John Brady Kiesling is a retired career diplomat who has served in embassies from Athens, Greece, to Tel Aviv, Israel. In February he resigned in protest of the Iraq war.

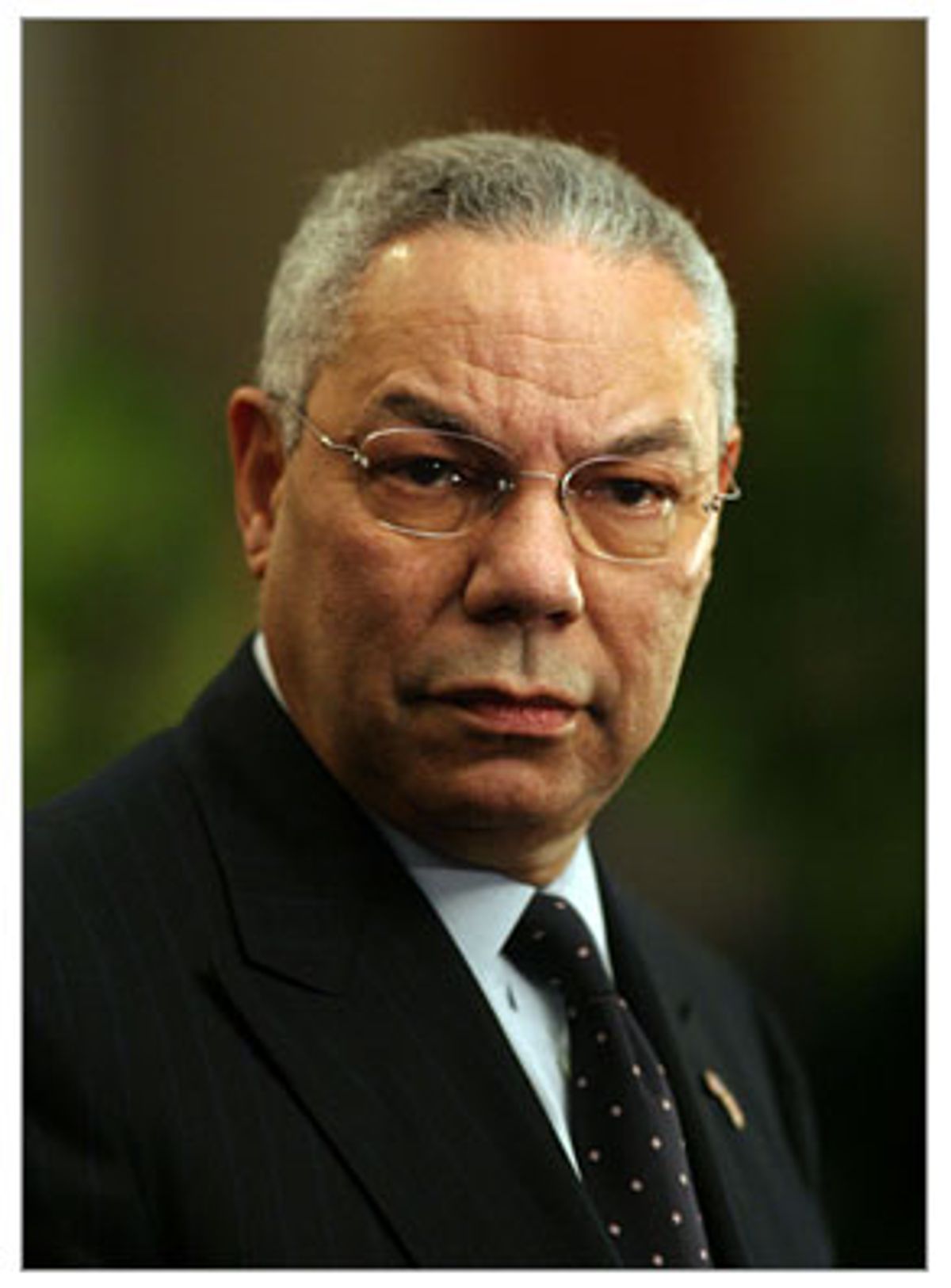

Colin Powell should have been a great secretary of state. He was free of Kissinger's brutalizing ideological blinders, was more realistic and less insecure than Madeleine Albright, and was, unlike the cynically efficient James Baker, a charismatic leader and loyal manager to his staff. When a free-spending administration opened the taps, Powell was a capable bureaucrat, assuring an undernourished State Department its 15 minutes at the federal trough. And Powell had a genuine flair for diplomacy, a human touch that reassured foreign counterparts that competing interests could somehow be reconciled.

But Powell hesitated, fatally, to use his independent political standing to defend rational policies against domestic extremists. He allowed 20 years of painfully evolving nonproliferation consensus to be blown to atoms by his U.N.-hating undersecretary, John Bolton. He allowed the State Department's regional experts to be driven out of the Iraq policy process by Vice President Cheney's circle of Chalabi-worshippers. He trusted the director of Central Intelligence when Tenet made his desperate leap of faith on Iraqi WMD to placate a war-hungry president.

The neoconservatives deride diplomats for their conviction that most conflicts are never truly resolved, only managed. Powell thought he could manage the contradiction between red state ultranationalism and traditional U.S. stewardship of a fragile international system. If Powell had resigned when his resignation mattered, President Bush might have learned a sharp, useful lesson about the political costs of ignoring his professionals. By waiting a full four years, Powell took himself out of the history books. He was not to blame for the poor decisions that squandered a generation's worth of America's accumulated moral and political capital. But neither can Powell take the credit should it be proved, as the world still hopes, that America learned something useful in the process.

Chris Preble is director of foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute.

The big question now is who will replace Powell, and I think it's going to be an indication of the direction of the Bush administration's foreign policy: whether they're going to go further in the neoconservative direction, or if they're going to hew more to the traditional Republican realism of Bush Sr.

But whoever replaces him will not have a comparable stature to Colin Powell. It is a genuine anomaly when the secretary of state enjoys wide, popular political support -- perhaps greater than the president himself. So whoever is the next secretary of state will be less able to shape policy independently of the president, and I think it's virtually inevitable that the president will exert much more control over foreign policy. That control will likely extend into the department itself -- not just in policy, but in the nuts and bolts implementation, and the analysis that goes into making policy.

I think Powell's supporters, many of whom happen to be Democrats, are going to be very active in trying to sustain his reputation, particularly if in the second Bush administration things go south and there's a desire to try to pin some of the problems on the dearly departed. The common refrain I've heard among his supporters who are not happy with Bush's foreign policy is, "Well, if it weren't for him, it would have been a lot worse."

That's a plausible argument, but at crucial times -- say in his February 2003 speech before the United Nations, or very early in the administration with respect to Korea or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict -- he has as often as not appeared publicly to give credibility to the Bush administration, not rein it in.

As a historian who studied in great length Foster Dulles and other secretaries of state who appeared to have an enormous amount of personal influence, I have to say I'm going to be looking at the contemporary history in a very skeptical light. You don't learn what they were doing until long after the fact, and I don't know that Powell's legacy will even be understood in his own lifetime. In the near term, however, he's going to be judged by the public face he put forward in support of policies that, though the jury is still out, looks like a mess, both in Iraq and elsewhere.

Charles William Maynes is the president of the Eurasia Foundation and the former editor of Foreign Policy.

When you look at the postwar history of the United States, there are only a few secretaries that have tried to tap the expertise of the department. [Dean] Acheson did it, and [George] Schultz did it. Many other secretaries have had a small cabal around them that made all the decisions and fended the bureaucracy off. Powell is in the tradition of trying to use the department, and for that reason, his popularity within the department is enormous. Had he prevailed in some of these debates, that popularity would have translated into huge influence in the administration.

But George W. Bush's administration decided for its own reasons to go ahead without some of our traditional allies, and without some of the organizations that in the past have conveyed legitimacy. Powell was an advocate of trying to work with those organizations. In the end, the administration has come around to some of his positons, such as seeking more U.N. and NATO involvement in Iraq. But for a long time he urged one position, and the administration chose another course. I think Powell is going to be seen as somebody who had a record of disappointment, but who was important to the administration in maintaining ties with other governments at a time when the American image in the world was challenged aggressively.

The image problem of the United States is no longer just a public relations issue, but a national security issue. One can see that in some of the polling done by the Pew Foundation in the Islamic world, where you get large majorities in support of suicide bombings against America, even in countries where the governments are historically friendly to the United States. Powell's presence as secretary of state helped make the damage to the image of America abroad less severe than it might otherwise have been. If the next administration is able to repair some of that damage, Powell will be seen as someone who salvaged an opportunity for the future. If the damage continues, I think he will be seen as a lonely figure that did not succeed.

Larry Birns is the director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

The last four years have had a disastrous impact on U.S.-Latin American relations, and I fault Powell for not taking enough interest in the region. He unleashed -- or did not protect -- the State Department from a gang of ideologues whom the Bush administration was very anxious to get into policymaking decisions, largely because of the Cuba angle.

Under Powell, American Cuban policy became more ugly, more unattached to reality, and more mano a mano, Bush vs. Castro. These were White House policies, and they were not as much about diplomacy as about domestic politics. If Powell ever had any influence to change them, he never moved to exercise it.

At times when elections were pending in Latin America, U.S. ambassadors to a number of countries were instructed to tell political leaders that the United States believes in free and fair elections, "but if someone is elected that we don't feel is good for our national interest, we will visit heavy consequences upon you." One type of democratic rhetoric was used in the political salons, and a different kind of bare-knuckle diplomacy used in practice.

But Powell's low point in Latin America was how he dealt with [former Haitian president] Aristide -- it was clear he had no policy. Within a week's time, he migrated from saying that the United States would not tolerate the overthrow of a constitutional government by "a gang of thugs" to a specious, disgraceful policy of saying that the United States would not send peacekeeping troops to Haiti until negotiations took place, negotiations that Aristide's opposition refused.

Powell made a very superficial assessment of the region, and did not see that there was real crisis among Latin American democracies. The administration's talk about the promulgation of democracy was pure puffery, and any number of Latin American presidents have been shoved out of office after being duly elected.

Robert V. Keeley was a U.S. Foreign Service officer for 34 years, including ambassadorships to Mauritius, Zimbabwe and Greece.

The news of Secretary of State Powell's resignation was certainly not a surprise, as it was rumored to be highly likely for some months. I cannot speak for my colleagues who are retired Foreign Service officers, although I am familiar with the views of a considerable number of former FSO's who participated as I did in a 527 organization called Diplomats and Military Commanders for Change that worked during the recent presidential campaign to promote "regime change" in Washington. Given the electoral outcome that did not bring in a new administration, most, perhaps all of them, will regret the departure of Secretary Powell.

Colin Powell brought many important skills, experience and a rational outlook to this very important Cabinet position. In some significant respects he was an outstanding secretary, who took an interest in the management of the Department of Foreign Service, obtained increased resources from the Congress for our diplomacy, and increased staffing levels that had been seriously depleted. He forced our diplomats to be better leaders and managers, and took a personal interest in all of the personnel of his department. For this outstanding performance two years ago he received the Excellence in Diplomacy award from the American Academy of Diplomacy, an association of retired senior diplomats. I believe my colleagues also regret his departure because although he was often not successful in modifying administration policies on important issues such as Iraq, terrorism and nonproliferation, he was a strong if mostly cautious advocate for diplomacy, moderation, rationality (or "realism") and pragmatism in national security policy. His departure removes this voice of reason from the higher councils of our government.

He disappointed some of us because he was often the loyal "good soldier" who went along with policies with which he disagreed. Dissent is not encouraged or respected in the military culture in which Powell lived for so many years; dissent is not often rewarded but is somewhat tolerated in our career diplomatic corps. The question that now faces us is who will replace him, and whether that person will advocate the same principles that Powell did, and will be more (or perhaps less) effective in countering the dominance of the neoconservatives over our national security policies.

Shares