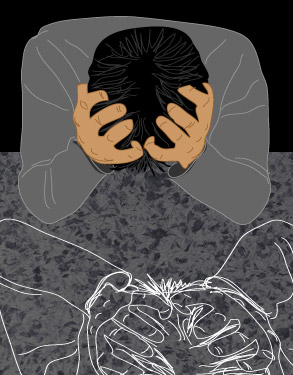

When Frannie was 35, her fiancé ended their five-year relationship. As breakups go, it was a bad one. She could hardly eat, sleep or get out of bed; she suffered panic attacks. Her friends, concerned that she was suicidal, brought her to see a psychotherapist, Belleruth Naparstek, who began treating Frannie (not her real name) with traditional “tell me what you’re feeling” talk therapy, along with Prozac. But she got nowhere. “She sat across from me like a stone, barely able to speak,” recalls Naparstek, who has a private practice in Cleveland. When she did speak, there were “long pauses that trailed off to nowhere.”

Finally, after several sessions, Frannie — now 56 and an educator in the Midwest — began to describe an earlier trauma: losing a previous fiancé, over a decade before, to a brain tumor. Naparstek thought she’d hit pay dirt. But when Frannie started to talk about this loss, she began to have panic attacks at work and episodes of both severe verbal paralysis and strange physical contortions during therapy. Speaking only, Naparstek says, “in disjointed, choppy fragments” — getting the whole story took months — Frannie finally revealed that there was yet another trauma underlying the death of the fiancé: One night after visiting him, she was brutally raped, stabbed and left for dead in the hospital parking lot. Her contortions, Naparstek realized, were a physical flashback to the rape, a phantom effort to twist away from her attacker.

Frannie had never reported the rape and never sought counseling — “I went on with my life and repressed it,” she says — until the memory got triggered in therapy. But talking about the ordeal did not bring catharsis; it made things worse. So Naparstek switched tacks. She began leading Frannie in guided meditations and encouraged her to imagine herself in a safe place, surrounded by loving and protective figures. Eventually, Frannie was able to calm herself at will, and the panic attacks began to fade away.

Frannie is one of approximately 5 million Americans who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Surprising to some is the fact that most of the people who suffer from PTSD did not fight in Fallujah, see their homes swept away by hurricanes or escape from the twin towers. (They’re not even the John Kerry people reportedly being treated for “post-election trauma.”) People like Frannie develop PTSD from more intimate or individual traumas such as car crashes, surgery, assault or even the constant sense of threat in a violent community (9 percent of Israelis are said to suffer from terror-related post-traumatic stress disorder.) In fact, more people may have PTSD today than anyone ever realized. But because of recent advances in biochemistry, brain imagery and epidemiology, researchers are finding out that all manner of conditions — some psychiatric, but some also physiological, such as chronic pain — can be traced to PTSD.

“The symptoms of post-traumatic stress can mimic severe, chronic mental illness, and many people have been misdiagnosed and assumed to be hopelessly ill,” says Naparstek, author of “Invisible Heroes: Survivors of Trauma and How They Heal.” “But people with PTSD aren’t crazy, and they get better.” Today, in fact, their prognosis is the best it has ever been. For many years, “we didn’t know how to help trauma survivors in any consistent way,” says Naparstek. As she herself discovered while treating Frannie, “Talking about it — the stock in trade of mental health professionals, pastors, good friends and spouses — is not necessarily all that helpful, and can sometimes make symptoms worse.” But now Naparstek, and more and more trauma experts, are using additional forms of treatment — such as guided imagery and somatic experiencing — that have only recently shifted from the fringe to the mainstream. Research is even underway on a PTSD pill.

While PTSD wasn’t included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1980, there are accounts of similar conditions dating to the Civil War, World War I and even to ancient times. PTSD — though now defined by a term more accurate than “Vietnam syndrome,” one of its earlier iterations — is actually not a disorder. Nor is it an illness, not even a mental one. “PSTD is a normal reaction to abnormal events,” says Beverly Donovan, a clinical psychologist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Brecksville, Ohio, who runs an intensive treatment program for combat vets with PTSD.

Here’s how trauma typically operates in the body: When you sense danger, your body automatically releases a massive blast of biochemicals, such as stress hormones (e.g., adrenaline), into your bloodstream. Then the “thinking” part of your brain asks: Am I in serious trouble, or just on a Tilt-A-Whirl? If the answer is the former, your hard-wired “fight or flight” action kicks in, sending your heart, lungs and liver into overdrive. Typically, then, you either fight or flee. All those chemicals, all that energy, gets discharged or burns off. Your parasympathetic nervous system then steps in to say “Show’s over,” decreasing blood pressure and heart rate, reactivating normal blood flow and organ function. You might be hungry or exhausted, even upset and shaken, but internally you’re fine.

But some people get stuck. Even if they know the threat has passed, their neurons get jammed on orange alert. Remaining hypersensitive, the primitive, reactive part of the brain will pull the alarm at the slightest provocation: a loud noise, a footfall, a certain smell. Meanwhile, the constant state of alert leaves a waxy buildup of biochemicals and metabolic castoffs in muscle fibers and tissue. (This is why some people’s fibromyalgia, cystitis, migraines and even irritable bowel syndrome may, at their root, be symptoms of PTSD. They may be a result of the truly unnatural amounts of both alarm-state and settling-down biochemicals that, without an efficient means of discharge, get lodged in the tissue.)

Researchers are still studying precisely why certain people are more susceptible than others to PTSD. Of two people in the same armed robbery, one may be fine while another remains traumatized. Someone who was blocks away from the World Trade Center towers on Sept. 11, 2001, may develop PTSD while someone who actually escaped a building may not. What we do know is that susceptibility to PTSD has nothing to do with, say, cowardice, or weakness of character.

So why doesn’t traditional talk therapy usually help? Therapists have found that when PTSD patients seem resistant to talking about their traumas, it’s not necessarily because they don’t want to. That’s because trauma memories are not stored where happy, or even ordinary, memories are. The sensations and experiences of trauma — terror, struggling — get packed away into the more primitive areas of the brain, to which the “rational” — speaking, thinking — parts do not have much access. The advanced areas can blab away all they want, but to the brain’s nether region, they will — at best — be as unintelligible as Charlie Brown grown-ups. Says one of Naparstek’s PTSD patients of an earlier experience with a psychoanalyst: “I kept asking my therapist, ‘What is happening to me?’ And, of course, in good psychoanalytic fashion, she asked, ‘What do you think is happening?’ Despite her good intentions, it was profoundly unhelpful.” If anything, talking — at least initially — may do the opposite of “process”; rather, it can trip the lock on a Pandora’s box. “In many psychotherapy practices this is still going on, out of sheer, well-meaning ignorance, just like mine,” says Naparstek. “Too many of us have been defeated by trying the traditional tactic first, and extending and exacerbating our clients’ suffering. It sucks.”

Based on what’s now known about how and where the residue of trauma lingers, many therapists are employing alternatives, or at least additions, to talk therapy — such as guided imagery, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, somatic experiencing and other methods — that seem to offer more direct avenues to healing by seeking out trauma where it lives: not only in the mind but also in the body.

“When exposed to trauma, some people will have trouble letting go of the experience, but not because they want to dwell on it,” says Steven Gold, Ph.D., director of the Trauma Resolution and Integration Program at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and president of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation. “There are various techniques for helping people move beyond it, which may have as much to do with the body’s reaction to the experience as with the mind’s. A few years ago some of these therapies would have been considered ‘alternative, but now the major specialists in treating trauma would consider them more mainstream.”

So how does one access the inner trauma sanctum? As it turns out, images help where words fail. In some cases, even images of the trauma: Exposure therapy, to name one now-established type of what’s called cognitive behavioral therapy, has the patient imagine the trauma repeatedly — under strictly controlled circumstances — until the concomitant reactions (panic, etc.) begin to abate. It’s more than a matter of telling yourself, “See, it’s over, I’m safe now”; it’s training the body to not go into panic mode.

Therapists may also use metaphors to soothe and dislodge trauma, to “sidestep the [verbal] booby traps that set symptoms off and create more distress,” says Naparstek. One of many image- or metaphor-based techniques is “guided imagery,” which Naparstek calls “deliberate, directed daydreaming.” It’s kind of like meditation, only with someone guiding your experience: a voice (live or recorded) suggesting that you imagine certain safe spaces or soothing sensations, each specifically designed to address a particular condition. Research has found that guided imagery can help alleviate ills including diabetes, bulimia and anxiety — and that it may be particularly helpful for trauma. Even though words are its medium, the language of guided imagery isn’t directly processed by the brain’s advanced speech and thought centers. Rather, the sensations and associations that listening to it produces — such as the presence of a benevolent, protective companion, along with reassuring voice tones and soothing music — are absorbed directly into the primitive brain: exactly where the trauma has set up shop.

Numerous other image-related therapies are gaining in respect and reputation, including eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, in which the patient is gradually desensitized to an image of personal trauma by envisioning it while also being distracted by an additional stimulus: moving the eyes back and forth, being tapped on the body or hearing tones from a headset. The Department of Defense has approved the use of EMDR as one of several therapies for treating soldiers with PTSD.

There’s also a method called somatic experiencing in which patients are not asked to “describe exactly what happened” from beginning to end but, rather, are asked to imagine — and physically mime — elements of the trauma, sometimes resulting in an imagined alternative outcome. “The body doesn’t like surprise,” says Nancy Napier, a Manhattan family and trauma therapist who uses somatic experiencing in her practice. She explains that when we’re startled by a loud noise, for example, our reflexive “orienting response” causes us instantly to look for its source. If someone comes up behind you, say, “the body gets caught in that moment of surprise,” she says. “So part of the [SE] treatment is to complete the orienting response.” Napier might, for example, have an attack victim go, inch by inch, through the motions of looking behind her, focusing on her feelings each time, only to ultimately confirm that there is no longer an attacker there. Somatic experiencing “works to bring the nervous system up-to-date so that it’s no longer locked in unresolved moments of trauma,” says Napier. Mentally and physically re-creating — and reimagining — the situation, practitioners say, is much more effective than, say, just telling yourself you’re going to be OK. It’s a matter, once again, of circumventing the verbal and accessing the physical, primitive and intuitive areas where trauma — and the means to heal it — is stored.

As for Frannie, her ultimate breakthrough came when Naparstek suggested she visit someone who works with “somatic psychotherapy” — a means of helping patients work through trauma (or other issues) via perceiving and describing internal sensations in the body. “I thought it was bullshit,” Frannie says. “Then one day I was lying on the table and [the therapist] asked me to describe my heart. And I said, ‘Well, it’s a boulder in my chest, a frozen stone, a cannonball; you can’t penetrate it.’ And I realized that that was the place where I could start working, to ‘melt’ that heart of stone.”

Sure, it’s just a metaphor, and it might even sound corny, but for Frannie, discovering the “stone” was progress. Frannie found she could describe the stone in a way that she could not describe her feelings, at least not without triggering flashbacks. It served as a stand-in for her emotions, a metaphorical repository for the effects of her experiences. “It was a way of getting to the same place that words would have brought us to had her language capacity not been so hobbled,” says Naparstek.

Over time — in Frannie’s mind’s eye — the “stone” went from hot and ugly to soft and malleable, and ultimately melted away, leaving an image of her real-live heart in its place. “My heart is back,” says Frannie, who is virtually symptom-free but for a still overprimed startle response. “I’m connected to myself now.”