sinclair executives had originally intended to air in its entirety just days before the election. In the face of lawsuits by stockholders, loss of advertising, questions about its abuse of the public airwaves and a falling stock price, however, Sinclair quickly cobbled together a revised program.

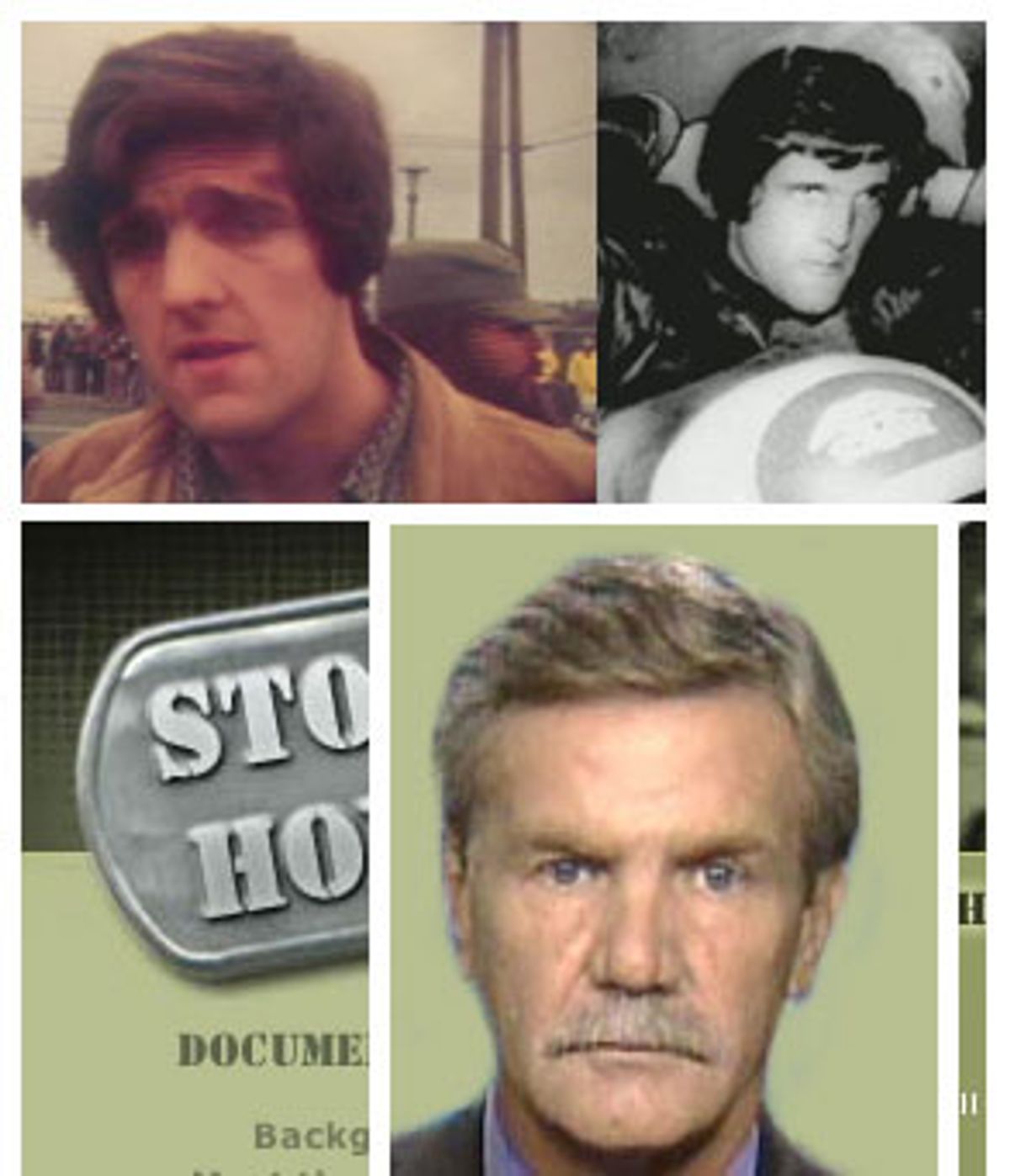

The controversy has thrust into the spotlight two men who both suffered dramatic, if long ago, professional blemishes that have suddenly become relevant. Their past behavior confirms their critics' worst suspicions -- that Sinclair executives manipulate the company's broadcast properties for their own gain, contrary to standard corporate practice, and that "Stolen Honor" is a misleading hit piece. The two men, who play prominent roles in Sinclair's Friday night telecast, are a conservative broadcaster who has not shied away from exploiting his television properties to serve his personal needs, and a television journalist with a right-wing agenda who once famously aired explosive allegations in a Vietnam veteran-related exposé that was later found to be completely false.

The first is David Smith, chairman and CEO of Sinclair. After being arrested with a prostitute during a sting in Baltimore, Md., in 1996, Smith, as part of his plea agreement, ordered his newsroom employees to produce a series of reports on a local drug counseling program, which counted toward Smith's court-ordered community service. "I really hated the way he handled our newsroom and what he expected his reporters to do after his arrest," LuAnne Canipe, a reporter who worked on air at Sinclair's flagship station, WBFF in Baltimore, from 1994 to 1998, told Salon.

The second is Carlton Sherwood, the producer of "Stolen Honor." Sherwood calls Sen. John Kerry a traitor for opposing the Vietnam War and concedes he never asked to interview Kerry for the documentary he made about him. This incident is not out of character for Sherwood, who has a history of erroneous reporting. In 1983, Sherwood leveled charges against the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. In a four-part series for a local Washington TV station, Sherwood suggested that the veterans responsible for creating the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall were misspending -- if not stealing -- donated money. One year later, when Sherwood's charges proved to be baseless, his former television station employer was forced to air an extraordinary retraction and donate $50,000 to the fund in order to fend off a lawsuit. "It was a hit piece," Bob Doubek, who served as project director for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, told Salon. "All of Sherwood's stuff was conjecture, smoke and mirrors."

Sinclair's unprecedented broadcast decision regarding "Stolen Honor," coming at the climax of one of the most heated presidential campaigns in modern times, and seen by many observers as blatantly unfair, ignited an equally unprecedented revolt. There have been widespread calls for advertising boycotts, formal complaints to the Federal Election Commission and the Federal Communications Commission, a shareholder lawsuit, a libel lawsuit and the threat of an insider-trading lawsuit.

On Tuesday, Sinclair moved to stop the bleeding, at least on Wall Street, by announcing that its stations would not air "Stolen Honor" in its entirety during prime time, but would instead run a hastily produced one-hour news special, "A POW Story: Politics, Pressure and the Media," which itself will feature portions of "Stolen Honor." Sherwood's film presents the emotional accounts of former POWs, a number of them not identified as active in Republican politics, who argue that Kerry's antiwar activities, not President Nixon's policies, helped extend the war and caused the men to be held captive for longer than they would have been otherwise.

At midweek Sinclair officials signaled that even they were unsure what the program would look like, so it's impossible to predict what the show's final content will be. But given Sinclair's stated goals of the program -- to address "allegations of media bias by media organizations that ignore or filter legitimate news" -- along with Sinclair's obvious Republican sympathies, "A POW Story" appears to be another blunt instrument with which to bash Kerry.

For weeks Sinclair executives have been pressing Kerry to sit for an interview on its stations and explain his decision to protest the war. Yet President Bush has never been urged to appear on Sinclair stations to defend his service, or lack of it, in the Texas Air National Guard.

That sort of implied quid pro quo (appear on our stations or else) is "insulting to the news-gathering process," says journalist Paul Alexander, who's also the director of this year's "Brothers in Arms," a widely acclaimed documentary about Kerry's Vietnam experience. "That's not how you gather news; that's how you blackmail people." But news gathering was never the point, according to former Sinclair reporter LuAnne Canipe. "David Smith doesn't care abut journalism," she says.

That became clear to her, Canipe says, during the summer of 1996, when Smith was arrested in Baltimore for picking up a prostitute who performed what police called an "unnatural and perverted sex act" on him as he drove on the highway in a company-owned Mercedes. Smith was convicted of a misdemeanor sex offense.

"It was all very humiliating as a journalist," says Canipe. "The next day we went out in a station vehicle and we stopped at a light. And a truck driver sees the station logo on the side of the car and starts making a sex gesture to us."

The work atmosphere at Sinclair following the CEO's arrest also deteriorated. "Let's just say the arrest of the CEO was part of a sexual atmosphere that trickled down to different levels in the company. There was an improper work environment. I think that because of what he did there was a feeling that everything was fair game," says Canipe, who says she chose to leave Sinclair in 1998. She says that she once complained to management about another Sinclair employee, who had engaged in audible phone sex inside a station conference room, but that no action was taken against the employee. A Sinclair spokesman did not return calls seeking comment.

Most upsetting to Canipe was the deal Smith struck with the Maryland state's attorney, which allowed him to perform his community service by having his station air reports on the Baltimore drug court. "A Baltimore judge called me up," she recalls. "He wasn't handling the case, but he called to tell me about the arrangement and asked me if I knew about it. The judge was outraged. He said, 'How can employees do community service for their boss?'"

Smith, she says, "had a script written up [acknowledging his arrest] and made the anchor read it for him on the air. I asked the anchor why she was reading it, and she said she didn't feel like she had any choice."

Questions about Sinclair executives' public behavior extend beyond Smith's prostitution arrest and the "Stolen Honor" controversy. Last week, WBAL-TV in Baltimore reported that Frederick Smith, David's brother and a Sinclair vice president, owns a Maryland trailer park that's being sued for discriminating against African-Americans. Over the past year Baltimore Neighborhoods Inc., a housing advocacy group, sent test applicants to Smith's property to inquire about possible rentals. A BNI representative told WBAL, "When the black person went in, they were told every time that nothing was available, regarding either a trailer or a slab to put the trailer on. On every occasion that a white person went in and [tried] to ask for the same availability of properties, they were given some listing of properties and more or less encouraged to apply."

Citing "blatant discrimination," BNI filed a lawsuit against Smith, alleging violations of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Smith's attorney declined to comment to WBAL for its report about the lawsuit.

Sherwood's career is also checkered by questionable professional behavior and squandered reputation. A former Marine and Vietnam vet, Sherwood won a Pulitzer Prize in 1980 for his work at Gannett investigating financial donations to an order of Catholic priests. He was then hired by WDVM in Washington (now WUSA), and on Nov. 7, 1983, one year after the Vietnam Memorial was dedicated, he began a four-part series called "Vietnam Memorial: A Broken Promise?" -- in which he "raised serious questions regarding the financial propriety" of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, a private organization that raised $9 million to build the wall. Sherwood reported that only $2.6 million had been spent and wanted to know where the rest of the money was.

Those connected with the fund saw a clear agenda behind Sherwood's reporting. "During the development of the memorial there were a group of veterans who didn't like it, and they raised a lot of objections," recalls Doubek. "They wanted something that would say the war was right. They wanted a memorial that was tall and white. They said the design looked like a wailing wall. Eventually we were able to outflank them."

Resentment lingered, however, and that anger came through in Sherwood's reports about the Memorial Fund's finances, says Doubek. "There was a clear agenda because the people Sherwood interviewed were the same people who tried to stop us from building the memorial." (In a sworn statement sent to WDVM on the eve of the series, one Vietnam vet claimed he had conversations with Sherwood in which the reporter referred to the memorial as the "liberal memorial" and a "black gash." Sherwood denied ever saying that.) Sherwood could not be reached for comment.

At the time, several Republican members of Congress, expressing their "great concern" over impropriety at the Memorial Fund, asked the General Accounting Office to examine its records. One of the key critics was Rep. Tom Ridge, R-Pa., who later became governor of Pennsylvania and is currently director of homeland security. "Ridge just hated the wall," recalls Doubek. During the Memorial Fund controversy, Sherwood and Ridge became friends. According to a former staffer to a Republican senator, Sherwood prompted Ridge and the other Republican congressmen to attack the Memorial Fund.

In the 1990s, Sherwood was hired to head up Pennsylvania's video production agency. Ridge introduced Sherwood to President Bush in the summer of 2001. Sherwood now says he has no ties to the Republican Party.

In its 1984 audit the GAO dismissed every charge raised by Sherwood. WDVM's subsequent retraction was dramatic and unequivocal. "To officially set the record straight," station news director Dave Pearce told viewers on the night of Nov. 7, 1984, "we would like to correct any impression left from our broadcasts last November that the Memorial Fund or its officers have done anything improper. We regret any harm that may have been caused to the Memorial Fund and its officers. The evidence indicates they performed a great public service."

He continued: "The GAO investigation turned up no evidence which supported the statement made in our series. In addition, our own internal investigation into the story has turned up no evidence to support the charges made during last year's reports."

Despite the station's public rejection of Sherwood's work, he stood by his reporting, telling a reporter at the time, "I do not apologize. I do not retract anything that was aired." A New York Times article in 1984 about Sherwood's newsroom fiasco was headlined "Reporter's Project Ruins His Career."

Now, with "Stolen Honor," he's been given another chance, thanks to David Smith and Sinclair.

Shares