Oliver Stone's "Alexander" is the movie of our age -- an age when immortality is a shelf at the video store. Never have a great historical hero's accomplishments seemed so inconsequential, or so damned hard to figure out. By the tender age of 25, Alexander the Great was the ruler of practically the whole world, or at least as much of it as we knew existed circa 330 B.C. As Stone shows us, after trekking with his army from his native Macedonia to grab Western Asia from Persia, Alexander went on to conquer India. Why? Because it was there. The complexity and subtlety of this Alexander doesn't stop there: At one point we see him perusing a document that's marked, in pointy-edged faux Greek letters like the ones in the old Jay Ward "Aesop & Son" cartoons, "Tax System." Because in addition to the usual fightin' and pillagin', Alexander made boundless contributions to society and culture. In "Alexander," Stone honors them with an epic squeak.

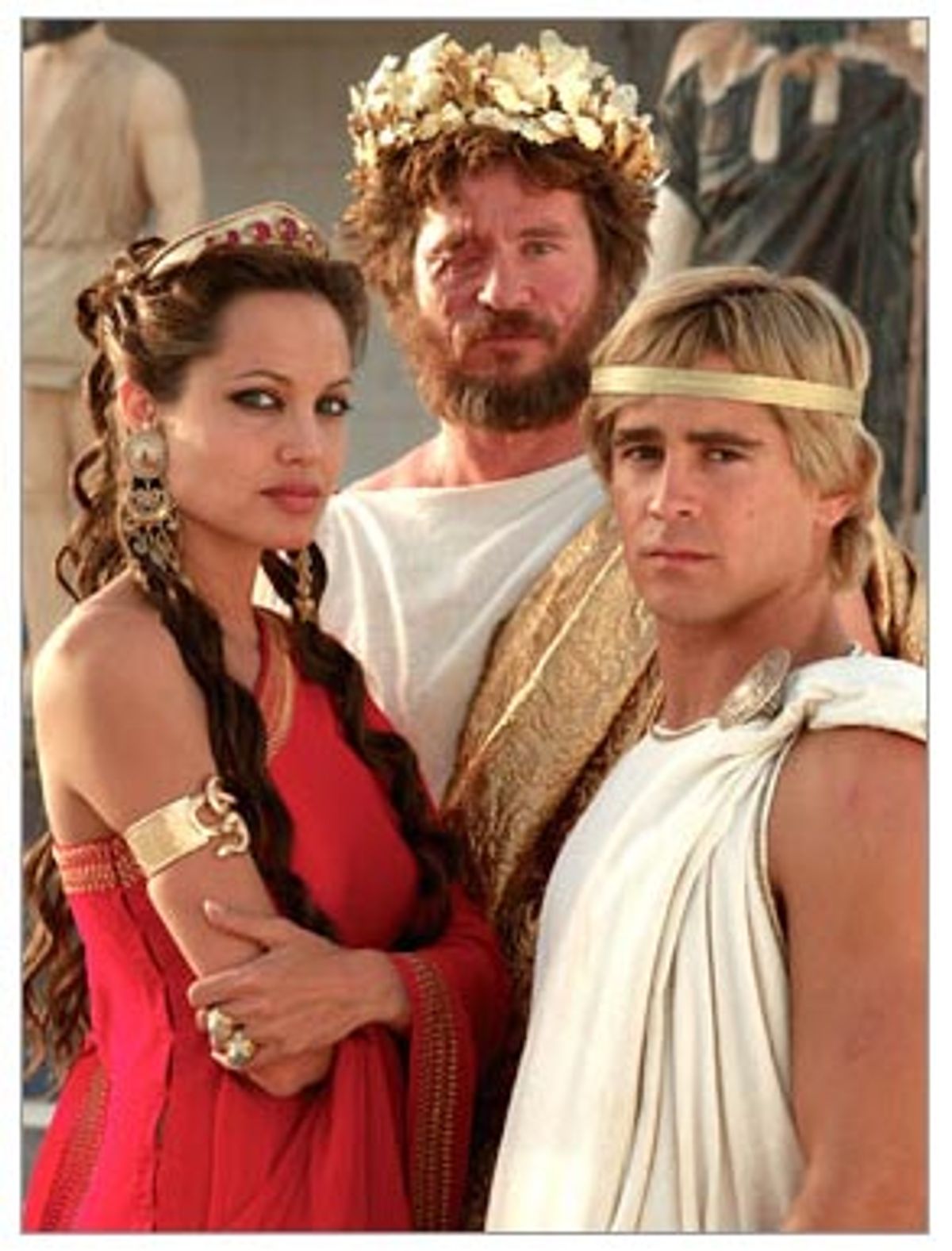

It is, however, a very long squeak -- just about three hours -- and features what used to be called, in more innocent times, an all-star cast: Anthony Hopkins shows up as old-timer Ptolemy, the handy framing device who delivers all the exposition (a necessity since without it the story would be impossible to follow); Angelina Jolie, often clad in the same type of one-shouldered Grecian gowns she favors in real life, is Alexander's mother, Olympias, a Dionysian sorceress who keeps a selection of pet snakes coiled in a basket by her bed; and Colin Farrell, in a blond dye job and dressed in an array of fetching warrior costumes, is Alexander himself, the ambitious but occasionally troubled ruler who inspires respect both in the men who serve him and in those he conquers. Lurking in there somewhere is Val Kilmer as King Philip II of Macedonia, Alexander's crusty, drunken, one-eyed ex-warrior dad, whom Olympias despises and whose bravery Alexander has inherited and will, we learn, surpass.

"Alexander" may have stars, but it's got no juice. The problem with epics these days -- among them massive clunkers like "Troy" and "King Arthur" -- isn't that they're simplistic and immature; it's that they lack Victor Mature. In striving to give us quality cinema, directors like Wolfgang Petersen, Antoine Fuqua and now Stone play everything so seriously that they never ignite our imaginations. Everything is expensive, and looks it -- filmmakers like these value costly authenticity far more than sex appeal, which is relatively cheap, although, sadly, much more rare.

Worse yet, though, "Alexander" is told in a way that's almost impossible to follow without Cliffs Notes. (The script was written by Stone, Christopher Kyle and Laeta Kalogridis.) It opens with old Ptolemy extolling the virtues of his pal Al, now long deceased, to an earnest scribe eager to take down every detail (a bare-chested hottie assists him by holding the inkwell). Ptolemy served in Alexander's army and stood by him all of his short life. When Alexander looked you in the eye, you believed you could do anything, Ptolemy asserts. "No tyrant ever gave back so much."

That's a pretty tall claim for a guy who's about to rob us of three hours of breathing time, but that's OK. It's just that the rest of "Alexander" doesn't answer any of our questions, except in the most cursory, psychology-textbook way. As Stone sees it, Alexander, whose army was never defeated in battle, continued to push East because he was fueled by ambition and weird relations with his mom (more on that later). We see his progress charted in a mosaic map made up of little beans and seeds. Europa! Egypt! Persia! The exotic names drift past us with about as much impact as the travel stickers on a vaudevillian steamer trunk. Meanwhile, Alexander dallies with good-looking boys, chief among them his closest friend, the soldier Hephaistion (Jared Leto), and takes a hot-cha tribal girl, Roxane (Rosario Dawson), as his wife. (The newlyweds have a spectacular howler of a scene in which they claw and hiss at one another on their marital bed, two animals bent on establishing dominance.)

But Alexander's life isn't all Dionysian revelry in which he wears ridiculous lion-face headdresses (although it is partly that). Exhausted after years of exploration and battles -- and the battles, with stabbed men gurgling blood and skewered horses writhing in pain, definitely take dramatic precedence over any exploration or cultural innovation -- Alexander's soldiers turn against him. He rallies them for one last fight, and this one is a doozy.

Yet, as elaborate as they are, neither of the two major battle sequences in "Alexander" resonate. They're suitably gory all right, and we do get to see Farrell on horseback, in a feathered helmet, going "Yaaaah!," his teeth tinged pink with blood. That's how it was in the old days, and yet Stone works so hard at making these battles feel so super-duper impressive that they end up seeming remote. What's far more interesting is Alexander's alleged bisexuality, which Stone is obsessed with. But he doesn't do justice to that, either. There are no graphic male sex scenes in "Alexander," but there are plenty of rummy allusions to Alexander's closeness with Hephaistion, and several scenes with boys and men frolicking and cavorting in a not particularly heterosexual way. Olympias, worried that her teenage son will fail to produce an heir, admonishes, "You're 19 and the girls are already saying you don't like them." (Could it be that he's always dragging them home to listen to his "Judy at the Acropolis" records?) And Christopher Plummer appears in a toga as Aristotle (if you close your eyes, you can hear the rounded, figgy tones of Edward Everett Horton -- shades of Jay Ward again?), explaining to his young male students that they shouldn't necessarily deny their urges: "When men lie together and virtue pass between them -- that is good." You see, in olden times, homosexuality was clean and wholesome: You don't hear Aristotle extolling the virtues of a long, slow screw from a big, dumb guy.

Stone's approach to Alexander's sexual orientation manages to be both ham-fisted and insultingly timid. It's a shame, because Farrell is at his best in his scenes with Leto. The two don't kiss, or even caress -- mostly, they just speak to each other with warm regard and lock their arms around each other in a manly clench. But Farrell is such a sensual presence (and such a hardworking actor, although as yet an untested one) that he makes the tenderness between the two men seem far more natural than the idiotic dialogue Stone and his co-writers have embroidered around it. When he looks at Leto, you see something very real inside him, a mix of romance and carnality that doesn't exactly have a name.

But Stone sabotages any depth of feeling Farrell tries to put across. In the dramatic wedding-night sequence, Hephaistion appears in Alexander's bedchamber, bearing a ring for his beloved. Dressed in a scraggly fur vest, his eyes ringed with smudgy kohl, Leto looks like a wronged hippie chick, ready at any moment to fling himself down, tearfully, on his Indian bedpread while Leonard Cohen's "Suzanne" plays over and over again on the turntable. (Leto tries hard, but trust me, no actor can survive that eyeliner.)

In an exceedingly dorky, roundabout way, the movie works hard to "explain" why Alexander is -- well, you know. His dad is domineering, demanding and withholds love. (He also likes to throw Olympias down, caveman-style, when her heaping helping of good looks become more than his one good eye can resist; she gets rid of him by vengefully pressing her thumb into it. Jolie is the only actor here who gives the movie the shot of unvarnished camp glamour it needs.) Olympias, on the other hand, adores her son. Wrapping one of her beloved snakes around the very young Alexander, still small enough to share her bed, she purrs, "Her skin is water, her tongue is fire -- she is your friend."

With a mom like that, a kid is guaranteed to grow up into one messed-up warrior, and his father's warnings ("All your life, beware of women. They're far more dangerous than men") sure don't help. No wonder the lad prefers tussling in the sun with Hephaistion.

The point Stone is crabwalking toward, maybe, is that leadership qualities are complicated, and that they can't be strictly defined by conventional notions of masculinity. But even though that impulse is admirable, Stone squelches it at every turn -- he's too conventional a director (and one with too grand a sense of his own capabilities) to ever deny his own machismo. The real Alexander may have been a complex man of many appetites. But Stone is still just a big dumb guy.

Shares