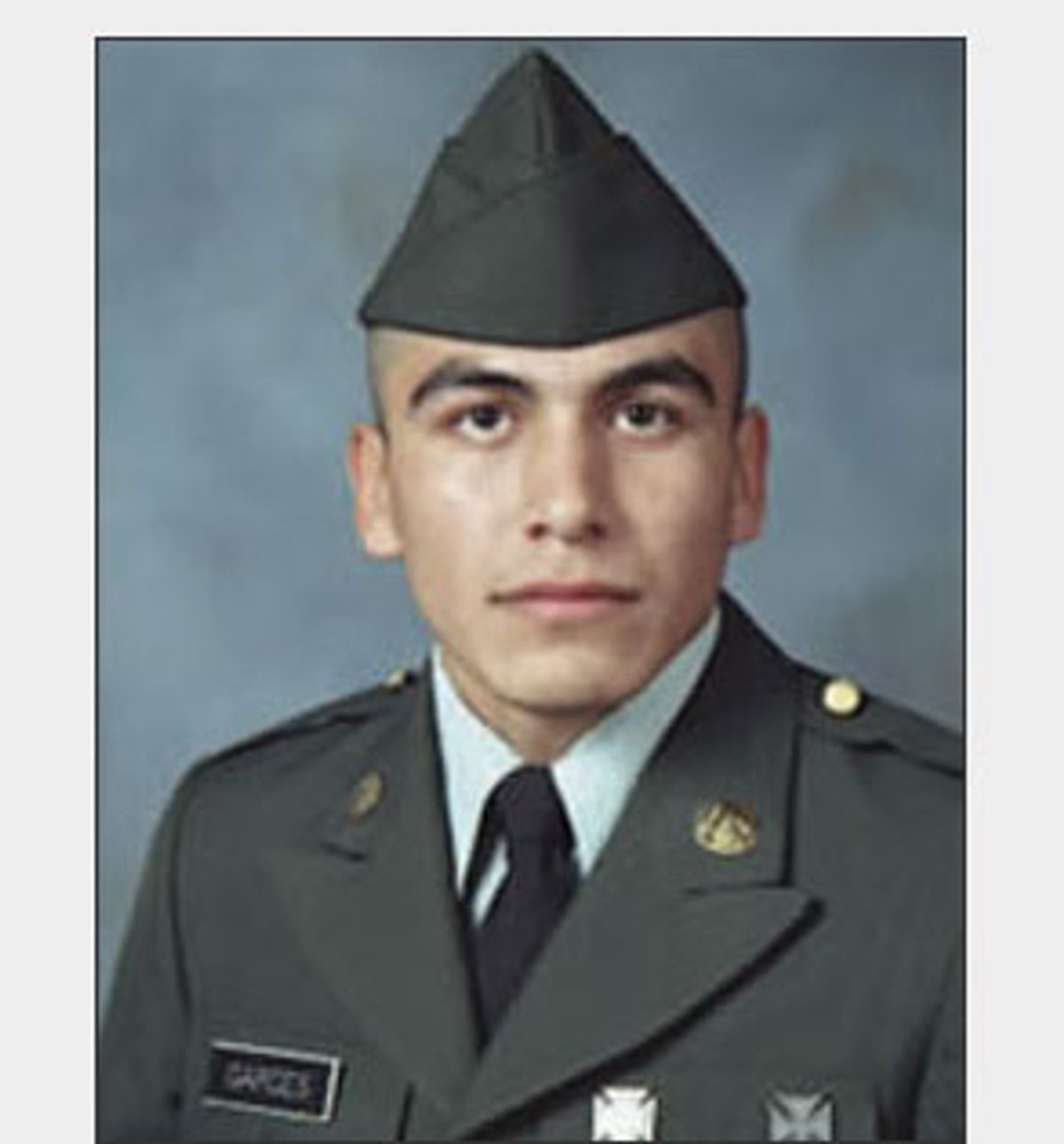

The death of a young Texas Guardsman on Sept. 6 went largely untold by the national press. But the story of Spc. Tomas Garces could have provided a poignant footnote to the "60 Minutes" interview that aired two days later with a well-known powerbroker from the Lone Star state.

As you may recall, former Texas House Speaker and Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes recounted how he had helped George W. Bush and other fortunate sons of the well-connected secure prized slots in the National Guard to duck the draft during the Vietnam era. By the time the TV story played to millions of households, Garces' parents, Sonia and Rafael Garces, were overcome with grief and making funeral arrangements for their son, the second of five children. That he was the Texas Guard's first combat casualty since World War II meant little to them.

On Sept. 9, as Bush supporters scrambled to defend the president's honor, local officials in Garces' tiny hometown of Weslaco issued a proclamation honoring the fallen soldier; they ordered flags lowered and established a bank account to help the family pay for funeral expenses. This was the second war casualty to hit Weslaco in as many weeks. Marine Sgt. Juan Calderon Jr. was killed in action the month before, leaving behind an economically destitute family. "The first casualty set the standard for what we would do to help the family," said City Manager Anthony Covacevich. "We learned a lot from that first one."

What the country could learn is that the commander in chief who joined the Texas Guard to escape combat (and went on to shirk routine physicals and weekend drills) more than two decades ago is relying on a very different Guard to fight his protracted war in Iraq today. Now the Texas Guard is mostly men and women like Garces who come from families of modest means. They are certainly not the sons of Texas powerbrokers who comprised the "champagne unit" of Bush's 147th Air Guard in Houston.

As it now happens, the 147th has seen the deployment of some of its members to Iraq and Afghanistan. Its Air Wing division has been on duty since 9/11, patrolling the air space in and around Houston and the Gulf Coast. Indeed, the last of the bubbles in this champagne unit popped and fizzled when the draft ended in 1972. "Champagne unit?" asks unit spokesman Lt. Col. Karl Schmidt, sounding genuinely surprised. "I had never heard of that until you mentioned it. Beer would be more like it."

Garces, who was killed when an improvised roadside bomb detonated as he rode in a convoy outside of Baghdad, will not be the last Texas Guard member to die in combat. In Texas, the National Guard has rotated more than 4,000 troops in and out of Iraq and Afghanistan and is training another 3,000 or so members for deployment over the next two or three months.

Many of these recruits hail from the Rio Grande Valley, a four-county area of small towns and dusty colonias in the southernmost tip of Texas, near the Mexican border. The Valley, as it is called, is one of the poorest regions of the country and the highest in the state for children without health insurance.

As a one-and-a-half-term governor in the 1990s, George W. Bush enjoyed a fair amount of support among the largely Democratic Valley Hispanics, even in his first run against the wildly popular incumbent, Ann Richards. As a Republican, he gained the most ground with Valley voters during his 1998 reelection bid -- before he tried to shaft them on health care. In the 1999 legislative session, Bush fought a bipartisan bill to grant low-cost health care coverage to 500,000 children. But state lawmakers stood their ground and won.

One of Bush's biggest accomplishments as governor -- tax breaks -- was of no use to Garces and his family, who lived on the outskirts of Weslaco, a city of 29,000 whose largest employer, apart from the school district and the local hospital, is Wal-Mart. "He comes from a very poor family," says the Rev. Lucy Martinez, who pastors the Pentecostal church that Garces attended in the colonia of Llano Grande. "His main purpose for joining the National Guard was to help his family financially," she says. Garces grew up in this church and provided part of its musical lineup as part of a Christian band that included his father and two brothers. Garces played bass.

A strapping high school wrestling champion, Garces dreamed of using the Guard's tuition benefits to attend college and become a wrestling coach. At the time, the topic of war had not yet grown to a point of national debate and so the Garces family assumed that Tomas would be able to stay close to home while assisting victims of hurricanes and floods, according to his younger brother Ruben.

Very quickly, though, Garces went from "weekend warrior" to fulltime soldier. By late 2003, he was ordered into active duty and spent two months training at Fort Bliss before deployment to Iraq. He arrived in February. His unit, the 1836th Transportation Company, delivered equipment and supplies to ground troops throughout the battle zone. On the day he was killed, Garces' convoy was transporting equipment and supplies from a port in Kuwait to the 2nd Infantry Division in Iraq.

The platoon leader in charge of the convoy, 1st Lt. Josh Hartwick, told the Daily Press of Newport News, Va., that Garces was manning a .50-caliber machine gun atop one of the lead gun trucks protecting the convoy. He was the only casualty in the explosion. The soldiers paid their respects at a memorial the following Sunday, the newspaper article said, offering a final salute to a monument consisting of Garces' M-16, his dog tags, his helmet and a pair of freshly cleaned boots.

The National Guard's tuition benefits have always been a big draw for kids coming out of the Valley, where agriculture -- cotton, mostly, along with citrus fruits and juicy melons -- is still one of the leading industries. In recent years, the area has also provided fertile ground for recruitment drives, due in part to the Guard's well-established presence with an Armory division. It is uncertain how many of the Valley's men and women have signed up for the Guard since 9/11, but the numbers are great enough to have prompted state Rep. Aaron Pena of nearby Edinburg to propose legislation in 2003 to ensure that Guard members get a fair shake while serving their country. The bill would have prevented Guard members from losing civilian jobs while on active duty. Yet the bill never made it out of a GOP-controlled House committee.

Economics alone doesn't drive south Texas men and women into the National Guard. Sgt. Michael Espinoza of Mission, Texas, a Rio Grande town known for its lush grapefruit crops, has a different explanation. "From what I hear, the Valley is one of the highest recruiting areas in Texas, and I think one of the main reasons is because we're very patriotic," he says. At 23, Espinoza is already a seasoned Guardsman with four years of service under his belt, including a six-month tour in Iraq, where he helped turn a 25-bed hospital into a 200-bed hospital for injured troops and prisoners of war. He worked in the admissions office across from the emergency room.

"You can imagine the chaos," he says. "As soon as people found out it was a field hospital, they'd start bringing in their injured kids and aunts and uncles, and what have you." This close-up view of the tolls of battle was jarring at first, Espinoza says. "I'm the type of person to just pick up the ball and run with it. That's the way you keep going. Stay alert, stay alive."

For her part, Valley-grown Sgt. Irasemi Rodriguez would not be as gung-ho the next time around if called to duty. As a mother of two, she is still haunted by the memories of tiny Iraqi children, no more than 3 years old, she reckons, barefooted and begging for food along the road. "It breaks your heart," she says. "From what I see on TV and from what I hear, I know it's very bad over there right now. And to tell you the truth, I wouldn't want to go back. I'm just hoping the unit I'm in doesn't have to go."

Even with the Pentagon's stop-loss program, a policy that prevents troops from leaving the military once their contracted time is up, there is no guarantee that the Texas Guard will continue turning out bumper crops of new recruits. The Rio Grande Valley's enthusiasm could also be tapping out at some point, considering it has already bid farewell to 10 servicemen in various branches who have died in Iraq. After the Garces casualty, things have gotten so bad that even relatively conservative community boosters like the Weslaco mayor and the school superintendent called for an end to the war, as did one of the local newspapers, the Monitor.

Martinez, the Pentecostal pastor, has another explanation. "There is no Mexican-American I know of who would refuse to go to war," she says. Which doesn't mean they support the war. In a recent survey of Latino voters by the Washington Post, Univision and the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute, nearly two-thirds of Latinos -- a significantly higher percentage than Americans in general -- stated they disapproved of the war in Iraq. However, unlike some Texans with friends in high places, Mexican-Americans still feel compelled to serve. Even so, Martinez says, pointing out that Garces was one of three members of her church to go to Iraq, "I sure don't want to have another casualty. But you know what? When I ask them if they would go back over there, they say, 'Yes, I would.'"

Tomas Garces, though, had his doubts. "At first, Tomas wanted to go to Iraq," his brother Ruben recalls. "But when he came home for vacation in August, he said he didn't want to go back. He was afraid something bad would happen."

Shares