All of the conventions of the showbiz bio are in place in "Ray": the early tragedy that both spurs and haunts the hero; the chance meetings that, as in Dickens, later prove fortuitous; the exhilaration and shock that the hero's unique talents provoke; the personal turmoil that, in the genre, is always attendant upon professional success; the downward spiral that, in this case at least, presages redemption; even the montage of neon signs sliding across the screen to denote new cities, new clubs.

And yet any viewers who look at "Ray" and see only clichés are declaring themselves hopelessly lost to the real achievement of this picture, which is nothing less than a statement of faith in the inclusiveness of American culture. A movie bio of Ray Charles must be equal to the bigness of the man and the bigness of his vision of American music, and that's the crucial test that "Ray" passes. Ray Charles would not have been able to even imagine encompassing so much of the music he loved if he did not believe that a blind black man could make a place for himself in the America of the '40s and '50s, could transcend the barriers that defined what that place was.

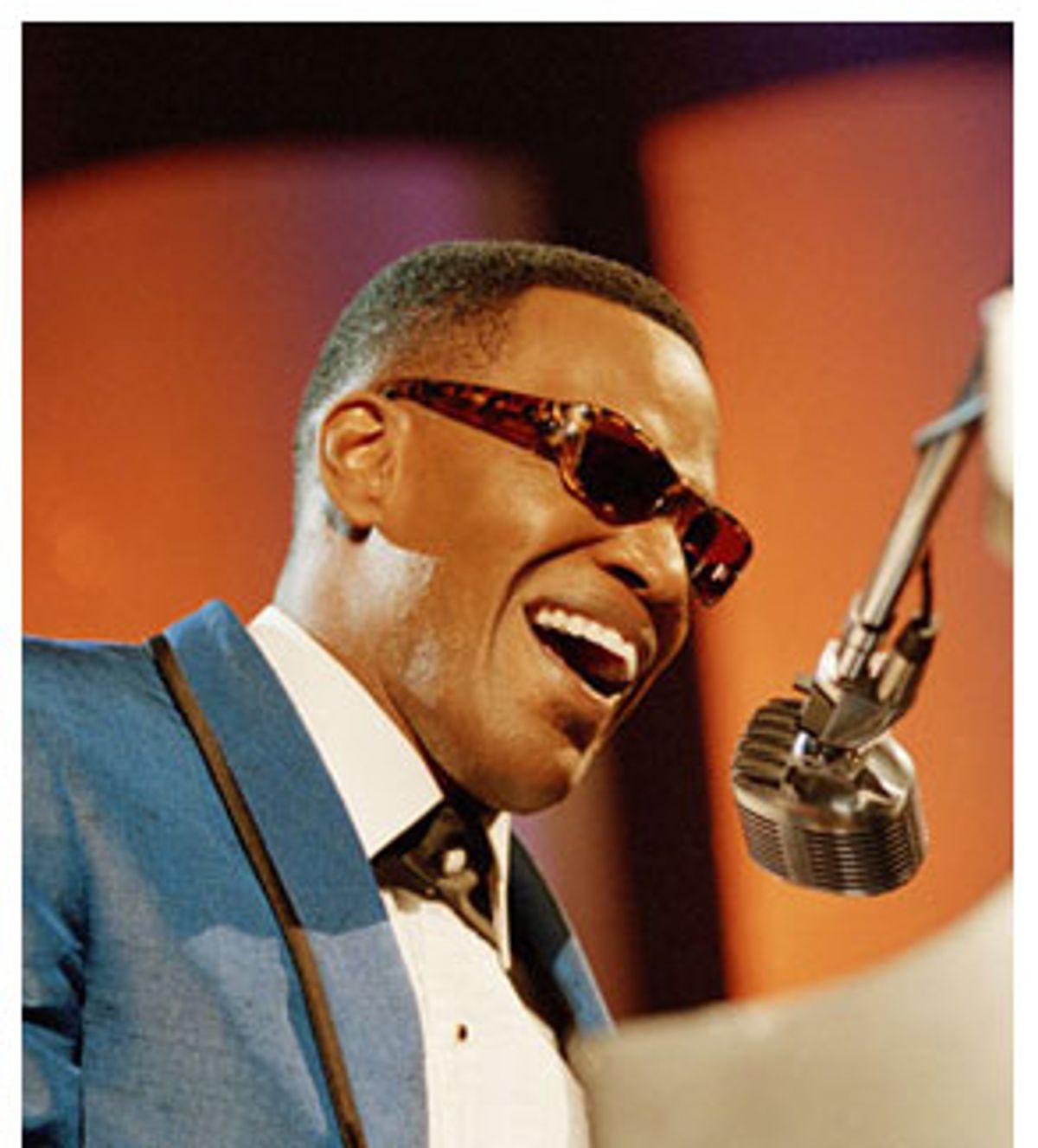

The rock-solid confidence that made Charles' achievement possible is what underlies Jamie Foxx's magnificent performance. The same confidence is visible on the faces we see in the black clubs Ray plays. Killingly sharp in their dresses and suits, availing themselves of the sophisticated night-life pleasures that once belonged only to whites, these people are separate (for now) but certainly anyone's equal in glamour, sexiness and hipness. Theirs are faces that, as Stanley Crouch wrote of the African-American faces in the work of Pittsburgh photographer Charles "Teenie" Harris, "speak of something so far the other side of alienation that all narrow images of these people -- or any people -- are called to the carpet."

The work that director Taylor Hackford does in "Ray" reveals its own confidence and ambition. Hackford's career has been marked by his wish to revive the well-crafted studio style of the '40s and '50s, but with a few exceptions ("Dolores Claiborne," some of "Everybody's All-American") it hasn't clicked. Here his work feels caught up in the joy of responding to the most challenging subject he has ever tackled. This is conventional filmmaking, but at its best, as in the miraculous scene where the young Ray (played by the remarkable child actor C.J. Sanders) first uses his sense of hearing to find his way around the shack he shares with his mother, the film has the direct, overwhelming emotion that brings us to the movies, and the peculiarly American-movie lyricism that is a marriage of commercial savvy and the instincts of craft.

It is exactly the old-fashioned quality of "Ray" that makes it so remarkable. Almost all of the most-praised American pictures this year have been catered to small segments of the audience. That's not always a bad thing. Sometimes it's the only way good work can get done. But this year, there has been something equally depressing about a good movie like "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" as about a bad one like "Sideways," and that is the preciousness they both share. They communicate no belief in movies as a communal experience, not even the regret of people who want to work that way but, by temperament, can't.

"Ray" has been made on the faith that a mass audience exists for something other than car crashes and adolescent japes. Cinematographer Pawel Edelman has given the film a rich, shadowed, dusky look. In the flashbacks to rural Florida, the red dirt and green grass are especially vivid. We're seeing Ray's childhood home as it has intensified in his memories of sight.

There are flaws and minor letdowns throughout: scenes that betray a crudity of approach; characters who aren't given their due; the showy cold-turkey where Ray kicks heroin; the sentimentality of the "redemption" scene; the cheap, rushed feeling of the closing montage covering the final decades of Charles' career. The faults are not invisible when you're watching the movie, but lingering on them is nitpicking. What "Ray" does right, combined with its generosity of spirit, makes it the most satisfying American movie of the year.

The arc of the story takes Ray Charles from the time he left Florida for Seattle in the late '40s to his cleanup following a Boston arrest for heroin in 1966. We see, in flashback, the 6-year-old Ray losing his sight to glaucoma after the trauma of watching his little brother drown in a washtub. We see his gigs in Seattle and the early recording sessions where he buried his own style beneath a pleasing mimicry of Nat King Cole. We see Ray on tour getting his first taste of heroin, an affair that would continue for the next 17 years.

We see his encounter with Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun (Curtis Armstrong), who signed him to the label, and the sessions at which Ertegun and the great producer Jerry Wexler (Richard Schiff) prodded him to find his own sound. We see the shocked reaction his melding of gospel and R&B provoked in the black community ("He's crying, sanctified," said blues singer Big Bill Broonzy at the time). We see him courting B (Kerry Washington), the Houston gospel singer he later married, and his longtime on-the-road affair with Margie Hendricks (Regina King), the Raelet who contributed to furious duets with Charles on numbers like "(Night Time Is) The Right Time." We see him leaving Atlantic for ABC-Paramount Records, where he had unprecedented control over his music and for which he was labeled a "sellout" for moving beyond the boundaries of R&B.

Despite the pancaking of years that's inevitable in all movie bios, and despite patches of evasiveness -- ignoring Ray's eventual divorce from B, for instance, in order to make it look like they stayed together -- James L. White's screenplay is hardly a whitewash. The film is skimpy on some subjects, and on others it doesn't match the startling candor of Charles' autobiography, "Brother Ray" (co-written with David Ritz and just reissued with Ritz's new afterword). Here, for instance, is Charles on the civil rights movement: "We had been hearing this bullshit about a Constitution and a Bill of Rights. Now it was time to test the waters to see if the words applied to us as well as the folk with the power and the money."

The film is much more forthcoming about the volatility of Ray's affair with Hendricks and her collapse into alcoholism. And the filmmakers make no attempt to hide that Charles could be a hard man to work for. In the scene where Ray fires a longtime employee for stealing, Foxx plays Ray as doubly remote, hiding behind his dark glasses and his office desk, and the effect is frighteningly cold.

But the real story here is the story of the music, and on that subject, "Ray" gets everything right. By making virtually the first thing Ray plays in the movie a country and western tune, the filmmakers, from the start, clearly understand that Ray Charles' music is about crossing barriers -- musical, cultural, racial. That means that by the time Ray has left Atlantic and is recording with strings and choruses of backup singers, releasing entire albums of country tunes (the first was 1962's seminal "Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music"), the movie has made us understand that the lush sound we're hearing is not the sellout or compromise that Charles' post-Atlantic career still represents to some music geeks, but where his music was headed all along. Almost all great commercial movies operate from this same place -- a place where an artist trusts that he can find a vehicle for his deepest, most personal expression that will also be emotionally accessible to a wide audience.

The recording and performance scenes in the movie are a joy, beautifully layered sequences that make us feel the music as the interplay of personalities, the vagaries of chance and Ray's push to realize the sound he heard in his head. Superbly edited by Paul Hirsch, the sequences manage to break the music down to each performer's contribution and create a rhythm that unifies the disparate bits into a cohesive whole.

Perhaps the reason so few songs are allowed to play out in their entirety is that Hackford wanted to keep things moving. But there are moments -- such as the terrific scene where Ray comes up with "What'd I Say" as a vamp to pad out a show to the contracted length -- when the music is swinging, when Ray and the band are in perfect sync, overjoyed and surprised by the sound they're making, when the faces of the crowd are shining, that you could happily watch for much longer than they are allowed to go on. And Hackford and White complicate our response by not allowing us to forget what fueled at least some of this energy. In one scene, Ertegun and Wexler, in the midst of recording Ray, notice he's developed the full-blown junkie twitch. "But just listen to him," Wexler says. It's one of those appalling and completely sympathetic moments when someone blurts out the unsayable: What if he doesn't sound as good without the junk?

Ray Charles' music didn't depend on dope, and in an odd way Jamie Foxx's performance reminds us that we knew that all along. Those strange bodily movements of Charles', the way his right leg dusted the floor by the side of his piano bench as if looking for purchase, the way he embraced himself in response to applause as if he were hugging the audience to him, the way he held his head back and moved his torso from side to side as if he were about to levitate, are less drug-induced than the body language of a man to whom sound was the most concrete thing: Foxx's Ray undulates to caress the currents of sound rising around him, like musical notes in a cartoon.

For the stature Charles attained in both life and death as a musical genius and a national treasure, we are not so far advanced that we can take as an everyday occurrence a big Hollywood movie that confirms his achievements. It was only a drop in the bucket ago that "What'd I Say" was banned on the radio, its singer excoriated as one of the savages depraving white American youth.

Similarly, American movies have not advanced so far that we can take for granted a big Hollywood movie in which almost all the roles are played by black actors. Just a few months ago Stanley Kauffmann gave Jamie Foxx the back-of-the-bus treatment by not even naming him in his New Republic review of "Collateral" -- though Foxx is the costar of the movie. And the hero.

Maybe Kauffmann can see fit to mention his name this time. "Ray" is the movie that finally allows Foxx the full flower of his talent. His Ray Charles is such a fully lived-in performance that any questions of imitation vanish. You don't watch him thinking, "I can't believe how close he is to Ray Charles." You watch him as if you're watching Ray Charles. It's Charles' own recordings we hear in the musical numbers, but Foxx's imitation of Charles' speaking voice is uncanny. It begins as a sort of stutter, then words start to come out in little husks, almost without breath. The words gather speed and bubble out -- higher than you'd expect but gently, as if he were half speaking to himself -- before slowing to the insinuating honey drip with which he draws sentences to a close.

It's the voice of a lover, a put-on artist, a player who holds his cards close to the vest. Throughout, Foxx gives the impression of a man whose blindness lets him live -- at least in part -- in his head. His Ray is calculating the distance between where he is and where he wants to be. Foxx flashes Ray's famous smile as the smile of a charmer who knows exactly how to get what he wants, and he uses his voice as if it contained invisible feelers that dart out to take the measure of a situation and retract to feed him information. Those feelers seem to slide around the women in Ray's life, drawing them to him, before he's laid a finger on them.

Foxx plays Ray so that his blindness becomes an emblem of a separateness that already surrounds him like an aura. (Foxx had prosthetic eyelids glued over his own so that, even though he has dark glasses for most of the movie, he acted most of it blind. It's a major miscalculation when Hackford shows us Ray with his eyes open in a dream sequence; for a few seconds the performance goes poof.) The flashes of anguish that suddenly overtake Ray are a cruelty he has to endure alone -- at least until he convinces himself that heroin will ease their visitations.

It's this private, cloistered quality that makes the humor and seductiveness in Foxx's performance so vivid, and that makes the blazing desire to connect that comes through in Ray's music so powerful.

Great as Foxx is, he's not the whole show. One of the joys of "Ray" is that it showcases black actors we get to see much too seldom. Kerry Washington as Ray's wife, B, has one of the most open faces in the movies. And Regina King brings her performance a hard sadness she has not shown before. Aunjanue Ellis has a brittle melancholy as Mary Jane, a backup singer Ray loves and leaves, and the newcomer Sharon Warren has a fierce presence as Ray's mother, Aretha, young, alone and faced with a job that would break any mother's heart: toughening up your handicapped child to prepare him for the world. As members of Ray's band and entourage, there's good character work from sad-faced Clifton Powell, Bokeem Woodbine and the fine actor Harry Lennix.

As the men who guide Ray's music and career, a trio of white actors bring their roles the sly humor of inadvertent hipsters: Richard Schiff as Jerry Wexler; David Krumholtz, whose sleepy affect hides quick comic timing, as the manager who finds his soul mate in the business-savvy Ray; and Curtis Armstrong (best known for the "Revenge of the Nerds" movies) as Ahmet Ertegun. Armstrong's is an immediately ingratiating performance. He plays Ertegun as a music-loving nebbish both amused to find himself head of soul central, and serious about being a good steward of R&B.

As a richly entertaining movie that manages to do justice to a giant figure in American music, while still allowing us to see him as a human being, "Ray" would be welcome in any year. Opening this weekend, it feels even more precious. It would be the easiest thing for many of us to feel alienated from America right now, to see our current government as the sum total of our country. Most of us will never face anything like the combination of personal hardships and legalized prejudice Ray Charles faced, and because of that "Ray" offers hope.

At a time when we need to be reminded of it, "Ray" says that the ignorance America periodically embraces cannot erode the richness, the omnivorous inclusiveness of our culture. "Ray" is about the beauty that lies in blurring the strains of that culture. It's about how one man's musical vision blended separate voices into one voice that let us hear echoes of ourselves. "Ray" celebrates a man who earned the right to make the simplest and most profound declaration: I hear America singing.

Shares