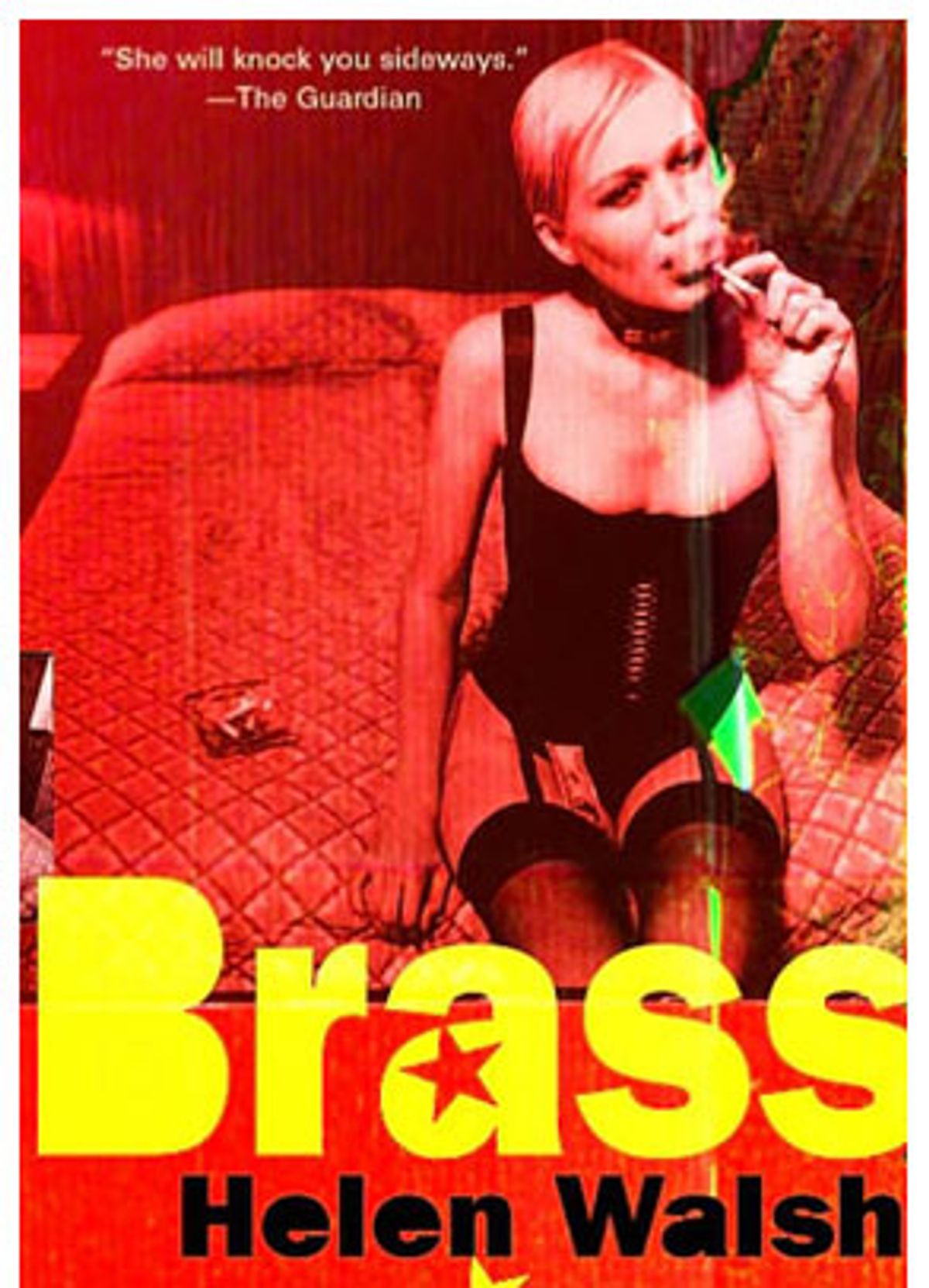

There's a particular trifecta of elements that will make not only a book but an author instantly famous: shock value, literary merit and an intriguing personal story. Helen Walsh was 26 last year when she became a star in Britain for her first novel, "Brass." A mixed-race, bisexual outsider who was socialized in the club culture of her small English town, Walsh fled to Barcelona, Spain, at 16, where she worked fixing up prostitutes and johns before moving to Liverpool, cleaning up her act and sitting down to write a novel.

Considered one of the raciest tales of British sex-and-drug culture since Irvine Welsh's "Trainspotting," "Brass" has earned Walsh a lot of hype and, because it's so well written, possible staying power as well. Recently, the (London) Observer named her one of the "prodigiously talented young people" who will define the 21st century. Now that the book has been released in the United States, it promises to make Walsh a household name on this side of the Atlantic.

"Brass" is the story of Millie, a 19-year-old Liverpudlian who devotes most of her time to dropping Ecstasy, drinking and chasing after sex -- with schoolgirls, prostitutes, a womanizing Mafia man and whoever else catches her fancy. Her lyrical voice alternates with the slangy one of her best friend, Jamie, to tell the story. Jamie is in his mid-20s and ready to settle down into marriage and domestic life; as a result, his friendship with Millie starts to deteriorate. The rift between them triggers all of Millie's self-destructive instincts as well as a bout of soul-searching, and she wanders the streets looking for redemption even as she propositions hookers and has bizarre, coke-induced encounters with strangers in bars. It is the tension between the two desires, and the two friends, that gives Walsh's narrative its particular energy.

As she's trying to understand her relationship with Jamie, Millie is also coming to terms with her absent mother, who she thinks has abandoned her. It's only by leaving her life in Liverpool to find her mother that she can, by the end of the book, make peace with herself. "Brass" is, more than anything, an exercise in watching a character come to that realization -- but it's the sex, the drugs and the gorgeously perverse street culture of Liverpool that keep it from becoming tedious. Walsh's writing veers between poetic and startlingly rough.

Critic Sarah Adams wrote in the Guardian that "Brass" is "more a bellow from the guts than a cry from the heart," and Walsh's prose is certainly a sustained bellow, both agonizing and deeply compelling. Rather than a quiet coming-of-age story, "Brass" reads like an emergency, as if to ignore it would be some sort of crime. On the first page we are told, as Millie is guiding a teenage prostitute to a cemetery for a sexual encounter, that the nearby cathedral "pierces the night like some majestic foreboding." Two pages later, the prostitute is splayed over a tombstone, and Millie reaches into her own pants to "manipulate myself hard and selfishly, the whore becoming nothing but a body. A cunt in a magazine." That such a sentiment is coming from a character who herself is a young girl is shocking, but it is the kind of shock that makes you want to keep reading.

Underneath the narrative is a dark tribute to Liverpool, the city that Millie loves but ultimately has to leave in order to redeem her life. It's also the city Walsh herself had to return to in order to write her book. Walsh talked about Liverpool with me by phone, before moving on to prostitution, pornography and why she won't read aloud the sex scenes that made her famous.

What prompted you to write "Brass"?

It was a few things, actually. The first was that I'd been in Liverpool at the time; I'd just finished university, which is actually the same university Millie goes to in the book. It's set in the heart of the red-light district, and I've always been very much in love with that area. But I was also very frustrated with Liverpool. I found it very claustrophobic and unsophisticated and crude, and the underworld there is very ingrained in everyday life. Everyone has a neighbor or an uncle who's a Tony Soprano. I wanted to move somewhere else that was sophisticated and [where] you could get nice food and the shops stayed open after 11 and that wasn't such a dangerous city, and so I moved to London.

As soon as I moved, I knew I had made a mistake. I was immediately pining for Liverpool and all the things I'd hated about it. I came back after nine months. And I remember getting off the train with all my bags and suitcases and seeing the city, and it was like seeing the city for the first time ever. It just looked so beautiful, so amazing.

I wanted to write a book that captured all those things about Liverpool. It's a very full-on, hedonistic city that really does live for the weekend. It's very consumptive, and I wanted to capture that in a character, or two characters, Millie and Jamie. Millie is very much colored by my own experience, so she was already a part of me. It wasn't a long, conscious journey of discovery. It was sudden. It literally happened when I got off the train. I had a job to go back to in Liverpool, but I gave up work, moved to my mum's and wrote the novel from the kitchen table.

"Brass" is the Scouse word [i.e., local slang] for prostitute. Yet Millie, your main character, never quite descends to that level, though she does hire a couple of hookers herself. So why the title?

It's a word that's used in a particular area of Liverpool, which is south Liverpool, which is where the novel is set. Liverpool's really split into north and south, and Millie grows up in the south, and that's where the book takes place. "Brass" is the word used by hookers themselves and also by all the people, whether it's the urchins, the drug dealers, the people who hang out in the clubs and the streets of that area. It's a word that binds all those people together. And it's also a word that's very gender specific. A woman, a normal, everyday student or a female worker, they would always use the word "prostitute." "Brass" is a male gangster term, and that's why Millie uses it. It set the theme, the kind of conceptual background for Millie's relationship with Jamie and with the street and with men. The fact that Millie uses that term says a lot about her character, about the area. But I suppose reading the book from outside the U.K. it's kind of difficult to penetrate that.

You have denied that the novel is autobiographical in other interviews, but there are a number of similarities between you and Millie -- she's a smart, young bisexual girl who's interested in sociology. She takes too many drugs, and she doesn't fit in.

My rite of passage was very similar to Millie's, though mine happened a lot younger, between the ages of 14 and 17. Millie's actually a young woman; she's 19. She's not actually bisexual -- that's something she would militate against. She never actually describes herself, though, and she doesn't subscribe to any kind of sexual-political group. She describes herself as a "sex-crazed, genderless freak." That was pretty much my understanding of sexuality when I was growing up. I never signed up to any of the camps of lesbian or bisexual -- I was always kind of free-floating, freewheeling -- and I liked the idea that you didn't have to. There were certain pockets of resistance in Liverpool and other U.K. cities where you didn't automatically have to proclaim your sexuality. If you wanted to, you could just be different people at different times. And that's the parallel between Millie and I.

At the same time that you say there's this culture of being sexually open, most of the women in the book are disgusted at the idea of having sex with Millie. Even most of the prostitutes say no.

I don't know about the rest of Europe, but in most of the U.K. cities, in the red-light districts, they're totally male dominated, and it's very shocking for a female sex worker to be approached by a woman. If women want to behave in a predatory sort of way, if they want to consume sex the way men do, that option isn't open to them really. So on the one hand you have people like Millie and other girls who are sexually adventurous and who want to go explore other things outside sex with your boyfriend, and it's just not practical. In London, there are a few lesbian pockets where they have lap-dancing clubs for women, and maybe you could hire a female escort, but it's very rare.

What made you move to Barcelona when you were 16?

I just needed to get out of my hometown, and I had also read a lot of Barcelona literature by Spanish writers, and I was entranced by the mythology of the city. Talking as we were before about European cities, Barcelona has a much more fluid approach to sexuality. Transgenderism is very big over there, and it's not in U.K. cities. My first experience of gay bars over there was transvestite bars. My mother's from Malaysia, and it's very similar to the scene that's happening over there.

You worked there as a "fixer," setting up johns with prostitutes. What did you learn from that about men and women?

It was an eye-opener. If someone had told me when I was 15 that men go on stag nights, and out of a group of heterosexual men who are all married, who are all in relationships, there's going to be a portion of them who don't want to have sex with a woman but who want to have sex with a lady-boy, I would have found that preposterous. I wouldn't have been able to get my head around it -- [you can't] until you are actually over there and you see it for yourself. I was absolutely staggered by the prevalence of that.

You didn't grow up in Liverpool, but in the nearby town of Warrington -- where, as you have said, you were an outsider for being the only mixed-race child around. Was the big city, meaning Liverpool, an idealized place for you, growing up?

From Warrington, it was a massive leap. It was the first place I'd experienced as being multicultural. As a kid, I was pretty much the only brown face in town. I didn't suffer for that. I think my brother did, but as a girl I was very lucky; men had it harder than everyone else. When I was set up in Liverpool, I was amazed by the different cultures. Yemeni, Somali, Caribbean -- living in near-perfect harmony. We had had some race riots, and it was just after that that I took my big steps into the city. But in terms of sexuality, Liverpool doesn't even have a gay scene.

I was going to ask about that. Last month Liverpool got its first gay arts festival, and there are, according to Meetup.com, at least three Liverpudlian fans of lesbian literature.

That's big!

Is this the beginning of a more sexually diverse Liverpool?

It's quite peculiar that Liverpool is a hedonistic city, and yet the commitment to music and fashion hasn't inspired a gay scene. There are gay clubs that you can go to, but there isn't so much of a scene as there is in Manchester, which is only 20 miles up the road. It's absolutely massive in Manchester. When I wanted to leave Liverpool I accused it of being crude and unsophisticated, and it is a very macho city. The men grow up with very strict male codes to adhere to -- you become a gangster, you become a footballer. It's brutal in a way. And that makes it a lot harder for young gay men to come out. Hopefully that festival will be the start of something, but I don't know. It seemed a bit hideous from what I caught of it.

You've described Liverpool as a "sexy city," which doesn't quite mesh with its reputation as a city in decline.

It had been for years. But when it was on the decline, that's when the city really was at its hedonistic peak. All the people who were on the dole and receiving benefits, it didn't stop any of them going out every weekend. They didn't have to go to work Monday morning. You'd go to parties on a Friday night and not leave the house until Tuesday or Wednesday, and all that was made possible by the unemployment crisis. People found a new religion, they found a voice, in rave culture, in acid house. The dance club Cream started in Liverpool. It's the biggest super-club, it's the biggest phenomenon to ever happen in the history of dance culture. That happened when Liverpool was at the low end. Now we have more restaurants, more art-house cinemas, more galleries, but it kind of detracts from just going out when the only choices you have are a pub or a club or to stay in. So you go out with money in your pocket, and that's all there is to spend it on, hedonism.

For one of Britain's cultural centers -- and now 2008's European Capital of Culture -- Liverpool hasn't inspired much fiction, or at least not as much as, say, Manchester.

No, it has not. I was asked recently in Holland what I had to say about the new subculture of "Mersey lit" -- in Europe, especially in Holland and Germany, they have a very romantic idea of there being a hub of Liverpool-based writers. We call the whole of Liverpool Merseyside; you know, we have the river of Mersey which runs through. I think it's taken from the Beatles and the whole music phenomenon which was called "Mersey beat." And there are some great Liverpool writers. But the thing is, we have writers who start off here, they write about Liverpool, they write from Liverpool, and then they move on. People tend to have a love-hate relationship with the city. It's all or nothing, and I'm as guilty as anyone for doing that. But it would be nice for people who make a success in the city to stay in the city. There's always that temptation to move to London or to America or somewhere bigger.

You've been most readily compared to Irvine Welsh -- did it occur to you that you were writing a female, Scouse version of "Trainspotting"?

Not at all. I was a teenager when "Trainspotting" first came out. And although it mainly dealt with the depressed heroin subculture of Edinburgh, and most of the U.K. youth population had no idea that was going on, his writing, his voice spoke to a whole generation. It was massive. Me, too. I was caught up in the magic of Uncle Irvine when I was a teenager. So it's flattering to be compared with that book. But no, I think "Brass" was very pure and honest, and I say that because I didn't have an agent, I didn't have a publisher or any expectations. I wasn't thinking what would these people think about it or what will the critics think about it. I just kind of wrote from the heart. But there were writers more than Irvine who influenced me. American writers from [Charles] Bukowski to John Fante, and even going back to Steinbeck and Hemingway and Hubert Selby in particular -- they were the writers I fell in love with as a teenager.

Most of the press on "Brass" has focused on the drugs and explicit sex, and that's understandable. The sex between Millie and women and Millie and men is raw and rough -- certainly erotic, but also pretty discomfiting. Oral sex on a tombstone, fucking a prostitute with a bottle, lubeless anal sex in the back of a car ...

I think it's impossible in 2004 -- it was 2002 when I wrote the book -- but it's impossible to write about sex from the point of view of a 19-year-old, whether it's a girl or a boy, that has been brought up in the city, any city, without bringing the pornographic into it. Millie's take on women, it's very objectifying, and it almost flirts with misogyny, but it's earthy and pornographic.

When it came to editing it, there are a whole lot of grammatical mistakes, overwriting and repetition of the same words, and my editor wanted to take those out and hone and polish it, but those were the only scenes in the book that I refused to touch, just on the grounds that I think that's how sex is. I think it's flawed and it's halting and it's earthy, certainly from the perspective of a 19-year-old university kid. That's how the sex scenes came to be. They were so easy to write, but now, when I was just in the States and had to give readings, a couple of people turned up and asked for those specific scenes, and I find it difficult now even reading them to myself. So there's just no way I could possibly read that to a room of people.

Speaking of porn, that's the thing that's shocking about Millie. She discovers her lust for women through porn magazines, which, she says, gave her the idea that "all girls are gagging for it, that they crave to be treated like filthy indefatigable whores as much as they crave to be pampered like princesses." Yet she herself is a girl.

She has a very skewed and, in a sense, morally reprehensible attitude toward sex and women. It's only through Jamie that we get a glimpse of her not getting away with it. Jamie is scathing about Millie's attitudes toward women and young girls; he doesn't agree with it. But Millie on her own -- she does have those moments the next morning of self-loathing and regret, but her sexuality again is very representative of young men's sexuality in the modern age.

Think of 13- and 14-year-old boys, 15 or 20 years ago. Their initiation into sexuality was maybe a few not-too-hardcore pornographic magazines. It was mainly behind the bike sheds and fumbling encounters with girls at school. In this day and age, you have 13- and 14-year-olds with access to the Internet, and there are such brutal and crude and dangerous perceptions of sex and women and what women want. There are a lot of boys who manage to padlock that to fantasy, but it's a bit much to ask young boys to separate completely the boundaries between fantasy and reality. It's quite dangerous, the accessibility and the pervasiveness of pornography. And Millie's sexuality has been nurtured in a way that a young boy's has. She's very much a typical predatory, animalistic male.

At the same time, there's a lot of sadness in the book. Take away the sex and pill popping and, at heart, it's a story of a young girl who is lost and sick of herself and looking for redemption from all the bad choices she has made.

When I wrote the story, that was the heart and soul of the narrative. And it was shocking to see that the first wave of press hadn't picked up on it. It was kind of overwhelmed by Millie's sexuality. But I think as the shock waves begin to settle, a lot of people have begun to pick up on that. There have been some nice reviews that haven't really mentioned the sex or the drugs. They've picked up on Millie's relationship with her mother and her father, but, more than that, on how difficult it is for a girl and a boy to negotiate a friendship.

Bad history and redemption are also part of the story of Liverpool -- which was built on the back of the slave trade -- and your own personal history.

My moment of redemption came when I first moved to Liverpool from Barcelona and decided to go to university and do something good for my mum rather than myself. In terms of what happens to Millie, I just like happy endings.

Shares