My mom served up boiled sweet potatoes, seasoned only with salt and pepper, this Thanksgiving. My boyfriend might have done the same, last year. But for our own intimate Thanksgiving dinner for two this year, Leonard expertly braised his sweet potatoes in butter, cream and sugar, yielding yams so perfect I gobbled them down with embarrassing zeal.

As Leonard gets to be a better and better cook, I find myself inviting people over to his house for dinner, and last month I finally stopped trying to convince myself that my jeans had just shrunk in the wash.

How did my engineer boyfriend learn to cook so well? Certainly not from watching the food shows the cable TV channels dish up in abundance. The personality-driven recipe files of Emeril Lagasse, Nigella Lawson, Rachael Ray, Jamie Oliver, even Jacques Pepin entertain us, but they don't teach us much cooking. And "Iron Chef"? That's just a neo-feudalistic game show that happens to involve food.

Nope, Leonard and I aren't much for food shows. It's the geeky cooking shows we devour in search of explanations, technique, equipment tests and, yes, entertainment: Food Network's gimmicky-in-a-good-way "Good Eats" (which sometimes runs as often as three times in one day) and PBS's consumer-reports show "America's Test Kitchen" (check local listings), which explain the science and engineering behind good food. Leonard got his awesome sweet potato recipe from "ATK's" "Thanksgiving III" episode, and I'm looking forward to finding out what menu items from its holiday dinner show -- as well as from "Good Eats" episodes on cookies, fudge, cake and cheesecake -- will end up on his table later this month.

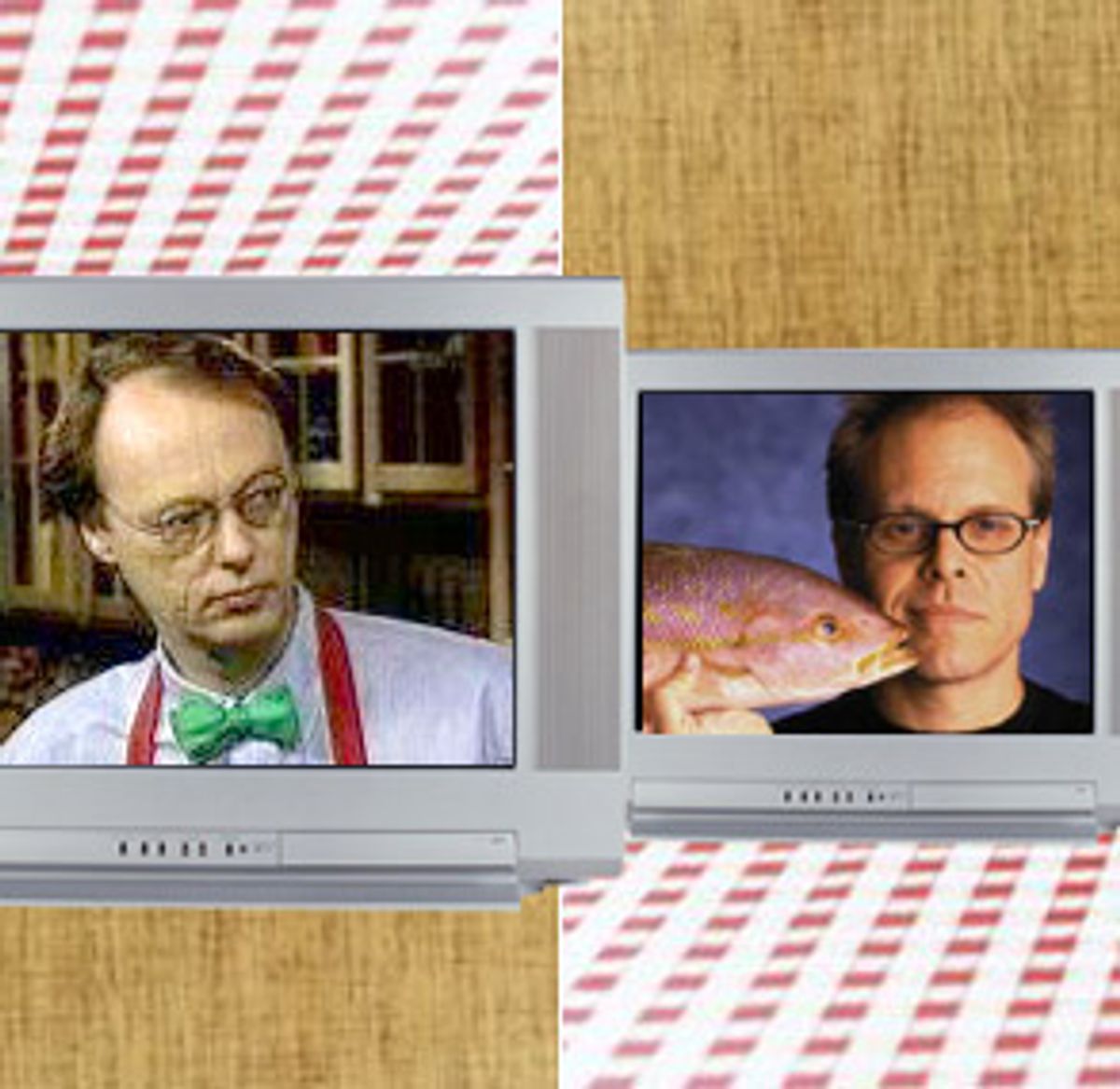

Christopher Kimball, a wry, bow tie-bedecked New Englander, hosts "America's Test Kitchen," which brings to TV some of the findings of his Cook's Illustrated magazine. Like Consumer Reports, Cook's Illustrated takes no advertising, and the heart of this show is a no-nonsense quest for the best techniques and recipes. Cooks conduct experiments to get to the tastiest version of a dish, and you're treated to descriptions of those experiments and their results instead of the standard self-indulgent cooking-show patter. "ATK" also features taste tests of store-bought products, equipment and utensil tests, and (in some episodes) a science segment where ridiculous props explain, say, browning or the effects of capsaicin.

It's worth it to read a Cook's Illustrated, even if, like me, you seldom cook. The articles read as very accessible lab reports, with hypotheses, trials and errors, and conclusions (recipes). I find them much more useful than yet another three-recipe column that begins, "While staying in a small hotel in Tuscany ..." and extols the virtues of fresh, seasonal ingredients but doesn't teach any skills or methodology.

Each episode of "America's Test Kitchen" demonstrates how to achieve a Platonic form for two or three dishes and, for contrast, offers examples of bad food (tasteless, watery soups and Jello-like custards) to avoid. But Americans as a whole don't even know the difference, according to Kimball.

"There's not a tradition here of people saying, 'You know, I just bought that chicken and it wasn't very good,'" Kimball says. "There's no tradition of that because there's no taste memory of saying, 'I grew up with a certain food and I know what it's supposed to taste like.'"

Leonard had his own "Test Kitchen" revelation last year, watching the hosts explain how to avoid something that he had never before realized was avoidable: soggy biscuits on fruit cobbler. (Don't just plop the dough atop the fruit and bake it all at once! Bake the biscuits separately.) "ATK" shines at such moments of epiphany, offering the viewer a sense that a better culinary world is possible.

"The best e-mails or notes are when people say, 'I could never cook, and I've always been a failure at cooking, and I started reading Cook's or I watch your show, and now, I actually cook and I like to cook, and the stuff's coming out,'" says Kimball. "It does give them something, confidence that they can actually do this, and they start doing more of it. That's my goal, of course. I'm insidiously trying to get everybody to go back in the kitchen."

On the other hand, "Good Eats" host Alton Brown is out to entertain more than to edify. In each episode of his show, using a variety of conceits (from morning talk show to detective story), Brown focuses on a type of food (from yellow cake to egg to barbecued pig) and explores ways to turn it into "good eats." Jokes, from subtle to slapstick, complement his focused and hyperarticulate commentary.

"My first and foremost goal is to make a half-hour of entertaining television," Brown explains. "That is the No. 1, all-time, best kind of compliment, which is that I'm making a family television show that's not boring or pablum."

But he's still teaching. Using more science than his "Test Kitchen" counterparts, Brown moves smoothly between theory and practice in every scene. Both shows throw out conventional wisdom when a cheaper, better or faster option seems obvious. Brown goes further, improvising ingredients and even equipment more often. Why buy a grill when you can make one from hardware-store parts? And at every step, we learn the chemistry and physics of the process, and thus how to vary the instructions to produce a different result. The "Test Kitchen" is a dedicated committee, but Brown is a crabby and brilliant tinker.

Brown does create unconventional dishes using the principles he's induced, inspiring his followers to do the same. (Leonard's inventions include date-fudge baklava and ice cream with strawberries and balsalmic vinegar -- both of which are much tastier than you might think.) But Brown, like the "Test Kitchen" cooks, focuses on improving familiar dishes. He says he's a "hacker, not an inventor."

"I don't have a great creative mind. I am not the guy that's going to say, 'I am going to create monkfish liver tureen with kumquat compote truffled with ...' I just don't think that way," he says. "I'm not hungry for new things. I'm hungry for good versions of things I've already had! I'm about, 'Man, let's get a better hamburger. Let's have a better slice of pizza. Let's have better bread. Better coffee.'"

Brown and Kimball seek neither novelty nor authenticity but rather aim for good food via a non-onerous recipe. If "Iron Chef" is fantasy and the pretty-chef shows are food porn, "America's Test Kitchen" and "Good Eats" are science nonfiction. Instead of an elite arena for high priests, the kitchen, as they see it, is another lab. And they make for excellent lab partners.

Shares