The big selling point, if there is one, of Mike Nichols' version of the Patrick Marber play "Closer" is seeing big-name star Julia Roberts use words like "fuck." In Nichols' world that, as well as casting Natalie Portman as a stripper, Jude Law as a shallow philanderer and Clive Owen as a horn-dog dermatologist, supposedly represents some kind of revolutionary sexual frankness, the sort of thing anyone interested in honest art should be flocking to.

But "Closer" is so bloodless that it feels like an act of arty dishonesty. Nichols and Marber seem to think they're serving up the raw goods of modern romance, but they're really just arranging its pickled innards on a pristine, chilly porcelain plate. It's a marvel of modern filmmaking in the way it so immediately renders universal human experience almost unrecognizable.

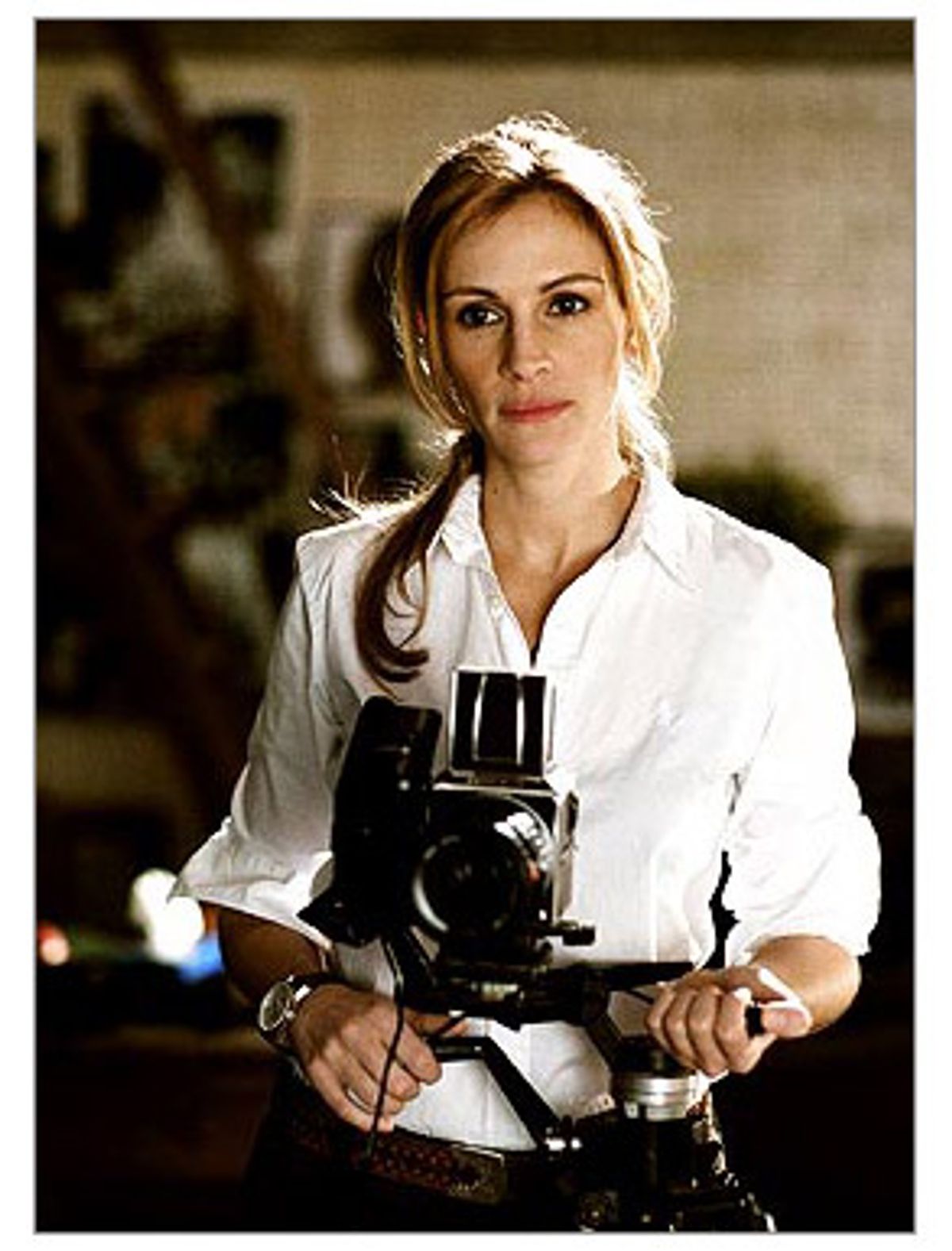

Aside from the fact that they trusted their director and the material, the myriad problems of "Closer" aren't the fault of the actors: You can see them all working hard to make something affecting, or at least engaging, from this overmasticated material. Roberts, Portman, Owen and Law play the four points of an unlikely love parallelogram: In the first scene, Law's Dan, a London obituary writer, meets Portman's Alice, an American taking a holiday from an alluded-to painful past. Fast-forward a few years: Dan and Alice have become a couple. He has written a novel and Roberts' Anna is the photographer who's taking his publicity photos. He tries to seduce her; she rebuffs him. Then, as the result of a nasty practical joke Dan plays on her, she meets and falls for (although you never see anyone in "Closer" doing anything so overtly emotional as falling) dermatologist Larry, played by Owen. That means Larry can stop frequenting sex chat rooms, as he was formerly wont to do.

The members of these two couples obsess, cheat and cross-connect, or at least just interact in a highly scripted way. None of them are allowed to have feelings that haven't been polished and minimalized into self-conscious, synthetic verbal sculptures. Love and intimacy, bitterness and resentment, loyalty and betrayal: "Closer" examines them all, with dialogue so meticulous it bears no resemblance to the way people actually talk, let alone think. "She has the moronic beauty of youth, but she's sly," Larry observes of Alice after he meets her for the first time, a playwright's semaphore, maybe, for "She's kind of cute." But Marber and Nichols both seem to have forgotten -- or, worse yet, they don't care -- that lines have to be uttered by actual actors. At best, Nichols manages to get a tepid, sub-Bogey-and-Bacall crackle (at least an Ernest Borgnine and Ethel Merman crackle) out of the interplay between his characters, as when Dan tries to weasel a kiss out of Anna, at their first meeting in her photography studio. "I don't kiss strange men," she tells him. "Neither do I," he retorts.

Nichols prunes, shapes and pares down each scene until it meets some inexplicable, exacting specification -- he's more of a topiary artiste than a director. As a piece of direction, "Closer" is a feat of stagey diligence. Nichols is a well-respected filmmaker, if not a well-loved one. Moviegoers tend to utter his name as if it were a well-known, reliable brand of laundry soap, like Tide, some kind of signifier of quality that's beyond reproach -- and then they often find themselves struggling to name more than two or three pictures, of the many he's made, that they actually like.

"Closer" may garner respect in some quarters, but it's almost willfully unlikable. Its hollowest, most calculated scene takes place in the strip club where Alice works. Larry, depressed and unshaven, watches her perform and pays for a private dance during which he paws at her and berates her, moaning about his need for human connection; she, supposedly responding with brainy banter, does the verbal equivalent of snapping gum in his face.

None of these characters is behaving particularly humanely. In fact, the movie depends on our fascination with their nastiness toward one another -- their talky self-centeredness is the only thing that gives the movie any tension. But their awfulness is written onto them in hieroglyphs, a playwright's construct -- we never sink into the skin of the characters. Instead, we're left to snigger at snip-snappety lines like the one Alice utters when she rejects Dan's offer of a tuna-fish sandwich. She doesn't eat fish because "fish pee in the sea." Dan tells her that children do too. "I don't eat children, either." The characters' personalities lie quivering, flat and dull and nearly lifeless, on the surface of Marber's dialogue.

Law and Portman give studied, strained performances here, but they do manage to throw off a few sparks of chemistry together. Neither Roberts nor Owen gives off any heat at all, but it's clear they've put a great deal of effort into thinking their way through the material. Owen (normally a marvelously muted actor) hangs onto his bruised-boxer dignity here, even if he is uncharacteristically stiff. And Roberts is so game that she sometimes comes dangerously close to making the material work. In her big confrontational scene -- giving away the specifics of it would spoil the few meager surprises "Closer" has to offer -- she rustles up the closest thing to an emotional charge any of these allegedly angry, frustrated characters can muster. (The dirty words she uses are mere trappings.) It's the only time you sense blood coursing beneath the picture's surface, but it lasts only a few minutes. The rest of the time, "Closer" feels so remote that it renders itself inconsequential. Instead of collapsing the distance between the audience and the characters, it makes that space feel a mile wide.

Shares