Maximus has long since maxed out, and Achilles had his moment of triumph at the box office. So now Hollywood has turned to Alexander the Great, the king of Macedon, conqueror of the Persian Empire and founder of a new world order, who died in 323 B.C. at age 32, as the muse of not one but two blockbuster movies about him: Oliver Stone’s “Alexander,” starring Colin Farrell as the sexually adventurous, hard-drinking legend and Angelina Jolie as his mother, Olympias, is headed to theaters Nov. 24, and is generating Oscar buzz before it has even been seen. And Baz Luhrmann is polishing up the script for his “Alexander the Great,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio in the title role and Nicole Kidman as Olympias. (The project was pushed back because Luhrmann says he cares too much about it to be “drawn into a race” with Stone.)

What’s more, the 1956 film “Alexander the Great,” starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom, has just been released on DVD, National Geographic is releasing an Alexander the Great DVD on Nov. 2, and the History Channel will air an Alexander documentary on Nov. 7. Several new Alexander biographies have been published in the past few months. Libraries and museums have hopped on the bandwagon with exhibits looking at Alexander’s life and legend. There’s even a new video game that allows players to do battle as the great military leader.

What is it about this legendary — and notoriously brutal — leader, a man generally revered in the West and genuinely reviled in the East, that has so captivated our imaginations at this particular point in history? Why Alexander, why now? Salon asked Paul Cartledge, professor of Greek history and chairman of the classics faculty at Cambridge University. Cartledge is the author of “Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past,” but is not involved in any of the Alexander film projects.

What is motivating the sudden surge in interest in Alexander?

Well, one reason why there is “Alexander” and a whole slew of ancient world movies coming up is partly because of the success of “Gladiator.” Hollywood people had thought, “No, no money in it.” But actually now, using modern digital effects — as “Troy” recently did — you can show a thousand ships without having to build them all, which would cost you a few dollars. Even so, “Troy” was a $200 million movie, and Stone’s “Alexander” is $150 million, but of course it will probably make back much more than that.

And then the second reason for the surge is the situation in the Middle East. Afghanistan and now Iraq.

How does that figure in?

Well, Alexander died in Iraq. He went all the way up to what’s now Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and then he went into Pakistan via Afghanistan. He is in a way a Middle Eastern figure and so the issue of East-West, the culture clash or culture conflict, is very big. And some argue that Alexander was actually very good because he tried to reconcile East and West — on his terms, of course. Others say he was a terrible man because he slaughtered hundreds of thousands, including Indians and Persians and you name it. Some people estimate he killed, or among his opponents there were killed, three-quarters of a million people.

I tend to take a middle position that yes, he was out for himself to an important extent. He was very much the conqueror, and conquering is not always nice. But on the other hand, the effect of what he did in terms of the spread of Greek culture, which laid the groundwork for Western civilization, is undeniable.

He’s looked on very differently in the East than he is in the West.

If you take today a Zoroastrian or a Parsi or even just an Iranian, and you talk about Alexander the Great, they’ll tend to have a very negative view of him as a destroyer. He burned down the palace of the old Persian monarchs and Zoroastrians believe that he destroyed in the process a number of their sacred books.

Do you think the Alexander obsession could exacerbate tensions between East and West?

I imagine that the documentaries will be balanced and won’t give uniform praise of Alexander. On the other hand, it’s difficult for a movie, like Stone’s, not to in some way heroize him. I have seen the synopsis and it’s not entirely positive. Aspects of Alexander’s personality are criticized. There is even the suggestion that he was murdered by his own courtiers because they thought he was getting too big for his boots, that he was taking them into places they didn’t want to go, either ideologically or physically. And that’s actually based on some historical evidence, though most scholars think that he died of a fever, either typhus or malaria.

Is it true that Alexander thought of himself as a god?

It’s a big issue and unresolved. Many certainly think that he did think of himself as divine and did want to be worshipped generally. He certainly was worshipped, there’s no question about that, both by Greeks and by Egyptians and others. But did he order people to worship him as a god? That’s where the uncertainty lies.

Are there any lessons from Alexander that come to mind when you consider the war in Iraq?

Well, you have to immediately distinguish any modern leader who fights from well behind the front lines using the most modern technology and doesn’t actually see face-to-face combat. Alexander was wounded many, many times, once nearly fatally, and he always led his armies from the front. He was always right at the forefront in a pitched battle or a siege, so you can’t compare your commander in chief to him.

On the other hand, I think the general lesson is that if you’re going to go into a country such as Iraq, there’s a very different culture, and bringing your ideas, you’ve got a notion that you are superior in some way culturally, or can somehow teach other people to be as good as you are. You have to think of the consequences. Not just whether or not you can beat the enemy, and in this case overthrow a regime, but what happens then? What is the likely consequence?

What I think has happened in Iraq is that you got rid of Saddam and the Baath party and all his friends and relatives who held power. What’s left is what was there before Saddam — imams and tribal warlords. We’re not dealing with parliamentary democracy. You cannot imagine that a military solution is going to bring about a political aim. Alexander, on the other hand, I think, had a much better idea. Perhaps the most significant thing he did was that very early on, after beating the Persians, he appointed a very senior Persian who had previously been on the other side as one of his governors. He made him governor of Babylon, which was one of the most important provinces in the old Persian Empire, now Alexander’s empire. I think that was a key move.

What about Alexander’s bisexuality, which is something that these movies are going to be able to deal with in a way that, say, the Richard Burton version couldn’t?

I’ve read a bit of Stone’s script, and that’s not flinched from. At the time, it was entirely normal that a young boy would have a sexual relationship with a 25-year-old man, and then when he became 25, he would have a relationship with a teenage boy, so I think “bisexual” is not quite right because that implies that you have a notion as to what it means to be hetero- or homosexual. For them, there is sex, there is sexual activity with either members of your own sex or members of the opposite sex, but what matters is age more than anything else and social status. And Alexander was odd in this respect, not in having sex with another male, but in having sex with a eunuch.

We’re not given particular graphic descriptions of this, but the evidence, I think, is pretty clear that he was in an affectionate, emotional relationship with a Persian eunuch. When he met him, the boy was maybe in his teens still. He had previously been a beloved of the great king of Persia. Alexander took over not only the crown, but the king’s favorite eunuch.

Now, that I think is quite shocking in Greek and Macedonian terms, because they thought eunuchs were effeminate and that if you’re a man, you shouldn’t in any way be like a woman. They had a very sharp notion of what was masculine and what was feminine, and the notion that Alexander would have a probably sexual, certainly emotionally affectionate relationship with a non-Greek eunuch was quite shocking.

On the other hand, what’s not in itself shocking, but is interesting is that he married three times, and each wife was Oriental. He never married a Greek or a Macedonian woman, which is, I think, quite remarkable.

Why do you think that happened?

It’s hard to understand. At the time that he would normally have married, 25, 26, he was in the thick of it, moving from Central Asia, in Iran, Iraq, he was fighting major battles, winning, so in a way, he didn’t have time.

What do you think of the casting for the Stone and the Luhrmann films?

There’s one absurdity, which is to have Angelina Jolie playing Olympias and she’s [nearly the same age ] as the actor who’s playing her son, Colin Farrell [Jolie is 29; Farrell, 28]. She should be at least 15 and maybe 18 years older. Nicole Kidman, who was cast in the Baz Luhrmann movie as Olympias to Leonardo DiCaprio, is at least older [37 to 29] than Leonardo DiCaprio. But, I mean, that’s a nonsense, frankly.

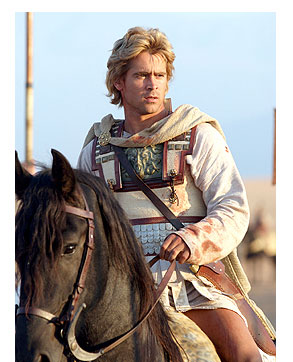

Otherwise, Colin Farrell is a quite interesting choice because Ireland as compared to Britain is sort of the wild Celtic fringe. Macedonia in relation to Greece to the south, it was thought of something like the wild and woolly fringe to the Greek world. And he has a reputation, which he cultivates, as sort of a hell raiser, and there is a bit of Alexander that is extremely hell raising and excessive. You know, he drank too much and he did probably kill too much. He was excessively cruel on certain occasions. He killed one of his best comrades when he was blind drunk in one notorious instance.

Farrell has said that the role was tremendously emotionally challenging for him (“It drove me a bit crazy. I just felt very lonely and very sad, that [Alexander] never got to a place of comfort, a place of joy, a place where he ever felt like he was achieving enough”), and DiCaprio said, “his legend is one of the most compelling stories in human history.” What makes Alexander so appealing for actors?

In a way, he’s a sort of an action man incarnate, and he was good-looking and had this amazing charisma. But what Farrell says is actually, I think, very perceptive, that in order to be a great king, you have to be somewhat lonely. You might confide in one person, and he did indeed confide in his best mate Hephaestion, with whom he probably had had a sexual relationship in their earlier days, and he promoted Hephaestion to his No. 2, therefore he could talk to him. But the problem was that Hephaestion seems to have been a sort of yes man. He doesn’t seem to have ever resisted anything that Alexander wanted to do, never told him, “No, you mustn’t do that.” And what Alexander needed really was a sort of reality check, which I think is what powerful, especially autocratic leaders tend not to have. They lose touch a bit, and they get lonely. And the loneliness of power is indeed a phrase that applies very much to Alexander.

What about Alexander’s relationship with Aristotle, his tutor?

That’s rather hard to pin down. On the one hand, he never lost touch with him after he was taught by him, from the age of 13. Alexander certainly was interested in botany and in medicine, and Aristotle was the son of a doctor and was particularly interested in medicine and zoology and botany. I think Alexander picked those up from him.

On the other hand, if Aristotle had been asked was Alexander his ideal monarch, I think he would have had to say no, because he contravened the most fundamental of all Aristotle’s rules, which is the golden mean: nothing in excess. I think Alexander was too ambitious. He did not control his temper adequately. His ambitions were too big, too total. And I think Aristotle if he’d had the chance to have a quiet word with him, he’d have said, come on, rein yourself in.