The current war inside the CIA began with a stolen package of bacon. During a 1981 grocery run in Langley, Va., Michael Kostiw decided against paying $2.13 for a few strips of salted, fatty pork. Unfortunately for him, his 10 years of experience as a case officer for the Central Intelligence Agency was poor training for petty thievery, and after he was caught by supermarket employees the CIA placed him on administrative leave. He opted for a quiet retirement from Langley.

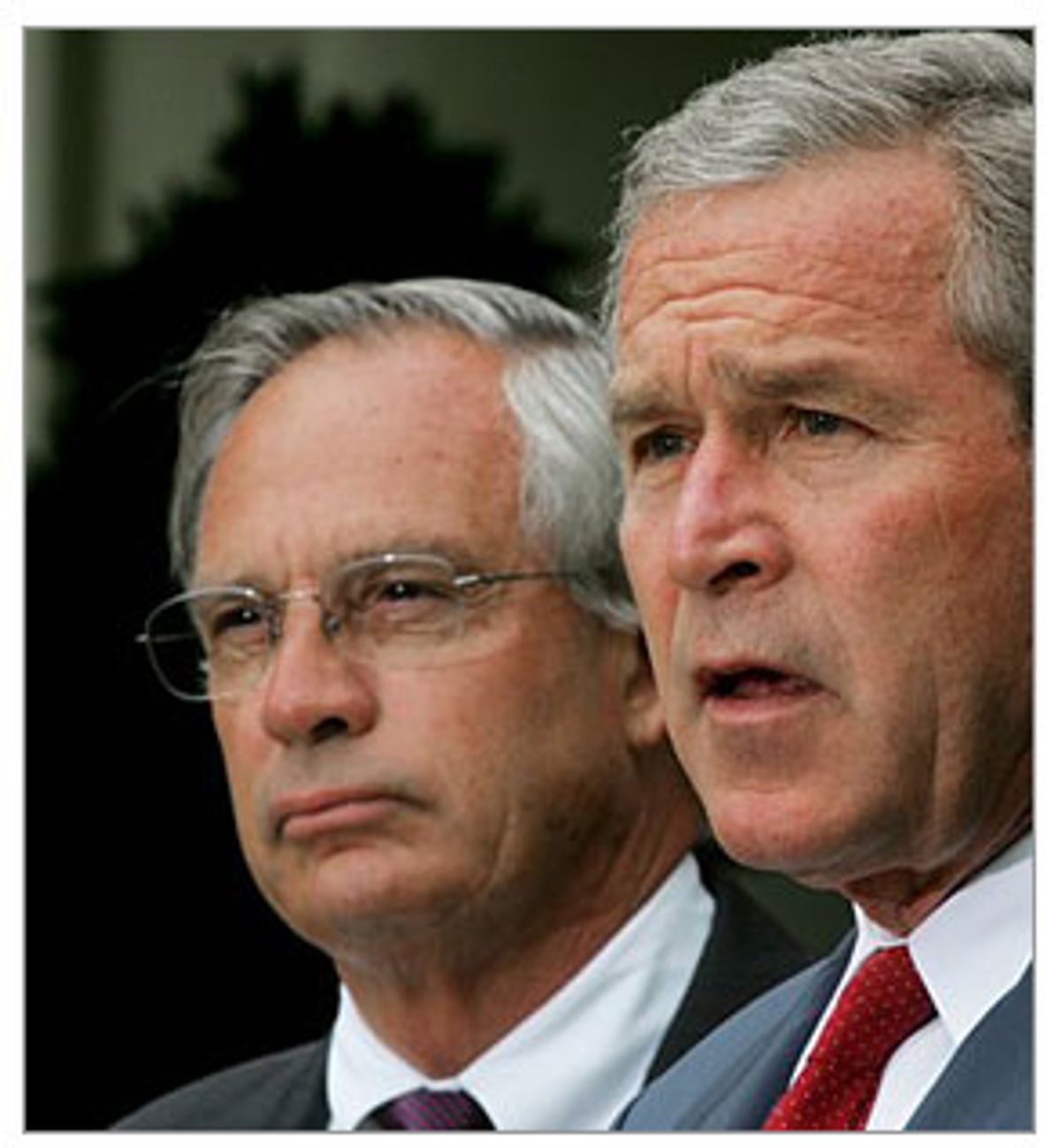

But not long ago he was back -- briefly. When Porter Goss, a Republican representative from Florida and chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, became director of central intelligence on Sept. 24, he named Kostiw, his chief staffer on terrorism, as his executive director, Langley's third in command. The prospect of Kostiw, a partisan GOP Hill staffer, effectively running day-to-day affairs at the CIA was too much for some of his prospective employees to take, however. Although the agency had prevailed on the local authorities over 20 years ago to wipe Kostiw's police record clean, Walter Pincus, the veteran intelligence reporter for the Washington Post, related the long-forgotten bacon heist on Oct. 3, citing "four sources." As one former intelligence official observes -- not without a hint of admiration -- "that was a vicious leak." And it worked. Within days, a humiliated Kostiw withdrew his name from consideration for the position. Chalk up a scalp for the CIA.

These days, however, most of the scalps belong to longtime intelligence officials. Since his appointment, Goss has given his top aides -- basically, his former staff from the intelligence committee -- the green light to draw up lists of people to fire. The zeal with which Goss' enforcers are exercising their power has led to angry resignations by top CIA veterans like Stephen Kappes, who had taken over as deputy director of operations just this summer, and brought the brutal shakeup onto the front pages. The CIA's case officers and analysts, meanwhile, are extremely distressed by Goss' slashes at the professional staff. "I do nothing but talk to disgruntled and sick people there," says a recently retired senior CIA official.

And that suits the White House just fine. Many conservatives in and outside the administration, especially the neoconservatives, view the CIA as a subversive element bent on stymieing Bush's agenda. The last several months of the presidential campaign saw a series of intelligence disclosures concerning Iraq and the war on terrorism that the White House regarded as intended to derail Bush's reelection. Many agency employees believe that administration officials rewarded them for their best efforts at divining the truth about al-Qaida, Iraq, nuclear proliferation and other urgent threats to U.S. national security with derision, political pressure and blame for the mistakes of policymakers. Now, with the arrival of Goss as DCI, they see the Bush administration intent not so much on reforming the CIA as crushing it. And as is already clear, many intelligence veterans don't plan on going quietly into the night.

There's a good chance that 2005 will be the worst year ever in the history of the CIA. That's saying a lot, considering black marks -- real and perceived -- like the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco, the 1975 and 1976 "Church Committee" (led by Sen. Frank Church) reports that compared the agency to a rogue elephant, and the successful al-Qaida attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. But consider what the CIA faces in the coming months. In March, the so-called WMD Commission is scheduled to deliver its report rating the intelligence community's performance on combating the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Since Bush established the commission in February as a means of deflecting the political controversy that arose from the absence of WMD in Iraq -- in essence, premising the commission on the question of what other proliferation threats the CIA might have screwed up -- its report is expected to be scathing in its criticism of intelligence professionals.

And that's just for starters. The biggest shock the CIA is bracing itself for is the reorganization of the intelligence community recommended by the 9/11 commission. While the exact contours of the restructuring are still subject to arduous conference-committee reconciliation between House and Senate negotiators, the CIA stands to lose its cherished position as first among equals in the intelligence community. "People are absolutely freaking out," says a retired CIA official. "Their whole structure is being rehabbed and they don't know how. The uncertainty makes them crazy."

Into this den of anxiety stepped Goss, hardly a reassuring figure. Though Goss is a former CIA case officer himself ("a hundred years ago," sniffs a former official), it didn't exactly endear him to the agency when he shed his reputation for relative bipartisanship and professionalism to write opinion articles accusing John Kerry and other Senate Democrats of slashing intelligence funding while he chaired the House Intelligence Committee. (Never mind that Goss himself cosponsored a 1995 deficit-reduction measure that entailed firing 20 percent of CIA personnel over five years.) And while promoting the president's political ambitions, he was hardly subtle about his own. After stifling a proposal by Democrats on the committee to consolidate the fractious intelligence community earlier this year, Goss reversed course in June to propose giving the DCI control of 70 percent of the estimated $40 billion intelligence budget (nearly 90 percent of which is controlled by the Pentagon) -- precisely at the same time he was dropping hints around Washington that he wanted the job.

Even more vexing to CIA veterans was Goss' willingness as a congressman to demean the agency if it meant protecting Bush. Though Langley had successfully prevailed on the Justice Department to investigate an administration leak of the identity of undercover operative Valerie Plame -- a potentially criminal act aimed at discrediting Plame's husband, Ambassador Joe Wilson, who had exposed Bush's duplicity about supposed Iraqi attempts at acquiring nuclear material from Niger -- Goss dismissed the entire scandal as "wild and unsubstantiated allegations." He tastefully told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune in October 2003, "Somebody sends me a blue dress and some DNA, I'll have an investigation."

But Goss tossed his most deadly grenade into Langley in June by attaching a report to the annual intelligence authorization bill calling the agency "dysfunctional" and accusing it of "misallocation and redirection of resources, poor prioritization of objectives, micromanagement of field operations and a continued political aversion to operational risk." This attack appeared while Goss was actively campaigning to replace George Tenet, who had suddenly announced his retirement as DCI that month. Some CIA officials saw Goss' grandstanding as a way of endearing himself to Bush. As a parting shot, Tenet even posted on the CIA Web site a letter to Goss passionately calling his report "frankly absurd" and "ill-informed." But Tenet's letter failed to stop Goss' nomination and confirmation as DCI.

Goss brought with him many of his principal congressional aides, who bear a reputation for condescension and hostility to the CIA, as well as fierce partisanship. "Kostiw's the best of the bunch," says a retired senior official. "Words fail me to describe the rest of them." And Goss didn't just give them top positions in the agency, he invented new posts for them, as mediators between the DCI and the intelligence and operations directorates. "They are not positions that are rigorously defined in agency regulations," observes Steven Aftergood, an intelligence policy expert with the Federation of American Scientists. "Rather, they are invested with whatever authority Goss wants to give them, which means they could be very important indeed."

As his chief of staff and senior advisor for strategic programs, Goss brought two senior Republican House Intelligence Committee aides, Patrick Murray and Merrell Moorhead. Clashes with Murray led to Kappes' departure on Monday. But some CIA officials are particularly concerned about Jay Jakub, a former GOP subcommittee staff director who's now Goss' nebulously titled senior advisor for operations and analysis. Jakub, a principal author of the June intelligence committee report, was a CIA analyst and case officer before serving as chief investigator on ultraconservative Rep. Dan Burton's inquiry into Democratic campaign finance during the 1996 election. "He's widely viewed as having very strong partisan views," says one of Jakub's former CIA colleagues. "Jay leaps too early. He acts on his views, and often doesn't seem like a measured decision maker." (Through a spokeswoman, Goss and his senior staff declined requests for interviews.)

Many at the CIA fear that Goss will enforce loyalty to the Bush administration at the expense of good intelligence work. "A word I heard a lot from Goss is 'teamwork,'" says a just-departed agency official. "Whether he meant teamwork inside the building or with the administration, I don't know. But I suspect he means the latter." Adds another retired official, "One thing everybody is watching with some concern is how far down the politicization goes. It's been very contained up to this point. It's not just how intelligence gets treated and slanted, but how these people bring partisanship into a lower level" of Langley officials. And if that happens, says the first official, "we lose the reason for our existence. If there's any hint of pressure, it's worse than having no intelligence at all."

Illustrating this fear is the cautionary tale of the CIA's 2002 examination of the dubious connection between al-Qaida and Saddam Hussein. As a result of intense pressure from senior Bush administration officials, including Vice President Cheney -- many of whom had already concluded that a solid connection existed -- CIA analysts prepared a report titled "Iraq and al-Qaida: Assessing a Murky Relationship." Or at least a few of them did. Circulated that June, as the administration sought rationales for an invasion of Iraq, the report excluded the assessments of the agency's Near East and South Asia (NESA) office, which generally cast doubt on either an existing or a prospective alliance between Saddam and Osama bin Laden. The paper was chiefly the product of the CIA's terrorism analysts, who explained that their approach was "purposefully aggressive in seeking to draw connections, on the assumption that any indication of a relationship between these two elements could carry great dangers." Jami Miscik, the CIA's deputy director for intelligence, told Senate Intelligence Committee investigators that the paper was intended to "stretch to the maximum the evidence you had." The exclusion of NESA prompted an inquiry by the agency's ombudsman into politicization.

Despite CIA professionals' general skepticism about the White House's desired conclusions and attempt to stay within the confines of responsible intelligence work, a slanted study still emerged. Yet the facts did constrain the analysis, and the report stated that there existed "no conclusive evidence of cooperation on specific terrorist operations." In frustration, a Defense Intelligence Agency analyst detailed to the office of Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith, who sponsored much of the effort to manipulate intelligence to connect al-Qaida to Saddam, contended to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and his chief deputies that the "CIA's interpretation ought to be ignored." (In its public pronouncements about the alleged ties, the Bush administration generally followed the DIA analyst's advice.)

Now, with Goss at the helm and the independence of the agency under siege, many at Langley fear that the Bush administration won't have to worry anymore about being told anything it doesn't already believe.

The widespread animosity toward Goss is likely to mark his entire tenure. Effective, long-lasting DCIs typically owe their success to an ability to balance three constituencies: the White House, Capitol Hill and Langley. DCIs who neglect their CIA power base don't often survive or implement much. Goss seems to be predicating his career on deliberately antagonizing the agency and forcing it into submission. But without the support of the agency he runs, Goss will be forced to rely on the warm wishes of the president for his continued service, which will only escalate the bitterness between Goss and the CIA.

The director has already shunned those who've pleaded for conciliation. Four former deputy directors of operations attempted to "tell him to stop what he was doing the way he was doing it," an ex-senior official told the Washington Post, but Goss refused to meet with them. As tensions rise between Goss and the agency, they risk becoming mutually reinforcing -- and difficult to defuse. If Goss thought the CIA was dysfunctional before, he has guaranteed that it is now. Caught in the balance is the intelligence work indispensable to waging the war on terror. "If the trust [in CIA leadership] isn't there, you just can't be successful," warns a former intelligence official who worries about operatives and analysts having to keep one eye on bin Laden while reserving the other for fighting off their bosses.

Backed by a White House that rarely fires its loyal subordinates, Goss could very well be at Langley for a long time despite his shaky start. When Goss gave his introductory address to CIA employees in September, he received two standing ovations -- when he walked in and again when he finished up. A former CIA official who was present at the ceremony remarks, "Let him do it again today. He'll probably need security."

Shares