"The cigarette dangles between the lips," wrote Susan Sontag in her 1963 essay on Albert Camus in The New York Review of Books, "whether he wears a trench-coat, a sweater and open shirt, or a business suit. It is in many ways an almost ideal face: boyish, good-looking but not too good-looking, lean, rough, the expression both intense and modest. One wants to know this man."

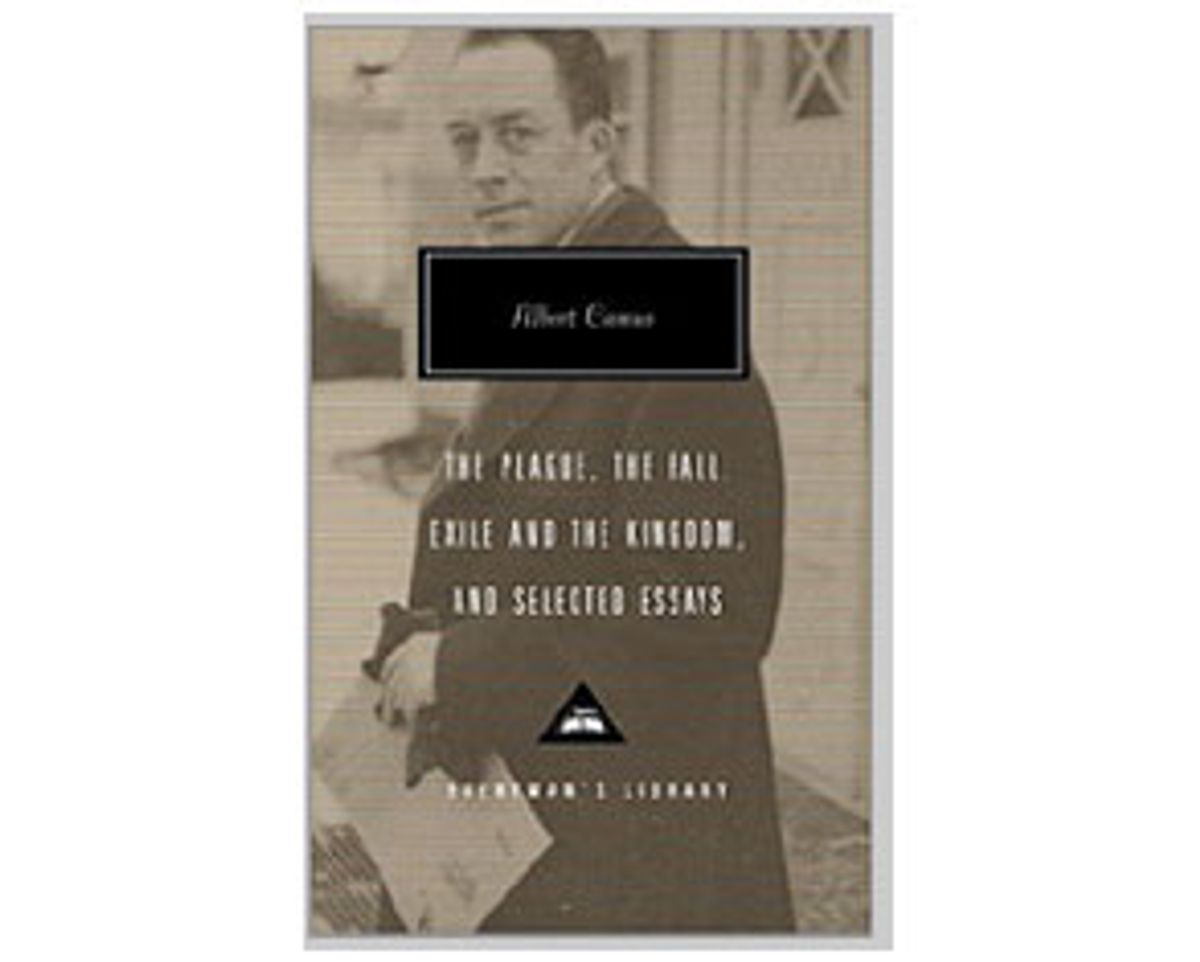

In the 44 years since Camus was killed in an automobile accident, readers all over the world have gone right on wanting to know him. Nearly all of Camus' major works are still in print. His best known novel, "L'Etranger," a title translated into English as both "The Stranger" and "The Outsider," is available in several translations and has scarcely been out of print since Knopf published it in English in 1946; "The Rebel," his cautionary essay on modern revolution, and his dramatic oeuvre, "Caligula and Three Other Plays," are both available in Vintage editions. The best biography of him, Olivier Todd's "Albert Camus: A Life," published in English in 1997, is currently in reprint from Carroll and Graf. Everyman's Library has just released three of Camus's fictional works -- "The Plague," "The Fall," and his only collection of stories, "Exile and The Kingdom" -- along with his most famous essay, "The Myth of Sisyphus," and his argument against capital punishment, "Reflections on The Guillotine," in one volume. And last year, the University of Nebraska Press made a valuable contribution to Camus studies with "Correspondence, 1932-1960," a collection of letters written between Camus and Jean Grenier, the author's philosophy teacher and mentor.

The availability of his work and the constant flow of new books and articles about him almost make Camus seem more contemporary than writers who were born after he died. Every time there is a seismic shift in world politics, a swarm of new readers discovers him; no sooner had the dust settled from the collapse of the World Trade Center towers than commentators groping for a moral barometer were quoting Camus. Before long, both left and right were trying to pull him into their camp. Last year in The Guardian, Marina Warner flagged Camus' novel "The Plague" -- a metaphorical tale of a North African city wakened to consciousness when isolated by a deadly pestilence -- as a beacon for liberals. In Warner's view, "The Plague" is a "study in terrorism" which was "also a fable of redemption." In his book "Camus and Sartre: The Story of a Friendship and the Quarrel that Ended It," released last January, Ronald Aronson argues for Camus as a neo-con avatar.

He has already been a pop icon for several decades. In the first photographs Americans saw of him after World War II, he was wearing a trench coat and was both amused and pleased to find that Americans thought he looked like Humphrey Bogart. (One of his favorite movies was "The Big Sleep.") In the '50s, the author of "The Rebel" looked a little like an older James Dean, the star of "Rebel Without a Cause" -- an image reinforced by his death in a car crash. In the late '60s, posters with one of his most quoted lines, "In the midst of winter, I finally learned that there was in me an invincible summer," shared walls in college dorms with Jim Morrison and Mick Jagger. In the '80s, the Cure caused a minor ruckus with the record "Killing An Arab," inspired by an incident in "L'Etranger."

And -- talk about the absurd -- a few weeks ago, while watching an episode of the Madeline cartoon series with my daughter, I was startled to see a nun taking French school children on a literary tour of Paris and stopping at a café frequented by "Monsieur Albert Camus, author of 'L'Etranger.'" A cartoon version of the novel's protagonist, Meursault, is shown behind bars, wondering, "Who am I? What am I? Why am I here?"

Oddly enough, the more popular Camus the writer has become, the hazier the picture of the man has grown. As Todd writes, "Camus's own books do little to bring his personality into focus." His personal papers didn't help. "I've used the 'Carnets' [notebooks]," Todd says in his preface, "but sometimes I feel that Camus wrote them with posterity looking over his shoulder, not the way Gide wrote his succulent 'Journals,' but rather with the discretion of Johnson explaining himself to Boswell."

For many years, it was assumed that Camus' fiction -- particularly his last completed novel, "The Fall," about a judge who judges himself unfit to judge -- was highly autobiographical. It now seems that Camus was merely doing some selective borrowing from his own experiences. "The idea," he wrote in one of the last carnets, "that every writer ... portrays himself in his books is one of the puerilities that Romanticism has bequeathed us. A man's works often describe his longings or temptations, and almost never his own true story."

It's doubtful that Camus wanted his own true story told by anyone else, or that he thought there was a story to tell beyond his novels and essays. He may have been right; he inspired a plethora of biographies and studies, many of them useful but almost none of them satisfying. Herbert Lottman's 1979 biography of him gave us the facts of his life but couldn't capture the spirit of his work. French critics Albert Maquet and Germaine Brée and the Englishman Philip Thody wrote useful studies of his work presented against the sketchy backdrops of history. Irishmen Patrick McCarthy and Conor Cruise O'Brien wrote self-serving books criticizing Camus for not seeing the complex political issues of his time as clearly as they did. Todd's is the first full-length treatment written with an empathy for the cultures, particularly the now-lost world of the impoverished French Algerians that produced Camus, and the book's lack of an ideological agenda is refreshing. Some of Todd's interpretations sound radical in short form, but most won't come as surprises to careful readers of Camus' work.

For instance, no one who has read "The Myth of Sisyphus" and Sartre's "Being and Nothingness" needs to be told that Camus was never really an existentialist, which won't prevent him from being lumped with that school whenever a journalist is stuck for an easy handle. ("I don't at all feel I am an 'existential'," he wrote in a 1943 letter to Grenier, thus giving credence to those who believe that his philosophical views differed from the existentialists at the outset of his writing career.) Unlike Sartre, Camus never felt alienated by nature and the world, and in his notebooks he listed outdoor life as one of the conditions essential to happiness.

His mistrust of systematic philosophies in general, and Sartre's in particular, was one of the causes of their much-publicized falling out. The immediate cause for the quarrel, exacerbated by personal animosities, was the publication of "The Rebel," which Sartre and other Communist-leaning French intellectuals criticized for its rejection of Marxism.

The promises of Marxism, Camus felt, were ultimately as false as those of Christianity. The latter promised its followers "a beyond," while the former offered "a later," which, Camus felt, amounted to the same thing and was thus equally false. As for the existentialists, he wrote in "The Myth of Sisyphus," "Negation is their God." Camus was a devout agnostic and not a man to exchange a spiritual heaven for a materialistic one.

Albert Camus was born in Mondovi, Algiers, on Nov. 7, 1913. He never knew his father, who was killed in World War I. His mother was of Spanish descent; André Maurois felt "there was a good bit of the Castilian in Camus," especially the Spanish traits of dignity, nobility and poverty, and defiance in the face of death. Camus' education was hampered by a combination of poverty and a family who, like many of their kind, was not so much anti- as non intellectual. No doubt with some justification, his mother felt that Albert should have to work for a living, like his older brother Lucien who at age 14 was already working as a messenger boy. Camus had the good fortune to be sent to school, where an experienced teacher, Louis Germain, took him under his wing and gave him free lessons. (Many years later, Camus repaid the kindly instructor by portraying him in his unfinished last novel, "The First Man," which neither author nor subject lived to see in print.)

From there, Jean Grenier, a teacher at the local lycée -- a secondary school maintained by the government to prepare students for a university -- took over Camus' education, going so far as to bring him books in the hospital when Camus, after coughing blood in class, was forced to drop out. According to a friend quoted in the introduction to "Correspondence, 1932-1960," Grenier "created Camus and the literature of Camus." That's probably true, but it's an oversimplification; Camus was a student but not a disciple of Grenier, who was a mystic and a classic humanist. Camus, as Jan F. Rigaud, who translated the volume of Camus-Grenier letters, phrases it in his introduction, "did not leave the earthly kingdom. Camus would always rely on man himself and his own free will to be saved."

"He wasn't a boy who was made for all that he tried to do," said Sartre with uncanny insight. "He should have been a little crook from Algeria, a very funny one, who might have managed to write a few books, but mostly remains a crook. Instead of which, you had the impression that civilization had been stuck on top of him and he did what he could with it." That Camus didn't wind up a professional Algerian street rat might have had something to do with his contracting tuberculosis while in his teens. He never completely rid himself of the disease, which probably would have killed him before age 50 if he had not died in the automobile accident. Like other famous consumptives, from the gunfighter Doc Holliday to the country singer Jimmie Rodgers to fellow author Robert Louis Stevenson, he adopted a fatalistic attitude toward life tinged with sardonic humor. He was already intellectually precocious; the disease helped make him emotionally mature.

Many other factors conspired to shape Camus' outlook on life and existence: his intense love for his quiet, unlettered mother; his classic French education; his instinctive love for the Greek philosophers and poets (rather than the German philosophers who exerted such an influence on his French contemporaries) with whom he felt a Mediterranean kinship. None of these would prove so strong an influence as the sun and sea of his native Algeria, from which Camus derived the vision of the invincible summer he carried with him all his life. Far from Catholic France, surrounded by Muslims, the sea, and the desert, Camus grew up a 20th century pagan imbued with Christian-like piety. "It's true that I don't believe in God," he once said, "but that doesn't mean I'm an atheist, and I would argue with Benjamin Constant, who thought a lack of religion was vulgar and even hackneyed."

Or, as he told reporters in Stockholm at the Nobel Prize ceremony, "I have Christian concerns, but my nature is pagan." Surely a better combination than the other way around.

Despite his popular image as a professional pessimist, Camus was in fact possessed of an almost unnatural optimism. Sartre once derisively referred to it as "Metaphysical Quixotism," though Camus' optimism in the face of what he perceived to be the world's indifference probably accounts in large part to his continuing popularity. Camus always speaks to individuals, never to groups; despite the best efforts of those attempting to pigeonhole his philosophical and political beliefs, Camus, like George Orwell, remains relevant without being fashionable. In the words of Olivier Todd, he "used his novels and journalism to attack the obvious fortress of totalitarianism, communism, as well as bastions of Fascism, like Franco's regime. He was more or less alone in his struggle ..."

As a result, Camus was "treated like a traitor by the Communists because given the political climate in France, he was correct too early." It wasn't just France where Camus was correct too early: It was in the '80s that Susan Sontag (who once accused Camus of being "not that emotionally tough, not tough in the way Sartre is") angered old leftists by calling communism "fascism, with a human face" -- a statement that pretty much sums up what Camus had been saying since the end of World War II.

It was Sontag, in 1963, who offered what many thought at the time was the definitive judgment on Camus the writer. Claiming to judge "by the highest standards of contemporary art," she wrote that "his work, solely as a literary accomplishment, is not major enough to bear the weight of admiration that readers want to give it." Camus' cardinal virtue, she felt, was moral beauty, but "unfortunately, moral beauty in art -- like physical beauty in a person -- is extremely perishable." Perhaps not so perishable, it turns out, as Sartre's moral toughness. Whatever "the standards of art" (and whose standards would those be, Sontag's?), many seem willing to judge Camus on his own terms, not as a philosopher or even a novelist, but as he put it, "an artist who creates myths." Nearly half a century after most of his major works were published, he remains the most influential Continental writer in the U.S.; in France, says Todd, "Camus leads the pack ... with Jean Paul Sartre lagging far behind."

It's intriguing to think how Camus the writer might have evolved had he survived the automobile wreck. Would he have become an increasingly irrelevant embarrassment, as, to a large extent, Sartre has, to a generation that no longer puts faith in Marxism? Would he, as "The First Man" suggests, have become more of a pure novelist and receded from the increasingly turbulent 1960s political scene? Would the moralist of "The Myth of Sisyphus" and "The Rebel" be transformed into a neo-Christian mystic, a C.S. Lewis for old radicals?

Whatever development his thoughts might have taken, it's doubtful he would have strayed far from the path he initially laid out in "The Myth of Sisyphus": "A man is always a prey to his truths. Once he has admitted them, he cannot free himself from them." Camus could not deny what he felt were his truths even when political expediency would have served him well. For instance, he refused to endorse the Algerian Revolution, which earned him more enmity, perhaps, from leftist intellectuals than his rejection of Marxism. Sontag's comment on his emotional toughness was a criticism of his agonizing inability to take a stand on the Algerian question: "Moral and political judgment," wrote Sontag, "do not always so happily coincide." Indeed they do not, as so many French, English and American intellectuals discovered when the Algerian nationalist group they endorsed proved to be as brutal and despotic as any fascist engine.

Which is why anyone who tries to reduce Camus' work to fuel for political punditry is ultimately doomed to failure. Moral and political judgment being so often incompatible, we need reminders that the moral judgment is the less perishable.

Shares