I have this little theory that begins with Bob Dylan. As the quintessential singer-songwriter, he casts one long and cumbersome shadow. Inevitably, when a spirited young artist armed with a guitar or a microphone and a head full of wit, spit, aphorism and meter hits the scene, critics and music lovers muse over the question of whether the artist is a Next Dylan. They don't have to compare the newcomer directly to Dylan, or even mention Dylan by name. What they're asking, essentially, is: Have we found a new Voice of a Generation?

Only one character trumps the Next Dylan, and that's the Tragic Rock Star. These artists have transcended the Next Dylan plane by overdosing (Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious), getting shot and killed (John Lennon, Tupac Shakur, Notorious B.I.G. -- those last two in the subset or alternate category of Tragic Rap Stars) or, most pointedly, committing suicide. In death, they become symbolic martyrs. They are immortalized in their fight against an oppressively normal life. They had the courage (and talent) to live harder. We're drawn to their intoxicating excesses and romantic self-destruction, even if we reject it for our own sense of stability.

Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain was the most notable figure to ascend to Tragic Rock Star status in current times. As he amassed millions of followers, he tried to lose them in the distortion and fuzz he shot back at them. Despite this, his generation persisted in claiming Cobain was their voice. Regrettably he found a surefire way out. For a moment, Cobain was a Next Dylan before he became a Tragic Rock Star.

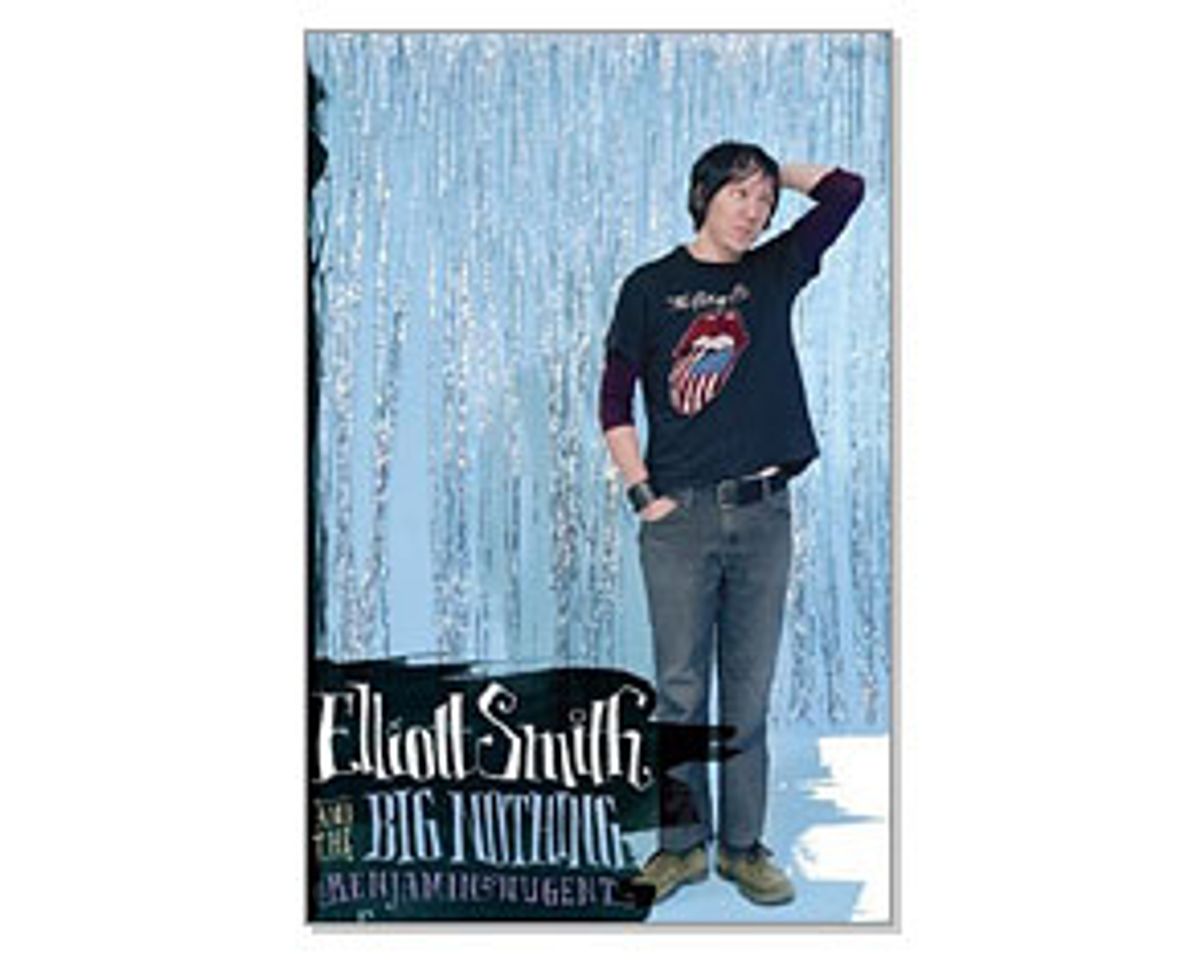

Without Cobain, legions of fans were suddenly set adrift. They could have found solace in Cobain's lesser-known kinsman Elliott Smith. Now, shortly after the first anniversary of Smith's death and the posthumous release of his final album, comes a new biography, Benjamin Nugent's "Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing." The imperative questions arise for both music geeks and earnest listeners: Was Smith a Next Dylan? Did he become a Tragic Rock Star?

In his book, Nugent quotes a friend of Smith's who notes the singer-songwriter's particular allure: "'I could never get anybody to listen to [Smith's solo debut, "Roman Candle"],'" the friend says. "'And then I figured out this really funny recipe: The time to get someone was to get them as soon as they broke up with someone ... I'd be like, 'You should listen to this,' and it'd be the same person I'd given it to six months earlier who said it was boring and sounded like Simon and Garfunkel, and they would come back to me, like, 'Your friend's amazing.'" Sad and true: Elliott Smith goes great with a breakup or losing someone you love.

Smith created compelling, layered narratives of abuse and addiction, unparalleled in their searing emotion. His songs were intimately literate and conveyed by a voice of crushing delicacy, first over flitting and intricate guitar work and later, in a bigger, fuller '60s retro rock sound. To embrace Smith after Cobain would've been easy. Not only because the hurt in his songs was so immediate, but also because Smith and Cobain lived similar lives. Both suffered through depression. Both resisted full-blown fame. Both spent a lot of time in the drizzly Pacific Northwest.

But where Cobain wailed, Smith whimpered. Cobain's ability to tap into the teenage angst zeitgeist made him a reluctant champion of the mainstream. Smith had a comparatively small pool of fans who sought him out for a fix of sadness without fury, bittersweet sorrow with a penchant for a Beatles hook.

Both fought a long, losing battle with heroin. The drug shaped the latter part of their lives and ultimately their deaths. For Smith, the drug more deeply and sometimes plainly lived in his songs. He never penned a tune titled "I Hate Myself and Want to Die," as Cobain did; instead Smith authored entire records skulking around that idea.

What most unites them now is that they both ended their lives in suicide, or at least in apparent suicide. Cobain's has been surrounded by loopy conspiracy theories and Smith's has been shrouded in genuine mystery. He died of two stab wounds to the chest with a kitchen knife, while only he and his girlfriend were present in their Los Angeles home. The death was originally ruled suicide, then deemed a possible homicide, and remains murky.

Nugent's book mentions Cobain and Nirvana but only to provide context. After Cobain's suicide in 1994, Nugent informs us, the singer-songwriter archetype all but vanished from the musical landscape. Three years later, when Smith finally achieved fame with his Academy Award-nominated song and performance of "Miss Misery" from the "Good Will Hunting" soundtrack, "he was an anomaly," Nugent writes, "a holdout for guitar rock when nobody cool was playing guitar." Nugent also notes the occasion when, upon seeing Smith perform during his earliest solo days, fellow indie-folkster Mary Lou Lord aptly proclaimed that, "'the little punk kid' on stage was 'the quintessential songwriter of our generation besides Kurt Cobain.'"

Smith was his own artist. And Nugent, who lived in the same cities as Smith and fully absorbed indie-rock culture, means to reveal Smith as the unique, beauteous talent that he was. Nugent also attempts to illuminate Smith as a person. Detailing Smith's childhood and young adult years, Nugent sheds new light on what has previously been perceived as a dark existence. Smith wasn't always haunted by a consuming depression: He liked to jam on classic rock tunes with junior high buddies; he played football even if he didn't really enjoy it (growing up around Dallas, that's what you gotta do). In Portland, Ore., he established himself firmly in the local music scene and played in the modestly successful grunge-like band Heatmiser. Most significantly, he could do one mean moonwalk. Listen to a downer like "Oh Well, Okay," and picture, if you dare, Smith gliding across the stage, à la Michael Jackson.

In interviews with friends, Nugent reveals how Smith traveled through life unable to escape a troubled and confusing childhood, in which he may have been sexually abused by his stepfather (a veiled and recurring theme throughout the Smith oeuvre). With a crippling propensity for guilt, Smith was further transformed by the hyper-p.c. atmosphere at Hampshire College and became even more self-aware in his straight, white male skin. (During this time, he also changed his first name from Steve to Elliott, because "Steve sounded too 'jockish' ... and Steven 'too bookish.'") Through this piecemeal narrative, Nugent paints a cubist portrait. The childhood abuse question remains unresolved, and we can only assume it connects with Smith's depression and substance abuse. Despite the details, Smith remains a shadowy figure and Nugent's detective work drags.

Nugent does better when he explicates Smith's songs. He identifies allusions to people and places, and points out that Smith made dark references to heroin long before he actually used the drug. The author understands the magnificently thick atmosphere of Smith's music intimately, and submerges us in it. This isn't fan worship; this work reflects real reverence and a genuine longing to understand the artist.

In his epilogue, Nugent at last makes the admission that's been obvious from the start: Smith's closest friends and family, who surface repeatedly in the text, refused Nugent access. "Dear friends of Smith's ... are absent from this book because they don't talk to the press about him and they wouldn't make an exception for me," he writes. He adds later, "I never met Portlanders Neil Gust, Joanna Bolme, Janet Weiss and Sam Coome ... who knew Smith most intimately for the longest amount of time," nor did he meet Smith's family. "If one of those four musicians or any member of Smith's family decides to talk one day," he concludes, "I bet it'll change the way people look at Elliott Smith."

It's honorable of Nugent to concede this and, in effect, recognize the shortcomings of his thorough, albeit rambling, work. Add the fact that Nugent never interviewed Smith himself while he was alive, and that too much of this book is composed of speculation and third-party clippings from fanzines and rock mags, and you begin to understand why this narrative feels helplessly distant from its subject. It's something like watching an anticipated performance from the crowded balcony of a smoky rock venue. The sound is pretty good, and every now and then a brilliant note reaches us, but mostly we're craning our necks to see past the heads blocking our view, trying to catch a glimpse of the intriguing figure onstage and sometimes just feeling bummed for being bored at what should have been a soul-stirring show.

Elliott Smith looked, for a moment, like a Next Dylan. Nugent reflects this when he captures Smith at the height of his success, the performance on the Oscar telecast. Smith, he writes, "became a symbol of something pure and rock 'n' roll and pensive ... something kids could associate themselves with, a quiet guy with a guitar floating in a sea of glitter ... he was a lighthouse in a big-nothing now, the big nothing being the glitter monstrosity of dance-floor music and frat metal claiming the charts."

Yet, as Nugent also poignantly notes, in Smith's songs "the harsh light of his scrutiny shines almost exclusively inward, onto his most personal troubles." Smith didn't lash out at or appeal to the audience in that exhilaratingly infectious manner that artists like Cobain or Lennon did. Smith was a voice to connect with, but also a sad story impenetrable to outsiders. And that's why he didn't carry the torch (or maybe the plastic cigarette lighter) after Cobain died. If he could have widened his musical and rhetorical scope, so many listeners would have flooded in. Instead, he attracted only those who could appreciate a clouded and fragile mood at arm's length.

Elliott Smith ultimately became a Tragic Rock Star. Future generations of listeners will seek him out, but in modest numbers. He would never really have cut it as a Next Dylan. He wasn't good with fame and wasn't the type to speak for a generation. As he sang on his final record, he'd rather "Burn every bridge that I cross/ To find some beautiful place to get lost."

Shares