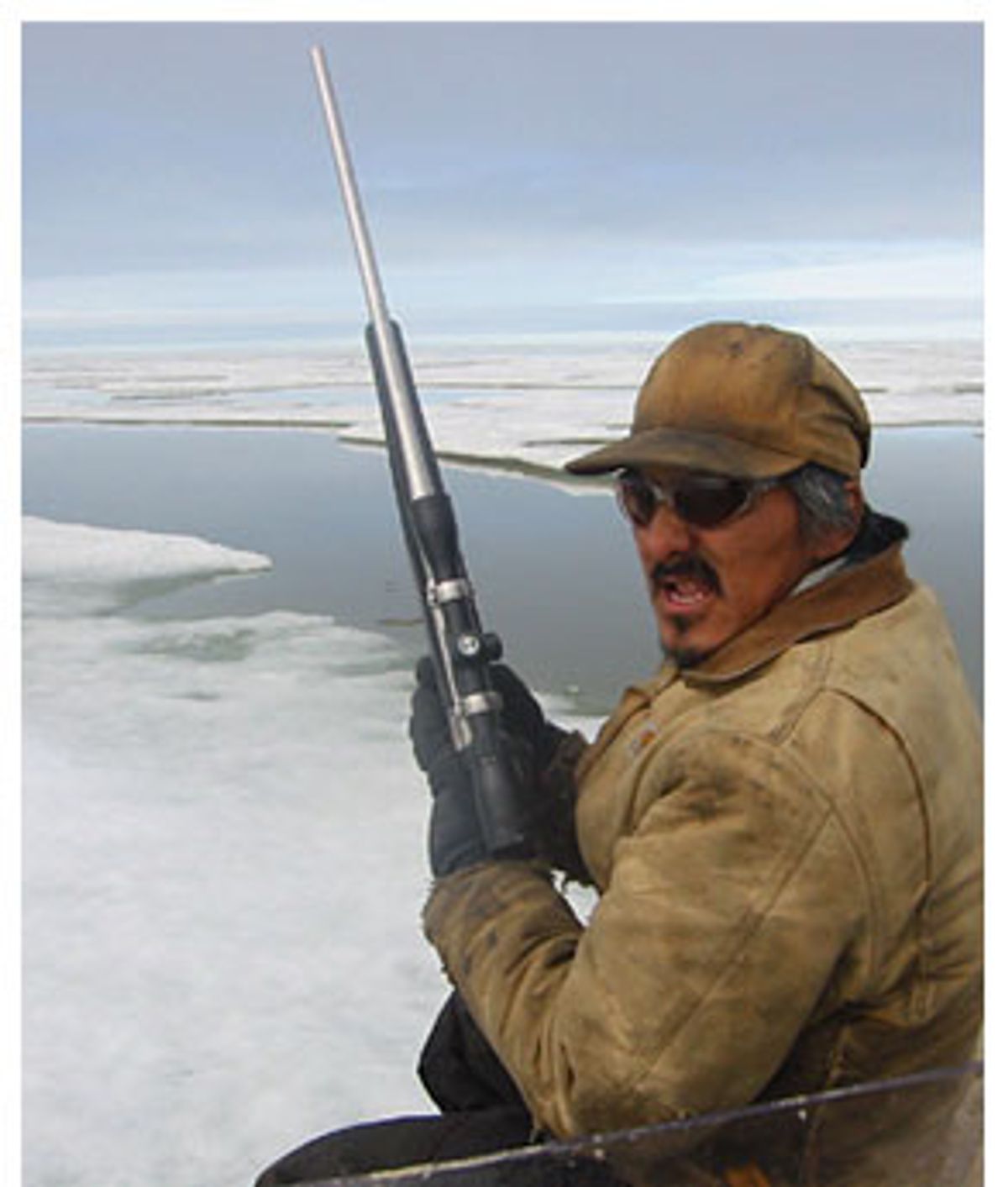

"Let's go shoot something," Jeffrey Long says with a grin, sliding his 18-foot boat into the water. We're 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle, in the Eskimo village of Nuiqsut, Alaska. I hop in next to Long and his friend Eli Kilapsuk, who are armed with a bolt-action Ruger M77, a couple of .22s, a 12-gauge shotgun, a harpoon and a vicious-looking hook for grappling with any kind of animal we might encounter today: caribou, geese, ring seal, bearded seal, walrus, even a polar bear. It's early July, more than halfway through the short Alaska summer when the sun doesn't vanish below the northern horizon, and Inupiat hunters like Long and Kilapsuk have only a few more weeks to harvest the season's bounty and lay in a store for the long winter ahead.

It seems like half the village is patrolling the rivers and channels this evening, their outboards buzzing like the ubiquitous mosquitoes. Kilapsuk, 29, his black ponytail flapping under his "Native Pride" brim, uses the VHF to trade reports with other hunters in both English and Inupiaq. I ask Long, 38, if we're likely to bag a caribou, or tuttu, as they're known in Inupiaq. The Inupiat use virtually every part of the animal in their daily lives: the meat for steaks, stews, roasts and jerky; the skins for parkas and winter boots; the sinew to sew together traditional whaling boats; even the brain, which is rubbed into leather to soften it. Along with the bowhead whale, caribou represent a cornerstone of Inupiat life. Long, who looks like an Eskimo Bruce Springsteen, with salt-and-pepper hair and scraggly goatee, throws the throttle down on his 70-horsepower Yamaha. "What we get, we get," he says.

We speed down the Nigliq channel toward the ocean seven miles away, eyes peeled for motion on the tundra above the banks. "Look, somebody got a caribou," Long says, pointing to a pair of eagles feasting on a gut pile.

Suddenly, out of the vastness that is Alaska's coastal plain, I see the incongruous silhouette of an airplane. I point it out to Kilapsuk, who has long since taken it in.

"DC-6," he says, without looking at it again. "Cargo plane. Going to Alpine."

His spare words contain more than a trace of bitterness. Alpine is an oil field, one of dozens of new and proposed developments popping up around Nuiqsut like poisonous mushrooms, transforming the open tundra into a vast complex of brown gravel pads, white elevated pipelines, lime green processing facilities, bright orange storage tanks and white Quonset huts. The oil rigs lie on the edge of a vast area of the Arctic called the NPR-A, short for the Northeast National Petroleum Reserve, Alaska. Covering 23.5 million acres, it's the single largest unit of public land in America. It also contains crucial nesting areas for migrating birds and critical calving areas for hundreds of thousands of caribou. For the past 80 years, "biological hot spots" in the NPR-A have been off limits to oil drilling and other development, granted special protection by the federal government. But now the Bush administration, with its no-holds-barred push for oil production, is fast-tracking new oil fields throughout Alaska's North Slope, the cumulative environmental consequences be damned. If the administration has its way, its allies in the oil industry could soon displace the caribou and other wildlife around Nuiqsut -- and with it, alter a way of life that has survived among the Eskimos for more than 8,000 years.

As we approach Alpine, Long steers the boat past pump stations and drilling rigs that would look more at home in industrial New Jersey than they do here at the continent's northern edge. A helicopter rotors by and a flock of geese scatter. I ask Long what he thinks about Bush's effort to expand oil drilling across the North Slope. He shrugs. "We tried to stop Alpine, but we couldn't," he says, as we motor past one of the drilling sites. "It bothers me, but what are you going to do about it?" Kilapsuk, as usual, is even blunter. "Man," he says, shaking his head, "it's messed up."

Long, sensing that the caribou have wandered too far inland for us to hunt, turns the boat out to sea to hunt seal. About five miles offshore we reach the edge of the broken ice, blue-green and white chunks floating in a sea of gray-green water. We park on a mini-iceberg and sip coffee as if we were holed up in a cafe rather than floating in the Arctic Ocean. Soon we see a ring seal bobbing its head above the water, and scramble to follow it in the boat. Kilapsuk takes a shot, misses. The seal dives underwater, but the sea is so calm that we can follow its underwater trail. When it surfaces, Kilapsuk hits it with the 12-gauge. Long hops on the bow, harpoons the dying seal and hooks it on board, the first of three natchiq we will harvest today. "The elders love this," Kilapsuk says. Since it is the first seal of the year, he explains, he'll give it away in traditional fashion to people in the village who don't have men to hunt for them. "Have you ever had caribou meat dipped in seal oil?" he asks. "It's good munchies."

Alpine development near Nuiqsut.

The NPR-A may not be as well-known as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge -- the unspoiled tract of federal land in Alaska that Bush has made the unsuccessful centerpiece of his energy plan -- but it's every bit as vital to the environment as ANWR. The remote area around Teshekpuk Lake, a sprawling maze of undulating marshes, grassy meadows and rolling green tussocks of moss, is considered one of the most important tundra-wetland ecosystems left on the planet. In addition to the caribou herds that give birth around the isolated lake each spring, rare birds flock here from as far south as Antarctica to breed, nest and molt: Arctic terns, the threatened Steller's and spectacled eiders, northern pintails, tundra swans, Pacific black brants and rare yellow-tailed loons. The area is "the most important goose molting area in the circumpolar Arctic," says John Shoen, a former Alaska state wildlife biologist and current senior scientist for the Audubon Society. Schoen says that the cumulative effects of all the proposed development -- from roads to seismic exploration -- would unequivocally cripple critical wildlife habitat. "All of the science is clear," he says.

Since the NPR-A was set aside as a strategic reserve in 1923, oil companies have been barred from drilling around Teshekpuk Lake. In 1998, when the Clinton administration opened a big chunk of the reserve to drilling, it made sure to place nearly 600,000 acres surrounding the lake off-limits to oil and gas leasing. But over the past year, while environmentalists have been focused on the fight to protect ANWR from drilling, the Bush administration has quietly moved to strip Teshekpuk Lake and other key "buffer zones" of their protections and auction them off to big oil companies. "ANWR was a convenient distraction," says a state wildlife biologist who declines to use his name because of political sensitivities. "It kept people from noticing that Bush's steamroller of development is already moving west across the North Slope."

In June, Interior Secretary Gale Norton put 8.8 million acres of the NPR-A's "Northwest Planning Area" up for bid -- a move that netted $53.9 million in oil leases. Companies like the European giant TotalFinaElf and the Canadian company Petro-Canada, as well as ConocoPhillips Alaska and Andarko (which are already vastly expanding the Alpine Satellite fields near Nuiqsut), hope to cash in on the new Arctic bonanza. Absent any objection from whoever's in the White House, the westward push is expected to continue, with new fields consecutively coming on line over the next decade.

After the Northwest lease, the Bush administration quickly took steps to open more area to leasing, notably including the critical area around Teshekpuk Lake -- and has developed a novel way to speed up the process. Instead of evaluating how oil companies could harm the environment, the administration has ordered federal land managers nationwide to do exactly the opposite: consider how the environment could harm oil companies. Land managers must now file a "Statement of Adverse Energy Impact" justifying any provision that protects the NPR-A from development, and grant "exceptions" to environmental safeguards that the industry considers "economically prohibitive." In addition, the administration-backed National Energy Bill wending its way through Congress also gives the interior secretary extraordinary discretion to allow oil companies to drill in the NPR-A without paying royalties if doing so "is in the public interest."

"This administration considers any level of protection to be too much," says Brooks Yeager, a senior Interior Department official in the Clinton administration who was intimately involved in opening up new leasing in the NPR-A in 1998. Yeager, who now works for the World Wildlife Fund, says that the science supported some drilling in the reserve, but also supported keeping some areas off the table. The Bush administration, says Yeager, "obviously regarded any restrictions as unnecessary."

In the past, the Inupiat have often sided with industry in fights over development. Eskimos, by and large, have viewed environmentalists with distrust since the Save the Whales campaigns of the 1970s helped deprive the Inupiat of a critical subsistence resource for years. "We don't want to hold hands with environmentalists," says Leonard Lampe, a former Nuiqsut mayor and president of the native village of Nuiqsut. "They were against our bowhead whale harvest." These days, people like Lampe are ready to bury the harpoon and work together with state and national environmental groups to slow down oil development.

As long as federal officials agree to protect wildlife needed for subsistence hunting and keep royalty payments flowing into local governments, Eskimo leaders on the North Slope have generally supported oil drilling in places like Nuiqsut. But that good will diminished quickly during the current administration. First, oil giant ConocoPhillips proposed expanding its small, contained oil pad at Alpine into a multisite industrial complex that will crisscross the area with oil pipelines, bridges and miles of new roads. Then the Bush administration proposed new offshore oil rigs in the Beaufort Sea and rushed to tear up the Clinton-era protections for Teshekpuk Lake that had been approved only a few years earlier.

"I really feel like we've been stabbed in the back," says Taqulik Hepa, deputy director of wildlife management for the North Slope Borough, a political conglomeration of eight Eskimo villages. "The more they want, the more people they impact."

The sale of oil leases in June shook up people in Barrow, where Hepa lives. It was the first significant development approved around America's northernmost city, which serves as the seat of Eskimo government. And the plan to allow drilling in millions of acres around Teshekpuk Lake has enraged even more people -- including the area's most powerful politician. "It seems that all sense of balance has been lost," says George Ahmaogak Sr., now in his fifth term as mayor of North Slope Borough. "The politics of power and influence are clearly at work."

The village of Nuiqsut -- Inupiaq for "a beautiful place over the horizon" -- may be one of the most isolated towns in America. No public roads link it to the outside world; I arrived on an ancient Cessna that runs supplies to the village store. The town, abandoned in the 1940s, was resurrected in 1973 after Congress required the Inupiat to create village corporations in order to claim land rights. Nuiqsut families lived in tents for the first year, eventually building a grid of raised gravel roads and small plywood houses perched on pylons that they pounded into the permafrost. The town displays hallmarks of the rural poor; cars are not so much abandoned as forsaken, windshield-less and wheel-less, amid a landscape of oil drums, snow machines and children's toys. But look closer and you'll see signs of Inupiat self-reliance, a way of life that has endured for thousands of years. Bull moose racks of impressive size adorn the doorways of several homes; fox and caribou skins cure in front of others; a collection of musk oxen skulls peer out from one rooftop.

People in Nuiqsut live not so much off the land as with the land. Since agriculture is virtually impossible in a place with a two-month growing season, villagers depend on subsistence hunting for much of their food. Once the ice melts and the waterways open up in early summer, the Inupiat hunt seal and caribou. By August, there will be moose, ripening salmonberries and more caribou. There are whales in autumn, wolf and wolverine in winter, geese in the spring. At different times throughout the year there are whitefish, Arctic cisco, char, grayling and other fish. Each Nuiqsut resident eats 750 pounds of subsistence-gathered meat and fish per year, a high-fat diet essential to survival in the harsh Arctic environment. The Inupiat desire to protect wildlife like caribou from oil drilling has nothing to do with a knee-jerk, save-the-seals reaction. They just want to make sure there are enough tuttu to shoot. The continued dependence on hunting and gathering makes even more sense after a trip to the AC Store, the only one in town. A dozen eggs cost $3.69, a loaf of Wonder Bread is $5.39, a half gallon of milk runs $7.59, and a half gallon of Tropicana orange juice goes for $9.99. Villagers frequently talk about the exorbitant price of what they call "store-bought food." With relatively few full-time jobs in Nuiqsut, hunting remains a necessity for everyone. "Even for me, I need the subsistence resource," says Isaac Nukapigak, president of the Kuukpik Village Corp., one of the best-paid jobs in town.

These days hunters around Nuiqsut use modern tools such as high-powered scopes and global positioning systems, but that doesn't mean the old ways are forsaken. "My son likes Froot Loops," says Rosemary Ahtuanguruak, the mayor of Nuiqsut. "But he prefers quaq" -- the Inupiaq word for a frozen snack of raw meat or fish. Ahtuanguruak has just finished emceeing a fish-scaling contest at the annual Fourth of July games, where the village's reliance on subsistence hunting is evident in the day's scheduled events. Adults line up at the local community center to see who can gut whitefish the fastest, and toddlers at a baby Eskimo fashion show model parkas lined with red fox and traditional boots made from caribou and bearded seal skin.

Ahtuanguruak first started getting alarmed about oil development in her former role as a health aide at the village clinic. After the oil pad went in at Alpine, she began noticing high rates of asthma among local residents, especially when gas flares were noticeable. Rates of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and thyroid disorders rose -- and so did truancy, vandalism, drug abuse and other social problems associated with oil development. Fish became sick or infected with parasites from pollution. Hunters talked about being driven away from traditional hunting areas by security patrols for the oil companies, and caribou began passing farther and farther from the town. Up here, seeing the caribou change their migration routes to avoid drilling rigs isn't just inconvenient -- it's as alarming as if every grocery store in your town suddenly moved 30 miles away, and the only way to shop entailed a long and arduous trip in sub-zero weather. "The land is our store and our garden," Ahtuanguruak says. "We know that development is going to occur. We just ask that it happens without taking food off our tables."

At one point during my all-night hunting trip with Jeffrey Long and Eli Kilapsuk, the two men pull their boat up to a ramshackle cluster of cabins along the water. Lydia Sovalik, a village elder, stands at a wooden table, elbow-deep in a caribou carcass, hewing hunks of meat with her ulu, a curved Eskimo knife. Sovalik asks Long and Kilapsuk to pull in her fish net from the channel. They return with a white plastic bag full of writhing whitefish, which Sovalik will dry and cure with driftwood to make what people say is the best smoked fish in Nuiqsut. She worries aloud that the current oil push is causing too many problems, multiplying construction zones and driving away the caribou. "Now we got troubles," she says, sounding like an Eskimo version of a Southern blues singer. "Things are changing so fast."

Back at the village, I ask around and learn that Gordon Brown and his 16-year-old son Curtis Ahvakarna had bagged the caribou I saw feeding the eagles out near Alpine. Two caribou, in fact. With the twin heads perched on top of their boat, Curtis recounted how he had circled a herd of 500 caribou while his dad took down two big bucks. They field-dressed the animals, loaded them in the boat, and proceeded to share the meat with family and neighbors. "My favorite is caribou," Curtis confides. "I don't really like moose."

Brown, a newly elected member of the native corporation's board of directors and a mechanic for the North Slope Borough, doesn't think that outsiders understand that subsistence hunting isn't some quaint, archaic hobby -- it's what holds the Inupiat culture together. "It's still a way of life here," he says. "That's what's being jeopardized by the oil companies coming through." Like many other Nuiqsut residents, Brown openly expresses his anger at the oil firms and the Bush administration -- outbursts unusual in a culture that values comity more than conflict. "It's irreversible if it all goes wrong," he says. "When you say 'irreversible,' it scares you."

From Brown's house, I walk across town to visit Margaret Pardue, a village council member who has just returned from testifying at a public hearing on the NPR-A in Washington, D.C. A soft-spoken woman raised in a traditional household, Pardue is still riled up from the trip. She complains that the administration scheduled the hearing over the Fourth of July weekend "so nobody would attend" and scoffs at the suggestion that her testimony might influence federal officials. "It goes in one ear and out the other," she says. All the administration wants, she contends, is to "get the oil as quick as they can and who cares what they leave behind."

The White House insists that more domestic energy production is essential to improving national security. A month after 9/11, President Bush told reporters that "a critical part of homeland security is energy independence" and urged Congress to pass his energy bill that included more Alaska drilling. Vice President Dick Cheney's controversial national energy policy task force recommended more oil and gas leasing in the NPR-A as one of its top priorities.

But the irony is, more drilling in the Arctic would have no effect on gas prices at the pump and would never equal more than 2 percent of America's oil supply -- not nearly enough to pry the nation from its dependence on foreign oil. Even top energy executives admit that there's not enough oil in Alaska to make a difference. "We periodically hear calls for U.S. energy independence as if this were a real option," ExxonMobil chairman Lee Raymond said in a speech in June. "We do not have the resource base to be energy independent."

The Bush administration does have a few supporters among the Eskimos. Its most powerful ally is the Arctic Slope Regional Corp., an $1-billion-a-year organization that funnels oil money to the Inupiat community in the form of services and cash dividends. Richard Glenn, vice president of lands for the ASRC, says the corporation supports "responsible development" in the NPR-A because oil drilling is the only way to pay for schools, healthcare and other essential services. "We've been walking this tightrope between stewardship and development," he says. "That's the story of our lives." Glenn understands the local opposition to drilling in crucial areas like Teshekpuk Lake, but dismisses it as short-sighted. "Asking someone in Nuiqsut today how they feel about the oil industry," he says, "is like asking a patient in the middle of a root canal how he feels about dentistry."

In Nuiqsut, however, residents see the Bush administration's push to expand oil drilling in the NPR-A as far worse than a temporary toothache. "We're just going to be another lost people in this world," says Leonard Lampe, the former mayor. "If it were up to us, we'd have no development, period, in the Teshekpuk Lake area. We were assured that there would be no development up there. Now they come back and say, 'Sorry, we found some oil.' That makes us very mad."

Lampe, whom I had seen in another boat hunting seal while I was out with Long and Kilapsuk, grew up subsistence hunting and works hard to pass on the traditions to his children. He says that his 7-year-old already knows how to pluck a goose, and his 11-year-old will "throw temper tantrums" if he doesn't get caribou stew at least once a week. Lampe doesn't over-romanticize the modern subsistence life, but emphasizes how central it remains to everybody in the village. "We're a struggling people," Lampe says. "Like any culture, we're trying to keep a self-identity and move forward. We're desperate to hold on to our lifestyle and culture. We're just little boys compared to Bush and everybody else. But they should care about us because we're just like an endangered species. Once we're gone, there's no bringing us back."

Shares